Background:

The automation and the de-staffing of the former Coast Guard-Operated Light Station on Great Race Rocks happened in 1997. This would normally have left the island without a generator, as all buildings and equipment were to be removed when the automated foghorn and the light were installed, there was theoretically no need for a generating station.

The automation and the de-staffing of the former Coast Guard-Operated Light Station on Great Race Rocks happened in 1997. This would normally have left the island without a generator, as all buildings and equipment were to be removed when the automated foghorn and the light were installed, there was theoretically no need for a generating station.

Lester Pearson College decided to hire the former keepers, Mike and Carol Slater, to stay on at the island as ecological reserve guardians. Since that time the Coastguard has cooperated to keep the equipment updated.

Two new double walled tanks that meet environmental standards were constructed next to the engine room on the island. Fortunately, the need for oil on the island will be reduced in the future when more Sustainable Energy Systems are developed.

Since the Coast Guard lease from the Provincial Environment and Lands Department was changed to reflect the decreasing envelope of use by the Coast Guard, the rest of the Island was then returned to the Province, and plans were made to include that as part of the Ecological Reserve. An agreement was made with Coast Guard and Provincial Environment officials as to what would constitute site remediation for the island.

This image shows the 7 old fuel tanks used for energy. They were single walled tanks and they could have contributed to an oil spill in that sensitive environment. The concrete pool around the cradles was built to contain any leaks or spills

This image shows the 7 old fuel tanks used for energy. They were single walled tanks and they could have contributed to an oil spill in that sensitive environment. The concrete pool around the cradles was built to contain any leaks or spills

In the spring of 2000, they had planned to remove the concrete base for the oil drums as well, but it was considered that it may prove too much of an environmental impact given that the pigeon guillemots, sea gulls and black oystercatchers were establishing nesting territories .They agreed to put it off until a time in the year of minimal impact. It was decided that January and February would be ideal. By May of 2001, the Canadian Coast Guard removed the set of 7 fuel old oil tanks from Great Race Rocks. These tanks had been installed in the 1970’s when the environmental regulations regarding such installations were not as stringent as they are today.

In the spring of 2000, they had planned to remove the concrete base for the oil drums as well, but it was considered that it may prove too much of an environmental impact given that the pigeon guillemots, sea gulls and black oystercatchers were establishing nesting territories .They agreed to put it off until a time in the year of minimal impact. It was decided that January and February would be ideal. By May of 2001, the Canadian Coast Guard removed the set of 7 fuel old oil tanks from Great Race Rocks. These tanks had been installed in the 1970’s when the environmental regulations regarding such installations were not as stringent as they are today.

On January 16, 2001 the coast guard delivered by helicopter the equipment necessary for removal of the concrete tank farm retaining berm.

On January 16, 2001 the coast guard delivered by helicopter the equipment necessary for removal of the concrete tank farm retaining berm.

By mid- February, a large pile of concrete rubble was all that was left of the cradle.

. The concrete had been neatly pealed from the original rocks underneath and it was now ready for the next stage.. Removal by helicopter.

By the end of April 2001, the Coast Guard had completed the removal of all the concrete rubble by helicopter and the outcrop is restored to bare rock again.

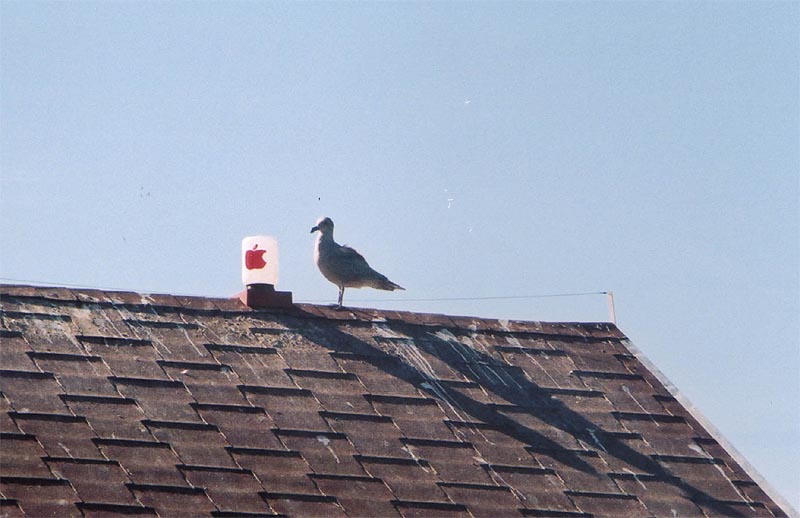

We have attempted to keep out invasive plant species and have planted seeds from native grasses in the small crevices of the rock. The seagulls responded to this new extension of territory and within two years took it over as a nest site

We have attempted to keep out invasive plant species and have planted seeds from native grasses in the small crevices of the rock. The seagulls responded to this new extension of territory and within two years took it over as a nest site

These pictures were taken in February, 2005. From the tower, the area which contained the tank farm, is no longer distinguishable.

The rock outcrops have been recolonized by native plants.

We also watch for excessive growth of introduced invasive species, and selectively remove them by hand