Marine Protected Areas

A Strategy for Canada’s Pacific Coast

Marine protected areas are a vital part of our commitment to sustainable economies, viable coastal communities, and a healthy, diverse marine environment. Our goals are to protect and conserve the natural beauty and richness of our marine areas, to maintain ecological diversity, and to preserve the many recreational, natural and cultural features of our Pacific coastline for all time.

DISCUSSION PAPER August 1998

A Joint Initiative of the Governments of Canada and British Columbia

Foreword

On behalf of the governments of Canada and British Columbia we are pleased to present this discussion paper, “Marine Protected Areas, A Strategy for Canada’s Pacific Coast“. The Pacific coast of Canada is one of the most diverse and productive marine environments in the world – we rely on it in many ways, as a source of food,employment, recreation and spiritual renewal. We want to build and protect this richness for present and future generations. Our commitment to a Marine Protected Areas Strategy isa key piece of the foundation for this goal.

This Strategy has been developed jointly by federal and provincial agencies and clearly reflects the need for governments to work in unison to achieve common marine protectionand conservation goals. The Strategy is not a new program, but an initiative to coordinate all existing federal and provincial marine protected areas programs under a singleumbrella. This will allow for the development of a national system of marine protected areas on the Pacific coast by the year 2010 which is interlinked with the marine componentof the B.C. Protected Areas Strategy.

This discussion paper reflects extensive advice and feedback from our resource agency staff, as well as local governments, First Nations, and community, stakeholder andindustry perspectives. We now want to provide all marine interests and users an opportunity to review and comment further on the Strategy.

We are pleased that Canada and British Columbia are able to release this paper in 1998-the International Year of the Ocean. The success of conserving and protecting naturalmarine areas is a shared responsibility, we look forward to working with you to complete a “Marine Protected Areas Strategy for Canada’s Pacific Coast“.

Signed by Donna Petrachenko (Director-General, Pacific Region – Department of Fisheries and Oceans) Co-chair, MPA Strategy Steering Committee

Signed by Derek Thompson (Assistant Deputy Minister – British Columbia Land Use Coordination Office) Co-chair, MPA Strategy Steering Committee

Table of Contents

1.0 Introduction

The Pacific coast is host to a multitude of ecological, social, cultural and economic values which provide benefits and opportunities for all who have the good fortune to enjoyour spectacularly beautiful maritime coastline. Few people know that our coast is also among the most biologically productive in the world and continues to generate tremendouswealth for British Columbians and Canadians.

We have recognized that the sustainability of the world’s oceans is increasingly becoming a critical concern to coastal nations. The need to maintain the health andvitality of our marine resource base, together with broad ranging global issues such as continued urbanization of coastal areas, pollution, habitat alteration and loss, and overexploitation, are key concerns. These problems and opportunities are fueling our desire to establish a system of marine protected areas along the Pacific coast of Canada as oneessential tool to address the needs of our oceans.

The MPA Strategy proposes three important elements:

- A joint federal-provincial approach: All relevant federal and provincial agencies will work collaboratively to exercise their authorities to protect marine areas.

- Shared decision-making with the public: Commits government agencies to employ an inclusive, shared decision-making process with marine stakeholders, First Nations, coastal communities, and the public.

- Building a comprehensive system: Seeks to build an extensive system of protected areas by the year 2010 through a series of coastal planning processes.

The benefits of marine protected areas are many, and include:

- contributing to the protection of the structure, function and integrity of ecosystems;

- encouraging expansion of our knowledge and understanding of marine systems;

- enhancing non-consumptive and sustainable activities; and,

- improving the health of our ocean resources.

A total of 104 marine protected areas on the Pacific coast have already beenestablished. These were put into place using a variety of legislative tools and they consist predominantly of relatively small marine parks, ecological reserves and wildlifemanagement areas created to meet specific conservation and recreation needs. In the past, the need to work in collaboration to reach mutual goals was not apparent, and the majorityof protected areas were created by individual federal and provincial agencies operating on their own.

Central to this Strategy are a number of coastal planning processes which would be undertaken by governments over time throughout six major coastal regions (see Section5.2). These planning processes are inclusive and collaborative, in order to involve everyone with an active interest and to ensure that general and specific uses of coastaland marine areas, including Marine Protected Areas, are addressed.

For example, as part of the coordinated planning approach, Canada and B.C. signed an agreement in 1995 called the Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy (PMHL), which has as itscentral vision the creation of a system of marine and coastal protected areas along the entire Pacific coast. The current focus of the PMHL is the acquisition of land in thesouthern Gulf Islands and the consideration of a complementary Marine Conservation Area in the Gulf Islands’ encompassing waters.

To date, a federal-provincial government Working Group and senior management Steering Committee have been working to develop this Strategy discussion paper. However, broaderpublic involvement and acceptance is needed and will be essential to the success of the Strategy. This paper provides readers with an overview of the proposed Strategy andinvites comments. Section 6.0 in particular poses specific questions to which we are seeking your comments.

2.0 What are Marine Protected Areas

“Marine protected areas” are sites in tidal waters that enjoy some level of protection within their respective jurisdictions, although internationally the term may bedefined and interpreted quite differently from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. For example, the World Conservation Union uses it as a generic label for protected marine areas such assanctuaries, parks, reserves, harvest refugia and harvest replenishment areas. Under the new Canada Oceans Act, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has authority to formally designate Marine Protected Areas, however, in this discussion paper, we have agreed to usethe term broadly to describe all the federal and provincial designations that protect marine environments.

Sidebar #1: What are Marine Protected Areas

Marine Protected Areas could include:

-unique coastal inlets, bays or channels;

-representative marine areas;

-boat havens with important anchorages;

-marine-oriented wilderness areas;

-cultural heritage features;

-critical spawning locations and estuaries;

-species-specific harvesting refugia;

-foraging areas for seabird colonies;

-summer feeding and nursery grounds for whales;

-offshore sea mounts or hydrothermal seavents; and

-a host of other special marine environments and features.

Regardless of the particular designation, all marine protected areas (MPAs) under the Strategy would:

1. Be defined in law

The legal authority to establish an MPA will derive from one of several federal and provincial statutes including: Canada’s Oceans Act, Fisheries Act, National Parks Act, Canada Wildlife Act, Migratory Birds Convention Act, or proposed Marine Conservation Areas Act; and British Columbia’s Ecological Reserve Act, Park Act, Wildlife Act or Environment and Land Use Act.

2. Protect all or a portion of the elements within a particular marine environment

The federal and provincial governments have differing and, at times, overlapping jurisdiction in marine areas. Depending upon the statute under which an MPA is created,the area may comprise any combination of the overlying waters, the seabed and underlying subsoil, associated flora and fauna, and historical and cultural features.

3. Ensure Minimum Protection Standards

All MPAs would share Minimum Protection Standards prohibiting:

- ocean dumping;

- dredging; and,

- the exploration for, or development of, non-renewable resources.

Building on these minimum protection standards, the system of MPAs will accommodatemultiple levels of protection. Levels of protection provided by an MPA will vary depending upon the objectives for each site. For example, MPAs may be highly protected areas thatsustain species and habitats; areas that are established primarily for recreational use or cultural heritage protection; or multiple use areas that balance resource conservationwith recreational and other activities such as commercial and sport fishing. Even within a particular MPA, levels of protection may vary through the use of zoning specifyingpermissible activities for sub-areas.

Establishing a system of MPAs is only one part of an integrated approach to oceans management, but it is an essential one. MPAs help conserve the ocean’s life-givingservices, species and habitats to ensure that our coastal resources can continue to support present and future generations. The intent of MPAs is not to take anything away. Quite the opposite. MPAs can contribute to the restoration and conservation of marineresources for people whose livelihoods depend on harvesting. As well, they can support a wide range of recreational and aesthetic values, providing a win-win for all. Perhaps mostimportantly, they will help us to protect the quality of life we cherish. They are an insurance policy for our future.

Sidebar #2: Marine Protected Areas in a Global Context

The establishment of MPAs now occurs in many coastal nations around the world. While still less numerous than terrestrial protected areas, more than 1,300 MPAs have beencreated worldwide. MPAs have gained a high level of acceptance as a tool to help achieve the conservation of marine biodiversity, the sustainability of commercial and sportfisheries, and the viability of coastal communities that depend upon them.

Early efforts in the evolution of MPAs as a management tool took place mostly in tropical and sub-tropical waters-in the Florida Keys in 1935, in Australia’s Great BarrierReef in 1936, the Philippines in 1941, the Bahamas in 1958 and Mexico in 1960. Still today, most MPAs around the world have been established in these warmer marineenvironments, focusing on such important features as coral reefs, seagrass habitats and coastal mangroves. Temperate waters such as Canada’s have not been the subject of the samelevel of conservation efforts and the high levels of public awareness that, for example, the Great Barrier Reef generates.

B.C. has been the most active of Canadian provinces in the establishment of MPAs. The designation in 1925 of Glacier Bay National Park in Alaska may be the only MPA in theworld’s temperate waters to predate B.C.’s first marine parks at Montague Harbour and Rebecca Spit in 1957. Many of these early marine parks in B.C. were small, protectinganchorages and scenic shoreline areas important to recreational boaters. Beginning in the 1960s, and continuing through the 1970s and 1980s, however, the world began to recognizethe merits of MPAs as management tools for conservation, as well as for recreation, and called for the establishment of larger and more conservation-oriented MPAs. B.C. andCanada responded with the creation of new and larger areas such as Desolation Sound Provincial Park, Pacific Rim National Park Reserve (half of which is waters of the openPacific Ocean), and Checleset Bay Ecological Reserve.

Today, B.C. and Canada manage 104 MPAs, totaling about 1955 square kilometres. In addition, Canada is in the process of establishing the 3050 square kilometres Gwaii HaanasNational Marine Conservation Area in the southern Queen Charlotte Islands

3.0 The Need to Create Marine Protected Areas

The motivation to protect marine areas derives from a widespread appreciation of the beauty and bounty of the world’s oceans in the face of numerous pressures now affectingits health and stability. Largely a consequence of human activities, the serious stresses placed upon our oceans globally have given rise to calls for coastal nations to makeconservation and preservation of marine biodiversity and ecosystems a worldwide priority. This is the strongest message in the United Nations initiative to declare 1998 as theInternational Year of the Ocean.

3.1 Values of Canada’s Pacific Marine and Coastal Environments

With more than 29,500 kilometers of coastline, 6,500 islands and approximately 450,000 square kilometres of internal and offshore waters, the marine and coastal environments of Canada’s Pacific coast have an impressive variety of marine landforms, habitats and oceanographic phenomena that accommodate a broad range of species diversity. Island archipelagos, deep fjords, shallow mudflats, estuaries, kelp and eel grass beds, strong tidal currents and massive upwellings all contribute to an abundant and diverse assemblage of species.

The Pacific coast of Canada is one of the most spectacular and biologically productive marine and coastal environments of any temperate nation in the world. The northeastPacific represents a significant and varied collection of marine invertebrates comprised of more than 6,500 species. In the vertebrate family, there are 400 fish species, 161marine birds, 29 marine mammals, and one of the world’s largest populations of orcas; there are nesting grounds for 80 percent of the world’s population of Cassin’s auklet, and wintering grounds for 60 – 90 percent of the world’s Barrow’s goldeneye; as well, the region boasts of the world’s heaviest recorded sea star, and largest octopus, sea slug,chiton and barnacle.

Recognized as a spectacular and productive marine and coastal region, the northeast Pacific contributes significantly to B.C.’s economy and strongly influences the cultureand identity of its residents. It is estimated that the Pacific marine environment contributes up to $4 billion annually to the coast’s economy. In addition, one in everythree dollars spent on tourism in B.C. goes toward marine or marine-related activities.

B.C.’s marine regions also contain a rich cultural history. For the First Nations peoples who have lived along the shores for thousands of years, many coastal areas remainimportant for food, social, ceremonial, and spiritual purposes. The cultural history of the Pacific coast is further illustrated by numerous physical relics of the past, such asship wrecks and whaling stations.

As well, a vast array of recreational opportunities are available in coastal areas. For example, the Inside Passage is one of the most popular cruising and sailing destinationsglobally, and kayakers are attracted to the numerous archipelagos peppered along the coast. In a recent divers survey, British Columbia’s coast was rated as the best overalldestination in North America, even when compared to such tropical destinations as the Florida Keys, the Gulf of Mexico and southern California.

Some of these significant ecological, cultural, and recreational values are already protected in MPAs along the B.C. coast. Much of the current system has, however, beenestablished in an ad hoc manner with an emphasis on near-shore environments. The result is that many marine values and ecosystems remain underrepresented, and the levelsof protection both between and within protective designations vary significantly.

3.2 Threats to Marine Ecosystems

1. Physical alteration of critical habitat and marine areas

The alteration, deterioration or degradation of habitat has a significant impact on marine ecosystems. Habitats may be damaged through actions such as dredging and filling,trawling, anchoring, trampling and unauthorized visitation, noise pollution, siltation from land based activities, and altered freshwater inputs. Most habitat loss in B.C.occurs in estuaries and nearshore areas, but deeper areas can also be affected by ocean dumping. A primary concern in B.C. is the degradation and loss of eelgrass habitat, whichis important for numerous fish and shellfish species as part of their life cycles.

2. Excessive harvest of resources

History has clearly shown that the productive capacity of the seas and their ability to deliver resources to the needs of humankind are limited. In addition to the economic andsocial consequences of the excessive harvest of many fish and shellfish species, there are other ecological consequences. Recent research has suggested that around the world marineresource harvesting is altering the natural cycle of marine food webs. The continuation of this trend could result in serious implications for people who depend on the oceans’resources.

3. Pollution

While the water quality along Canada’s Pacific coast is generally considered to be quite good, there are many area specific concerns. These sources of pollution may includeindustrial and municipal wastewater discharges, agricultural runoff, the dumping of dredged materials, and the threat of oil and chemical spills. To date there has been nocoast-wide assessment of marine environmental quality, and no data exist on either the current status of or long term trends for water quality. One indicator of water quality -the number of shellfish closures – has risen along the B.C. coast to about 160 per year. This covers an area of approximately 100,000 hectares.

4. Foreign or exotic species of fishes and marine plants

The introduction of foreign or exotic marine species has altered the composition of many biological communities on the Pacific coast. Large areas of mudflat have beencolonized by an introduced eelgrass, rocky shorelines in the Strait of Georgia are often covered in introduced oysters, and one of the more common clams – the soft shell clam -has also been introduced. While some of these impacts occurred as far back as the turn of the century, others are still happening, such as the recent northward expansion of thegreen crab towards B.C.’s waters.

5. Global climate changes

Although the mechanisms driving long term climatic variations are complex, and the role of human activities in these changes has not been established, these fluctuations have alarge impact on the kinds and nature of species found in B.C.’s waters at any particular time. For example, during the past 1997/98 El Nino event, species usually found only inwarmer waters migrated northward into B.C.’s waters, where in many cases they consumed large numbers of local species.

4.0 Vision and Objectives for a Marine Protected Areas Strategy on Canada’s Pacific Coast

4.1 The MPA Vision

Generations from now Canada will be one of the world’s coastal nations that have turned the tide on the decline of its marine environments. Canada and British Columbia will haveput in place a comprehensive strategy for managing the Pacific coast to ensure a healthy marine environment and healthy economic future. A fundamental component of this strategywill be the creation of a system of marine protected areas on the Pacific coast of Canada by 2010. This system will provide for a healthy and productive marine environment whileembracing recreational values and areas of rich cultural heritage.

Along the coast of British Columbia, comprehensive coastal planning processes will be undertaken, ensuring ecological, social and economic sustainability. These processes willprovide the mechanism for establishing an MPA system and ensuring a holistic, inclusive and multi-use approach to resource use and marine management.

This is the vision behind the MPA Strategy, a future that can be realized through a cooperative and integrated process, and by a step-by-step commitment to the key objectivesoutlined below.

4.2 Objectives for Establishing Marine Protected Areas

MPAs will serve a range of functions and exist in a wide array of sizes, shapes, and designs. They are an important conservation tool that, when used in conjunction with othermanagement applications, can result in many benefits for coastal communities, tourists, and regional and national economies. Under this proposed Strategy, the establishment of asystem of MPAs would serve six objectives:

1. To Contribute to the Protection of Marine Biodiversity, Representative Ecosystems and Special Natural Features

MPAs can contribute to the maintenance of biodiversity at all levels of the ecosystem, as well as protect food web relationships and ecological processes. They give refuge tovulnerable species thus helping to maintain species presence, age, size distribution and abundance; they protect endangered or threatened species, preventing species loss; andthey preserve the natural composition and special natural features of the marine community.

Biodiversity is the variability among living organisms and the living complexes of which they are a part. It is expressed in the genetic variability within a species(such as different stocks of the same species), in the number of different species (e.g., 36 species of rockfish on the Pacific coast), and in the variety of ecosystems andhabitats along the coast (such as different plant and animal communities that appear with increasing water depth).

Representative ecosystems have been identified on Canada’s Pacific coast through the use of ecological classification systems. Parks Canada has identified Marine Regionsat the national level to plan the system of Marine Conservation Areas. At a more refined level, the B.C. government has identified 12 marine ecoregions with 65 sub-componentecounits. Both classification systems will help guide the planning of the system of MPAs to ensure it is highly representative of the diverse marine environments found on thiscoast.

Special natural features are elements of the environment that are rare, outstanding or unique. These areas may include stopover sites for certain migratingspecies, areas with rare and unique capabilities for maintaining early-life stages of important fish and shellfish species, and habitats of high biodiversity, such as estuariesor upwelling areas. While many of these elements may be captured within large, representative MPAs, it is also necessary to specifically identify and protect special,and often site-specific, features.

2. To Contribute to the Conservation and Protection of Fishery Resources and Their Habitats

Conserving and protecting fish stocks is critical for the sustainability and stability of many B.C. coastal communities. As a result, stakeholders are keenly interested in theimplications of MPAs for all fisheries, whether First Nations,, recreational, or commercial.

Studies of marine protected areas in temperate waters indicate that they can increase population size, increase average individual fish size, lead to the restoration of naturalspecies diversity, and increase population reproductive capacity. Studies also indicate that subsequent spillover benefits to harvested areas outside and adjacent to closed areasoften occurs.

MPAs can help maintain viable marine species populations and support the continuation of sustainable fisheries by:

- Providing harvest refugia

- Protecting habitats, especially those critical to lifecycle stages such as spawning, juvenile rearing and feeding

- Protecting spawning stocks and spawning stock biomass, thus enhancing reproductive capacity

- Protecting areas for species, habitat, and ecosystem restoration and recovery

- Enhancing local and regional fish stocks through increased recruitment and spillover of adults and juveniles into adjacent areas

- Assisting in conservation-based fisheries management regimes

- Providing opportunities for scientific research

3. To Contribute to the Protection of Cultural Heritage Resources and EncourageUnderstanding and Appreciation

Cultural resources are works of human origin, places that provide evidence of human activity or occupation, or areas with spiritual or cultural value. Some examples arearchaeological sites, shipwrecks, or cultural landscapes. Terrestrial cultural resources have traditionally had more meaning than marine cultural resources because they tend to bemore evident and observable. Yet thousands of years of human occupation, including original First Nations cultures and early European contact and settlement are representedin the marine environment. MPAs can protect this rich cultural marine heritage and preserve First Nations traditional use and practices.

4. To Provide Opportunities for Recreation and Tourism

MPAs can support marine and coastal outdoor recreation and tourism, as well as the pursuit of activities of a spiritual or aesthetic nature. The protection of specialrecreation features, such as boat havens, safe anchorages, beaches and marine travel routes, as well as the provision of activities such as kayaking, SCUBA diving, and marinemammal watching will help to secure the wealth and range of recreational and tourism opportunities available along the coast.

5. To Provide Scientific Research Opportunities and Support the Sharing of Traditional Knowledge

Scientific knowledge of the marine environment lags significantly behind that for the terrestrial environment which can affect the ability of marine managers to identify themerits of protection or management options. MPAs provide increased opportunities for scientific research on topics such as species population dynamics, ecology and marineecosystem structure and function, as well as provide opportunities for sharing traditional knowledge.

6. To Enhance Efforts for Increased Education and Awareness

Over the last few years, public understanding and awareness of marine environmental values and issues have been increasing. There is general recognition that proactivemeasures are necessary to protect and conserve marine areas to sustain their resources for present and future generations. However, there is still a significant need for publiceducation to instill greater awareness of the role everyone can play in the conservation of marine environments. Many MPAs will afford unique opportunities for public educationbecause of their accessibility and potential to clearly demonstrate marine ecological principles and values.

5.0 Developing a System of Marine Protected Areas

Sidebar #3: Guiding Principles for MPA Development

1. Working With People

The federal and provincial governments will work in partnership with First Nations, coastal communities, marine stakeholders and the public on MPA identification,establishment and management.

2. Respecting First Nations and the Treaty Process

Canada and B.C. consider First Nations’ support and participation in the MPA Strategy as important and necessary. Both governments will ensure and respect the continued use ofMPAs by First Nations for food, social and ceremonial purposes and other traditional practices subject to conservation requirements. Therefore, MPAs will not automaticallypreclude access or activities critical to the livelihood or culture of First Nations. The establishment of any MPA will not preclude options for settlement of treaties, and willaddress opportunities for First Nations to benefit from MPAs.

3. Fostering Ecosystem-Based Management

An ecosystem-based approach to management requires that the integrity of the natural ecosystem and its key components, structure and functions are upheld. This meansmaintaining natural species diversity and protecting critical habitats for all stages in species life cycles.

4. Learning-By-Doing

A key aspect of Canada and B.C.’s commitment to establishing MPAs is the concept of using a learn-by-doing approach. Both governments recognize that the process for MPAplanning should evolve and improve over time given the variations between coastal regions, the dynamics of a marine environment, and the information constraints concerning marinespecies, processes and ecosystems. Flexibility and adaptability will be required to meet effectively and efficiently the needs of all marine resource users.

5. Taking a Precautionary Approach

Taking a precautionary approach means, “When in doubt, be cautious.” This principle puts the burden of proof on any individual, organization or government agencyconducting activities that may cause damage to the marine ecosystem.

6. Managing for Sustainability

The MPA Strategy is intended to contribute to sustainability in our marine environments. This means that resources in areas requiring protection must be cared for inthe present so that they exist for future generations. In the marine environment, emphasis will be placed on maintaining viable populations of all species and on conservingecosystem functions and processes.

5.1 The Coastal Planning Framework

It is proposed that a network of MPAs would be developed through coastal planning processes carried out at a number of different levels. These may range from comprehensiveprocesses that plan for a wide variety of resource uses and activities, to processes which focus on planning for very specific purposes or for the resolution of defined issues.Regardless of the level of planning for MPAs, public participation will be a fundamental component of all processes, with the principles of openness and inclusiveness forming thebasis.

This approach would enable the collaboration of all governments, including First Nations, as well as stakeholders, advocacy groups, communities and individuals in theidentification of important marine values and areas that warrant consideration for MPA status. We are seeking a commitment from everyone who has an interest to work together toestablish a system of MPAs for Canada’s Pacific coast.

The coastal planning processes are to be collaborative planning efforts, consistent with both the federal objectives for Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) andprovincial objectives for coastal zone planning.

The establishment of a complete MPA system on the coast would be largely dependent on the rate at which planning processes occur, but a basic system is intended to be in placeby the year 2010.

5.2 Planning Regions for Marine Protected Areas

For the purposes of establishing an MPA system, six planning regions have been identified, reflecting the variety of oceanographic conditions, coastal physiography,management issues, and communities along Canada’s Pacific Coast (illustrated in Sidebar #4):

1. The North Coast

2. The Queen Charlotte Islands

3. The Central Coast

4. The West Coast of Vancouver Island

5. The Strait of Georgia

6. The Offshore

A coastal planning process is already underway for the Central Coast region. The Strait of Georgia region has also been identified as a priority for such processes, and a numberof initiatives are currently being undertaken or planned, such as the Georgia Basin Ecosystem Initiative and a Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy commitment to assess thefeasibility of establishing a Marine Conservation Area in the southern Strait of Georgia.

Sidebar #4: Proposed Marine Protected Area Planning Regions and Pilot Sites for Canada’s Pacific Coast

5.3 Federal-Provincial Coordination for Marine Protected Areas Establishment

To date a federal-provincial government Working Group and senior management Steering Committee have been working together to develop the MPA Strategy. To build on theseexisting working relationships and to solidify our commitment to federal – provincial collaboration we are proposing to ensure a coordinated approach to implementing the MPAStrategy via the establishment of an inter-governmental coordinating body.

This coordinating body would 1) provide policy, program advice, and interpretation to stakeholders and the public involved with MPAs and coastal planning processes, 2) overseepublic communications on program and policy issues, and 3) manage a joint, central system for tracking and monitoring the MPA program. It would support existing planning processeswhen required, and develop a standard analytical process to guide all MPA assessment work to ensure a consistent approach and achievement of the Strategy’s objectives. In areaswhere planning is not anticipated in the short term, this body would ensure a coordinated approach to the identification and assessment of candidate MPAs, and review requests forthe application of interim management guidelines for MPA candidates. Subject to public endorsement of this body, a specific Terms of Reference would be developed.

Sidebar #5: Interim Management Guidelines

Interim management guidelines may be applied to MPA candidates under exceptional circumstances where it has been demonstrated that they are necessary to protect specificmarine resources, habitats or values that may be under threat until coastal planning is completed. Any interim management guidelines instated would remain in place until MPAestablishment decisions have been made. Governments have various measures available for providing interim protection of marine resources and habitats, such as regulations underthe Fisheries Act and the deferment of granting tenures, permits or other rights to occupy or utilize certain sites. In addition, on an emergency basis, an MPA can beimmediately declared under the Oceans Act for a maximum-but renewable-period of 90 days.

Requests for the application of interim management guidelines may originate from the MPA proponent in areas where planning is not anticipated for the short term, or from thecoastal planning process participants in planned areas. Such requests would be reviewed by both levels of government for decision-making.

5.4 MPA Identification, Assessment and Recommendation

Step1: The Identification of MPA Candidates

The first step in establishing a system of MPAs would be to identify candidate areas that reflect important or key marine values, attributes or features. MPA candidates may benominated and presented to the technical teams supporting each planning process within their associated time-frames. Planning process participants would normally includegovernment agencies, First Nations, marine stakeholders, community groups, academic institutions or individuals.

Step 2: Assessment of MPA Candidates

Candidates would be assessed according to the objectives of the MPA Strategy. Criteria for the assessment, as listed in Sidebar #6, have been assembled from the federal andprovincial agency programs for protecting marine areas. The standards to be met would reflect the intended purpose of the MPA candidate as well as unique characteristics thatmight distinguish it.

Candidate MPAs would be considered within the context of all marine resource uses and activities along the coast and in the offshore. Participants in coastal planning processeswould review the results of MPA assessments and conduct any further research necessary-such as feasibility or socio-economic impact studies-in order to make theirrecommendations.

For example, in the coastal planning process now underway in the Central Coast, a multi-agency technical team will be receiving MPA candidate proposals from processparticipants, area residents, and from interested stakeholders directly. These candidates will then be assessed by the team according to MPA objectives and criteria and then byplanning participants in the context of other resource values and uses, MPA criteria, and environmental, social and economic objectives.

Step 3: Recommendations for MPA Designation

Recommendations for MPAs would be developed on the basis that the chosen candidates are both consistent with the objectives of the MPA Strategy and complementary to the range ofother coastal and marine uses and activities being considered under an existing planning process.

In areas where a comprehensive planning process is not underway, MPAs may be assessed and recommended through the application of a tailored MPA planning process. This approachwould be limited in use and applied only in certain situations, such as where there are pressing federal or provincial priorities or major gaps in the MPA network. Consistentwith the MPA Strategy Guiding Principles, public participation will be a fundamental component of both comprehensive and tailored planning processes, employing the principlesof inclusive, shared decision making.

Step 4: Decision-Making for MPAs

Recommendations would be reviewed by governments for decision-making. It may be necessary to undertake subsequent analyses or additional studies or approve therecommendations and proceed with the establishment of the MPA.

Legal designation formalizes the management authority, the geographic boundaries for the marine protected areas, and a broad description of acceptable or permissible uses. Insome cases, a marine protected area may have deliberately overlapping federal and provincial designations, depending on its location and the level of protection required.

Step 5: Management Plans for MPAs

The agency supporting the designation of a MPA would be responsible for developing and implementing a management plan. The management plan – consistent with the approvedplanning process recommendations – would clearly define the purpose of the marine protected area; its goals and objectives, and how the goals and objectives are to bereached. similarly, the management plan will provide the detailed terms and conditions around “where” “what” and “when” permissible uses can occur.

Management plans will be subject to periodic review. Reviewing the management plan for existing MPAs would provide an important opportunity to periodically assess theeffectiveness of the management regime in place, and to revise protection levels accordingly.

5.5 Pilot Marine Protected Areas

Adhering to the learn-by-doing principle, several pilot MPAs have been identified to test and explore a number of applications including: partnering and cooperative managementopportunities and mechanisms; criteria for evaluating proposed MPAs; and coordination among agencies or governments involved in the development of the MPA Strategy.

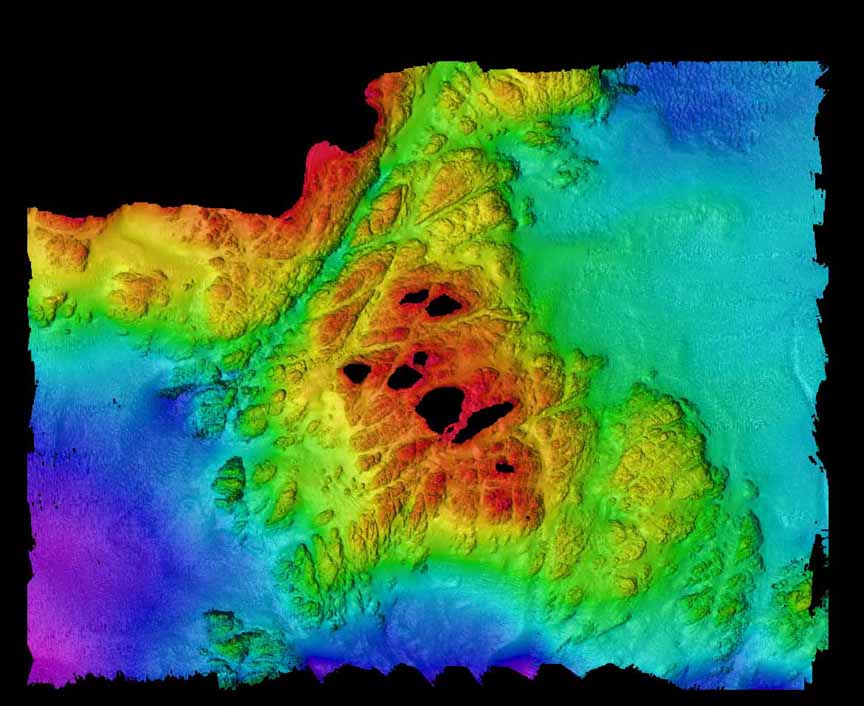

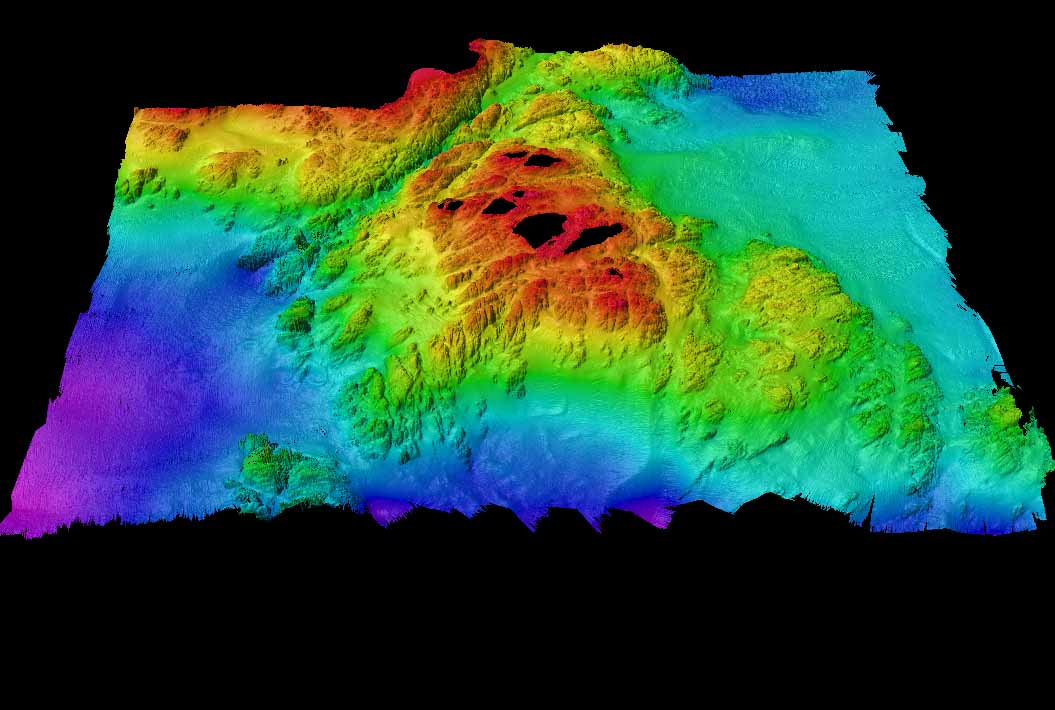

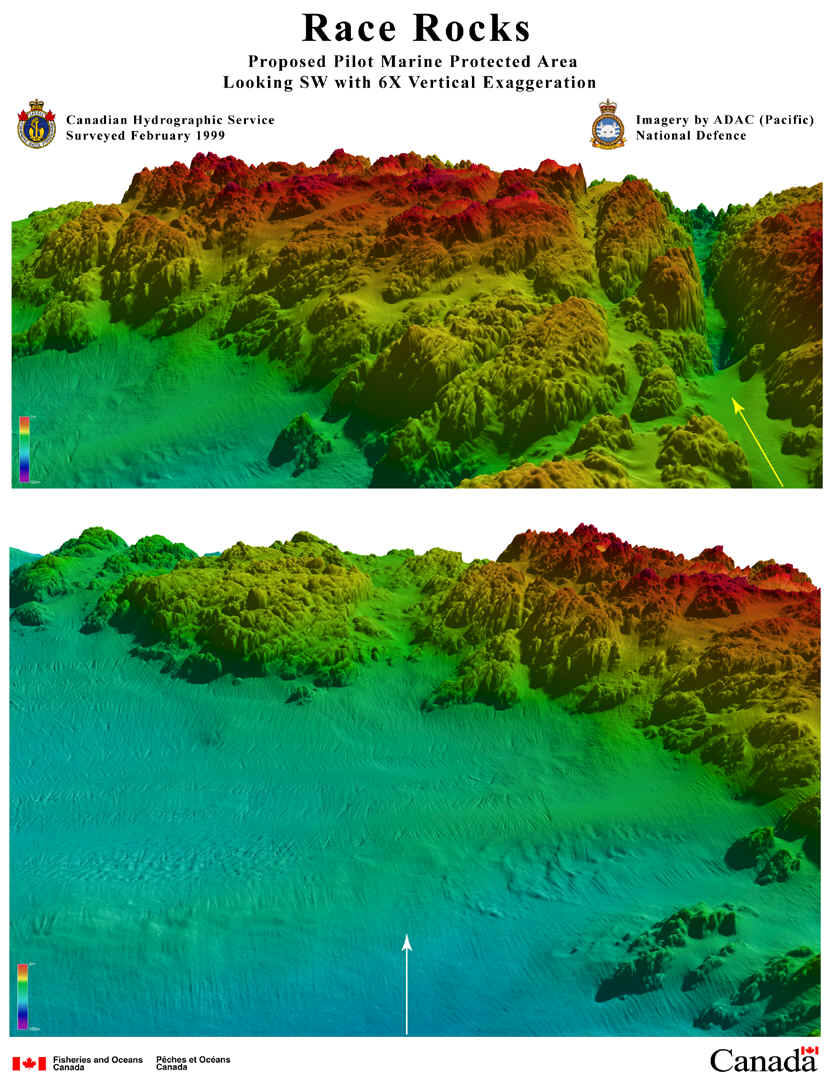

Areas that have been proposed as pilot MPAs include Gabriola Passage, Race Rocks Ecological Reserve (which is already formally designated as an Ecological Reserve), theBowie Seamount and the Endeavour Segment Hydrothermal Sea Vents. (see Map)

For several of these sites, stakeholder consultation is underway. Gabriola Passage has been subject to detailed study and consultation, but a few outstanding issues have yet tobe resolved. First Nations involvement will be considered very important to moving forward in this area. For Race Rocks Ecological Reserve, consultation is already underway througha management planning process.

Criteria used in selecting these areas as pilot projects included the following:

- level of existing stakeholder and/or community support;

- ecological, recreational and/or cultural heritage value;

- information availability;

- potential for building education and awareness; and,

- opportunities for research and monitoring.

The primary goal for pilot projects is to provide an opportunity to learn and testdifferent applications of MPA identification, assessment, legal designation, and management. Upon completion and evaluation of the pilots, formal designation may or maynot occur depending on the desire of local communities and First Nations, as well as stakeholders and the public. Throughout the MPA piloting process, opportunities will beprovided for public review and input.

In addition to these proposed pilot MPAs, both governments will be acting on their commitment in the Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy to study the feasibility of establishinga marine conservation area in the southern Strait of Georgia.

5.6 A Question of Targets – How Much is Enough?

There are varying views on the need for targets. As our knowledge of the marine realm greatly lags behind our knowledge of terrestrial environments, there is a need todetermine if MPA targets are appropriate, and if they are, then what they should be. There have been several attempts at designing measures to assess MPA targets both in B.C. and inother parts of the world, which include:

- targeting a set number of MPAs per planning region;

- targeting a percentage of area in each planning region;

- setting a target of a minimum of one relatively large “representative” MPA for each planning region (for example Parks Canada has used this approach for Marine Conservation Areas);

- targeting MPAs to protect representative areas of each habitat, ecosystem, or community type (B.C. has used this model for its terrestrial Protected Areas Strategy);

- using the best available science to determine protection requirements; and,

- not setting firm standards and limits for what needs to be protected and how much protection is required

We are seeking your advice on this important question.

5.7 Federal and Provincial Statutory Powers to Protect Marine Areas

Extensive legislative authorities already exist among the federal and provincial agencies to implement a comprehensive system of MPAs. These tools complement each otherand represent the various sources of constitutional and legislative powers necessary to enable us to work together to achieve the objectives of the MPA Strategy.

This federal-provincial partnership is essential since jurisdictional responsibilities in the marine environment are shared. For example, in all internal waters, the seabed isunder provincial jurisdiction, whereas in offshore areas it is under federal care. Throughout the marine environment, the organisms in the water column are under federaljurisdiction. However, the management of certain resources, such as aquaculture and the commercial harvest of oysters and kelp, is under the purview of the provincial government.Keeping this in mind, in some circumstances dual designation of an MPA using both federal and provincial legislative authorities may be required. For instance, some provincialparks and ecological reserves may need the added protection provided by an MPA under the Oceans Act to achieve their management objectives.

The various federal and provincial statutes and their designations for protecting marine areas are outlined in Appendix B. These consist of:

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Marine Protected Areas under the Oceans Act

- Fisheries Closures under the Fisheries Act

Environment Canada

- National Wildlife Areas and Marine Wildlife Areas under the Canada Wildlife Act

- Migratory Bird Sanctuaries under the Migratory Birds Convention Act

Parks Canada

- National Parks under the National Parks Act

- National Marine Conservation Areas under the proposed Marine Conservation Areas Act

British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks

- Ecological Reserves under the Ecological Reserve Act

- Provincial Parks under the Park Act

- Wildlife Management Areas under the Wildlife Act

- Protected Areas under the Environment and Land Use Act

Sidebar #6 demonstrates how these designations relate and may be combined to achievespecific management objectives, and lists what criteria may be used to select the most appropriate designation(s) in each case.

Sidebar #6: Federal and Provincial Marine Protection Designations

MPA Protection Objectives Potential Protective Determining Criteria

Designation(s)

To contribute to the Oceans Act MPAs -representativeness

protection of marine Marine Conservation Areas -degree of naturalness

biodiversity, representative Marine Wildlife Areas -areas of high biodiversity

ecosystems and special Provincial Parks or

natural features. Ecological Reserves biological

Wildlife Management Areas productivity

(e.g. upwelling National Wildlife Areas -rare and endangered

environments, eelgrass beds, Migratory Bird Sanctuaries species

and soft coral communities.) -unique natural phenomena

-ecological viability

-vulnerability

-unique habitat

To contribute to the Oceans Act MPAs -areas of high biodiversity

protection and conservation Ecological Reserves and/or biological

of fishery resources and Marine Conservation Areas productivity

their habitats. Provincial Parks -rare and endangered

species

(e.g. spawning, rearing and -vulnerability

nursery areas.) -areas supporting unique or

rare marine habitats

-areas supporting

-significant spawning

concentrations or

densities

-areas important for the

viability of populations

and genetic stocks

-areas supporting critical

species, life stages and

environmental support

systems

To protect cultural heritage Marine Conservation Areas -presence of significant

resources of the Pacific Provincial Parks cultural heritage values,

coast of Canada and to such as physical artifacts

provide opportunities for and structural features

British Columbians and places of traditional use

others to explore, or of spiritual importance

understand and appreciate

the marine and coastal

cultural heritage of

Canada's Pacific coast.

(e.g. shipwrecks and areas

of cultural significance.)

To provide a variety of Marine Conservation Areas -degree of naturalness

marine and coastal outdoor Provincial Parks significance of cultural

recreation and tourism heritage values

opportunities. -presence of significant

recreation or tourism

(e.g. scenic areas, boat values

havens, marine trails, and -ability to attract and

dive sites.) sustain recreational use

-facilitate close contact

with the marine

environment;

-aesthetics

-rare, scarce, outstanding

or unique marine

recreation

features

To provide opportunities for Oceans Act MPAs -value as a natural

increased scientific Ecological Reserves benchmark;

research on marine Marine Wildlife Areas -value for developing a

ecosystems, organisms and Marine Conservation Areas better understanding of

special features, and Provincial Parks the function and

sharing of traditional National Wildlife Areas interaction of species,

knowledge. communities, and

ecosystems

(e.g. long term monitoring -value for determining the

of undisturbed populations.) impact and results of

marine management

activities

To provide opportunities for Oceans Act MPAs -ability to foster

education and to increase Ecological Reserves understanding and

awareness of marine and Provincial Parks appreciation;

coastal environments and our Marine Conservation Areas -area provides

relationship to them. Wildlife Management Areas opportunities for use,

National Wildlife Areas enjoyment, and learning

(e.g. interpretive signage, Marine Wildlife Areas about the local natural

nature tours, and outdoor Migratory Bird Sanctuaries environment

classrooms.) -accessibility

-suitability and carrying

capacity

6.0 Your Feedback on the Strategy

The public, marine stakeholders, First Nations, and coastal communities of British Columbia can participate in the implementation of the MPA Strategy by providing feedbackon this discussion paper. Please comment on any aspect of the document or, to assist you in providing your feedback, you may wish to address the questions below. All responses andinquiries should be directed by October 31, 1998 to:

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

450 – 555 West Hastings Street

Vancouver BC V6B 5G3

Telephone: (604) 666-1089

Fax: (604) 666-4211

B.C. Land Use Coordination Office

PO Box 9426 Stn. Prov. Govt.

Victoria BC V8W 9V1

Telephone: (250) 356-7723

Fax: (250) 953-3481

Thank you-we look forward to your replies.

Questions:

- Do you support the vision and objectives of the MPA Strategy? (Please see Section 4.0)

- Do you support the Minimum Protection Standards for MPAs? (Please see Section 2.0)

- Do you support the process for MPA identification, assessment and decision-making? (Please see Section 5.0)

- Do you support the formation of an inter-governmental coordinating body? (Please see Section 5.3)

- Should some form of public advisory committee be established? If so, how should it be structured and what role should it have?

- Do you support tailored MPA planning processes being conducted in unplanned areas? (Please see Section 5.4)

- Do you support the learn-by-doing approach and the identification of MPA pilot projects? (Please see Section 5.5)

- Should we define targets for the MPA Strategy, and, if so, what should these targets be? (Please see Section 5.6)

Appendix A: Principal Participating Agencies in the Development of the Marine Protected AreasStrategy

Department of Fisheries and Oceans

B.C. Land Use Coordination Office

Parks Canada

B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks

Environment Canada

B.C. Ministry of Fisheries

Appendix B: Federal and Provincial Statutory Powers for Protecting Marine Areas

Agency Legislative Tools Designations Mandate

Fisheries and Oceans Act Marine Protected To protect and conserve:

Oceans Canada Areas fisheries resources, including marine mammals and their habitats

(Federal) endangered or threatened species and their habitats

unique habitats

areas of high biodiversity or biological productivity

areas for scientific and research purposes

Fisheries Act Fisheries Closures Conservation mandate to manage and regulate fisheries, conserve

and protect fish, protect fish habitat and prevent pollution of

waters frequented by fish.

Environment Canada Wildlife Act National Wildlife To protect and conserve marine areas that are nationally or

Canada Areas internationally significant for all wildlife but focusing on

(Federal) Marine Wildlife migratory marine birds.

Areas

Migratory Birds Migratory Bird To protect coastal and marine habitats that are heavily used by

Convention Act Sanctuaries birds for breeding, feeding, migration and overwintering.

Parks Canada National Parks Act National Park To protect and conserve for all time marine conservation areas

(Federal) Proposed Marine National Marine of Canadian significance that are representative of the five

Conservation Areas Conservation Natural Marine Regions identified on the Pacific coast of

Act Areas Canada, and to encourage public understanding, appreciation and

enjoyment.

Ministry of Ecological Reserve Ecological To protect:

Environment, Act Reserves representative examples of BC's marine environment;

Lands and rare, endangered or sensitive species or habitats;

Parks unique, outstanding or special features; and

(Provincial) areas for scientific research and marine awareness.

Park Act Provincial Parks To protect:

representative examples of marine diversity, recreational and

cultural heritage; and

special natural, cultural heritage and recreational features.

To serve a variety of outdoor recreation functions including:

enhancing major tourism travel routes;

providing attractions for outdoor holiday destinations.

Wildlife Act Wildlife To conserve and manage areas of importance to fish and wildlife

Management Areas and to protect endangered or threatened species and their

habitats, whether resident or migratory, of regional, national

or global significance.

Environment and Land "Protected Areas" To protect:

Use Act representative examples of marine diversity, recreational and

cultural heritage; and

special natural, cultural heritage and recreational features

Link to this site for the Klallum language, and a story by Thomas Charles .

Link to this site for the Klallum language, and a story by Thomas Charles .