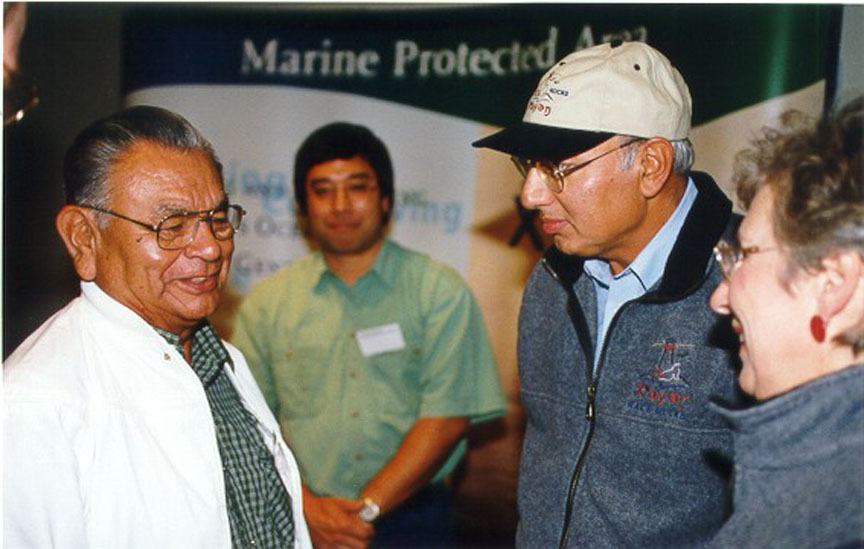

We were fortunate to have Tom Sampson on the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area Advisory Board in 2000-2002. Tom brought to the board a welcome First Nations perspective . His concept of the three-legged milk-stool model of governance for the MPA was whole-heartedly accepted by the advisory group and formed our basis for recommedation to DFO for MPA status.

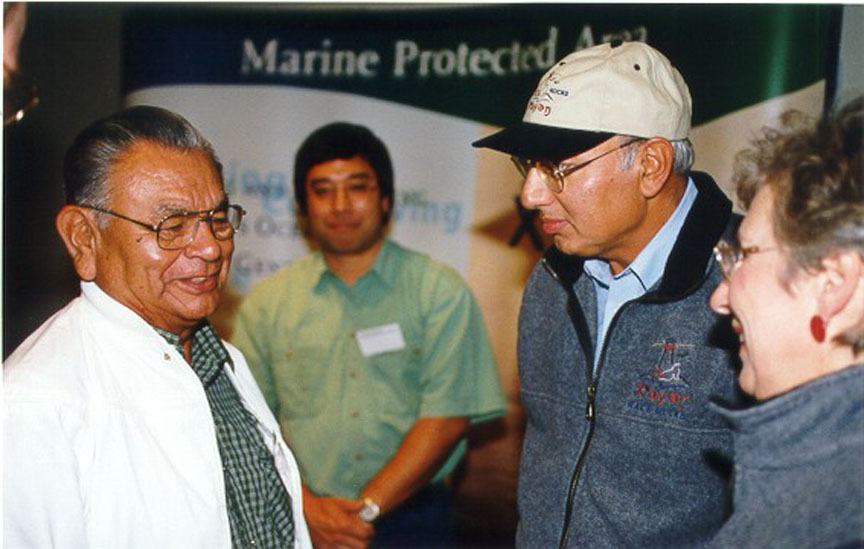

Tom Sampson on the left conversing with Federal Fisheries Minister, Herb Dahliwal and Provincial Environment Minister Joan Sawiki at Lester Pearson College on the occasion of the formal announcement of the creation of the Race Rocks MPA .

In his model, where the Provincial,Federal and First Nations governments formed the legs of the stool which supported the seat which was composed of the stake-holders and the marine ecosystems of the area . Unfortunately when the proposal went to Ottawa this model was not accepted, leading to a breakdown of the MPA process.

The article below appeared in a Georgia Strait Alliance newsletter:

Outgoing GSA (Georgia Strait Alliance) director Tom Sampson has lived all his life on the shores of Saanich Inlet. His family’s tradition is that the first born always goes to the grandparents—a way of ensuring that the new generation gets a solid grounding in traditional knowledge. As the eldest of 12 children, Tom was raised by his great grandmother, a remarkable Halalt woman who had raised his father before him.

He describes her as “the lady who taught me everything”. In her 80’s when two-year-old Tom came to live with her, she taught him history, his place in the world, spiritual beliefs and all about the natural world, in both languages of the Coast Salish, her own Halkomelem (Cowichan) and her husband’s Sencoten (Saanich). No one knew her exact age, but baptismal records showed she was over 120 when she died about 30 years ago.

Tom became immersed in the English language when he started school. Fortunately his great grandmother refused to let the church take him away to residential school, though five of his siblings weren’t so lucky. Tom did well at Indian Day School, and qualified for an academic program at St. Louis College in Victoria, where he attended grades 10 and 11. He enjoyed school and excelled in math and languages, learning to speak French and Latin on top of his other three languages. But it was a hard time for his family economically, so he quit and went to work in the woods as a whistle-punk.

It was a time of rapid change and development of resource industries. Yet already the problems were starting to show, if one paid attention: the trees being cut were significantly smaller than those Tom’s father had cut during his time as a logger.

Tom describes the devastation of resources that he has seen over his 64 years and how this has led to “a crisis all across North America”. He remembers, as a young man, regularly building fires on the beach to steam clams and mussels. Today, he says, that’s not possible, “because our beaches have been destroyed”.

“We seem to have the attitude,” he says, “that we need to destroy what doesn’t pay off monetary value of some kind—that it has no value and should be terminated. Scientists, managers and technicians seem to believe they know more about the environment than our people.”

He describes predictions that his people have made for decades about salmon, herring and other resources —that unless these were managed in a different way they would disappear. He quotes Chief Seattle and other tribal leaders over the past 50 years, but says they were always ignored by government officials. “We don’t have the degrees and diplomas, so our information isn’t considered important,” he says. “Yet our total survival has been based on understanding nature.”

“Our concept of harvesting of the land and ocean are based on the 13 moons of the year—the absolute time clock of nature, ” he explains. “We managed our resources by understanding this clock, which meant there was a right time for everything, and a time we weren’t allowed to harvest.” Tom has organized sessions on the 13-moon concept as part of his work on the Race Rocks marine protected area, where he has worked to improve cross-cultural understanding and appreciation for the traditional knowledge his people bring to the table. “It’s important that people understand that when we talk about the land we’re talking about a relationship that goes back thousands of years,” he says. “We know this land better than anybody else.”

This focus on cross-cultural awareness has been evident in other environmental work that Tom has tackled. A few years ago he played a key role in getting the BC Environmental Assessment Office to undertake a ground-breaking Aboriginal Land Uses Study within the Bamberton Environmental Assessment, which documented traditional knowledge from elders and others from the Saanich tribes; it was done in the traditional language and then translated into English.

Tom believes that listening is the key to understanding the environment. He remembers his great grandmother telling him to go down to the beach and listen to the ocean, because “if you don’t listen to it and hear the stories, you won’t learn”. Listening to each other is just as important to Tom, and he believes this skill is not being taught to most young people today.

Tom has taken a leadership role for most of his adult life. He’s been involved in tribal politics right to the national level, serving as Chief of Tsartlip for 24 years, chairman of the South Island Tribal Council for 22 years, vice-chief of the BC Assembly of First Nations, chairman of the Assembly’s Constitutional Working Group for Status Indians and chair of the Douglas Treaty Council.

Although “retired” from tribal politics, Tom has certainly not slowed down. The schedule of long days that he keeps as a volunteer would exhaust most people half his age. He works tirelessly, helping people that the system has failed.

One of his key concerns is how the justice system has been unfair to aboriginal people and ignored their beliefs about individual and community healing. “The system works if you can afford it,” he says, pointing out that from 60 to 90% of his people live in poverty. It is this poverty that has motivated Tom to work for his people.

Another area of his volunteer work is community health. He’s working more with older people these days, since the average age of his people has risen (though it’s still only 55). But he says his tribe has to struggle against the legacy of the 40-year-long residential school experience, which destroyed the social fabric of many families, removing positive family models and leading to many of the social problems experienced by native communities today.

But there’s been no shortage of strong models in Tom’s family. He remembers his mother, a Nez Perce from Idaho, serving on the Tsartlip council at “a strange time” when the band elected an all-woman council (one of the first in his territory) with a man as chief.

Tom’s wife of 43 years, Audrey—as active as Tom in community work and a vocal advocate of aboriginal rights—also comes from a family of strong models. Her father was a Cowichan chief and tribal spokesman for many years, and like Tom, her mother served on the band council. Audrey has served on the Tsartlip council, and now works as coordinator for adult health care for all the Saanich First Nations. Tom is visibly proud of Audrey and impressed with her ability to juggle her roles as mother, grandmother, great grandmother, housewife and full-time health administrator.

But he’s no slacker himself! On top of his community-based work, these days he’s very busy building the new Coast Salish Sea Council, an initiative he launched to bring together the close to 90 Coast Salish tribes on both sides of the Canada-US border, to develop agreements and move forward on social and environmental issues. Later this month the Lummi tribe will host the first major meeting of the Council, and Tom is busy organizing this.

He’s also doing a lot of traveling—recently to Seattle, Ottawa, and Texas, speaking out on environmental issues and urging that action accompany agreements.

When he gets time at home he loves to garden, a skill he learned from his father who taught him that, “when you run out of money at least you’ll have food”. This year he has planted a full acre with flowers and vegetables. He also spends as much time as possible with his five children, 10 grandchildren and one great grandchild, who all live close by. He thanks his great grandmother for teaching him the importance of “never losing” his family.

Tom says he has learned a lot from his first year with GSA and he plans to stay involved even though he will no longer be on the Board. One thing that’s made a big difference is learning to use a computer (something he had to do over the past year as a Director). Being “wired” has provided him with daily information from all over the world, which Tom says has “helped me understand issues, linkages and the reasons behind things.” He sees modern communication skills as vital for young people.

But spiritual beliefs form the heart of his environmental philosophy. “Conservation and management of resources are inseparable from these,” he says. “If you don’t see the spiritual need for the land and water, then people will continue to dump raw sewage, log mountains, and devastate the streams beyond repair. We have to look at ourselves. We can’t be holistic without a spiritual connection to the land.”

SOURCE: Georgia Strait Alliance Newsletter

The Race Rocks taxonomy is a collaborative venture originally started with the Biology and Environmental Systems students of Lester Pearson College UWC. It now also has contributions added by Faculty, Staff, Volunteers and Observers on the remote control webcams.

The Race Rocks taxonomy is a collaborative venture originally started with the Biology and Environmental Systems students of Lester Pearson College UWC. It now also has contributions added by Faculty, Staff, Volunteers and Observers on the remote control webcams.