A slide show by Ron Bellamy of Sooke August 2018

Author Archives: Garry Fletcher

Federal Government Report on Healthy Oceans

Committee report No. 14- FOPO (42-1) House of Commons

HEALTHY OCEANS, VIBRANT COASTAL COMMUNITIES: STRENGTHENING THE OCEANS ACT MARINE PROTECTED AREAS’ ESTABLISHMENT PROCESS — Report of the Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans … Bernadette Jordan Chair

Ed note: After two unsuccessful attempts to finalize the MPA designation for Race Rocks, I find it interesting to see this committee report so I have included the table of contents here , to see the complete document see this PDF FILE: included in the report are 25 recommendations.(.foporp14-e)

Link to the work done by the Race Rocks MPA advisory Board in two rounds of meetings– 1998-2010

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF MEMBERS

CONSERVATION OF MARINE BIODIVERSITY

C. Protected Areas: Definitions and Guidelines

D. Oceans Act Marine Protected Areas

CURRENT CRITERIA AND PROCESS USED TO IDENTIFY AND ESTABLISH OCEANS ACT MARINE PROTECTED AREAS

B. Science-Based Decision-Making

1. Selecting Areas of Interest

2. Community-driven Protection

3. Establishing a Marine Protected Area

C. Transparency With Regard to Consultations

1. Indigenous Rights and Interests

E. Plan to Achieve Canada’s Marine Conservation Targets

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF MARINE PROTECTED AREAS

A. A Precautionary Ocean Management Tool

B. Maximizing Marine Biodiversity Benefits

SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF MARINE PROTECTED AREAS

A. Impacts on the Fishing Industry

2. Concentrating Fishing Efforts

B. Impacts on Subsistence Harvesting by Indigenous Peoples

C. Impacts on the Shipping Industry

ENHANCING THE OCEANS ACT MARINE PROTECTED AREAS’ ESTABLISHMENT PROCESS

A. Transparency: Ensuring a Comprehensive Consultation Process

2. Consultation Inclusiveness and Sharing of Information

2.2 Providing Relevant Information

2.3 Marine Conservation Led by Resource Users

2.4 Terminology and Concurrent Processes

3. Public Comment Periods and Proposed Regulations

B. Role of Science: Ensuring Science-Based Decision-Making

C. Protection Standards: Ensuring Marine Biodiversity Benefits

D. Recognizing Community and Indigenous Conserved Areas

E. An Integrated Process: Marine Planning

1. Planning Frameworks and Partnerships

2. Integrated Marine Planning Processes

APPENDIX C: TRAVEL TO CANADA – WEST COAST From May 28 to June 2, 2017

APPENDIX D: TRAVEL TO CANADA – EAST COAST From October 16 to 20, 2017

REQUEST FOR GOVERNMENT RESPONSE

SUPPLEMENTARY OPINION OF THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY OF CANADA

SUPPLEMENTARY OPINION OF THE NEW DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF CANADA

Corolla spectabilis: Pteropod–The Race Rocks Taxonomy

Pteropods are occasionally found in the plankton that passes by Race Rocks and are found distributed throughout the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans..They have a transparent body with no external shell. An internal gelatinous pseudoconch provides protection and skeletal support. A continuous plate is formed by the oval wings which are marked by indentations.A long proboscis partially fused with the wing plate.The pteropod has a wingspan of up to 8cm. It lacks radula and jaws and it has a distinctive dark gut nucleus.Because it is planktonic, its biotic associations include predation by anything that eats jellyfish.

REFERENCE: ”Pacific Coast Pelagic Invertebrates” by David Wrobel and Claudia Mills—Note: This source had an error which was pointed out to us by Moira Galbraith of DFO:—-“I think that your video in the Race Rocks portion of the website is actually of Corolla spectabilis. The 12 mucous glands on the anterior lateral borders of the wing plate are a species characteristic; C.calceola will have 18. Also according to Carol Lalli, only Corolla spectabilis occurs in the eastern Pacific.

See http://faculty.washington.edu/cemills/ActaErrata.html for an update.

Domain: Eukarya

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Mollusca

Subclass: Opisthobranchia

Order: Thecosomata

(Suborder)(Pseudothecosomata)

Family: Cymbuliidae

Genus: Corolla

Species: spectabilis

Common Name: Pteropod

Other Members of the Phylum Mollusca at Race Rocks.

and Image File |

The Race Rocks taxonomy is a collaborative venture originally started with the Biology and Environmental Systems students of Lester Pearson College UWC. It now also has contributions added by Faculty, Staff, Volunteers and Observers on the remote control webcams. The Race Rocks taxonomy is a collaborative venture originally started with the Biology and Environmental Systems students of Lester Pearson College UWC. It now also has contributions added by Faculty, Staff, Volunteers and Observers on the remote control webcams. |

Cam 5 Eagle picture taken from England

Pam Birley sent this picture that she captured today of a pair of eagles.

she writes “The superb eagle pair were perched below Cam 5 today. ”

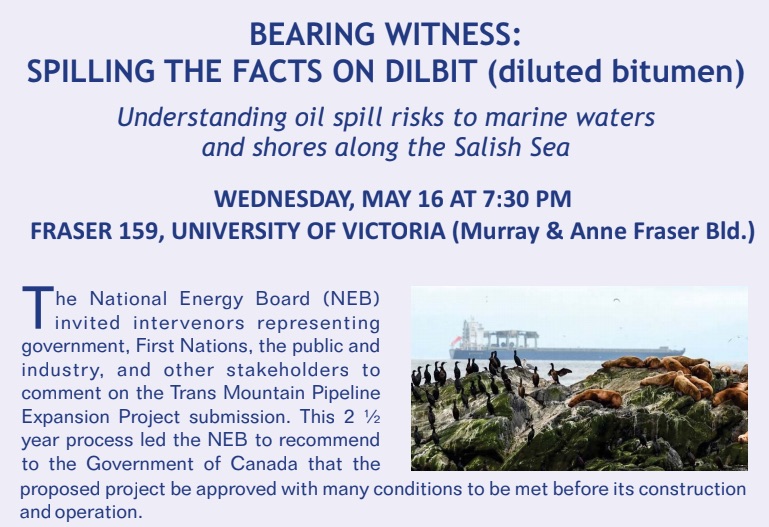

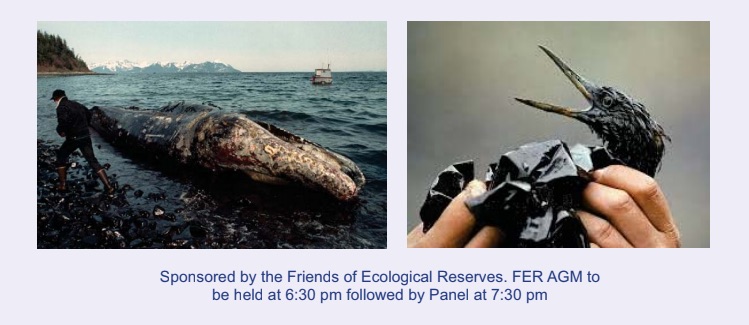

Bearing Witness: Spilling the Facts on Dilbit (diluted bitumen)

A major concern for those of us who work with Race Rocks is the impending disaster that is likely to happen to the Ecological reserve if the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain Pipeline is built. The Friends of Ecological Reserves is sponsoring the following panel discussion on threats to our Marine environment which has a good chance of happening if this pipeline gets built and the marine transport necessary for it goes within several kilometers of Race Rocks Ecological Reserve. Also see other posts on the Oil Spill Risk Link.

Pearson College and Race Rocks Video

Feature Article on Pam Birley,

From: TheThunderbird.ca News, analysis and commentary by UBC Journalism students

B.C. wildlife webcam protects ecosystem, entertains daily British watcher

Visit Pamela Birley in her Leicester, England, home, and you’ll likely see sea lions hauling themselves onto Great Race Rock – an island in B.C., eight time zones away.

Surrounded by tidal races, open to wind and waves, and dwarfed by views of the Olympic Mountains, the treeless rock off the southern tip of Vancouver Island is a magnet for marine life in the area.

A young elephant seal saunters towards the sea.

Photo: Hanne-Marie Barlach Christensen

Birley, 86, has been watching the wildlife on Great Race Rock, the exposed peak of the seamount comprising the Race Rocks marine ecological reserve, for the past 14 years.

The webcams have performed a unique function since they were installed in 2000 by drawing in visitors from around the world and keeping the public from overwhelming the ecosystem. Birley is a daily watcher.

“It’s the variety of wildlife out there,” she said. “You’re never too sure what you’re going to see, and sometimes you see unusual things.”

Hotspot for biodiversity

Home to millions of plankton, thousands of nesting seabirds, and hundreds of sea lions, the reserve in the Strait of Juan de Fuca is rich in marine life. It’s this diversity that motivated Garry Fletcher, a marine biologist, to push for the area’s protection in the 1970s.

“It’s at the confluence of upwelling from deeper ocean and the fresh water spilling out of the Georgia Basin, so it creates a very unique ecosystem,” Fletcher said. “It’s a real hotspot of biodiversity.”

Fletcher’s efforts paid off. In 1980, the B.C. government designated Race Rocks and surrounding seamount as a provincial marine protected area. The federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans subsequently closed the reserve to commercial and ground fishing in 1991 and has designated it an area of interest, slated to become a marine protected area. Spanning 226 hectares, the reserve is managed under lease by the nearby college where Fletcher taught until retirement, Lester B. Pearson United World College of the Pacific.

However, most of those 226 hectares are submerged. Great Race Rock, at merely two hectares, is the only habitable part of the reserve.

Easily crossed on foot in less than 10 minutes, the island has no safe harbour and is cut off from Vancouver Island for days during spells of bad weather. For the island’s resident eco-guardian, Laas Parnell, the island’s size and isolation are impossible to ignore.

Originally from Haida Gwaii, Parnell has lived in isolated, coastal places most of her life. Yet Race Rocks stole her heart when she first visited during a marine-science class in 2011.

“I love it here,” she said of her home of the past year. “I’m not claustrophobic. I keep pretty busy, cooking, cleaning. I spend a lot of time just walking around.”

Still, the island’s tininess can be humbling.

“It reminds me that I’m the only one out there. Alone.” she said.

Light keepers lived on Race Rocks until the beacon was automated in 1997. Their houses, the jetty, and the lighthouse outbuildings remain to house the eco-guardian, researchers, and students. Photo: Hanne-Marie Barlach Christensen

It’s an aspect of the island Birley hadn’t noticed through the webcam.

“It surprised me how compact it was when we actually visited,” she said, reminiscing on the first time she set foot on the island in 2007. “I find it hard to get my bearings on the webcam in relation to what’s near what.”

“Parks end up getting loved to death sometimes”

It was the island’s size that motivated Fletcher to install the webcams. Covered in resting sea lions or seabird nests most of the year, the island can’t handle many visitors. He worried about the impact tourism could have had on the area.

The island is isolated during the winter months by gales and tidal races, but calm seas in the summer make it within easy reach for boats leaving Victoria and other harbours along southern Vancouver Island.

“It’s a bird colony and marine mammal haul-out area,” said Fletcher. “It was just too sensitive to have people coming and going in hordes. You would have every whale-watching boat stop there and disgorge its passengers. Parks end up getting loved to death sometimes.”

To prevent over-visitation, BC Parks mandates that visitors to the island must obtain an education or research permit.

Gulls depend on Great Race Rock as a nesting site and a place to rest.

Photo: Hanne-Marie Barlach Christensen

However, Fletcher wanted to make the reserve’s unique biodiversity and natural beauty publicly available. At the time, webcams offered a novel solution.

Webcams connect wildlife lovers

In 2000, most Canadians relied on dial-up internet, Mark Zuckerberg was 16, and YouTube wouldn’t exist for another five years. Broadcasting online, live from Race Rocks, was a moment Fletcher won’t forget.

“My best memory is when we achieved getting the first video signals off the island, back in 2000,” said Fletcher. “That was quite an accomplishment and represented participation and co-operation from a lot of players.”

For Birley, the introduction of webcams like the ones at Race Rocks were an opportunity to explore the world. She watches four cams daily, including Race Rocks.

“I don’t get out a great deal now,” she said. “But my life is full: I get out in the garden and I do a lot of knitting. I knit birds, just little standing shelf sitters. I can knit while I watch the webcams, so it’s productive.”

Birley’s best-selling knit bird: a peregrine falcon. Photo: Pamela Birley/Etsy

Birley’s knitted birds are popular: she’s sold hundreds in her Etsy shop to buyers far and wide.

Webcams have also fostered international friendships for Birley. Fletcher is one of her regular correspondents, and she’s made friends in Victoria and Seattle through webcams.

It is the animals, however, that keep Birley watching Race Rocks. She documents Race Rocks wildlife extensively through webcam screenshots and turns them into albums on Flickr.

Birley sees some animals regularly, like the gulls and sea lions, but her dedication to the webcam has paid off with an amazing sighting—a snowy owl.

“It was pouring rain, I had the camera on, and I was probably knitting,” she recalls.

“I looked up and thought I saw a funny looking seagull by the rock. I zoomed in and there it was: a snowy owl sitting there, just swivelling its head around from time to time. I’ve only ever seen the one, and that was quite exciting!”

Seeing a snowy owl was a highlight of Birley’s webcam sightings.

Photo: Pamela Birley/Race Rocks

Views From England

Today I received a nice note from Pam Birley, our devoted follower from Leicestershire Great Britain who often captures great images with our remote cameras. She writes: “Couldn’t resist taking these pics today. Spectacular views this morning at RR. ”

Note the nictitating membrane on the right

So I just went on camera 5 and found one of the eagles still in close range:

Guillemots are back

I just received this email from Pam Birley ” The Pigeon Guillemots are back ! They are even earlier this year. It is usually February when I first see them.” Thanks Pam for the observation from Leiscester England! Laas has also been out getting pictures of them.

It is also interesting to note that the elephant seal pup is doing very well this year. As Ecoguardian Laas Parnell has noted the one large male tends to keep the others on the island at bay. Hopefully this year the pup can survive once the mother leaves and it becomes a weaner. In most of the past years since pups first started being born on the island, aggressive males have led to a tragic end. I have requested BC Parks and DFO to produce a policy on what support can be offered in the event a pup is injured in the crucial period before it goes to the ocean after its month long weaning period. So far this has not been acted upon, so again this year it will be left up to chance, and hopefully the so-far protective bull will remain that way. The following pictures are from Camera1 at the top of the tower on Race Rocks.

- Elephant seal mother and 2.5 week old pup

- Elephant seal female,pup and male

Dr. Anita Brinkmann-Voss…. In Memoriam

Dr. Anita Brinckmann-Voss passed away on December 12 at her home in Sooke BC. Anita had been a long time friend of Lester B. Pearson College. From 1986, to 2005, Dr. Anita Brinckmann-Voss BC assisted the students and faculty of Lester Pearson College with her understanding of marine invertebrate ecology and her expertise in the taxonomy of hydroids and other invertebrates. Anita was one of the very few remaining taxonomists in the world who worked at such depth with this group of organisms. She assisted many students with their work in biology and marine science and worked closely with several divers at the college who collected specimens for her. Anita also was a regular donor to the Race Rocks program at the college.

Dr. Anita Brinckmann-Voss passed away on December 12 at her home in Sooke BC. Anita had been a long time friend of Lester B. Pearson College. From 1986, to 2005, Dr. Anita Brinckmann-Voss BC assisted the students and faculty of Lester Pearson College with her understanding of marine invertebrate ecology and her expertise in the taxonomy of hydroids and other invertebrates. Anita was one of the very few remaining taxonomists in the world who worked at such depth with this group of organisms. She assisted many students with their work in biology and marine science and worked closely with several divers at the college who collected specimens for her. Anita also was a regular donor to the Race Rocks program at the college.

Dr. Dale Calder, a colleague of Anita who works with the Royal Ontario Museum wrote the following about Anita:

“I knew of Dr. Anita Brinckmann-Voss and her research on hydrozoans from my days as a graduate student in Virginia during the 1960s. Her work at the famous Stazione Zoologica in Naples, Italy, was already widely known and respected.

Most noteworthy, however, was a landmark publication to come: her monumental monograph on hydrozoans of the Gulf of Naples, published in 1970. It highlighted studies on hydrozoan life cycles and was accompanied by the most beautiful illustrations of these marine animals that have ever been created. See the complete copy with color plates here: Brinckmann70:

Most noteworthy, however, was a landmark publication to come: her monumental monograph on hydrozoans of the Gulf of Naples, published in 1970. It highlighted studies on hydrozoan life cycles and was accompanied by the most beautiful illustrations of these marine animals that have ever been created. See the complete copy with color plates here: Brinckmann70:

It was not until 1974, and the Third International Conference on Coelenterate Biology in Victoria, British Columbia (BC), Canada, that I met her for the first time. We discovered having common scientific interests and saw absolutely eye-to-eye on most issues. It was the beginning of a scientific collaboration and friendship that would last a lifetime. I always greatly valued her scientific insights, but I also appreciated her humility, good nature, and keen sense of humour.

In having moved from Europe to Canada, first to Winnipeg, Manitoba, and later to Toronto, Ontario, Anita’s research shifted from Mediterranean species to those of Canadian waters and especially British Columbia. Her professional base became the Royal Ontario Museum and the University of Toronto, but it was far from the ocean. She soon acquired a residence in Sooke, BC, conveniently located on the beautiful Pacific coast. Life cycle research was now possible on Canadian species, and at times several hundred cultures of hydrozoans were being maintained by her. One final move was made, from Ontario to permanent residence at her cottage in Sooke. From there she kept marine research underway the rest of her life. A focus became Race Rocks and the rich hydrozoan fauna inhabiting the site.

Anita altered the direction of my career in a most positive way. It was largely thanks to her that I moved from employment as a benthic ecologist in South Carolina to a curatorial position at the Royal Ontario Museum in 1981. It was the best career move of my life. Thank you, Anita!

Over the decades we collaborated in research, shared our libraries, and jointly authored several scientific papers. Outside a professional association, we were close friends. My wife and I often visited Anita at her homes, first in Pickering, Ontario, near Toronto, and later in Sooke. In return, she often visited us in Toronto after moving west. It is an understatement to say she will be sorely missed.”

-(Quote from Dr. Dale Calder, ROM, 2018)

Links to her work with the college:

https://www.racerocks.ca/dr-anita-brinckmann-voss/

Other references: https://www.racerocks.ca/tag/anita-brinckmann-voss/