This draft version has been replaced by a newer versionProceed to this link

Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area

(RR ER-MPA) Draft Management Plan

Table of Contents

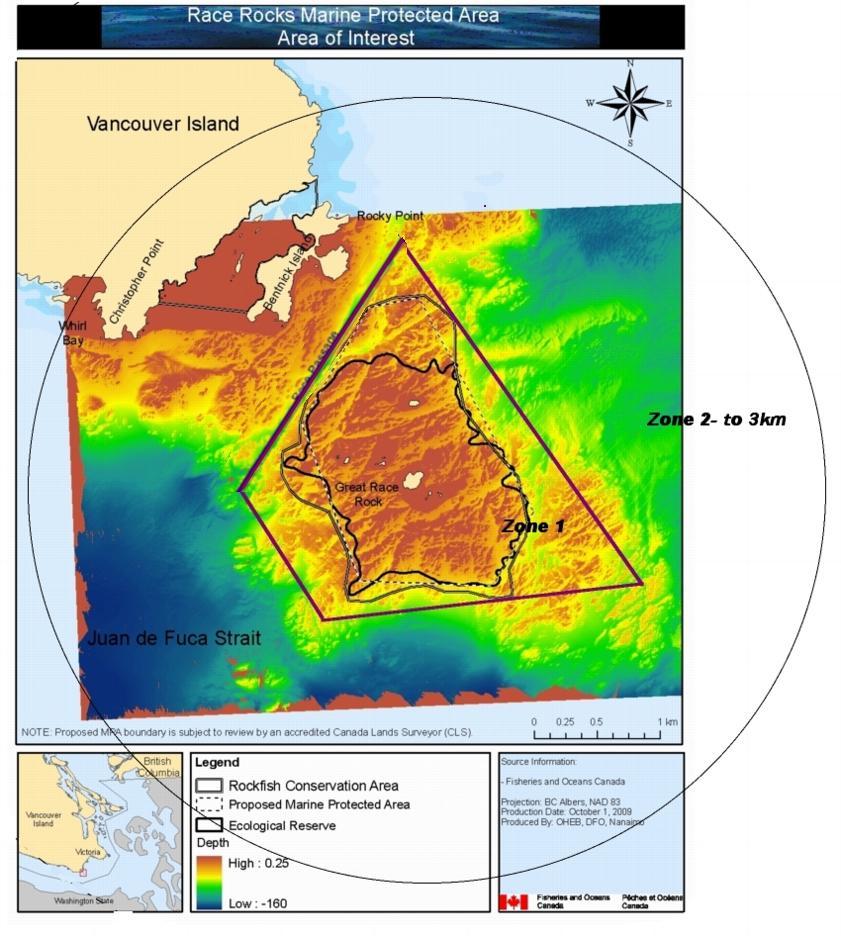

- Map

- Executive Summary

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Objectives, Background and Action?

- Key Management Issues?

- Appendix 1: Ecosystem Overview?

Map

Executive Summary

Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area will be managed to protect the rich intertidal communities and to encourage educational and research benefits while minimizing impacts.

The relationship with Lester B. Pearson College will be formalized to assist in the education, research and management of the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

The addition of Great Race Rock will be pursued to protect the integrity of the area and its values. If Great Race Rocks is acquired the lighthouse lands will be designated as a Protected Area under the Environment and Land Use Act. The former lighthouse buildings will be operated in conjunction with Lester B. Pearson College (under permit) and other partners as an education and research centre to complement the intent of the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area.

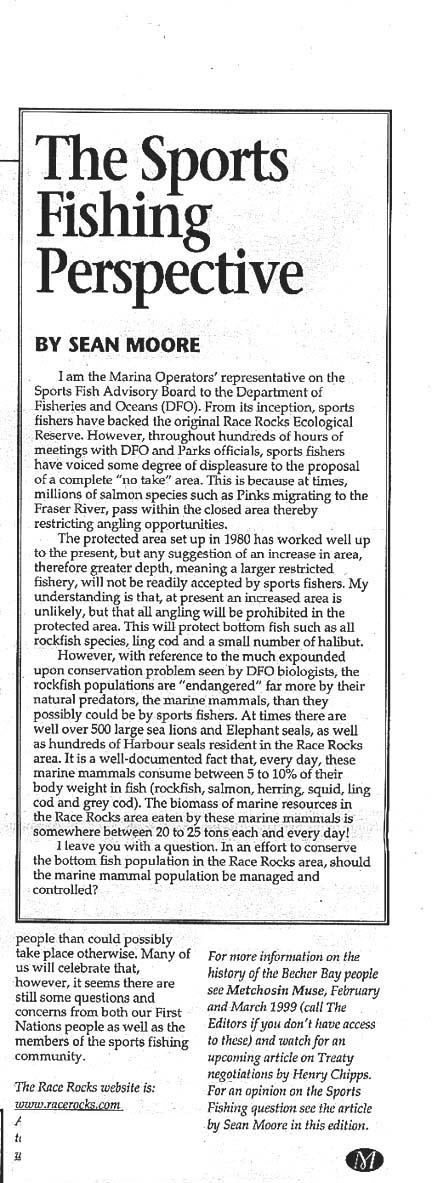

To provide increased protection to resident groundfish populations, BC Parks will, in consultation with DFO and stakeholders and through direction provided by the emerging joint federal-provincial Marine Protected Areas Strategy, investigate the implications and feasibility of implementing full recreational harvesting closures in Race Rocks either under the federal Fisheries Act or designating the area as a Marine Protected Area under the Oceans Act.

The plan was coordinated by Kris Kennett, BC Parks Planner. Garry Fletcher of Lester B. Pearson College developed the initial draft plan, and provided expert knowledge and information. Assistance and expertise was provided by various BC Parks staff including: David Chater, District Manager; Chris Kissinger, Resource Officer; Don McLaren, Area Supervisor; Mona Holley, Acting Wildlife Ecologist; Doug Biffard, Marine Ecologist; Ken Morrison, Conservation Planner and Jim Morris, District Planner and Fisheries and Oceans staff: Doug Andrie, Integrated Coastal Zone Management Coordinator; and, Marc Pakenham, Community Advisor.

The objective of the ecological reserve – marine protected area strategy in British Columbia is the conservation of representative and special natural ecosystems, plants and animal species, features and phenomena. Ecological reserves and marine protected areas contribute to the maintenance of biological diversity and the protection of genetic materials. They also offer opportunities for scientific research and educational activities. In many ecological reserve – marine protected areas, non-consumptive low-intensity uses such as nature appreciation, wildlife viewing, bird watching and photography are allowed and Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – marine protected area – Marine Protected Area features many of these activities.

Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area was created to protect a unique small rocky island system, intertidal areas and high current subtidal area in the eastern entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. It is located off the southern tip of Vancouver Island, approximately 17 km. southwest of Victoria. It covers an area of 220 ha and includes nine islets, but does not include Great Race Rock. It was established in 1980 as a result of a proposal by the students and faculty of Lester B. Pearson College.

Purpose of the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve — Marine Protected Area Feasibility Study Plan

This plan defines management goals and objectives for Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area. It provides the strategies and guidance necessary to protect and manage the ecological reserve – marine protected area, particularly concerning the protection of natural values, recreation use, research and education uses. The management plan will be the working tool that will require periodic updating. Specific recommendations are documented for a multi-year management program.

Race Rocks Ecological Reserve — Marine Protected Area will continue to protect the high-energy marine system found in the eastern entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Research will assist in the management of the ecological reserve – marine protected area and contribute to the knowledge base of marine systems. The ecological reserve – marine protected area will provide opportunities to increase the awareness of students, visitors and the general public about marine systems and the ecological reserve – marine protected area program. Lester B. Pearson College and the surrounding community will play a large role in the education, research and management of this area. Non-consumptive low-intensity educational uses such as nature appreciation, wildlife viewing, bird watching and photography will continue.

- To contribute to the protection of marine biodiversity, representative ecosystems and special natural features.

- To contribute to the conservation and protection of fishery resources and their habitats.

- To contribute to the protection of cultural heritage resources and encourage understanding and appreciation.

- To support recreation and tourism opportunities.

- To provide scientific research opportunities and support sharing of traditional knowledge.

- To enhance efforts for increased education and awareness.

- To develop partnerships for management and protection of the ecological reserve – marine protected including monitoring and reporting activities.

- To develop working relationships and educational programs with First Nations

Objectives, Background and Action

1. Objective:

To contribute to the protection of marine biodiversity, representative ecosystems and special natural features.

Establishing boundaries is a difficult task, given the problems associated with establishing ‘markers’ in a marine environment. The present boundaries were determined by the normal limits of SCUBA diving and based on the contours of the nautical charts of the time. This has created a situation where features are not captured and the boundary is not well-defined. In addition, metric charts are now the standard which makes the ‘fathom’ description more difficult to determine.

The ecological reserve is protected under the Ecological Reserve Act and the Ecological Reserve Regulations. In addition, the penalty provisions of the Park Act can now be used to assist in protecting the ecological reserve – marine protected area and its values. Organisms in the water column are not subject to provincial legislation, being under the jurisdiction of the federal government.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada can manage marine resources under the Fisheries Act and the new Oceans Act. The Oceans Act, enacted in January 1997, also gives DFO the authority to establish Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Under this Act, MPAs can be established for a number of purposes, including conservation and protection of: commercial and non-commercial fisheries resourced; marine mammals and their habitats; endangered or threatened species and their habitats; unique habitats; and areas of high biodiversity or biological productivity. Race Rocks Ecological Reserve and its values, particularly the protection of resident groundfish populations, would benefit from the implementation of full harvesting closures under the Fisheries Act or designating it as a Marine Protected Area under the Oceans Act.

Great Race Rock is surrounded by the ecological reserve – marine protected area but is not part of it. It is the largest island in the group and supports a lighthouse station, which is federally administered. Recently, the federal government has been automating lighthouses and returning surplus Crown provincial land to the provincial government for others uses. BC Parks has the opportunity to add Great Race Rock to the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

In conjunction with DFO, investigate opportunities to expand the boundary from the existing 36.5 m (20 fathom) contour to the 50 m contour.

Investigate opportunities to establish global position system coordinates for identification of the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

Identify ecological reserve – marine protected area boundaries on marine charts and related marine guides and publications.

BC Parks will, through consultations with other agencies, such as DFO and stakeholders and through direction provided by the emerging joint federal-provincial Marine Protected Areas Strategy, investigate the implications and feasibility of implementing full recreational and commercial harvesting closures in Race Rocks either under the federal Fisheries Act or designating the area as a Marine Protected Area under the Oceans Act.

Develop a protocol agreement with DFO to ensure consistent management of the water column and the land base.

Pursue the addition of Great Race Rock to the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

- Cooperate with Parks Canada and their national marine conservation area feasibility study.

To contribute to the conservation and protection of fishery resources and their habitats.

Race Rocks Ecological Reserve protects a provincially, if not nationally, significant high-current subtidal and intertidal ecosystem. The reserve has ecologically significant and unique assemblages of benthic and pelagic invertebrates. It protects several rare species, including the spiral white snail Opalia, and many rare hydroid species (such as Rhysia fletcheri), that represent unique Canadian or North American occurrences and provides haul outs and feeding areas for elephant seals, sea lions, breeding areas for harbour seals and nesting habitat and migrating resting areas for seabirds.

In 1991, DFO closed Race Rocks Ecological Reserve to commercial fin and shellfish harvesting for all species. Race Rocks is also closed to recreational harvest of shellfish, ling cod and rock fish but remains open for salmon and halibut. Fishing for salmon still occurs inside the ecological reserve – marine protected area boundaries, whereas halibut is largely found in the deeper, adjacent waters.

Oil spills next to the ecological reserve – marine protected area could potentially be devastating to the sensitive intertidal communities, marine mammal and bird populations. The ecological reserve – marine protected area probably has a relatively short time for self cleansing given its location in a high current zone with high energy exposure from both easterly and westerly winds in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. However, options for protection of this valuable ecosystem in the event of an oil spill should be investigated.

The lighthouse station on Great Race Rock poses two threats to the marine environment. First, sewage from the residences is being discharged directly into the water column. Although the extreme tidal flushing lessens the impact, this situation is not appropriate in an highly valued marine environment. Second, electricicty is provided by diesel generators, and diesel spills pose a hazard to the environment. Alternative technologies for sewage treatment and power generation, such as composting toilets and solar energy, should be investigated. Composting toilet has already been installed in assistant’s residence.

Visitors to the ecological reserve – marine protected area can severely impact the delicate underwater communities by anchoring, or disturb nesting sea birds or resting sea lions and seals by landing or passing too close to these small islets. Boats driven in the reserve at high speeds endanger the marine mammals.

Develop a marine management plan to ensure protection of intertidal and rare species and to ensure that elephant seals, harbour seals, California and Steller’s sea lions, and seabirds are not disturbed on their haulout and nesting sites.

In conjunction with Lester B. Pearson College and commercial tour operators, develop a code of conduct for visiting the ecological reserve – marine protected area to ensure protection of natural values and to maintain a high quality educational experience (including speed restrictions).

Discourage landings on islands through the provision of information and permit requirement.

Discourage anchoring in the ecological reserve – marine protected area through the provision of information.

In conjunction with Marine Protected Areas Strategy initiative, work with DFO in consulting all stakeholders to explore the implementation of full harvesting closures under either the Fisheries Act or the Oceans Act in order to assist in the protection of resident groundfish populations.

Ensure the recognition and clear information of the boundaries of the ecological reserve – marine protected area, speed limits and its protective status are clearly described in the BC Sports Fishing Regulations, on marine charts and guides.

In conjunction with the Oil Spill Recovery Information System (OSRIS), develop and register a strategy for protection of the ecological reserve – marine protected area in the event of an oil spill.

Work with the federal government to clean up and improve the site, including the removal of the present sewage disposal facilities and diesel tanks. Pursue opportunities for compensation. Investigate opportunities to utilize alternative technologies. Monitor technology that supports more intensive use remotely with less impact on the ecological values. Institute a monitoring program to determine marine and terrestrial site degradation or enhancement within the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

To contribute to the protection of cultural heritage resources and encourage understanding and appreciation.

One of the main objectives of the ecological reserve – marine protected area program is to provide opportunities for scientific research. Race Rocks Ecological Reserve has been very successful at fulfilling this objective through the interests and actions of Lester B. Pearson College. The college undertakes and assists in most of the research conducted at Race Rocks. The students and faculty provide local knowledge, orientation services and willing assistants to other researchers. They also monitor permanent transects and conduct their own research as part of their course requirements.

BC Parks encourages research that contributes to the long-term protection and understanding of ecosystems. Research priorities reflect BC Parks’ mandate, with emphasis on conservation objectives, acute and chronic management problems, and rare and endangered species. To achieve this, research proposals are subjected to a systematic review process. The collected data are required to be made available and shared with the scientific community. As required by the Ecological Reserve Regulations, researchers must require a permit through BC Parks to legitimize their activities.

In the past, Lester B. Pearson College developed a good working relationship with the Coast Guard and the lighthouse keepers. The College was able to use some of the buildings to assist in their research. With the automation of lighthouses, Lester B. Pearson College has taken the opportunity of formalizing the use of the surplus buildings for a two-year period ending in 1999 and presently (since March 1997) employed the former light keepers to stay at Race Rocks. The College proposes to continue to utilize the facilities as an education and research centre.

Action:

With assistance from Lester B. Pearson College and other researchers, develop a long-term research and monitoring plan to minimize impact to ecological reserve – marine protected area values and maximize research opportunities and benefits.

Ensure all researchers have permits.

Operate buildings on Great Race Rock as a research and education centre, as funding permits. Work with community groups such as Lester B. Pearson College and other partners for the ongoing operation and funding for such as facility through a long term permit.

Develop a comprehensive permit with Lester B. Pearson College which define roles and responsibilities for education, research and management.

4.) To support tourism recreation and tourism ( this objuective was not completed inthe original)

5 Objective:

To provide scientific research opportunities and support sharing of traditional knowledge.

Education is another objective of ecological reserve – marine protected areas. Since the late 1970s, Lester B. Pearson College has been using the ecological reserve – marine protected area as an outdoor classroom and educational facility for students from both the college and local schools. In addition, groups like Friends of Ecological reserve, naturalists, and commercial operators visit the ecological reserve – marine protected area as part of their education programs.

Films and live televised programs such as the “Underwater Safari” series assist in developing an appreciation of the biodiversity with little impact on the ecological reserve – marine protected area. Approval for filming takes into account the purpose of the filming and the type of footage in relation to the purpose of the ecological reserve – marine protected area and the current inventory of ‘stock’ footage available.

The Internet is another means of education. In 1995, Lester B. Pearson College established files connected to their website with information on Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – marine protected area – Marine Protected Area, an ecological reserve – marine protected area publications list and intertidal photographic transects. Since that time the site has expanded to include more records of research, profiles of organisms, tidepools, as well as history. This has raised awareness globally and has resulted in students from other parts of the world undertaking comparative studies.

Race Rocks has a colorful marine history, with the ships that sunk as a result of the rocks and the building of the lighthouse. Little is known about First Nations historical interests and use of the ecological reserve – marine protected area. The college has established an archive on the internet of relevant historical information and images.

Undertake proactive measures to provide educational information to the public and visitors. Ensure accurate information in fishery regulations, provide information at points of entry (such as marinas); ensure the ecological reserve – marine protected area is mapped on marine charts and navigation guides.

Work with Lester B. Pearson College and other community groups to provide: low impact educational opportunities for schools and the community; offsite educational opportunities; and information on the Internet.

Continue to permit filming for only educational and research purposes. Develop stock footage to respond to standard filming requests.

Monitor the level of educational use and take management actions where necessary and in consultation with Lester B. Pearson College, commercial tour operators and others.

Develop, in consultation with Lester B. Pearson College and First Nations, educational information on ecosystems and the cultural and marine history of Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area.

Update existing Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area brochure to reflect management direction established in this plan.

To permit educational opportunities that have minimal impact to the ecological reserve – marine protected area and increase public awareness, understanding and appreciation for Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area and its values.

Background:

Ecological reserve – marine protected areas are established to support research and educational activities. Visitation to the waters surrounding Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – marine protected area – Marine Protected Area has been increasing, particularly those engaged in wild life viewing and diving. Uncontrolled, uninformed and excessive use could result in: behavioral changes or injury to marine mammals and seabirds; poaching of sealife; or physical injury or mortality from handling or improper dive techniques. Given the proximity of the ecological reserve – marine protected area to Victoria and the interest in these types of activities, commercial and recreation use will continue to grow.

Given the roles of ecological reserves – marine protected areas, uses that occur at Race Rocks should contribute to education or research objectives without negatively impacting the natural values. This may include commercial tours.

Subject to an impact assessment, only issue permits for commercial activities that are educational or research oriented.

Work with the volunteer warden, Lester B. Pearson College, to provide annual orientation session for commercial operators and tour guides. Continue to provide public information to increase awareness of the ecological reserve – marine protected area, the potential of ecological impact of various activities, and the need for caution in the ecological reserve – marine protected area. This would include: brochure; accurate information in BC Sports Fishing Regulations; information at points of entry; mapping on marine charts and navigational guides; internet/web site.

Work with commercial operators and researchers to develop a code of conduct within the ecological reserve – marine protected area to ensure protection of the natural values and to maintain a high quality educational experience. Develop a monitoring system with Lester B. Pearson College, site guardian, researchers and commercial tour operators to ensure appropriate behavior of diving and wild life viewing companies and other visitors.

Develop an outreach program and stewards program to assist with the management, and to develop respect for the ecological reserve – marine protected area and its values.

Discourage anchoring in the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

As per the Ecological reserve – marine protected area Regulations ensure that commercial operators in the ecological reserve – marine protected area have permits for their activities.

To enhance efforts for increased education and awareness.

Commercial and sports fishing, nature tours, marine traffic, and explosives testing occur in the waters surrounding the ecological reserve – marine protected area. Presently, a part of Great Race Rock is administered by the federal government and partly by Lester B. Pearson College. Although most of the land base will be returned to the Province, the tower, which has been automated, will continue to be administered by the Canadian Coast Guard.

A number of federal and provincial initiatives for planning in the marine environment are either proposed or underway. These include the Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy, Marine Protected Areas Strategy and strategic planning for marine areas that is consistent with the Vancouver Island Land Use Plan.

Establish communications with CFB Esquimalt to determine the impact of nearby explosives testing on, the ecological reserve – marine protected area, and develop mitigative measures if necessary.

Work with DFO to lessen the impact of fishing, whale watching, seal and sea lion observing and bird watching.

Before Great Race Rock property reverts to the Province, work with federal government to clean up and improve site, including the removal of sewage disposal facilities and diesel tanks. Pursue opportunities for compensation. Investigate opportunities to utilize alternative technologies.

Develop protocol with Coast Guard for their continuing operation of the light tower, including helicopter landings, marine access, repairs.

Work with federal and provincial agencies in marine planning initiatives.

To develop partnerships for management and protection of the ecological reserve – marine protected including monitoring and reporting activities.

Under the volunteer program, BC Parks has an ecological reserve – marine protected area warden program to provide on-site monitoring and reporting on ecological reserve – marine protected areas. Since the establishment of Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area, the Biology and Environmental Systems faculty and students at Lester B. Pearson College have taken on the role of warden. They were greatly assisted by the former lighthouse keepers stationed at Race Rocks who monitored activities in the ecological reserve – marine protected area and reported violations such as commercial fishing, shooting of sea lions and oiled birds on islands. Since the automation of the lighthouse, the college has an interim agreement with the Coast Guard to use the facilities for the next two years and they have generated private funding to keep the former lighthouse keeper in place as a guardian until March 1, 1998. The role of the site guardian is to support Pearson College’s activities on the island and alsoupport the College’s ecological reserve – marine protected area warden duties (e.g. provide information and report violations).

BC Parks is now developing a broader conservation stewardship initiative under the volunteer program. This program will encourage community involvement in the stewardship of parks and ecological reserve – marine protected areas. Given the interest in Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – marine protected area – Marine Protected Area and its proximity to an urban centre, there are opportunities to implement the program here. The integrity of the ecological reserve – marine protected area will be assisted by involving tour operators and other interests in the stewardship of Race Rocks.

- Work with Lester B. Pearson College as host warden to assist in the management of the ecological reserve – marine protected area. Develop a protocol agreement to define relationship and outline roles and responsibilities for education, research and management, including operation of research facility on Great Race Rock.

- In consultation with the volunteer warden, Lester B. Pearson College, develop opportunities for operators, naturalists and others to contribute to the stewardship of the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

- Develop procedures to report violations in order to assist with enforcement.

- Work with Lester B. Pearson College to provide a presence or guardian to assist in information distribution, education, monitoring and reporting of violations.

- Work with DFO and the Coast Guard to enforce site-specific fisheries regulations and objectives.

8Objective:

To develop working relationships and educational programs with First Nations

First Nation interests and traditional uses of Race Rocks are not documented. A good working relationship between BC Parks and the First Nations people is needed to ensure BC Parks is fulfilling its fiduciary obligations and to develop a mutual understanding of the values of the ecological reserve – marine protected area and its ongoing protection.

Consult with representatives from the Beecher Bay, T’souke, Songhees and Esquimalt First Nations to understand the traditional uses of Race Rocks ecological reserve – marine protected area.

Ensure regular communication on ecological reserve – marine protected area management issues.

- Investigate opportunities to undertake a traditional use and education study.

- Establish joint management initiatives.

KEY MANAGEMENT ISSUES

Relationship with Other Land Use Planning

Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area Boundaries

Cooperation with the Federal Government

Cooperation with Lester B. Pearson College

Management of Research Activities and Facilities

Management of Education Activities

Management of Recreation and Commercial Activities

Conservation and Representation

Surrounding Land Use

Community Stewardship

Relationship with First Nations

Relationship with Other Land Use Planning

Management planning processes provide a mechanism for public review and support for management strategies. In this respect, an ecological reserve – marine protected area management plan must be considered in terms of its relationship with other land use strategies.

In June 1994, the provincial government announced the Vancouver Island Land Use Plan. This plan recommended that strategic planning occur for marine areas. Marine planning units have now been identified and planning framework statements summarizing values and capabilities have been prepared for the next level of planning. Race Rocks and surrounding areas are included in this process.

The marine environment of the Pacific coast is not well represented in either federal or provincial protected areas systems. The federal and provincial governments are committed to establishing a system of marine protected areas and are developing a strategy to this end. A separate but related initiative is the Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy (PMHL), where the federal and provincial governments are working to form a network of coastal and marine protected areas along the southern Pacific coast. Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area is situated adjacent to a study area for a national marine conservation feasibility study which will be initiated in 1998-99 as part of the PMHL Program.

Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area Boundaries

The ecological reserve – marine protected area includes an area of ocean, nine small islands and reefs bounded by the 36.6 metres contour, which is an outdated notation that does not follow natural features. Because of the presence of the Canadian Coast Guard light station, Great Race Rock has not been included in the ecological reserve – marine protected area. With the decommissioning of these stations, Great Race Rock is available to be added to the ecological reserve – marine protected area to enhance its integrity.

Cooperation with the Federal Government

Jurisdictional responsibilities for the management of the marine environment and marine resources are shared between the federal and provincial governments. For example DFP is responsible for organisms in the water column. The Coast Guard is presently reponsible for the management of Great Race Race Rock. The province has jurisdication over the other islands and the land under the water column. The provincial government is working with federal government agencies of DFO, Parks Canada and Environment Canada to develop and implement a marine protected areas strategy, and with Parks Canada to implement the PMHL program. The Canadian Forces Base (CFB) in Esquimalt tests explosives in the area, which may impact the ecological reserve – marine protected area’s values. Cooperation with the Coast Guard, DFO, Parks Canada and CFB Esquimalt is essential to ensure the best protection for the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

Cooperation with Lester B. Pearson College

Lester B. Pearson College was instrumental in the establishment of the ecological reserve – marine protected area. The faculty and students of the Biology and Environmental Systems program at Pearson College are long-time volunteer ecological reserve – marine protected area wardens. They are actively involved in research and education activities and provide an important monitoring function. Lester B. Pearson College has a temporary agreement with the Coast Guard to operate a research station at the lighthouse on Great Race Rock. Clarification of roles and responsibilities of both Lester B. Pearson College and BC Parks are needed to ensure successful management of the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

Management of Research Activities and Facilities

Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area provides outstanding marine research opportunities. Lester B. Pearson College has been the principal research agency and has developed a good database for the ecological reserve – marine protected area and its values. The College has pursued options to use the decommissioned lighthouse buildings as a research and education facility and guardian base.

Management of Education Activities

Given the proximity of an urban centre, Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area provides excellent educational opportunities. Lester B. Pearson College uses Race Rocks for their marine ecology program for college and local school students and naturalists. Tourism operators from Victoria offer educational nature tours as well. These activities must be managed to ensure protection of the values of the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

Management of Recreation and Commercial Activities

Commercial and non-commercial recreation activities such as wild life viewing, diving, boating and nature appreciation occur in the ecological reserve – marine protected area, both in the water and on land. These activities require cooperative management with the federal government, tour operators and recreational users to ensure that the values of the ecological reserve – marine protected area are maintained.

Background Summary

The Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area Background Report (Appendix 1) provides information on the ecological reserve – marine protected area to provide the basic information and assist in understanding the rationale behind the management plan.

This section compiles all the actions listed through this plan into three categories.

The implementation plan is divided into three components: ongoing management, priority one actions, and priority two actions.

Discourage anchoring and landings on islands in the ecological reserve – marine protected area through the provision of information.

Undertake proactive measures to increase awareness of the ecological reserve – marine protected area, the potential of ecological impact of various activities and the need for caution in the ecological reserve – marine protected area. This would include providing information such as the ecological reserve – marine protected area brochure at points of entry and ensuring accurate information and mapping in BC Sports Fishing Regulations, marine charts and navigational guide.

Only issue permits for activities that are educational or research oriented. Ensure all researchers and commercial operators have permits.

Work with Lester B. Pearson College and other community groups to provide: low impact educational opportunities for schools and the community; offsite educational opportunities; annual orientation session for commercial operators and tour guides; and information on the Internet.

Continue to permit filming for only educational and research purposes. Develop stock footage to respond to standard filming requests.

In consultation with Lester B. Pearson College as the ecological reserve – marine protected area warden, monitor the level of educational use and take management actions where necessary. This may include a site guardian to assist in information distribution, education, monitoring and reporting of violations to BC Parks.

Establish communications with CFB Esquimalt to limit testing near, and impact on, the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

- Work with DFO and the Coast Guard to protect the values of the ecological reserve – marine protected area and to lessen the impact of fishing, whale watching and seal and sea lion observing.

Ensure regular communication with First Nations on ecological reserve – marine protected area management issues.

Develop a protocol agreement with DFO to ensure consistent management of the water column and the land base.

Pursue the addition of Great Race Rock to the ecological reserve – marine protected area. ( done in 2002)

Support the application of Park Act Regulations and penalties to ecological reserve – marine protected areas.

Cooperate with federal and intergovernmental initiatives such as Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy, Marine Protected Areas Strategy, Parks Canada’s national marine conservation area feasibility study, and other marine planning initiatives.

Work with operators and researchers to develop code of conduct within the ecological reserve – marine protected area to ensure protection of the natural values and to maintain a high quality educational experience.

Work with the federal government to clean up and improve site, including the sewage disposal facilities and diesel tanks. Pursue opportunities for compensation. Investigate opportunities to utilize alternative technologies.

With assistance from Lester B. Pearson College and other researchers, develop a long-term research and monitoring plan to minimize impact to ecological reserve – marine protected area values and maximize research opportunities and benefits.

- Develop a protocol agreement with Lester B. Pearson College to define relationship and outline roles and responsibilities for education, research, and management issues, including operation of a research facility on Great Race Rocks. Develop a comprehensive research and park use permit with Lester B. Pearson College.

Operate buildings on Great Race Rock as research education centre, as funding permits. Work with community group such as Lester B. Pearson College for the ongoing operation and funding for such as facility through a long term permit.

Develop a monitoring system with Lester B. Pearson College, guardian, researchers and operators to ensure that appropriate behavior of diving and whale watching companies.

Develop protocol with Coast Guard for their continuing operation of the light tower, including helicopter landings, marine access, repairs.

Develop procedures to report violations in order to assist with enforcement.

Consult with representatives from the Beecher Bay and T’souke First Nations to determine their traditional use in the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

Develop a marine management plan to ensure protection of intertidal and rare species and to ensure that elephant seals, harbour seals, California and northern sea lions, and seabirds are not disturbed on their haulout and nesting sites.

In conjunction with DFO, investigate opportunities to expand the boundary from the existing 36.5 m (20 fathom) contour to the 50 m contour.

Investigate opportunities to establish global position system coordinates for identification of the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

In conjunction with the MPA Strategy initiative, pursue the feasibility of establishing Race Rocks as a marine protected area under the Oceans Act.

In conjunction with OSRIS, develop and register a strategy for protection of the ecological reserve – marine protected area in the event of an oil spill.

Develop, in consultation with Lester B. Pearson College and First Nations, educational information on ecosystems, history and culture of Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area.

Develop outreach program and stewards program to assist with the management, and develop respect for the ecological reserve – marine protected area and its values.

- In consultation with Lester B. Pearson College, develop opportunities for operators, naturalists and others to contribute to the stewardship of the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

Investigate opportunities to undertake a traditional use study.

Appendix 1: Ecosystem Overview

The objective of the ecological reserve – marine protected area program is to preserve representative and special natural ecosystems, plants and animal species, features and phenomena. Ecological reserve – marine protected areas contribute to the maintenance of biological diversity and the protection of genetic materials. Scientific and educational activities are the principal reasons for ecological reserve – marine protected areas. Most ecological reserve – marine protected areas are open to the public for uses that are non-consumptive, educational, low-intensity such as natural appreciation, wildlife viewing, bird watching and photography.

Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area was created to protect an unique small rocky island system, intertidal and high current subtidal areas in the eastern entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. It has ecologically significant and unique assemblages of benthic and pelagic invertebrates. In addition, it is a haul out and feeding areas for seals and sea lions and a nesting and staging area for seabirds.

Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area Description

Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – marine protected area – Marine Protected Area is located 17 km south west of Victoria at 123∞ 31.85’W latitude and 48∞ 17.95’N longitude. It is 1.5 km off the extreme southern tip of Vancouver Island at the eastern end of Strait of Juan de Fuca. Given the marine environment, access is limited. A Canadian Coast Guard helicopter pad is located on Great Race Rocks (which is excluded from the ecological reserve – marine protected area). Only seaworthy vessels are able to approach the ecological reserve – marine protected area, given the extreme sea conditions and lack of sheltered moorage.

The ecological reserve – marine protected area is 220 ha to a depth of 20 fathoms (36.6 metres). It is almost entirely subtidal, although nine islets comprise less than 1 ha. The present boundaries were determined by the normal limits of SCUBA diving and the contour lines of nautical charts.

History of Ecological Reserve Establishment

Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – marine protected area – Marine Protected Area was first proposed by Lester B. Pearson College in 1979. Concerned about the effect of increasing visitation and harvesting, the marine biology teacher, Garry Fletcher, and his students sought legal protection. Their goal was to ensure the preservation of marine mammals, sea birds and underwater organisms for future generations. They were assisted by Brent Cooke of the Royal British Columbia Museum, Dr. Paul Breen of the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, Dr. Derek Ellis of the University of Victoria and a host of other advisors. Garry and his students undertook 80 dives to collect data. They compiled background information to support ecological reserve – marine protected area designation including: observation records; species checklists; bottom profiles; tidal currents; salinity levels; and temperature variations. They also offered to undertake the responsibility for stewardship of the area as volunteer wardens. Their role wou be to provide information to divers and advised them of appropriate behavior. They would also continue to accumulate information and serve as assistants to researchers.

With the data collected by Lester B. Pearson College, the Race Rocks area fit the criteria for ecological reserve designation and was proclaimed under Order In Council no. 692, March 27, 1980.

The ecological reserve – marine protected area is almost entirely subtidal, but includes nine islets, comprising less than 1 ha in total. Intertidal and subtidal zones have substrates primarily of continuous rock and a rugged topography which includes cliffs, chasms, benches and surge channels. The location at the southern tip of Vancouver Island, plus the rugged shallow sea bottom, result in strong currents, eddies and turbulence.

The geology of Race Rocks is volcanic in origin, with the islets being offshore basalts. Granite and quartz intrusive, probably of the undeformed kind, are evident. Sediment basins can be found in subtidal areas.

The important oceanographic features which have a bearing on biodiversity are tides, currents, wave action, water temperature and turbidity.

Tidal currents are a major oceanographic feature of Juan de Fuca Strait. The ebb and flood tides and residual current have a major influence on the water structure. In addition, Race Rocks is a transition zone between the inner waters and the open ocean. For ebb tide that funnels water from the low-salinity, nutrient-rich waters of coastal rivers such as the Fraser and countless tidal marshes along the Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound through the narrow part of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The flood tides, that bring in water from the nutrient-rich upwellings of the open Pacific Ocean. As tidal flow surges past the rugged topography of Race Rocks results in ‘racing’ current, eddies and turbulence. Currents flow with velocities of two to seven knots and change direction according to tide, wave and wind direction. The wave action is more pronounced at Race Rocks due to the exposure to the outer portion of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The variability in undersea topography results in waves being reflect, diffracted and refracted in irregular patterns, resulting eddies and complex tides.

The water temperature is generally greater than 7∞ C with no distinct thermocline occurring. Mean surface temperatures are 7∞ C to 8∞ C in January, rising to 10∞ C to 11∞ C in August and September. In summer, the water is slightly cooler during flood than during the ebb tidal phase. Tidal flushing and turbulent currents reduce vertical layering of water masses. Surface salinity values average 31∞ /00 through the years and are characteristic of the waters in the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Water clarity is seasonally dependent, being largely determined by the phytoplankton content of the water. In the winter, low phytoplankton populations result in good underwater visibility (sometimes greater than 15 metres) except after storms. In the summer , underwater visibility lowers with increasing phytoplankton. There is no significant turbidity due to freshwater run off.

Race Rocks is subjected to strong wave action during southeasterly and southwesterly gales which are characteristic of fall and winter. A prolonged westerly storm may produce swells 3 to 4.6 m high with 1 to 3.24 m high wind waves superimposed. Southwesterly gales produce smaller swells (2.5 to 3.7 m high) because of the limited fetch available across the Strait of Juan de Fuca. During calm periods between gales and the summer, a surge is produced by the low westerly swells (1 – 1.2 m) that are present through most of the year.

Race Rocks is in the rainshadow of the Olympic Mountains and the end of the wind funnel of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Often, the ecological reserve – marine protected area experiences weather patterns quite different than southern Vancouver Island. It has an unusually high amount of sunshine the winter months, very seldom recording freezing temperatures. In summer, there is the occasional blanketing of fog.

The winds in Juan de Fuca Strait blow principally from the southeast and northwest. Outward blowing winds occur 50% of the time during the winter (October through March) while the inward blowing winds predominate during the summer (April through September).

The rich variety and abundance of seashore life of the Pacific coast is due to the nutrient-rich waters, relatively uniform seasonal range of temperature and freedom from winter icing. Excellent light penetration results in the shallow clear waters teeming with plankton. Combined with the varied topography, the ecological reserve – marine protected area has exceptional variety and productivity of marine life and tremendous ecological diversity. Intertidal, shallow water, deep water and rocky substrate ecosystems support encrusting animals and plants capable of withstanding high velocity currents. In the lee of the island, quiet water flora and fauna are extremely abundant.

The marine communities here are unusually luxuriant and rich. The “coelenterate” fauna is perhaps the richest in the world and benthic fauna is abundant and diverse. Species such as Pink Coral, Gersemia rubiformis, and Basket Seastar, Gorgonocephalus eucnemis, that are usually found at much greater depths are found here at several metres. In addition, there is an unusual abundance of ubiquitous species such as Coralline Algae, Corallina sp., and Brooding Anemone, Epiactis prolifera.

Given the nutrients, some organisms grow to a large size. For example, Giant Barnacle, Balanus nubilus, reaches sizes in excess of four inches and the Thatched Barnacle, Semibalanus cariosus, achieves a prickly texture. The occurrence of disjunct echinoderm species such as the seastar Ceramaster articus, numerous specimens of the Cup Coral, Balanophyllia elegans, the Northern Abalone, Haliotis kamtschatkana, and the Butterfly or Umbrella Crab, Cryptolithoides sp., contribute to the unusual character of the subtidal communities.

The ecological reserve – marine protected area contains an abundance of plumose and brooding anemones, Epiactis prolifera, and large numbers of sponges and ascidians. At least 65 species of hydroids, giant barnacles, a variety of colonial tunicates, three species of sea urchins, sea cucumbers, and basket stars adorn the underwater cliffs. Bright pink hydrocoral, soft pink coral, bryozoans and long-lived species of mussels are found here. Other molluscs include chitons, limpets, snails, scallops, and pacific octopus. The rare spiral white snail, Opalia sp., occurs in one limited area. The ecological reserve – marine protected area protects thriving populations of intertidal species that have been severely impacted by sports and commercial harvesting elsewhere. These include three species of sea urchins, goose-neck barnacles and the mussel, Mytilus californianus.

Twenty-two species of algae have been recorded, including extensive stands of Bull Kelp, Nereocystis luetkeana,. In the intertidal zone, over 15 species of red, brown and green algae exhibit striking algal zonation patterns, distinctive to the Pacific coast. Several species of red algae, Halosaccion glandiforme, Endocladia muricata and Porphyra sp., occupy relatively high levels on the intertidal shoreline. Porphyra sp. are particularly abundant in the early spring at higher intertidal levels. Microscopic flagellated euglenoids, Pyramonas, live in the high rock pools, giving them a bright green color. The rock walls of tide pools and the shallow subtidal areas are encrusted with the Encrusting Pink Algae, Lithothamnion sp., and large populations of coralline algae. Dead Man’s Fingers, Codium fragile, rare to this area, is found in two small isolated areas of the intertidal zone on the main island. Over 20 species live subtidally and a dense canopy of bull kelp rings all the islands and extends underwater to 12 metres.

The Surfgrass, Phyllospadix scouleri, is abundant in a narrow band near zero tide level and in the deeper tidepools on the western side of the main island.

Over fifteen hundred California Sea Lions, Zalophus californianus, and Steller or Northern Sea Lion, Eumetopias jubatus, haul out on the islets south of Great Race Rocks between months of September and May. In the spring, they tend to move out the area and head north to breed on the Scott and Queen Charlotte Islands. In recent years, 35 to 70 Northern lions and up to 800 California sea lions have used Race Rocks as a winter haul-out.

Several hundred Harbour Seals, Phoca vitulian, inhabit Southwest and North Race Rocks year round, bearing their young in June. Six to eight Northern Elephant Seals, Mirouaga angustirostris, have started to frequent the reserve. Up to 60 transient and resident Killer Whales, Orcinus orca, frequent the waters foraging on the sea lions and seals. A family of River Otters, Lontra canadensis, has also been living in the ecological reserve – marine protected area. Other marine mammals that are occasionally observed in the waters of the ecological reserve – marine protected area are Northern Fur Seal, Callorhinus ursinus, Dall’s Porpoises, Phocoenoides dalli, Gray Whales, Eschrichtius robustus, and False Killer Whales, Pseudorca crassidens.

Race Rocks serves as a nesting colony and a migration resting area. Glaucous-winged Gulls, Larus glaucescens, and Pelagic Cormorants, Phalacrocorax pelagicus, are the most abundant nesting birds in the summer months. Approximately 235 pairs of cormorants nest on the cliffs of Great Race Rock and on the southern outer island. One hundred and eighty pairs of gulls nest in the high spray zone around the perimeter of the main island and on the small outer islands. Eighty pairs of Pigeon Guillemots, Cepphus columba, nest in rock crevasses on the central island and up to 10 pairs of Black Oyster Catchers, Haemotopus bachmani, nest on the islands. Bald Eagles, Haliaeetus leucocephalus, frequent the area, with groups of 50 birds being sighted on the rocks in winter months. Harlequin Ducks, Histrionicus histrionicus, Surfbird, Aphriza virgata, Rock Sandpipers, Calidris ptilocnemis, and Black Turnstons, Arenaria melanocephala, can be observed occasionally, particularly in the winter. Brandt’s Cormorants, Phalacrocorax penicillatus, and Glaucous-winged Gulls, Larus glaucescens, are the most abundant birds in the fall and winter. Common Murres, Uria aalge, Tufted Puffins, Fratercula cirrhata, Rhinoceros Auklets, Cerochinca monocerata, Ancient Murrelets, Synthliboramphus antiquus, and Marbled Murrelets, Brachyramphus marmoratus,are occasional visitors. Lester B. Pearson College staff reported counting thirteen brown pelicans also on Race Rocks.

The islets of Race Rocks function as suitable alternate habitat for various sea birds that have been forced out of other areas due to environmental disturbances. For example, in the fall of 1974, unusually severe weather conditions off the Queen Charlotte Islands forced the ancient murrelet to frequent Race Rocks.

Decorated Warbonnets, Chirolophis decoratus, Red Irish Lords, Hemilepidotus hemilepidotus, sculpin, Kelp Greenling, Hexagrammos decagrammus, Ling Cod, Ophiodon elongatus, China Rockfish, Sebastes nebulosus, Tiger or Black Banded Rockfish, Sebastes nigrocinctus, and Copper Rockfish, Sebastes caurinus, swim in ecological reserve – marine protected area waters. Wolf Eels, (Anarhichthyes ocellatus, also inhabit the rock cervices. Salmon species pass through the area including: Pink Salmon, Oncorhynchus gorbuscha; Chum Salmon, O. keta; Sockeye Salmon, O. nerka; Coho Salmon, O. Kisutch; Chinook Salmon, O. tshawytscha.

Historical and Cultural Features

This small group of islets were known to the early sailors as the “dangerous group” . They were subsequently renamed “Race Rocks” by officers of the Hudson’s Bay Company upon the recommendation of Captain Kellet who previously noted the dangers created by the rip tides and current which raced around the islands.

Given that the rocks and reefs of Race Rocks were a danger for converging shipping traffic from Seattle, Vancouver and Victoria, the second oldest lighthouse on the southwest coast lighthouse was built on Great Race Rock. It was constructed of four-foot, cut and fitted granite blocks brought around Cape Horn from England in 1858, build in 1860 and lit on February 7, 1861. It stands 39 metres (105 feet) above the ground. The tower was automated in 1996 and no longer requires light keeper staff.

Despite the Race Rocks lighthouse and another at Fisgard at Esquimalt Harbour, by 1936 at least thirty five vessels had met with disaster in the immediate vicinity of Victoria. The “Nanette” (1860), the “Lookout” (1872), the “Sechelt” (1911), “Rosedale”, “James Griffith”, “Albion Star”, and the “Siberian Prince” are only a few of the ships which were wrecked on or near Race Rocks. Within the ecological reserve – marine protected area lie at least two shipwrecks, the “Nanette” and the “Fanny”, a sailing ship which was built in Quebec.

In 1950, the lighthouse keeper disappeared in Race Passage while trying to row to the mainland for supplies. In 1960, the Department of National Defense installed a bronze plaque on the lighthouse tower to commemorate the centennial of the lighting of this important aid to navigation.

Tenures, Occupancy Rights and Jurisdictions

Water column is in federal jurisdiction and the land, including the sea bottom, is provincial jurisdiction. Great Race Rock is excluded from the ecological reserve – marine protected area and, until recently, was administered by the federal government. With the automation of light houses, most of the island is now being transferred back to the Province. Lester B. Pearson College has a two-year agreement with the Canadian Coast Guard to occupy the site and run a research station from the outbuildings. The College has been successful in generating funding to maintain the buildings and to keep on the lighthouse keeper as a guardian until 1998. The College has applied for a license of occupation with BC Lands to continue their activities there.

The lighthouse has been designated a heritage site under the Heritage Conservation Act. With recent changes to the Heritage Conservation Act, wrecks more than two years old are protected from unauthorized removal of artifacts.

Resource Use Adjacent to Ecological reserve – marine protected area

This part of the coast is one of the most productive recreational salmon sport fishing water in British Columbia and in the past sports fishing has been a popular activity in ecological reserve – marine protected area waters. In 1990, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans closed the waters surrounding the ecological reserve – marine protected area to the commercial harvest of fin and shellfish and to recreational harvest of shellfish, ling cod and rockfish. Recreational fishing of salmon and halibut can still occur. Fishers have reported that the ecological reserve – marine protected area is not a good fishing area for salmon and that the halibut recreation fishery occurs in deeper water beyond the bounds of the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

The Naval Base in Esquimalt use the area for testing of weapons. Underwater explosions may be negatively impacting marine mammals in and around the ecological reserve – marine protected area.

Oil tankers from Alaska, freighters from Europe and Japan with industrial goods ranging from cars to forest products pass by the ecological reserve – marine protected area. Ships used to come within half a mile of the rocks but since designation of the Traffic Separation Lanes, they pass further away. Smaller vessels come close or pass through Race Passage, mainly tenders and fishing boats from Vancouver and Victoria on their way to or from the salmons and herrings grounds in the Pacific. On weekends, particularly in the summer, the surrounding waters are covered with sports fishers and small boats.

Much of the research activity in the ecological reserve – marine protected area has been undertaken or assisted by Lester B. College, for two reasons. First, the college is close by, located in nearby Pedder Bay. Secondly, the marine ecology instructor, Garry Fletcher, has used the area for educational purposes with his students undertaking many research projects and has an interest in researching the area. The light station complex on Great Race Rock provides a base and sanctuary for the researchers.

Since the establishment of the ecological reserve – marine protected area, the science students, members of the diving service and faculty of Lester B. Pearson College have continuously monitored underwater and intertidal life. They now monitor tidepools and 13 under water reference stations and have installed intertidal and subtidal reference pegs. Students have done original research on the following topics: distribution of barnacles in the intertidal zones in the different exposures; population density study on sea urchins; intertidal anemone Anthopleura elegantisima; limpets; marine mammals acoustic monitoring; Euglenoid; incidence of Imposex in carnivorous snails such as the spindle whelk (Serlesia dira); internal parasites of the Hairy Shore Crab (Hemigraspus oregonensis) and Purple Shore Crab (H. nudas); colonization in a heavy current channel; marine red algae Halosaccion glandiforme populations; and research on biotic association of Giant Barnacles with hydroid species.

The students of Lester B. Pearson College assisted Dr. Anita Brinkmann-Voss (under the auspices of the Royal Ontaria Museum) to identify 65 species of hydroids. Many of these had never been found in North America and is totally changing the classification of these animals, with a new genus and possibly even a new family. The Royal British Columbia Museum has done research on nesting seabirds. Other researchers have studied transient Orca whales, seals and sea lions. Research on northern abalone (Haliotis kamschatkana) as an indicator species for ‘No Take’ marine protected areas was completed in 1997 by Scott Wallace.

Daily water temperature since 1927 and salinity records since 1936 of the surrounding waters have been taken by the staff of the light station. Water currents were monitored by instruments from the Institute of Ocean Sciences with assistance of Lester B. Pearson College in the early 1980s. The present Race Passage Current tables are a result of that research.

Since the late 1970s, Lester B. Pearson College has been using the ecological reserve – marine protected area as an education facility for courses on biology and environmental systems. In addition, they lead school tours in the spring and fall. Up to 150 grade seven students from local schools either visit Great Race Rock for ecology work in the spring. The objectives of this school program are: to gain a first hand experience on the complex marine systems; to instill a respect for marine life and concern for its conservation; and, to develop an appreciation for ecological reserve – marine protected areas. The children often get a tour of the light station, and are introduced to intertidal and subtidal marine life.

Education has been enhanced through live telecasts in the Underwater Safari series, which continue to be broadcast. This experiment in real-time video access for one week in 1992 showed the potential for using technology to provide access electronically to thousands of viewers without impacting the integrity of this sensitive ecosystem. This has raised awareness globally on the “Adopt an Ecosystem” approach.

The Internet is another means of education. In 1995, Lester B. Pearson College established a world wide web page with information on Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area and their activities there. This has raised awareness globally.

Generally, there are three categories of visitors to the ecological reserve – marine protected area: 1) boaters who are primarily observing the marine life around the rocks, particularly marine mammals; 2) boaters who come ashore, usually to visit the lighthouse facilities; 3) divers who dive either from shore or from boats. Visitation to the ecological reserve – marine protected area has been increasing, particularly those engaged in whale watching and diving. Concerns are being raised about the affects on visitation on the whales and their foraging activities. Uncontrolled, and unrestrained pursuit of the whales could interfere with behaviors and ability of the whales to feed in this area.

Dive tours are also increasing. Uncontrolled use of the ecological reserve – marine protected area could result in increasing in poaching of sea life, physical injury and mortality from handling and improper dive techniques. These could lead to impacts on the underwater life, for which the ecological reserve – marine protected area is to protect.

Management Considerations

Management of Recreation and Commercial Activities

Activities such as whale watching, commercial diving, boating and nature appreciation occurs in the ecological reserve – marine protected area, both in the water and on land. Activities, their types, and levels of use require management to ensure that values of the ecological reserve – marine protected area are maintained.

Management of Research Activities and Facilities

Race Rocks is well-known and well-used for research purposes, as a result of the efforts of Lester B. Pearson College. The college undertakes and assists with most of the research .

Cooperation with the Federal Government

The ecological reserve – marine protected area legislation pertains only to the foreshore and the land under the water column. The water column, which is an important component of the ecological reserve – marine protected area, actually under Federal jurisdiction.

Cooperation with Lester B. Pearson College

Lester B. Pearson College plays a large role in the management and the research undertaken in the research. Garry Fletcher and his students have been the wardens of the ecological reserve – marine protected area since its creation. They work closely with school groups, naturalist groups, divers and other researchers who visit the ecological reserve – marine protected area, providing information on appropriate conduct and guiding services. With their plans to set up and staff a research centre on Great Race Rock, they could provide an even greater monitoring role.

Ecological reserve – marine protected area Boundary

The 220 hectares of the ecological reserve – marine protected area include an area of ocean, nine small islands and reefs bounded by the 36.6 metres contour. This boundary is difficult to mark and enforce.

Management of Educational Activities

Lester B. Pearson College uses Race Rocks Ecological Reserve – Marine Protected Area for their marine ecology program involving college, local school students, and naturalists. Tourism operators from Victoria also offer natural history tours of the area.

Management of Ecological reserve – marine protected area Values

Sewage disposal on Great Race Rocks, fishing in the ecological reserve – marine protected area for salmon and halibut, military testing and the potential for oil spills are issues that exist on this site.