Coast Salish; Connections to the environment, involvement in conservation. With a Case Study of

First Nations involvement in the development of the

Race Rocks Marine Protected Area off Vancouver Island .

Sarah C. Fletcher, April 17, 2000

COAST SALISH AND THE ENVIRONMENT:

a) Aboriginal rights and land claims in British Columbia

b) Fisheries and Resource use

c) Coast Salish ties to the environment

d) Land Management and Ties to the Environment: The 13 moons system

e) The Bamberton Town Development Project as a model for environmental management in British Columbia

CONCLUSION:First Nations involvement in conservation and decision making:

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Among the First Nations of the North West Coast there are 13 different language families, making up 13 ‘nations’. The Coast Salish are part of the Salishan language family, forming a cultural continuum from the north end of the Strait of Georgia to the southern end of Puget Sound, covering coastal regions of British Columbia and Washington, including parts of Vancouver island. Within this large group there are a number of bands; some more closely related (linguistically) than others. Western archeologists believe that the First Nations of the North West Coast have occupied the region as of c.9000BC. The various bands argue that they have been living in that region, interacting with their environment, from time immemorial.

The Social Organization of the First Nations of the North West Coast, including the Coast Salish peoples, allowed for the combination of a clan system with a social class system. The institution of the Potlatch can be seen as being what mediated this combination. The Potlatch is a feast system found among the societies of the North West Coast based on reciprocity. Although the chief of a lineage or village organized a potlatch, it was only with the whole community working together that it could be a success. It permitted the creation of an economy that was intrinsically linked to social status, based on the concept of redistributive exchange among lineages, clans, and villages; with the lineage being the principle productive unit in the society. Although the institution of the potlatch is weaker today than it was before contact, it is still in existence. With the revival of First Nations cultural practices, the potlatch is being used to demonstrate, to the provincial and federal governments, the unity and power of various groups on the North West Coast. It is being used to support the rights of First Nations to self-determination and self-government. The potlatch system, being based on the accumulation and redistribution of surplus resources and handcrafted goods, could only have developed in a lush environment with many resources. The rich environment of the Northwest coast, including the expansive marine resources can be seen as being what permitted much of the development of North West Coast society. The various bands and nations of the area, including the Coast Salish, recognized their dependence on the environment and as such, many aspects of their lives and culture were tied to the environment. This tie to the environment still exists today and has become an important factor in land claims issues, environmental conservation, and in other attempts made by the First Nations to redefine their relationship with the state after the era of colonialism

COAST SALISH AND THE ENVIRONMENT:

The Northwest Coast is recognized as a land of abundance, a land rich in marine resources and a diversity of plant and animal species. Increasingly, it is also recognized as a landscape, which to a large extent was managed and maintained by the First Nations peoples who have lived in the region for generations…

(e.g. Turner and Peacock in Press, Anderson 1996)

a)Aboriginal Rights and Land Claims in British Columbia

In 1982 aboriginal rights were recognized and affirmed in section 35(1) of the Constitution Act. Recent court decisions have clarified the issue of aboriginal rights in BC, redefining the legal relationship between the provincial government and the First Nations in the province.

In the Delgamuukw Decision, 1993, the court of appeal held that blanket extinguishment of aboriginal rights did not occur prior to 1871 and therefore, aboriginal rights continue to exist today. Native peoples in BC never ceded their rights to land as according to the Royal Proclamation. This argument wasn’t accepted until a year ago.(Previously the government had argued that the Proclamation didn’t apply to BC as it wasn’t a British colony in 1763 when the Proclamation was accepted.) The NDP government in British Columbia has recently agreed to negotiate compensation for land claims, creating new types of relations with First Nations by giving them some rights to government, land management, and resources, as well as others.

The Van der Peet, N.T.C, and Smokehouse decisions, were all cases involving fishing restrictions which led to the evolution of tests to determine aboriginal rights.1 Aboriginal rights include the rights to engage in traditional activities (fishing, hunting etc. for sustenance, social, spiritual, and ceremonial purposes), and these may be modernized. They are rights, which are vital to the distinctive culture of aboriginal society and are dependent on patterns of historical occupancy and use of land. Included in these rights and a central motivation for First Nations involvement in conservation, is the right to teach the younger generations the cultural practices, which are intrinsically tied to the land. In order for a right to be recognized the provincial and federal courts have determined that it had to be integral to the distinctive culture of the society prior to contact. As a result, before any action occurs on crown land, the province now has to determine if there are aboriginal rights that exist in the area and if the proposed action will infringe on the rights. This policy is now in effect at all times and applies generally to all ministries and officers of the crown overseeing decisions on crown land.2

Sharma, Parnesh, Aboriginal Fishing Rights: Laws, Courts, Politics, Fernwood Publishing, Hailfax Nova Scotia, 1998.

2 Aboriginal Affairs, province of BC. Crown Land Act. And aboriginal rights Policy Framework 1999.

On December 11th 1997, the Supreme Court of Canada issued its landmark decision on the claim to aboriginal title and self government made by the hereditary chiefs of the Gitskan and Wet’suwet’en Nations.(Granting them title and aspects of self government.) This set the stage for redefining the relationship of the First Nations in BC with the state. As a result, all land claims in BC are now comprehensive; referring to land rights, resource rights and rights to cultural traditions as well as political autonomy.

b) Fisheries and Resource use

The fishing industry in Canada is a multibillion dollar business, with an estimated worth of close to $3 billion. In BC the commercial fishery sector is the fourth largest primary industry, with an estimated worth in excess of $1 billion. It is one industry in which aboriginal peoples are economically active. Many native communities along the coast are fishing communities, and with the recognition of native rights in BC they have recently become more vocal in refusing to have their rights ignored. The failure of Canadian Courts to recognize aboriginal fishing rights is a reflection of the colonialist and imperialist ideals that are still prevalent in many aspects of government.3

Fish was an integral part of aboriginal life along the coastal and inland waters of BC. Not only was it a valuable form of food, but it was also revered in song and dance, forming the economic and cultural lifeline of many bands.

“Fishing has been of such importance that it is at the very roots of our cultures; our lives have revolved around the yearly arrival of the rivers’ bounty. And so we cannot speak of fishery without talking of our cultures, because in many ways they are one and the same.”

-Gitskan-Carrier Tribal Council, in Pearse 1982:177.

Taking this into account demonstrates that the restrictions placed on First Nations fisheries had a huge impact on the traditional lifestyles of many communities. In 1990, the Sparrow decision finally recognized aboriginal fishing rights.4 During the course of the trial of Mr. Sparrow, a member of the Musqueam Indian band, (charged with fishing with a net that was too large), the British Columbia Court of Appeal found that existing aboriginal rights had not been extinguished.

3 Sharma, Parnesh Aboriginal Fishing Rights: Laws, Courts, Politics, Fernwood Publishing, Hailfax Nova Scotia, 1998.

4 Thom, Brian, Aboriginal rights and Title after Delgamuukw; an anthropological perspective, McGill Universtiy, 1998

As such it was determined that aboriginal food fishery was entitled to constitutional protection, and that protection, with the exception of conservation measures, gave aboriginal fisheries first priority over the interests of other users. This included commercial fisheries. The decision was then appealed, but was upheld in the Supreme Court of Canada. This was an important victory for native peoples in the recognition of aboriginal rights, however these rights are still limited.5 However, for a Canadian Court to declare that the economic interests of a major industry were less deserving than those of aboriginal peoples was previously unheard of. Before the Sparrow decision, aboriginal peoples had no legal rights to fish for food or for any other reason. (i.e. Ceremonial, economic etc.)

.

Although they now have these rights in theory, in practice they are still overshadowed by commercial fisheries and government bureaucracy. First Nations can now be seen as having more rights over their marine resources, however, their access to other natural resources remains restricted be government policy. In many ways, this is in direct opposition to the cultural and traditional base of the North West Coast societies, whose history and heritage have left them with strong ties to their land and to the environment.

c) Coast Salish ties to the environment

Traditionally, the various bands and tribes within the Coast Salish language group lived in a seasonal round; with large, central, permanent villages in the winter, and temporary summer campsites. For the First Nations on the Coast of British Columbia and Washington, the ocean was the central source of food extraction. In their food production nothing was wasted. Families had a wide variety of food resources. Surplus food was exchanged with affinal relations for wealth items needed in the Potlatch. Maintaining family relations was therefore of high priority, with extended family being as important as the nuclear family. The local group was also of great importance in the social organization of the Salish bands. Members of a local group didn’t have affinal or cosanguinal ties, however they do consider themselves to be the descendants of a common ancestor. Above all else, the local group served to connect the people to their land. Membership to a local group gave individuals the right to use names, (associated with status in the institution of the Potlatch) and to tell stories that connected them to their ancestors. The Salish peoples relied on their environment for survival. As such, they developed a very special relationship to their land, with their traditions and oral history linking them into the environmental and seasonal cycle of their territories.

5 Section 1 of the charter of rights and freedoms allows for the infringement of constitutionally guaranteed rights if it can be justified according to a test and section 33 allows legislative action to override charterguarantees. This allows for the limitation and control of aboriginal rights.

Transformation stories were an important way in which the Coast Salish made sense of their world and connected themselves to their environment. The stories form a conceptual bond between members of a local group.6 The Coast Salish peoples include plants, animals, rocks, and places in their reckoning of kin. This provides some insight into the cultural importance of the current political struggles over rights to resources and land. The social organization of the native societies of the North West Coast operate on the basis of reciprocity. The Salish believe that these obligations of reciprocity extend from obligations to kin and community, to the environment in which they live. This can be understood when the oral histories and transformation stories of the Coast Salish Nations are taken into account. They believe that their ancestors, spoken of in stories, were transformed into the natural features present in the environment and surrounding their ancestral villages. This aided in creating the special relationship to nature, animals, and the environment, which is still prevalent in Salishan traditions today.

6 Thom, Brian, Coast Salish Transformation Stories: Kinship, Place and Aboriginal Rights and Title in Canada, Department of Anthropology, McGill University, 1998.

Non-human ancestors, such as elements in the environment, are seen as part of the community and make up an important aspect of personal identity. Places are connected to people through kinship. They are seen as having a sense of community, history, and spiritual power. Ties to the land, as demonstrated in stories, are integral to the culture of the natives of the North West Coast. In the Sparrow case, 1990, Judge Lamer overturned the previous ruling (McCeachern) which had judged that oral histories were not permissible as evidence in land claim negotiations. As such, stories and oral histories can now be used as evidence for rights and title to land.7

Stories provide the Coast Salish peoples with the right to engage with the non-human world in various economic pursuits, tempered with the obligations and respect required, by the ancestors, towards non-human kin. From this flows the necessity for aboriginal peoples to be involved at all levels of the resource management process. The right to have a meaningful say in how natural resources are managed gives the First Nations a great deal of leverage in present negotiations.8

7 Thom, Brian, Connecting Humans to non-humans through kinship and place, draft 1997.

8 Thom, Brian Transformation stories: Kinship, Place and Aboriginal Rights and Title in Canada, Department of Anthropology, McGill University 1998.

d)Land Management and Ties to the Environment: The 13 moons system9

The 13 moons system is a strategy that was developed by the Coast Salish people for survival. It focuses on cycles, allowing the harvesting of resources at specified times and guiding the social and ceremonial aspects of life. Religion and ritual guide the movements through the seasons, while the stories associated with each moon serve as connections between religion and resource management. The system of the 13 moons makes ecology and religion inseparable.10

As an example of the 13 moons system, Sis’et the elder moon is the most important time of year ceremonially. It is a time for character building, focusing on family and interpersonal relationships. It occurs around January and is also the time of year that conservation practices are taught to younger generations. It is a time when families are gathered together, children learn how to work, taught by their elders.11 Whereas education in the Western system emphasizes individuality, the 13 moons system has a strong community focus. Each of the moons is associated with stories, certain types of weather, economic and cultural activities.

The Coast Salish bands of today believe that the social problems that many reserves are currently experiencing are because they lost control of the family institutions by losing control of their connections to the moons. The loss of the principles guiding the 13 moon system has led to dislocated culture and spiritual beliefs. As a results many elders are now trying to re-instill the values taught in the 13 moons into their communities, with the system now being taught in the elementary schools on the reserves. Children are seen as the most precious resource in Coast Salish communities. Many of the rituals and ceremonies guided by the moons reflect this.12 Respect for land is one of the over-riding principles emphasized in the system, accompanied with the idea of “taking only what is needed” creating a base for sustainable resource management.

9 See Appendix I —Seasons and the Moons

10 Paul, Philip Kevin, The re-emergence of the Sannich Indian Map, (report DFO misc.) 1995.

11Claxton, Earl, The Sannich Year, Sannich Indian school board District #63, 1993.

12 “As an example, the children of a community are the ones who carry the first salmon catch of the year up the beach. This ties together the importance of children and the environment. The children then put back the salmon bones [into the ocean] and thank the salmon, emphasizing the cycle.”- Taken from audio recording of Tom Sampson, Elder of the Brentwood First Nations speaking about the 13 moons

The Coast Salish First Nations believe in the hereditary right to land and traditions, determined by hereditary names, which are connected to their history and myths of creation. The 13 moon system guides their interaction with their environment; it stresses the importance of ancestors and leads the Coast Salish to see themselves as the youngest of all creation, as students who must learn from their environment. It also recognizes that as ‘children’, they still have a lot to learn from their environment. By looking at the 13 moon system, which links places, and the environment to ancestors and cultural traditions, the full complexity of land claims issues are brought forward. As well, the principles guiding the recent involvement of several bands of Coast Salish in marine conservation efforts are illuminated.

e)The Bamberton Town Development Project as a model for environmental management in British Columbia

“People who are dependant on local resources for their livelihood are often able to assess the true costs and benefits of development better than any evaluator coming from the outside.” -Berkes (1993)

On August 14th 1994, the South Island Development Corporation submitted a letter to the environmental assessment project office, stating their intention to seek project approval for the Bamberton Town Development Project . This included plans to redevelop the former Bamberton cement plant and surrounding privately owned lands; leading to the creation of a fully integrated new town, 32 km north of Victoria. This was the first project to fall under the auspices of the Environmental Assessment Act of British Columbia (Bill 29). The act requires that the potential impacts of proposed development projects be assessed, including the environmental, economic, social, cultural, and health effects on First Nations peoples traditionally residing in the development area. 13 It has been suggested that research on First Nations traditional land use be carried out under four frames of reference: Taxonomic (species identification), spatial (distribution of species), temporal (seasonal variation in species distribution and abundance), and social perspectives.14 The social frame of reference includes the way Indigenous peoples perceive, use, allocate, transfer, and manage their natural resources. Traditional knowledge cannot be used in isolation from the social and political structure in which it is embedded.15

The Environmental Assessment Office of BC recognizes that First-Nations will have to play a critical role in the decision making processes involving land use. They are using principles of recognition, cooperation, and respect to achieve the goal of building a more meaningful relationship with the provinces native peoples. Under the guidance of the Environmental Assessment Office a Comprehensive Heritage Impact Assessment Project was carried out on the Bamberton Town Development proposal, involving the west side of the Sannich inlet. This is the traditional territory of the Sannich, Malahat and Cowichan First Nations, all members of the Coast Salishan language group. The process included a year-long consultation between the proponent of the project (the South Island Development Corporation), the project consulting team, the Environmental Affairs Office, and the six First Nations who had interests in the area. The direct involvement of the First Nations in the management of the project was intended to provide a management plan for the future protection and preservation of the First Nations cultural, spiritual, and ceremonial interests associated with the Bamberton lands and surrounding area.

13 Aboriginal Affairs, Province of British Columbia, Crown Land: Activities and Aboriginal rights, 1998. (gov. doc.)

14Taken from the Report of the First Nations Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment and Consultation; Component- Bamberton Town development project- First Nations Cultural Heritage Study.

15Johannes (1993:35) Bamberton Town Development Advisory Committee

The First Nations management committee involved in the project was composed of elected chief councilors of the six local First Nations with primary interests in the area. These included the Malahat, Tsartlip, Pauquachin, Tseycum, and Tsawout bands, as well as the Cowichan tribes. The management committee structure that evolved was the first to provide a meaningful process for direct First Nations involvement in the co-management of a project that had the potential to affect their lands. The process of the study also provided a means of communication between all interest groups. The meetings of the management committee were open to all interested members of the First Nation communities, and as such, they provided an open forum for discussion of all the issues and concerns involved.

Many aspects were included in the First Nations cultural heritage study in the Bamberton Town Development assessment. There was a compilation of the aboriginal use of the area (based on documentary and oral research), traditional use areas inventory, archeological resources inventory, ethno-botanical surveys, and an examination of spiritual, sacred, and culturally sensitive areas.16 It also looked at the socio-economic components and the economic opportunities that could potentially be derived from the project. After outlining the traditional and contemporary uses of the land surrounding the proposed development, the report looked at the importance of these activities to indigenous peoples today and their perceptions and concerns relating to the potential loss of these should the proposed Bamberton Development proceed. 17

16 Report on the First nations Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment and Consultation: Component Bamberton Town Development Project- Introduction and Background, Environmental Assesment Office

17Taken from the report on the First Nations Cultural Heritage Impact assessment and consultation, Results part I: the First Nations context, Environmental Assessment Office, British Columbia.

The Bamberton analysis used the 13 moons system as a reference, recognizing that the spiritual and economic aspects of the environment are not separated for First Nations peoples. In this way they also recognized the connection between religion and resource management. The use of the religious system’s emotional power and intellectual authority in promoting the conservation of resources and teaching environmental knowledge was emphasized by the First Nations involved in the study.

The Bamberton Town Development study has been hailed as a model for how the planning of major land development projects can proceed with the meaningful participation of interested First Nations. It could act as a precursor for greater First Nations involvement in regional land use planning.

CONCLUSION: First Nations involvement in conservation and decision making:

“The People of the Salish Sea recognize the close relationship between land and sea. They have witnessed first hand the impacts of development on marine resources in the Strait of Georgia and Juan de Fuca. These impacts have altered traditional life.” – Tom Sampson, Elder of the Brentwood First Nations

On September 1st, 1998, The Honourable David Anderson, the minister of Fisheries and Oceans in British Columbia at the time, gave a landmark speech announcing the creation of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). 18 In the plans of an MPA the necessity of getting First Nations involved in Marine conservation and resource management was stressed. The concept of Marine Protected Areas arose from the development of an Oceans Strategy based on the principles of the Oceans Act (1997). These included ideas of integrated management, sustainable development and an ecosystem based precautionary approach. Above all, The Oceans Sector was assigned to develop this strategy with the collaboration of federal agencies and other levels of government, including First Nations.

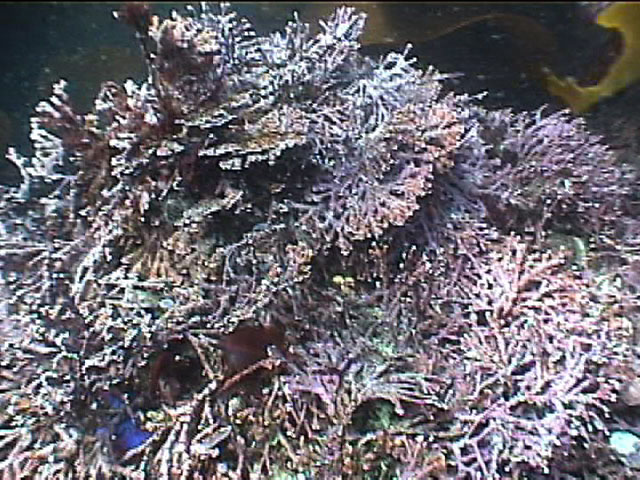

The mandate of the Marine Protected Areas includes the protection of fisheries resources, endangered species and habitats, unique habitats, and marine areas of high biodiversity. 19 The Honourable David Anderson announced that the site of one of the two pilot MPAs was going to be Race Rocks, an area that had previously been an ecological reserve, established in 1980 by the provincial government.20 It is an island off the extreme southern tip of Vancouver Island, 11 nautical miles from Victoria. As a pilot Marine Protected Area Race Rocks is providing the opportunity to learn and test different applications of MPA assessment, legal designation, and management as well as addressing the concerns of local First Nations, (namely Coast Salish bands).

Race Rocks has been an important part of Coast Salish First Nations for generations. The area is known in the Klallum language as ![]() , meaning ‘swift waters’. According to Anderson, the cultural values of the First Nations are consistent with the values behind MPAs. Their establishment will not affect First Nations opportunities to fish for food, social, or ceremonial purposes, and the development of Marine Protected Areas is consistent with the long term direction of future treaties between the First Nations and the two levels of government in BC. First Nations will be fully involved in the development of an effective decision making process for Marine Protected Areas in Canada.21

, meaning ‘swift waters’. According to Anderson, the cultural values of the First Nations are consistent with the values behind MPAs. Their establishment will not affect First Nations opportunities to fish for food, social, or ceremonial purposes, and the development of Marine Protected Areas is consistent with the long term direction of future treaties between the First Nations and the two levels of government in BC. First Nations will be fully involved in the development of an effective decision making process for Marine Protected Areas in Canada.21

Lester B Pearson College, an international school that was involved in the creation of the Race Rocks ecological reserve, is also involved in the stewardship of the new Marine Protected Area. Pearson College carries out a schools program on the island for local elementary school groups. In the past, this has focused largely on aspects of marine biology, and environmental conservation. The program is now also being used to introduce students to the role of marine coastal ecosystems in the culture of First Nations, including ceremonial interaction with the ecosystem as well as traditional sources of food. In this way they are hoping to ensure the sustainability of resources by enabling students to recognize their role in the stewardship of marine resources.

The hallmark of the Marine Protected Areas are that they require the cooperation of many different groups. The process of setting up the pilot MPA has been a collaborative effort, involving Becher Bay First Nations, Pearson College, Navy representatives, environmental groups, Fisheries and Oceans, BC Parks, and the Ministry of Environment. Representatives from the Beecher Bay and the T’Souke Coast Salish groups are being consulted in order to determine traditional uses of the area and to ensure regular communication on ecological reserve management issues. It is one of the first projects to attempt this type of collaboration.

18Anderson (1996)

19www. racerocks.com – MPA

20See Appendix II- Speech by David Anderson

21Statement by David Anderson, Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, September 1st 1998.

The involvement of the First Nations in the creation of the ![]() MPA has led to the adoption of many of the principles found in the 13 moon system into the management plan. Much of the information from the traditional land use study of the Bamberton Town Development project is also being used as it was the first thorough documentation of the traditional uses of plants and wildlife in the area. The Bamberton project is seen as a model for the future involvement of First Nations in decision making and management processes.

MPA has led to the adoption of many of the principles found in the 13 moon system into the management plan. Much of the information from the traditional land use study of the Bamberton Town Development project is also being used as it was the first thorough documentation of the traditional uses of plants and wildlife in the area. The Bamberton project is seen as a model for the future involvement of First Nations in decision making and management processes.

On March 9th 2000, the Beecher Bay First Nations held a traditional burning ceremony near ![]() . Its intention was to bring together all the parties working on the project; to provide an opportunity for the non-natives involved to gain and idea of the respect that First Nations have for land resources and ancestors. It was open to all members of the Race Rocks Advisory Board. (those involved in setting up the pilot MPA) As well as representatives from the Federal Fisheries Department, Environment Canada, the Department of National Defense and a group of students and faculty from the nearby Lester B. Pearson College. Members of First Nations from Sooke, Esquimalt, Songhees, and Beecher Bay were present as well as several Coast Salish from the United States. During the ceremony young people served as ‘servers’; it was their role to show respect to the ancestors. Under the direction of the elders present 100 plates of food were burned. (Including salmon, bannock, desserts, juice etc.) According to observers the smoke went straight up, and then down and over the observers, a good sign, reflecting the support of the ancestors. Whenever major decisions are being made it is necessary, in Coast Salish culture, to ask for the advice and approval of the ancestors. This was needed before the creation of the Marine Protected area could proceed and was fulfilled by the burning ceremony. The importance and the need for the ceremony was explained by Tom Sampson:

. Its intention was to bring together all the parties working on the project; to provide an opportunity for the non-natives involved to gain and idea of the respect that First Nations have for land resources and ancestors. It was open to all members of the Race Rocks Advisory Board. (those involved in setting up the pilot MPA) As well as representatives from the Federal Fisheries Department, Environment Canada, the Department of National Defense and a group of students and faculty from the nearby Lester B. Pearson College. Members of First Nations from Sooke, Esquimalt, Songhees, and Beecher Bay were present as well as several Coast Salish from the United States. During the ceremony young people served as ‘servers’; it was their role to show respect to the ancestors. Under the direction of the elders present 100 plates of food were burned. (Including salmon, bannock, desserts, juice etc.) According to observers the smoke went straight up, and then down and over the observers, a good sign, reflecting the support of the ancestors. Whenever major decisions are being made it is necessary, in Coast Salish culture, to ask for the advice and approval of the ancestors. This was needed before the creation of the Marine Protected area could proceed and was fulfilled by the burning ceremony. The importance and the need for the ceremony was explained by Tom Sampson:

” Before we can talk and make decisions about this Marine Protected Area Proposal, we must get to know each other on our terms.”-Tom Sampson, Elder of the Brentwood First Nations

As a result of the recent Delgamuukw decision, the relationship between the First Nations in British Columbia, the provincial and federal governments and the general public is in the process of changing. This change will also alter the role of First Nations in decision making processes as they gain more autonomy and work towards their goal of self determination. The ![]() Marine Protected Area initiative goes beyond Race Rocks and those directly associated with it. First Nations in BC are looking to

Marine Protected Area initiative goes beyond Race Rocks and those directly associated with it. First Nations in BC are looking to ![]() (previously Race Rocks ecological reserve) as a model of what role First Nations will play in future processes and interactions with senior levels of government in Canada. As such , the creation of Marine Protected Areas ties together the past and the present. It reflects many of the traditional values of the Coast Salish and their connections to the environment, while leading to the formation of a possible model for First Nations involvement in Canadian politics and decision making in the future.

(previously Race Rocks ecological reserve) as a model of what role First Nations will play in future processes and interactions with senior levels of government in Canada. As such , the creation of Marine Protected Areas ties together the past and the present. It reflects many of the traditional values of the Coast Salish and their connections to the environment, while leading to the formation of a possible model for First Nations involvement in Canadian politics and decision making in the future.

Bierwert, Crisca, Brushed by Cedar, Living by the river, Coast Salish figures of Power, University of Arizona Press, Tuscon, 1999.

Calxton, Earl, The Sannich Year, Sannich Indian School Board, District #63, Victoria, BC, 1993

Coates, Ken S. Summary Report: Social and Economic impacts of aboriginal land claim settlements: A case study analysis, Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs, 1995.

Fletcher, Garry L., The First Nations People and Race Rocks, Race Rocks Ecological Overview, Lester B. Pearson College, Victoria, 1999.

Heaman, Isabel, Summary of Delgamuukw. http://members.tripod.com/arcbc/delgamuu.htm

Paul, Philip Kevin, The Care-Takers: The re-emergence of the Sannich Indian Map, Report DFO-Misc- 1995.

Sharma, Parnesh, Aboriginal Fishing Rights, Laws Courts and Politics, Fernwood Publishing, Halifax, 1998.

Thom, Brian, Coast Salish Transformation Stories, Kinship Place and Aboriginal Rights and Title in Canada, Dept. of Anthropology, McGill University, 1998.

Thom, Brian, Connecting Humans to non-humans through kinship and place; draft 1997.

Thom, Brian, Concepts in Landuse, Stolo curriculum, 1995.

Thom, Brian, Co-management, Negotiation and Litigation: Questions of power in traditional use studies, McGill University, 1997.

Thom, Brian, Aboriginal rights and title in Canada after Delgamuukw, anthropological perspectives, McGill University, Jan. 1999.

- http://a100.gov.bc.ca/appsdata/epic/html/deploy/epic_document_129_15398.html

Report on the First Nations Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment and Consultation; Component: The Bamberton town Development Project- Introduction and Background, sec.1.0, government perspective, Environmental Assessment office of BC, 1997.

- Public Consultation Begins on Review of Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, Assembly of First Nations, Dec. 14th 1999.

- http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/admin/govtpages/davidanderson.htm

Statement by David Anderson, Minister of Fisheries and Oceans- Marine Protected Areas, Victoria, BC, September 1998. - http://www.racerocks.ca

Race Rocks Marine Protected Area home page. ed. Garry Fletcher, Lester B. Pearson College - https://www.racerocks.ca/first-nations/ Garry Fletcher, Lester B. Pearson College

- : Brian Thom’s Coast Salish Home Page

- -audio tape of Tom Sampson, discussing the 13 moons system.

A term paper by Sarah C. Fletcher, April 17, 2000presented as part of the coursework for :Anthropology 151-338B : Professor Lambert- McGill University , Montreal, Quebec, Canada