Ed Note : This document was scanned from the original using an OCR so that some of the scientific names may be incorrectly indicated also the images have not been included. The links provided are to the geographic locations which are linked to the Metchosin Coastal website

Race Rocks National Marine Park A Preliminary Proposal

Indian and Northern Affairs, Parks Canada

(Affaires Indiennes et du Nord;Parcs Canada)

NATIONAL PARKS DOCUMENTATION CENTRE

D. Hardie and C. Mondor .

Marine Themes Section

Parks System Planning Division

National Parks Branch

February 1976

Document No. 10 726R1

Contents

| Introduction |

i |

| 1. Regional Context |

1 |

| 2. Natural Systems and Dimensions of the Proposed Race Rocks National Marine Park |

7 |

| 3. Park Site Resource Analysis |

37 |

| 4. Park Concept |

47 |

| Appendix |

|

Introduction

At the First World Conference on National Parks held in Seattle in 1962, an important resolution was passed that participating countries should establish National Marine Parks.

In response to this resolution and being desirous of protecting outstanding areas and features of Canada’s marine environments as part of the national heritage, the Canadian Cabinet in January 1971 endorsed the National Marine Park concept. In that same year, a Federal Task Force was created to examine federal responsibility and jurisdiction relating to the establishment of a National Marine Park on Canada’s west coast.

Following the completion of this task a second Interdisciplinary Federal-Provincial Task Force Working Group was established in 1972. This Task Force, subsequently selected the marine and coastal area surrounding Race Rocks as one of several sites in the Strait of Georgia and Juan de Fuca Strait warranting further study as a potential National Marine Park.

In 1973, the Province of British Columbia responded favourably to the Race Racks proposal. As a result, a second Federal-Provincial Task Force was established consisting of members of the British Columbia Parks and Recreation Branch and the Parks System Planning Division of the National Parks Branch.

The Task Force was given the responsibility of developing a proposal for establishing the Race Rocks area as a National Marine Park.

As the industrial base in the Strait of Georgia – Puget Sound region continues to expand with increased population growth, the need to preserve parts or sections of the coastal and marine environs for recreation and ecosystem conservation has become an ever increasing requirement. It is within this context that the Race Rocks National Marine Park has been conceived and ultimately planned.

1. Regional Context

Geographical Setting

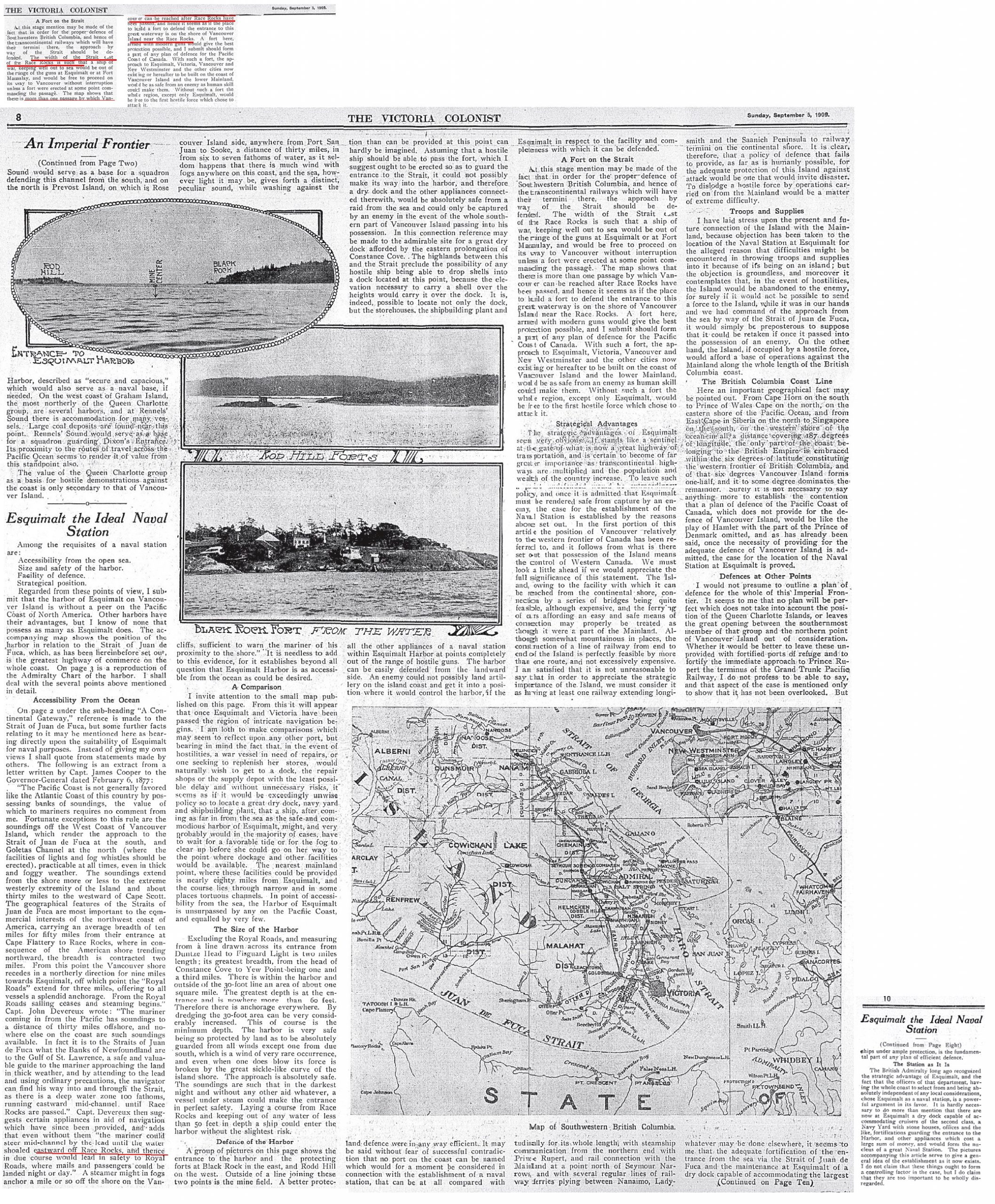

The proposed Park is located in the southwest portion of the Strait of Georgia – Puget Sound Lowland, an area which commands six percent of the combined area of British Columbia and Washington State and two thirds of their combined populations. Victoria and vicinity with a population of two hundred and fifty thousand is the largest urban centre in proximity to the proposed Park. All of the major urban centres on Vancouver Island as well as the cities of Vancouver, Tacoma and Seattle Washington are located within a radius of one hundred air miles. These centres have a combined population of over four million.

Proposed Park Boundaries

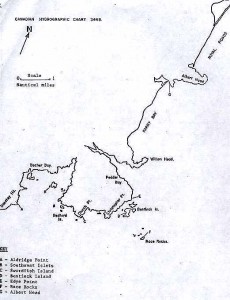

The proposed Park consists of approximately twenty square miles of surface water and offshore lands defined on the west by Sooke Peninsula in a straight line from Beechey Head to Rosedale Rock and on the east by a line extending from Rosedale Rock to Fisgard Light. The Park fronts on the regional land districts of Sooke, Metchosin and Esquimalt and encompasses some thirty-six miles of rugged shoreline, much of which remains in a relatively undisturbed state. The proposed shoreland component includes portions of Rocky Point, Albert Head Peninsula and Aldridge Point and totals some two and one half square miles (see map 1).

Regional System of Parks

In the Strait of Georgia – Puget Sound Lowland there are over two hundred recognized parks and recreation areas. Over sixty of these parks are located in coastal areas and provide facilities for water-based recreation activities. A system of Ecological Reserves, bird sanctuaries and Outstanding Natural Areas (U.S. designation) have been established to preserve outstanding natural ecosystems in the region.

Click to enlarge

The Park, lying west of Victoria commands easy access by road and water. Two major road networks provide access to existing shoreland areas, beach and marina facilities. A semi-integrated system of national, provincial and regional parks is found in the immediate backshore area adjacent to the proposed Park. Several single family sub-divisions and country estates are scattered throughout the shoreland while gravel pit and private recreation facilities are examples of commercial and industrial developments.

The visitor service facilities in the shoreland areas adjacent to the Park and surrounding region provide basic services such as: research centres, stores, motels, gas stations, dive shops, hospitals, museums, universities, and charter boat services.

Marine Setting

The Park is located in the transition zone between the Vancouver Island Inland Sea and the Pacific West Coast Marine Region. These two regions are part of a much larger oceanic system, namely the Pacific Coastal Domain, a temperate faunistic province extending from the middle of Baja California into the Bering Sea.

Tides and currents of varying velocities and direction control the exchange of waters as well as the chemical and physical properties of the water column in the Park and in Juan de Fuca Strait in general. The oceanographic phenomenon associated with this transition zone are responsible for the development of an outstanding marine environment with varied and abundant intertidal and subtidal community assemblages

A variety of erosional and depositional phenomenon characterize the coastal zone. The coastal geomorphology is controlled by the structural geology and the various facets of erosion and deposition common to the land-sea interface. The relatively undisturbed rugged volcanic coastline with secluded beaches, headlands, marshes, steep sandcliffs and offshore islands, offers a striking contrast to the more industrialized coastline surrounding Victoria to the east.

A rich coastal and natural marine history combined with a congenial climate makes the Race Rocks area an excellent setting for Canada’s first National Marine Park.

2. Natural Systems and Dimensions of the Proposed Race Rocks National Marine Park

2.1 Natural Resources

2.1.1 Climate

The climate of the Park is influenced by the surrounding coastal mountain systems and to some extent by the drift of the warm Japanese Kuroshio Current. Three climatic zones are recognized in the Park and are described below.

Cool Mediterranean Climate

Located in the rainshadow of Washington State’s Olympic Mountains and the Insular Mountains of southern Vancouver Island, the eastern portion of the Park is dominated by a characteristically cool Mediterranean climate. Summers are cool and dry, often to the point of drought; winters are wet and it is rarely very cold. The shoreland areas assume a parkland character and are dotted with groves of Arbutus and Garry Oak – tree species characteristic of regions without harsh climatic extremes. This climate, rare to the Canadian landscape gives way to a more transitional climate westward along the coast.

Transitional Climate

West of Race Rocks, summers are cooler while winters, being subject to the stormy influence of the more open Strait, are cooler and wetter than areas to the east. Fog is prevalent along the coast from Race Rocks to Beechey Head during the fall and winter. An annual average of fifteen annual fogs occur between August and October.

Maritime Climate The maritime climate common more so to the coastal regions north of the Park occasionally intrudes southward into the Becher Bay and Rocky Point regions. This system brings with it cool, wet and foggy weather primarily during the fall, winter and spring seasons.

Park Climate The coastal zone of the Park experiences less than 15 inches of snow per year and much of this melts soon after reaching -the ground. The southeasterly and southwesterly gales which blow frequently in the fall and winter months subject the Park to stormy weather. The combination of the rugged shoreline and strong wave action creates a magnificent setting to experience the ferocity of Pacific storms. The climatic phenomenon of the Park from one area to another and throughout the seasons is perhaps the most exciting yet restrictive aspect of the area,

It is not uncommon to experience on any one day a bright sunny day in the eastern portion of the Park and a dense, cool and damp flog in the western part, particularly west oil Race Rocks.

This chart illustrates the seasonal and spatial climatic variations for the Park area and Victoria.

| |

Precipitation Mean Annual (in inches) |

Temperature Mean Daily (Max. Summer) (¡F) |

Temperature (Mean Annual) (¡F) |

| Becher Bay |

39.57 |

67 |

49.2 |

| William Head |

35.67 |

67 |

48.7 |

| Esquimalt |

31.09 |

67 |

50.0 |

| Victoria |

25.87 |

66 |

50.1 |

Much of the coastal lowland region from William Head to Victoria can expect a mean of 2,200 hours of bright sunshine – the highest of all Canadian stations outside of the southern prairies.

The more unsettled weather of the western section of the Park will periodically limit activities somewhat especially during the fall and winter months.

Nevertheless, the long days with abundant sunshine and dry weather conditions offer unlimited possibilities for the pursuit of recreational, scientific and interpretive activities during the summer months.

2.1.2 Geology and Geomorphologic Processes of the Coastal Zone-– (Geology of Race Rocks)

In the coastal zone of the proposed Park are some of the most interesting geological and geomorphological features to be found on southern Vancouver Island. These include features of both original parent material and landforms that have been formed since the last ice age.

Two basic geologic formations, namely the Vancouver Formation of the Lower Mesozoic and the Metchosin Formation of the Upper Eocene dominate the land-sea interface. Glacial drift deposits of considerable depth dominate the shoreland in the eastern portion of the Park. Other glacial features such as: glacial grooves, abrasion and striation marks, record two epochs of glacial occupation and two corresponding epochs of glacial retreat.

The proposed Park and adjacent shoreland can be divide into three broad geologic and geomorphologic units as follows:

1. INNER COAST – ROYAL ROADS BAY AND PARRY BAY

The intertidal and subtidal environs in this coastal unit are characterized by gradually sloping sand, silt and mud flats to an average depth of 30 fathoms. In the intertidal area, sand and gravel beaches and mud flats are exposed at low tides.

The immediate subtidal area is covered with a diverse mixture of sands, silts and muds. Areas of exposed and partially exposed bedrock are interspersed throughout the shoreland, the intertidal and subtidal areas.

Glacial drift deposits its formed along the shore from Parry Bay to Royal Roads have been retrograded to form steep seacliffs up to one hundred feet in height. Much of the eroded sands and gravels from the cliffs have been carried eastward by longshore currents to form spits, baymouth bars, beaches, tidal flats and other coastal geomorphologic features at Witty’s Lagoon, Albert Head and Esquimalt Lagoon.

At Albert Head, basalts of the Metchosin formation occur as pillow lavas. It is believed these deposits were either erupted beneath the ocean floor or flowed from the sides of ancient volcanic islands into the sea.

At Albert Head and William Head, boulder beaches, gravel beaches, subtidal bedrock with smooth vertical faces, and bottom sediments of sands, muds and clays are characteristic.

A Generalized Profile of Royal Roads Bay and Parry Bay – Inner Coast.

(Not to scale)

2. EAST ROCKY POINT – RACE ROCK SHOALS

Interspersed with islands, this area is the most variable geomorphologic unit in the Park. The area incorporates diverse shore features, such as: talus slopes, abrasion platforms, shingle beaches, vertical rock faces, sandy coves, boulder beaches and cobble stone coves.

The subtidal area is a series of jagged ledges and channels with undersea talus slopes, current scoured bedrock, reefs, shoals, exposed islets and rocks, undersea ridges and cliffs. In the quieter areas in the lee of, some islands tombolos, spits, caves, and stacks are common. In the subtidal areas, sands, muds, and silts are characteristic to a depth of 45 fathoms.

A Generalized Profile Sketch of West Rocky Point Beecher Bay Basin (Not to scale)

3. WEST ROCKY POINT – BECHER BAY

The coastal zone of the west Rocky Point – Becher Bay is characterized by rather broad shallow bays between equally broad and irregular headlands with offshore islands and rock outcrops. This shoreline is cut largely in Metchosin Volcanics and Sooke Intrusive rocks and presents all the irregularities of a depressed, glaciated rock surface with added features such as: undersea caves, stacks, islets, coves and wave chasms all which were produced by the more successful attack of the waves on sheer zones, joints and dykes.

In Becher Say, steep basaltic shoreline cliffs and isolated pocket beaches give way to a subtidal environment characterized by shoals, exposed undersea basaltic ledges, ridges, reefs, shallows and islets.

A progressively steepening bottom to over seventy fathoms (420 feet) occurs to the outer portions of the Bay. The deeper portions of the basin are covered with vast deposits of sands, silts and muds.

The shoreland and subtidal geology and geomorphology contain great potential as an interpretive feature of the Park. The purely scenic experience of the Park visitor will take on an added dimension if he becomes aware of the geological phenomena which have altered and shaped the coastal zone of the Park.

a) Sandcliffs of superficial glacial deposits at Witty’s Lagoon

b) Pillow lavas at Albert Head

c) Sooke formation at Aldridge Point

Generalized Profile Sketch of East Rocky Point – Race Rocks Shoals. (Not to scale)

2.1.3 Oceanography

The important oceanographic features which will have a bearing on the conservation and use aspects of the Park are tides, currents, wave action, water temperature and underwater visibility.

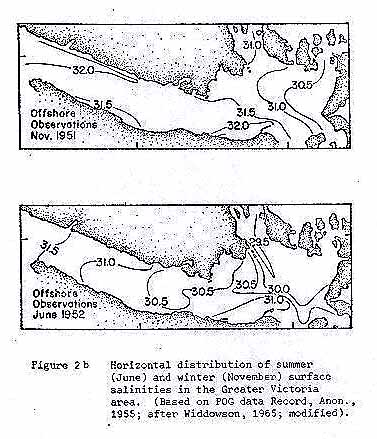

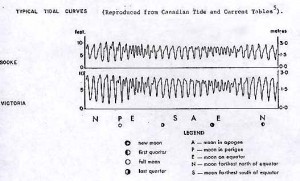

The surface waters in the Park consist of a mixture of warm brackish Georgia Strait water and cold, saline ocean water which is relatively rich in nutrients. The tides, a dominant factor controlling the type and distribution of intertidal life forms, are of the mixed, mainly diurnal type. The lower low tides occur in the daylight hours during spring and summer (March to August) and during the evening in the fall and winter. The mean tidal range in the eastern portion of the Park is 5.7 feet. In Becher Bay tides approximate 6.1 feet while during large tides the range may reach 9.9 feet.

Tidal action in combination with shoreline configuration creates weak to strong currents along the shoreline proper and between offshore islands and islets. These currents achieve speeds of 2 to 7 knots and change direction according to tide, wave and wind direction. The strong currents west of William Head to Beechey Head represent a hazard to the. diving community.

The indented character of the shoreline, offshore islands, shoals, the fetch distance across Juan de Fuca Strait and the direction of storm winds affect the character and size of waves. Wave action is more pronounced in the western portion of the Park due to the exposure to the outer portion of Juan de Fuca Strait. In the eastern portion of the Park, southeasterly gales produce smaller swells (8 feet to 12 feet) due to the limited fetch across the Strait.

Rip tide at Race Rocks

The variability in undersea topography results in waves being reflected, diffracted, and refracted in irregular patterns. This factor combined with abrupt wind and current changes can result in hazardous inshore water conditions.

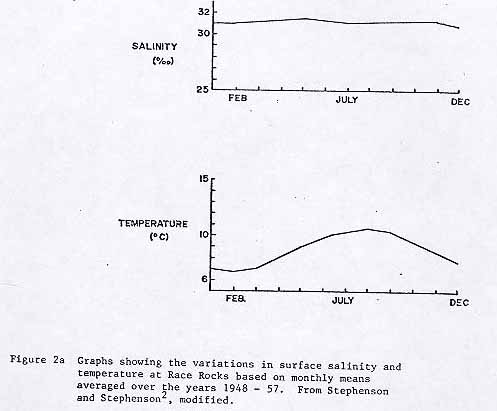

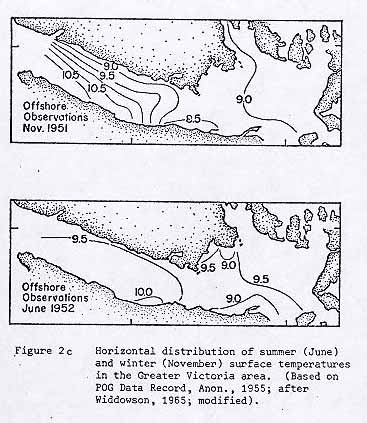

Water temperature in the Park is everywhere greater than 7¡C with no distinct thermocline occurring. Mean surface temperatures are 7¡C to 8¡C in January, rising to 10¡C to 11¡C in August and September. In summer, the water is slightly cooler during flood than during the ebb tidal phase. Tidal flushing and turbulent currents reduce vertical layering of water masses. Surface salinity values in the Park average 31 0/00 throughout the year and are characteristic of the waters in Juan de Fuca Strait. Water clarity in the Park is a seasonally dependent phenomena, being largely determined by the phytoplankton content of the water. In winter, low phytoplankton populations result in good underwater visibility (sometimes greater than 50 feet) except after storms. In summer the situation reverses. There is no significant turbidity due to freshwater run-off in the Park area.

Diver exploring the underwater communities at Race Rocks

Fair weather diving and water activities occur during July through September when water temperatures are high. The lack of winter ice in the Strait allows for year round diving and boating in certain areas of the Park. Strong currents restrict diving in some areas to specific times of day throughout the various seasons of the year.

2.1.4 Marine life of the Intertidal and Subtidal Zone

The Pacific Coast

The rich variety and abundance of seashore life of the Pacific coast is due in large measure to the nutrient rich waters, relatively uniform seasonal range of temperature and freedom from winter icing. Approximately three times as many of the fauna of most major crustacean groups are found here as at equivalent latitudes on the Atlantic coast.

Echinoderm fauna is perhaps the richest in the world while sea moss fauna is abundant and diverse although not yet completely documented.

As on the Atlantic coast, the invertebrate fauna of the Pacific coast contains two main elements: a sub-arctic group and a larger Pacific boreal assemblage. A small number of warm-water species, native to places south of Point Conception, California, or elsewhere in the world, are isolated in the summer-warm surface waters of the Strait of Georgia. Practically all phyla of invertebrate animals known to frequent the Pacific sea-shore are found in and around the Park.

I

Southern Vancouver Island – Juan de Fuca Strait

In the area of Canada’s Pacific coast, the northern portion of the transitional zone between the California and Aleutian Faunal Regions overlap resulting in an immensely diverse marine fauna.

Park Marine Life

Marine flora and fauna species of the partially exposed southwest coast of Vancouver Island gradually merge here with the species of the exposed (heavy wave action) west coast of the island. Species entering Juan de Fuca Strait from the more open Pacific extend their range to the semi-exposed coast in the western portion of the Park but gradually disappear as they enter the more sheltered environs eastward to Victoria.

This transition in association with high current velocities and rich food supply results in a concentration of echinoderms, crustaceans, mollusks, coelenterates and plants in higher population densities than occurs elsewhere in the region. Some species, usually rare, in terms of distribution and abundance may be found in the proposed Park area in surprising numbers.

Representative Species

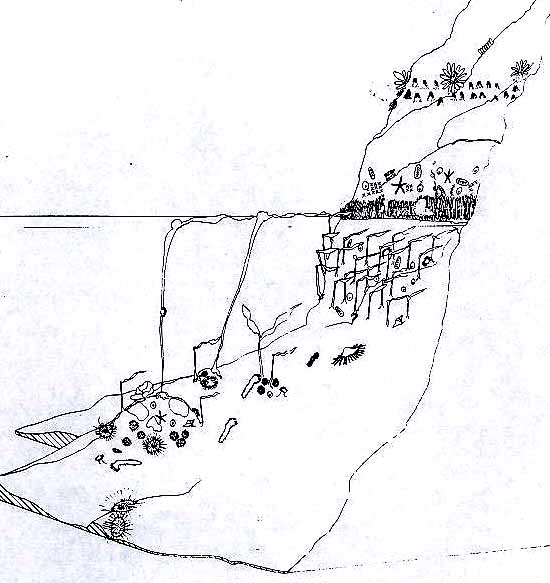

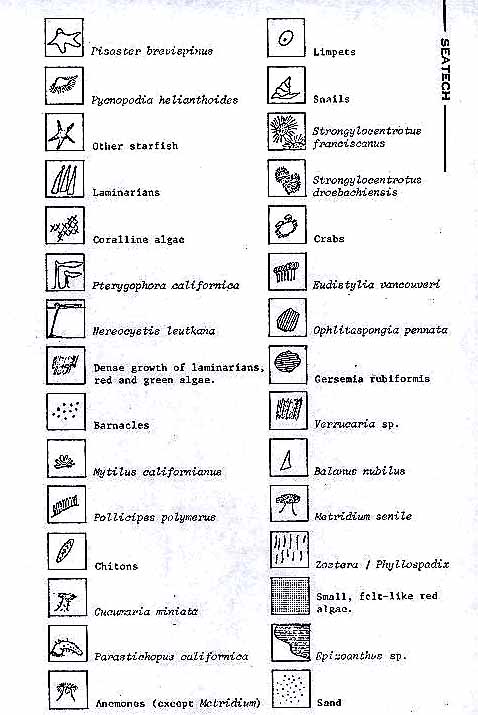

Intertidal Communities:

The intertidal species of macroflora and macrofauna are characteristic of the southwest coast of Vancouver Island. The intertidal flora and fauna are diverse and abundant in most situations becoming somewhat less diverse, but no less abundant in areas subject to continuous heavy wave action. The intertidal areas in the Park are very usual of northern cold-temperate regions – a strong representation of barnacles, mussels, Fucus and laminarians, arranged in a typical manner.

The barnacles Balanus glandula, B. carious, the mussel Mytilus Californianus, the snails Littorina sps. and the limpets Acmaea sps. are frequent in the upper intertidal zones at Albert Head, Rocky Point and Becher Bay. An unusual number of the gregarious anemone Anthopleura elegantissima, the large white anemone Metridium senile and the colourful anemone Epiactus prolifera dominate the lower intertidal and upper infralittoral rocks in the more exposed areas of the Park – especially where “cryptic habitats” are dominant.

Here also, is a marked abundance of a variety of echinoderm fauna, several of which are of a truly remarkable size. Conspicuous species of the infralittoral fringe and zone are the very large sunflower star Pycnopodia helianthoides, the common starfish Pisaster orchraceus., and Pisaster brevispinus.

Splendid echinoids include the green sea urchin, the large purple urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus and the reddish cucumber Cucumaria miniata.

Fucus and laminarians are abundant, some gradually disappearing in the more protected eastern portions of the Park. Among the seaweeds, Nereocystis exceeds thirty feet in length; Egregia, Cystoseira, and Alaria exceed ten feet; and there are smaller algae, the colonies which attain sizes up to six feet, including species Ulva, Iridaea heterocarpa, Egregia menziesii, and Zostera marina to name but a few.

In the eastern portion of the Park, salt marsh, lagoon and tide flats are conspicuous habitats. The marine macroflora and macrofauna assemblages are very different, with the macrofauna being less conspicuous to the observer than those associated with the rocky shores described above. Here, the clams Clinocardium nuttallii, Saxidomus gigantus and Protothaca staminea, and Acmaea digitatis are numerous on the tidal flats and among the rocks in the intertidal areas around Albert Head and Witty’s Lagoon.

The green sponge Halichondria, the red encrusting sponge Ophlitaspongia pennata and the coralline algae Lithophyllum sp. and Bossiella sp., are frequent in the infralittoral zone. The six-rayed starfish Leptasterias hexactis. the shore crab Hemigrapsus nudus, the kelp crab Pugettia producta and Cancer magister inhabit the intertidal rocks. Recognizable among marine worms are the sabellid worm, Eudistylia vancouveri the colonial Eudistylia polymorpha and the free swimming Nereis vexillosa.

Subtidal Communities:

The subtidal macroflora and macrofauna are constant and uniform in areas subject to moderate to weak currents. In areas of high-velocity currents (primarily Race Rocks)-a unique biotic community is found. The unusual feature is not only the appearance of species not found elsewhere (Gersemia sp., Gorgonocephalus sp.) but also the unusual abundance of some ubiquitous species Corallina sp. and Epiactis prolifera. Here also, Balanus cariosus achieves a prickly texture and Balanus nubilis excessive sizes (up to 4 inches). The rare occurrence of disjunct echinoderm species such as the seastar, Ceremaster articus, numerous specimens of the solitary coral Balanophyllia elegans, the abalone Haliotis kamtschatkana., the crab Crytolithoides sp., and at least one species of anemone as yet unidentified attests to the unusual character of the subtidal communities of the rocky shore environs particularly in the transition zone of the Park.

Critical Habitats:

The degree to which important life stages or entire life histories of species are dependent on an area is an important aspect to consider in the designation of any National Marine Park*. The marsh, lagoon and offshore marine habitats in the Park function as underwater nurseries and feeding areas for the larval and mature stages of many fishes, echinoderms, coelenterates, crustaceans, mollusks, and other creatures. Conservation and protection of key habitats such as: lagoons, marshes, and high current velocity habitats in the Park and in the surrounding region will be a critical factor in maintaining healthy marine community assemblages.

Schematic Profile of Subtidal Macroflora and Macrofauna at Race Rocks

Naturalness:

The naturalness of a habitat relates to the degree of perturbation by man. Ray has noted that care should be taken that naturalness not exclude man’s use**. Although the Park lies close to Victoria, lack of public access to much of the shoreline areas has resulted in the development of a perfectly characteristic marine environment.

This abbreviated description of the invertebrate marine life scarcely does justice to the immensely abundant, diverse and dynamic community assemblages found throughout the Park. Some species are common and beautiful while others are rare and fragile.

The protection and conservation of this spectacular array of marine life existing in a relatively unmolested and pollution free environment will be a paramount objective of the overall planning and development of the Park.

* Ray. G.C. Critical Marine Habitats., May 1975.

** Ibid.

a) Hermissenda crassicornis at Race Rocks

b) Ceremaster arcticus at Race Rocks

c) Cancer Magister at Witty’s Lagoon

d) Weed-covered rocks surrounding tide pool at Fraser Island

e) Mopalia muscosa at west Bedford Island

f ) Pisaster ochraceus at Aldridge Point

g) Epiactus prolifera at Race Rocks

h) Metridium senile at Swordfish Island

i)Hydro coral Allopora pacifica at Race Rocks

j) Aglaophenia sp. and Abietinaria sp.at Great Race Rock

k) Triopha carpenteri at Bentinck Island

l) Strongylocentrotus franciscanus, Epiactus prolifera, Balanophyllia elegans and Allopora pacifica at Race Rocks

2.1.5 Marine Fishes

The living habits and adaptations of many fishes in the proposed Park are remarkable. There are only a few species of Pacific coast fishes of the temperate latitudes that cannot be found in the Park. There are at this time no known rare or endangered species occurring in the Park. In addition, the currents passing in and out of the Park provide passive transport for migrating species. The mixed waters of Juan de Fuca Strait support abundant plankton growth which in turn supports a wide variety of pelagic fishes.

Representative Species:

Principle species common to Juan de Fuca Strait can be found in the Park. Fishes most likely to be seen by the park visitor who visits the sea beach or spends some time on coastal Park waters include: the dogfish Squalus acanthias, the lingcod Ophiodon elongatus, the black rockfish Sebastes melanops and greenling Hexagrammos lagocephalus.

In the intertidal areas numerous species of Sculpin, particularly the tide pool sculpin Oligogattus maculosus, and snailfish Liparis florae, are common in the rocky shore tide pools. Several species of Gobies can be found in great numbers in the muddy tide pools.

Migrants:

The Park is known to be frequented by many migrant fish species during annual migrations through the Juan de Fuca Strait. The coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch, and chinook salmon, 0. tshawytscha are two major migrants. These are accompanied by other salmonids and schooling fishes such as the anchovy, herring, sole, and variety of other ground fish.

Critical Habitats:

The extensive eelgrass and kelp beds of the coastal marshes, lagoons, bays and passages, function to some degree as nursery and rearing areas for the larval and maturing stages of many marine fishes found in the Park and surrounding regions.

a) Greenling Hexagrammos lagocephalus at Pedder Bay

b) Rockfish Sebastodes caurinus at Whirl Bay

C) Grunt sculpin Rhamphocottus Richardsoni with the sea cucumber Parastichopus californicus in background at Albert Head

Shellfish:

Crabs and shellfish, particularly the Dungeness crab Cancer magister, and butterclam Saxidomus giganteus and other bivalve mollusks, are common in the shallow bays and tide flats in the eastern portion of the Park. Scuba diving for abalone and rock scallops and digging for clams is common. Populations of these species are relatively still abundant in many areas of the Park.

Fishing:

No commercial fishing for salmon occurs in the Park. However, herring is fished on a commercial bases during designated seasons from Albert Head to Race Rocks just inside the Park boundary. Sports fishing for salmon is a major activity in the Park.

2.1.6 Shoreland and Marine Bird Life

The shoreland and marine areas of the Park abound with bird life. The birds frequenting the Park can be classified as abundant year round residents, common or uncommon migrants, winter visitors or accidentals. Bird populations are most conspicuous during the spring and fall months. The variety of habitats, availability of food and the relatively undisturbed nature of the shoreland and marine environment are partially responsible for attracting the large numbers of sea’brds, song-birds, shorebirds and waterfowl to the Park. ”

Representative Groups

Seabirds and Waterfowl:

The Park is frequented by a variety of seabirds from the Diving, Dabbling Duck, Totipalmates, Tubenosed Swimmer, and Alcids families. Year round residents include the pelagic cormorant Phalacrocorax pelagicus, the pigeon guillemot Cephus columbia, the common murre Uria aalge, the glaucous-winged gull Larus glaucescens and the black oystercatcher Haematophus bachman. Common migrants of the Pacific flyway frequenting the Park are the Brandt cormorant Phalacrocorax penicillatus, the black brant Brant nigricans, Bonaparte’s gull Larus philadephia and the mute swan Cygnus olor.

Some common winter visitors include: the bufflehead Bucephaca albeola, the white-winged scoter Melanitta degandi, the oldsquaw duck Clangula hyemalis, and the ancient murrelet Synthliborampthus antiquus.

Rare Occurrences Uncommon visitors such as the rhinoceros auklet Cerorhinca monocerata., Cassin’s auklet Ptychoramphus aleuticus. the ring-billed gull Larus delawarensis and the black-footed albatross, Diomedea nigripes are sighted on occasion. Rare occurrences such as that of the white-fronted goose Anser albifrons. the whistling swan Olor columbianus and the Pacific kittiwake, add to the orthinological significance of the Park. Many of these birds frequent the Park in response to the availability of food and protection from exceptionally bad weather.

Shorebirds:

The occurrence of marshes, lagoons, tide flats and offshore island habitats, attract and support a wide variety of shorebirds and waterfowl.

Concentrations of shorebirds representing over ten species occur in attractive feeding areas where mudflats are exposed at low tide. Common visitors include the spotted sandpiper Actitis macularia, the rock sandpiper Erolia ptilocnemis, the black-bellied plover Squatarola squatarola and the greater yellow legs Totanus melanoleucus.

Song-Birds and Birds of Prey:

Shoreland areas support a variety of song-birds, birds of prey and chicken like birds such as the blue grouse Denoragapus obscurus and the mountain quail Oreortyx pictus. Rarer song-birds include the Oregon junco Junco oreganus, MacGillivary’s warbler Oporornis tolmiei. The osprey Pandion haliaetus and the bald eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus are the most conspicuous birds of prey.

a) Pelagic cormorants nesting at Race Rocks

b) Bald eagle at Christopher Point

c) Mute swan on Blue Lagoon

d) oystercatcher at Rocky Point

Critical Habitats:

As is true for nearly all natural situations close to a technological society, the Park is threatened with the possibility of man-made environmental perturbations which may alter the structure, stability, or the very existence of one or more of the biological communities present. The increased pressure being exerted on key feeding, resting and roosting areas in the Park and region by recreation and other marine activities poses a threat to the bird communities of the Park.

Preservation of vital shoreland and marine habitats (for example, Witty’s and Esquimalt Lagoons, Race Rocks and Bentinck Island and offshore Islands in Becher Bay) will assure, to a certain degree, continued abundance and diversity of Pacific coast birdlife in the Park and surrounding regions.

2.1.7 Mammals

Marine mammals have always been a strong attraction for visitors to the seacoasts of Canada. As a consequence, areas known to be frequently or seasonally used by these animals become particularly important in providing for typical or unique samples of marine mammal habitat.

Many of the marine mammals, although seasonal in their visitation, are perhaps the Most spectacular and readily visible components in the Park – each possessing a distinctive adaptability to the marine environment.

Due to the isolation of Vancouver Island from mainland British Columbia many of the more common shoreland animals have developed as distinctive subspecies.

Marine Mammals:

A number of cetaceans and pinnipeds known to occur in British Columbia waters frequent the Park. The most common of these are the harbour seal Phoca vitulina, the northern sea lion Eumetupias jubatus, the California sea lion Zalophus californianus, and the harbour porpoise Phocaena vomerina.

Rare Occurrences:

Less frequent visitors to the park include: the killer whale Orcimus orca., the northern fur-seal Callorhinus ursinus cynocephalus, the blue whale Balenoptera musulus, the minke whale Balaenoptera acutorostrata, the dall porpoise Phocoenoides dalli, and the Pacific striped dolphin Aagenorhynchus obliquides. Occasionally, the northern elephant seal Mirounga angustirostris is sighted at Race Rocks.

Shoreland Animals:

Many mammals common to the Coastal Forest and Gulf Islands Biotic Regions can be found in the shoreland areas bordering the Park. Here many species of shoreland mammals occur as distinctive subspecies in shoreland and upland areas adjacent to the Park. The Columbian blacktail deer Odocoileus hemionus, columbianus., the longtailed vole Microtus longicaudus, and several insular subspecies, the shrews Sorox cinereus striatori, and Sorex vagrans setosus, and the martin Martes americana caurina are noteworthy. The White-footed mouse Peromyscus maniculatus angustus, and Townsend vole Microtus townsend tetramerus are more numerous here than elsewhere on the island.

The river otter Lutra canadensis, the mink Mustela vison energumenos, the short-tailed weasel Mustela erainea anquinae and the racoon Procyon lotor vancouverensis are frequently seen along the shoreland areas. Larger preditors such as the cougar Felis concolor vancouverensis and the American black bear Ursus americanus vancouveri, are known to sometimes frequent the shoreland areas of Rocky Point and Becher Bay.

Critical Habitats and Species Protection The establishment of a Park in the region affords the opportunity to preserve vital habitats critical to the continuation of many shoreland subspecies of animals uncommon to other parts of Vancouver Island and mainland British Columbia. Also, it presents the opportunity to preserve critical feeding, resting, and pupping areas for many coastal pinnipeds and cetaceans, particularly the killer whale, which is still frequently captured in the Pedder Bay area on its migrations through the proposed Park area.

2.1.8 Shoreland Biota

The many years of logging and agricultural occupation of the land as well as the varied soils, irregular te~rain and transitional climate have had a marked effect on the type and distribution of vegetation from the coastal lowlands to the forested uplands adjacent to the Park.

Representative Flora:

Two major forest regions, namely the Coastal Forest and Gulf Islands find representation in adjacent shoreland areas. Three distinct forest communities have been identified in the shoreland areas adjacent to the Park. These are the Douglas-fir dry forest, the Douglas-fir wet forest, and the Western hemlock dry forest.

Dry Douglas-Fir

The dry Douglas-fir forest, covers the shoreland from Esquimalt Lagoon to Becher Bay. The forest cover ranges in character from dry, open woodlands to closed-canopy forests of western red cedar and grand fir.

The Garry oak, Quercus garryana., and arbutus, Arbutus menziesii, Canada’s only broad leafed evergreen, occur in association in this forest and create a parkland landscape typical of many mediterranean areas. A prominent feature in the parkland areas is the abundance of spring flowering bulbous and herbaceous plants.

Wet Douglas-Fir

The wet Douglas-fir forest is found primarily in the western extremities of the shoreland bordering the Park. There are no species endemic to the forest. Douglasfir is characteristically dominant, while western hemlock occurs as a secondary climax species. Arbutus and Garry’oak occur in small isolated pockets along the shoreline.

Dry Western Hemlock

The dry western hemlock forest occurs only in a small portion of the shoreland bordering the Park at Aldridge Point. The climax vegetation of this forest varies but western hemlock is the major climax dominant. Shrub species indicative of the zone include: the ninebark, Physocarpus capitatue, California rhododendron, Rhododendron macrophyllum, and red-flowering currant, Ribes sanguineum.

Rare Occurrences – Arbutus and Garry Oak

Few areas in British Columbia outside of the Gulf Islands have as good a representation of arbutus Garry oak parkland as the shoreland adjacent to the Park. On Rocky Point extensive stands of undisturbed Garry oak dominate the landscape while small groves of arbutus extend throughout the region in areas below 1000 feet.

The associated plant communities on this southern coast are in their own right a rare and unique heritage of the moderating influences of the ocean and surrounding

topography. Preservation of this special forest area will afford Canadians the opportunity to see and experience a truly unique shoreland landscape.

Arbutus at Aldridge Point

Garry Oak at Royal Roads Bay

2.1.4 Coastal and Marine Biology

2.2 Cultural Resources

2.2.1 Coastal and Maritime History

Prehistorically, the southern portion of Vancouver Island was the territory of the Coastal Salish Indians. The coastal lowlands from Victoria to Sooke were inhabited by the Songhees, Esquimalt and Sooke tribes.

Evidence of Indian habitation along the shoreland areas adjacent to the Park is best exemplified at Becher Bay, Rocky Point and Parry Bay. Petrologist of seals and whales may be seen on the black volcanic rocks in the vicinity of Aldridge Point. Rings and cairns of stones identify a major Indian burial site at Eye Point. Further east at Parry Bay ancient fortifications mark the site of an Indian settlement. This site has been identified as warranting consideration a future Natural Historic Site/Park. Scattered remnants of fishing camps, dumping areas and hunt camps are found throughout the shoreland areas adjacent to the Park. It was from this rugged coast that the various Indian tribes hunted and reaped the rich harvest from the sea.

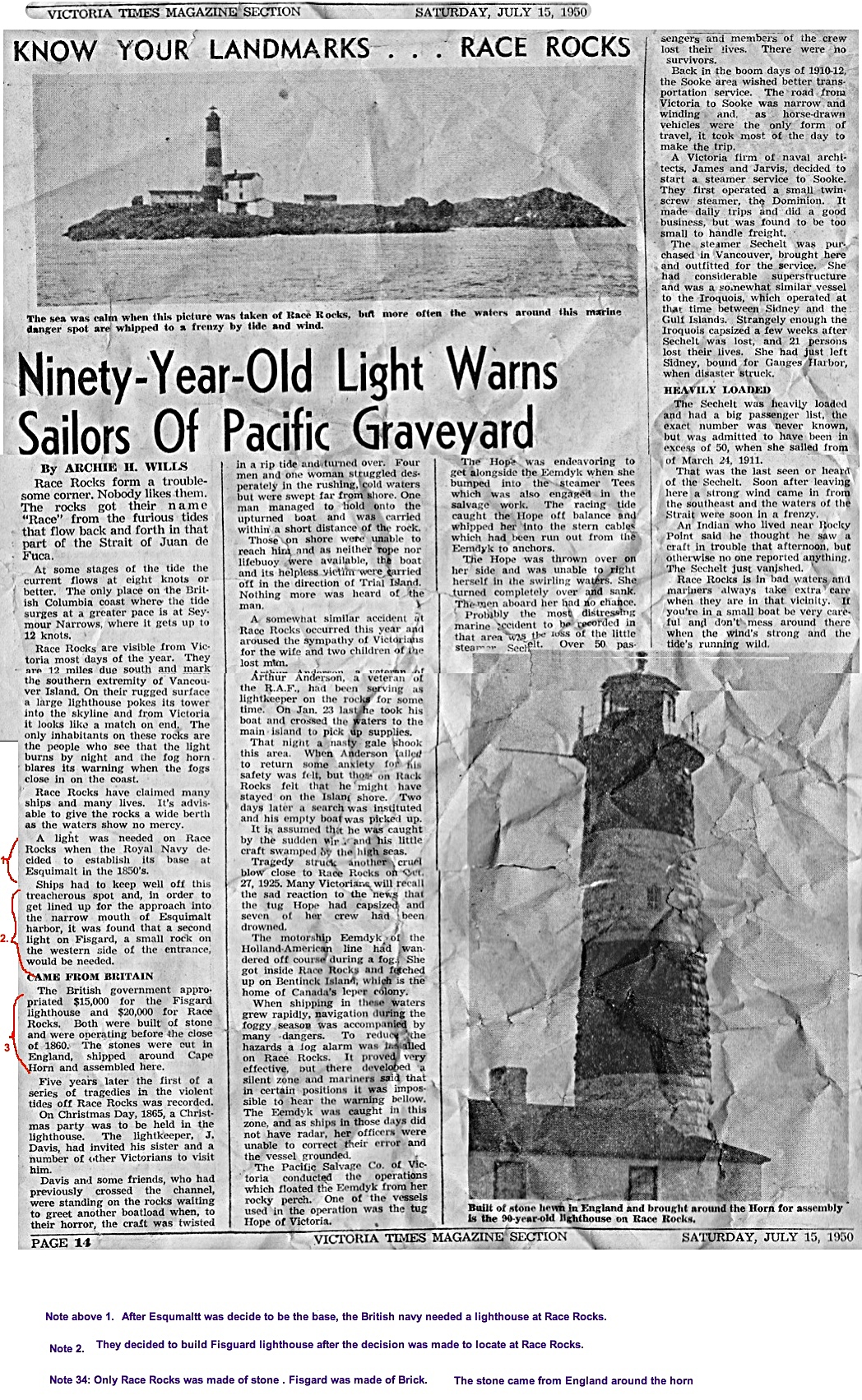

Exploration of the region dates back to 1592 when the Mexican explorer Juan de Fuca first visited Vancouver Island. Two centuries passed before Juan Perez, Cook, Valdes, Vancouver and others began the era of serious exploration. Mapping, exploration and settlement commenced in earnest during the fur trading period. By 1898 the port of Victoria had grown into the major trading centre of the region.

During the late 1800’s, railroads pushed north and west with the clearing and development of the land. The rail networks continued to expand as new logging and mining areas were opened in the interior of Vancouver Island.

The rapid growth of the fur trade also saw an expansion of shipping activity. A dynamic and complex shipping industry developed between ports of the Pacific northwest and Victoria. By 1900 scores of ships had gone aground or sank on the many shoals and small islands in the Park and surrounding regions.

Maritime History

The age of trans-pacific travel initiated the development of Canada’s first west coast quarantine station on William Head Peninsula. For 40 years plague ridden ships docked and transferred ashore men dying of plague, smallpox and other communicable diseases.

Race Rocks and Fisgard Lights, with their giant limestone blocks, were constructed in 1860 (ed note:corrected from 1860 and 1861). Today, they remain as one of the finest monuments to the history of aids to navigation and to the era of sail and steam on Canada’s Pacific coast. The wrecks of the Swordfish and S.S. Barnard Castle remain as vivid legacies of the many vessels that floundered in storms or were dashed against the jagged shoreline of the Park.

Fishard light at entrance to Esquimalt Harbour

Wreck of the Faultless at Wolf Island

Bentick Island was the first established leper colony on the Pacific coast and it continued to function in this capacity up until the early 1950’s. The population of lepers never exceeded twenty-two. Today thirteen graves stand as a memorial to those who lived and died on the island of the “Living Dead”.

a) Coastal Indian burial site at Edye Point

b) Coastal Indian petroglyph at Aldridge Point

Coastal Military History

With the advent of the Great War a series of coastal defences were constructed to protect the Royal Navy base at Esquimalt Harbour and the entrance to the Strait of Georgia. With the advent of World War II gun batteries were strengthened along the shoreland west of Victoria.

9.2 inch guns were constructed at Christopher Point, Mary Hill, and Albert Head. All posts were fully manned during the war but none fired a single shot in anger. Today, the old rusted gun implacements and flooded labyrinth of tunnels on Albert Head and at Mary Hill stand as silent reminders of the coastal military history of the Park and region.

Coastal History – Review

Shipwrecks, historic lights and gun batteries, Indian burial sites, and an abandoned leper colony, blend with the maritime landscape in making the Park a historical marine resource of truly national significance.

Abandoned gun batteries at Mary Hill

3. Park Site Resource Analysis

3.1 Preliminary Park Site Evaluation

3.1.1 Marine Resource Units

The purpose of the analysis section is to make qualitative statements about the various natural and natural phenomenon that were identified in the resource section and the relationships between them.

Climate, geology, vegetation and soils are the physical parameters employed to assist in the preliminary structuring of shoreland units. The watermass characteristics in combination with benthic community assemblages and marine mammal and bird distribution form the framework for the preliminary selection of the marine resource units.

The particular character of each of these units forms the basis for the development of a park “plan” as well as management guidelines governing preservation and use of the marine and shoreland resources. Areas with significant natural and cultural values (for example, ecologically sensitive areas) were also identified in each of the marine and shoreland units. The significant attributes of these areas are briefly described under each resource unit heading.

The following three marine resource units were identified as follows:of unique values)

1. Protected Inner Coast

2. Transition Coast

3. Semi-Exposed Outer Coast.

Protected Inner Coast

This resource unit is under the influence of a climatic pattern which approximates a winter wet, summer dry, never cold condition. The shoreland is sheltered and experiences pronounced wave action only during southeasterly gales in fall and winter. The following natural phenomenon are characteristic of this resource unit:

Parry Bay and Royal Roads Bay are subject to weak currents; tide range approximates 5.7 feet with low tides occurring during the day in spring and summer (March to August) and during the evening in fall and winter; 10 degC surface water temperature; variable water clarity; mean salinity approximates 31pt/oo yearly; steep glaciated nearshore topography; sediment transport by longshore currents; salt marshes and lagoons; significant geomorphologic features and variable coastline.

Areas with Significant Natural and Cultural Values

Esquimalt and Blue Lagoons

*Saline lagoon ecosystems

*Sand, mud, silt subtidal habitats

*Sandspit and dune ecosystems

*Nursery and rearing area

*Waterfowl and shorebird feeding and breeding area

*Tide flats (high concentration of univalves)

*Sand-gravel beaches

*Shellfish habitat

*High nutrient and detritus production

Albert Head

*Rocky headland (Gulf coast forest representation)

*Basaltic cliffs Metchosin volcanics)

*Undersea and shoreline pillow lavas

*Arbutus – Garry oak stands

*Military structures – marine military history

*Seabird islets

*Kelp forests

*Rocky intertidal and subtidal habitats

*Rocky shore tide pools

*Marine mammals

Witty’s Lagoon

*’Salt water marsh (good example of natural succession) vegetation communities

*Fresh water estuary

*Waterfalls

*Lagoon

*Arbutus – Garry oak stands

*Tide flats

*Surge channel

*Sandspit and beach (sand)

*Aspen parkland

*Sandy beach and subtidal marine life

*Natural nursery area

*Waterfowl and shorebird feeding and roosting area

*Marine mammals (harbour seals)

a Albert Head Peninsula

b Blue Lagoon

c Witty’s Lagoon

d William Head Peninsula

William Head

*Rock headland (scenic view)

‘Arbutus – Garry oak stands

*Deepwater habitats

*Rocky shore habitats

*Pocket beaches

*Protected bays *

*Kelp forest (seasonal)

*Rocky tide pools

‘Rich subtidal marine life

‘Marine mammals (harbour seals and killer whales)

*Contemporary maritime history

Transition Coast

This marine resource unit has a variable climate.pattern with frequent fogs and unsettled weather.The shoreline is exposed and experience’s pronounced wave action and tide surge.

The following natural phenomena are characteristic of this resource unit:

Offshore areas are subject to strong current and tide action; tide range approximates 6.1 feet ‘

but may reach 9.9 feet; tide occurrence similar to inner coast; 7¡C to 9¡C surface water temperature; water subject to constant mixing; whirlpools common in passages; variable water clarity (seasonal); mean salinity approximates 31 parts /1000 yearly; steep forested shoreline topography; rugged intertidal zone; offshore islands and islets occur throughout the resource unit.

Areas With Significant Natural and Cultural Values

Bentinck Island and Eemdyk Passage

*Strong ocean currents

*Protected bays

*Shoals and reefs

*Shingle beaches

*Steep nearshore topography – good zonation of

intertidal habitats

*Kelp forests (over 30 species of algae)

*Shallow high current velocity subtidal ecosystems

*Rocky shore tide pools’Sea and shorebird habitats

*Marine mammals (killer whale, harbour seal, otters, mink, sea lions, porpoises and whales (baleen)

*Historic Indian burial site and historic leper colony grave site and buildings

Race Rocks

*Strong ocean currents

*High tides

*Unique subtidal benthos

*Kelp forests (seasonal)

*Shoals and reefs

*seabird feeding and nesting area

*Marine mammal feeding and resting area

*Marine mammals (harbour seals, sea lions, killer whales, elephant seals, and other cetaceans)

*Whirlpools

*Abundant subtidal marine flora and fauna community assemblages

*Historic lighthouse

*Salmon fishery

Semi-Exposed Outer coast

This marine resource unit has a relatively unsettled climate due to,the influence of the outercoast climatic patterns and frequent southwesterly gales. The shoreline is exposed and experiences pronounced and continuous wave swells and tide surge due to the extended fetch across Juan de Fuca Strait.

The following natural phenomena are characteristic of this resource unit:

Nearshore Rocky Point is subject to strong currents and tide surge; tide range is comparable to transition coast; 7 degC surface water temperature; mean salinity approximates 31 pt/00 yearly; variable water clarity; steep to vertical nearshore in Rocky Point area; protected bays and shallows; narrow intertidal zone; cold water upwellings; pocket beaches; and offshore islands, islets, shoals and reefs.

Areas with Significant Natural and Cultural Values

Swordfish – Church Islands

*Strong ocean currents

*Rich subtidal flora and fauna

*Underwater caves and cliffs

*Surge channels

*Steep nearshore topography (vertical intertidal zonation)

*Waterfowl and seabirds

*Kelp forests (seasonal)

*Salmon fishery

Race Rocks and Juan de Fuca Strait

Shallows at Bentinck Island with Eemdyk Passage in background

*Marine mammals (harbour seals, sea,lions, killer whales

and other cetaceans)

*Coastal geomorphological features

*Unique subtidal benthos (dense populations of Metridium senile in seacave)

*Shoals and reefs

Aldridge Point

*Protected bay

*Interesting geologic formations

*Rocky tide pools

*Sand beaches

*Spectacular headland and steep sea cliffs

*Parkland shoreline

*Rocky and sand subtidal habitats

*Garry oak – arbutus

*Western hemlock forest

*Indian petroglyphs

*Salmon fishery

The land-sea interface in the Park exhibits a wide diversity of landforms and marine communities within a relatively confined geographical area. The areas just outlined, are perhaps the most conspicuous and ecologically sensitive sites in the Park. It is in these areas, where the coastal habitats, marine communities and oceanographic phenomenon achieve their greatest expression.

Small bay at Aldridge Point

Church Hill

3.1.2 Shoreland Resource Units

The shoreland of the park is located in the Coastal Forest and Gulf Islands Biotic Regions. Two shoreland resource units were identified as follows:

1. Gulf Coast Forest

2. Coastal Forest.

Gulf Coast Forest

The vegetation of this resource unit ranges in character from dry, open arbutus – Garry oak parkland to closed canopy forests of western red cedar and grand fir in seepage areas.

The Garry oak occurs in extensive, pure groves in dry areas and where the soil is shallow and rock outcrops frequent. Extensive groves are found at Albert Head, Mary Hill and Rocky Point. The arbutus is more often found singly or in small groves along the coast. The arbutus and Garry oak dominate in dry areas and create a parkland character in much of the shoreland east of Mary Hill.

Valley and upland areas which are subject to periodic. Heavy rains are covered with natural stands of western red cedar, grand fir, red alder and big leaf maple while areas closer to the shore are dominated by shore pine. Sitka spruce is occasionally found on low ground.

Snowberry Symphoricarpos mollis, oceanspray Holodiscus discolor, ninebark Physocarpus capitatus, and choke cherry Prunus virginiana, are a few of the shrub and herbs commonly found in this unit.

Coastal Forest

A small portion of the coastal forest resource unit is located in the western portion of the Park. The wet Douglas-fir borders the western portion of Becher Bay and is dominated by Douglas-fir and western red cedar. In shoreland areas western red cedar is the characteristic tree on sites with abundant seepage water and on alluvial soils it is frequently accompanied by black cotton wood, Sitka spruce, grand fir, red alder and bigleaf maple. Garry oak and arbutus occur in isolated groves. Toward Sooke Peninsula the Garry oak gradually disappears and the parkland character is replaced by coastal forest.

The soils of this biotic community are derived from surface tills deposited by the last glaciation, and the soil types belong to the dystric brunisol, humoferric podsol and.regosol groups.

Dry Western Hemlock Forest at Beechey Head

4. Park Concept

4.1 Park Objectives

The philosophy and objectives for the designation and establishment of Race Rocks National Marine Park are outlined in the Preliminary National Marine Park Guidelines (see Appendix 1).

The primary values of Race Rocks National Marine Park are to be found in the diversity of natural and cultural resources which provide highly significant conservation, scientific and outdoor recreation opportunities.

Race Rocks National Marine Park encompasses a marine region which can be developed and managed for public use and enjoyment. To this end, the Park provides Parks Canada with an opportunity to protect and conserve not only representative species of marine benthos, fishes, waterfowl , seabirds, shorebirds, shoreland and marine mammals but also the respective habitats which are vital to the continuation of each respective species.

Intimately associated with these natural marine features are significant outdoor recreation values. The Park provides the opportunity to introduce to the diving and non-diving visitor the images and ecological systems of the marine world. The intent of the Park is not only the protection and conservation of the marine environment but also the presentation of a rich and

varied experience for the park visitor.

The Park resource unit evaluation and Park design concept outlined in the following sections describe how the above objectives can be achieved.

Becher Bay Marina

Witty’s Lagoon Regional Park

4.2 Park Resource Unit Evaluation

The purpose of this preliminary evaluation section is to utilize the data gained from analyzing the resource units and to summarize the important characteristics that would influence planning decisions in terms of natural and cultural constraints, development constraints, and suitability for use in each resource unit. The accompanying chart briefly describes the basic objectives, use potential and concerns envisaged for each marine and shoreland unit.

For the shoreland resource units, attention is directed only to those areas which have been identified as possessing outstanding representative shoreland features and which are considered as being critical to the overall Park development concept. (see Park development concept page 52). The objectives, use potential and concerns as related to the shoreland units is considered within the context of the respective marine resource units.

Table of resource units, goal, objectives, use potential, management considerations.

4.3 Preliminary Park Design Concept

Concept – Land Base

To complement the marine component it is envisioned that a land bas e(s) will function to support a variety of facilities from which the visitor can be introduced to the Park and from which most park activities will originate. The land base(s) will support a main visitor centre and secondary activity areas. The main function of the centres will be visitor services with the key element being interpretation. This will include: information and interpretive services and educational and recreational programming.

The development of the appropriate land base(s) will require cooperation with federal, provincial and regional agencies and conservation organizations to provide resources, facilities, interpretation and protection for visitor use. Various federal agencies administer lands on Rocky Point, Bentinck Island, Race Rocks, William Head, Albert Head and Esquimalt Lagoon. The designation of these lands as recreation and open space areas now, or sometime in the future, will assist in securing the integrity of key shoreland and intertidal areas which are critical to the overall management, preservation, and future development of Race Rocks National Marine Park.

Park Centre Christopher Point is the area on the shoreland bordering the Park which has the physical and visual characteristics required to accommodate a major visitor centre facility. The site is readily accessible by land and sea and offers a panoramic view of the marine component and adjacent shoreland areas. The semi-protected shoreline provides for the development of excellent docking and access facilities. The rugged shoreline with protected beaches, offshore islands, offshore islets, good underwater visibility and abundant marine life provides the opportunity to develop a wide range of centralized shoreland and marine based interpretive facilities.

The main centre would be designed to accommodate park visitors under all weather conditions. The development of a kaleidoscope of interpretive techniques such as specimen, slide and film displays and possibly in the future underwater tower, underwater cameras and so on would expose the park visitor to the natural and cultural marine history themes of the Park.

From the main visitor centre the visitor can actively participate in onsite activities such as surface boat tours to Bentinck Island and Race Rocks, interpretive walks, shoreline hikes to scenic viewpoints such as Church Hill, and underwater observation.

The centre would also function as the focal point for all diving and underwater activities in the Park.

Albert Head Activity Area

A second activity centre on Albert Head would support an interpretive program on a limited scale. Interpretation would utilize outdoor exhibits and shoreland tours to impart to the visitor the coastal maritime and natural history of the inner coast resource unit. Intertidal walks, beach-combing, marine mammal and bird watching, and general enjoyment of the ocean setting and marine life would replace more common beach oriented activities. Facilities for day-use recreation and overnight camping could be made available to provide a reasonable amount of accommodation for campers close to the main park centre at Christopher Point. A scenic parkway and surface boat facilities would link this centre with the centres at Christopher Point and a second activity area at Aldridge Point.

Aldridge Point Activity Area

A second activity centre at Aldridge Point would permit the park visitor physical and visual access to one of the finest seascape vistas on southern Vancouver Island. The rugged shoreline cliffs, pocket beaches, frequent fogs and storms and the semi-wilderness aspects of the surrounding landscape offers an out in contrast to t he seascape of the inner coast. Exploration and interpretation of a variety of coastal habitats and cultural themes will complement minor day-use activities.

Christopher Point

Eastern portion of Albert Head Peninsula

Park Circulation

The two secondary activity centres could be connected on land via the existing road networks or by a more scenic parkway designed to parallel the coast. The proposed parkway would function to integrate not only the Park activity centres but also existing recreation and historic sites which occur in the shoreland adjacent the Park. Water transport between the main visitor centre and secondary activity areas would be facilitated by tour boats and private cruiser.

4.4 Phasing

The following is a general outline of the proposed phases for development of Race Rocks National Marine Park. These phases do not relate specifically to a given time period but are intended to indicate the necessary priorities to achieve logical development of the Park.

*Establish marine Park boundary and define legislative procedures necessary to control development and use of the Park area and surrounding waters.

*Publication of management recommendations.

*Development of safety facilities, equipment and procedures prior to construction of park centre.

*Acquisition via purchase or lease of the three land base sites – Christopher Point, Albert Head and Aldridge Point.

*Acquisition via purchase or lease of park centre access right of way as shown on preliminary park region concept plan.

*Development of park centre access road, proposed park centre. Parking areas, and associated marine facilities – e.g., dock facilities, interpretive facilities (shoreline trails, boats, etc.), underwater structures

*Development of secondary activity areas, first at Albert Head and second at Aldridge Point, and associated camping and interpretive services.

*Development of shoreland scenic parkway and reconstruction of historic sites as shown on preliminary park region concept plan.

*Extension of marine boundary from Beechey Head to Iron Mine Bay.

4.5 Summary

It is the purpose of this report to point out the outstanding coastal and marine natural and cultural resources and use considerations contained within the project area and the potential that exists for a National Marine Park at Race Rocks. The information contained in this report was obtained from published works and on site investigations. There remains much study and research to do in order to more adequately document the complete resource. General intertidal and sublittoral observations clearly indicate that the project area is worthy of National Marine Park status.

The preliminary proposal presented here does not give full consideration to existing established coastal zone uses in the project area. No doubt, these will have important ramifications on any planning that may occur in the region particularly as it relates to the development of the park centre and activity areas, recreation patterns and types of use in the marine component, Control of access to the marine component and park phasing and development.

The establishment and development of Race Rocks National Marine Park should be guided by a number of planning considerations. These will result from an evaluation of the marine capabilities and development potential. This proposal is an initial attempt at identifying and delineating the major resources of the Park as they relate to the cultural and natural characteristics of the region. The proposal also provides a preliminary resource evaluation and attempts to designate areas for the development of visitor facilities in relation to the sensitivity of the resource base.

Future Outlook

The planning process is unending; the preliminary proposal is a primary step. From this basic plan will hopefully come detailed plans which will more fully consider the many aspects of the Park and its development.

Considerations

Given that the resource base is representative of the Strait of Georgia – Juan de Fuca Marine Region, thoughtful deliberation must be directed to the following considerations:

*The feasibility of creating a National Marine Park in the project area in view of existing established shoreland and marine uses.

*The capability of management programs to deal with environmental disruptions such as major oil spills and/or shoreland and water quality deterioration due to urban industrial and commercial growth in surrounding regions.

*The suitability of the project area to provide the full range of underwater opportunities with safety to all participants without causing serious environmental disruption.

*Within the project area and its contiguous lands a number of jurisdictional bodies are represented. Matters relating to jurisdiction must be fully explored by all parties prior to the designation of the area as a park.

*A re-adjustment of the Park boundaries to maximize management controls while reducing resource conflicts is an appropriate consideration at this time..

a) Scuba-diving at Race Rocks

b) Scientists conducting underwater research at Race Rocks

c) Salmon fishing in Pedder Bay d Intertidal explorers at Witty’s Lagoon

e) Boating in Race Passage , Hiking on Rocky Point

f) Hiking on Rocky Point

NATIONAL MARINE PARKS

Definition: National Marine Parks are ocean areas (sea bed and overlying water column) together with associated landunits, established in order to preserve marine areas of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic Oceans that encompass significant marine ecosystems, themes, and features of biological, oceanographical, geological, recreational, aesthetic, historical and scientific interest.

Objectives

National Marine Parks are established to preserve unspoiled marine areas of national significance; to protect and restore marine areas encompassing significan features warranting preservation; to protect and restore individual species of marine life; to provide opportunities for scientific studies, education, and tourism benefits.

Qualifying Criteria

1 In order to be considered as a potential National Marine Park a marine area must encompass one or more of the following attributes:

(a) Unique – a unique marine area is one which encompasses either rare or “one-of-a-kind” habitat types, biotic associations, oceanographic features, or processes, ecological processes, or historically important ancient wrecks.

(b) Representative – an outstanding representative sample area that is typical of a marine region or marine natural history theme(s).

(c) Aesthetic – Underwater landscapes of outstanding scenic and inspirational value.

In addition, a candidate area for a Marine Park should satisfy the following criteria:

(a) Diverse – the candidate marine area should include several habitat types, biotic associations, oceanographic features and processes.

(b) Natural – Marine areas under consideration should be in a relatively undisturbed condition. Loss of naturalness, however, should not mitigate against inclusion so long as a high degree of restoration is possible.

(c) Critical – when possible, the marine area should include habitat types which are essential for either the entire life histories or important life stages (i.e. feeding, resting and breeding) of marine mammals or birds. Obvious cases are areas where rare or endangered species are present.

(d) Usable – the marine area should provide outstanding opportunities for enjoying marine-oriented activities such as SCUBA diving, surfing, or the observation of marine mammals and seabird life.

(e) Accessible – Public access systems to the marine area are desirable but not critical.

(f) Size – The land and water area in a Marine Park should exceed 10 square miles with larger water quality protection zones surrounding the park.

REFERENCES

Introduction

Barker, M.L. Water Resources and Related Land Uses Strait of Georgia – Puget Sound Basin, Geographical paper no. 56, Lands Directorate, Department of Environment, Ottawa, 1974.

Paish, H. and Associates. A Theme Study of the Marine Environment of the Straits Between Vancouver Island and the British Columbia Mainland. Ottawa. November, 1970.

The Interdepartmental Task Force on National Marine Parks, National Marine Parks Straits of Georgia and Juan de Fuca, Ottawa 1971.

2.1.1 CLIMATE

Department of Transport, Meteorological Division, Ottawa Climatic Data for Periods 1941-1970 Vancouver Island.

Forward, C.N. Land Use of the Victoria Area, British Columbia. Geographical Branch, Department of Energy, Mines and Resources. Ottawa, 1961.

Kerr, D.P. “The Summer-dry Climate of Georgia Basin British Columbia”, Transactions of the Royal Canadian Institute, vol. 29, 1951-1952, pp. 23-31.

W

2.1.2 GEOLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGIC PROCESSES OF THE COASTAL ZONE

Clapp, C.H. “Geology of Portions of the Sooke and Duncan Map-Areas, Vancouver Island, British Columbia”, Geological Survey, Department of Mines, Sessional Paper Number 26, Ottawa, 1914, pp. 41-54.

Clapp, C.H. and H.C. Cooke. Sooke and Duncan Map-Areas, Vancouver Island, Memoir 96, Geological Survey, Department of Mines, Ottawa, 1917.

Day, J.H. et al. Soil Survey of Southeast Vancouver Island and Gulf Islands British Columbia. Report no. 6 of the British Columbia Soil Survey, Research Branch, Canada Department of Agriculture, 1959.

2.1.3 OCEANOGRAPHY

Dodimead, A.J. et al., “Review of Oceanography of the Subarctic Pacific Region”, Intern. North Pacific Fish. Comm. Bull. 13. 1963.

Doodson, A.T. and H.D. Warburg, Admiralty Manual of Tides, Hydrographic Department, Admiralty, London 1941

Department of Environment, Marine Sciences Directorate, Canadian Tide and Current Tables, 1975. Vol. 5, Ottawa

b6

Herlinveaux, R.H. and H.P. Tully, “Some Oceanographic Features of Juan de Fuca Strait”, J. Fish. Bd. Canada. 16(6). 1961.

Pike, G.C. and I.B. MacAskie, Marine Mammals of British Columbia, Fish. Res. Bd. Can. Bulletin 171, Ottawa. 1968.

2.1.4 MARINE LIFE OF THE INTERTIDAL AND SUBTIDAL ZONE

Dobrocky “Seatech” Limited, The Intertidal and Subtidal Macroflora and Macrofauna in the Proposed Race Rocks Marine Park near Victoria, British Columbia. A Report to the National Parks Branch, Ottawa, May 1975.

Kozloff, E.W. Seashore Life of Puget Sound, the Strait of Georgia and the San Juan Archipelago. J.J. Douglas Ltd., Vancouver, 1973.

Ricketts, E.F. and J. Colvin, Between Pacific Tides, revised by J.W. Hedgpeth, Stanford University Press, Stanford California, 1974.

Stephenson, J.A. and A. Stephenson, “Life Between Tidemarks in North America: IV a Vancouver Island, 4. J. Ecology, vol. 49, (1): 1-29.

Stephenson, J.A. and A. Stephenson, “Life Between Tidemarks on Rocky Shores” W.H. Freeman and Company, San Francico, 197?.

2.1.5 MARINE FISHES

Carl, G.C. Some Common Marine Fishes, British Columbia Provincial Museum, Handbook no. 23, 1973.

Hart, J.L. Pacific Fishes of Canada. Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Bulletin 180, Ottawa, 1973.

2.1.6 SHORELAND AND MARINE BIRDS

Godfrey, W.E. The Birds of Canada, National Museums of Canada, Bulletin no. 203, Ottawa, 1966.

Guiguet, C.J., The Birds of British Columbia:__(3) Shorebirds. Handbook No. 8, British Columbia Provincial Museum, 1973.

Guiguet, C.J., The Birds of British Columbia: (9) Diving Birds and Tube-nosed Swimmers. Handbook No. 29, British Columbia Provincial Museum, 1971

Guiguet, C.J, The Birds of British Columbia: (6) Waterfowl. Handbook No. 15, British Columbia Provincial Museum, 1973

Guiguet, C.J, The Birds of British Columbia: (5) Gulls. Handbook No. 13, British Columbia Provincial Museum, 1974.

Munro, J.A. and I. Mct. Cowan. A Review of the Bird Fauna of British Columbia.. B.C. Prov. Mus., Spec, Pub. No. 2: 1-285.

Victoria Natural History Society, Annual Bird Report 1972.

2.1.7 MAMMALS

Bigg, M.A. The Harbour Seal in British Columbia Fish. Res. Bd. Canada. Bulletin 172, Ottawa, 1969.

Guiguet, C.J. “An Apparent Increase in Californian Sea Lion Zaloplus Californianue, and Elephant Seal, Mirouaga Angustirostris, on the coast of British Columbia”, Notes, Syesis, Vol. 4, 1971.

Hannock, D. “California Sea Lion as a Regular Winter Visitant off the British Columbia Coast”. J. of Mammalogy, Vol. 51, No. 3.

Pikee, G.C. and I.B. MacAskie, Marine Mammals of British Columbia, Fish. Res. Bd. Canada, Bulletin 171, Ottawa, 1968.

Seed, A., Toothed Whales in-Eastern North Pacific and Arctic Waters, Pacific Search, Seattle Washington, 1971

Seed, A., Baleen Whales in Eastern North Pacific and Arctic Waters, Pacific Search, Seattle Washington,

1972.

Seed, A., Seals, Sea Lions, Walruses in Eastern North Pacific and Arctic Waters, Pacific Search, Seattle Washington, 1972.

2.1.8 SHORELAND BIOTA

Hosie, R.C. Native Trees of Canada, Canadian Forestry Service, Dept. of Fish. And Forestry, Queen’s Printer, Ottawa, 1969.

Rowe, J.S. Forest Regions of Canada, Dept. of Environment, Canadian Forestry Service. Ottawa 1972.

2.2 CULTURAL RESOURCES

Begg, A. History of British Columbia, William Briggs, Toronto, 1894.

Duff, W. The Indian History of British Columbia, Volume 1: The Impact of the White Man. Anthropology in British Columiba, Memoir No. 5, 1964.

Forward, C.N. Land Use of the Victoria Area, British Columbia, Geographical Paper No. 43, Geographical Branch, Dept. of E.M.R., Ottawa.

Hawthorn, H.B. et al, The Indians of British Columbia, University of Toronto Press. 1958.

Hazlitt, W.C. British Columbia and Vancouver Island, S.R. Publishers Ltd., New York, 1966.

Nickolson, G. Vancouver Island’s West Coast 1762-1767, Morriss Printing Co., Victoria, 1962.

Ravenhill, A. The Native Tribes of British Columbia, King’s Printer, Victoria, 1938.

Rogers, F. Shipwrecks of British Columbia, J.J. Douglas Ltd. Vancouver, 1973.

Memorandum on File

OTTAWA, Ontario KlA OR4

October 29, 1976.

Meeting with Mr. A. Fairhurst and Mr. D. Ross,, Province of British Columbia Department of Conservation-and Recreatio

October 19, 1976 — Race Rocks National Marine Park Proposal

On the morning of Tuesday October 19, 1976 I met with Mr. A. Fairhurst and Mr. D. Ross, members of the Coastal Planning Section, Conservation and Recreation Branch, British Columbia and the Federal-Provincial Task Force for the Establishnent of Race Rocks National Marine Park in the vicinity of Victoria,, British Columbia,

Up until this meeting no correspondence had transpired between the members of the Task Force since Mr. C, Mondor, Co-ordinator, Area Identification, sent a copy, of the report entitled “Race Rocks National MarinePark: A Preliminary Proposal”, on March 10, 1976 to Mr. Fairhurst. This report was prepared by the Marine Themes Section,, Parks System Planning Division in compliance with the original terms of reference of the Task Force.

The purpose of the October 19th meeting, therefore, was twofold:

(1) to solicit from the Provincial members of the Task Force their initial impressions and comments an the above document.

(2) to establish what steps needed to be taken to successfully complete the terms of reference of the Task Force.

Some time was spent in considering the preliminary proposal, with the

Province making the following comments:

(1) the concept as it deals with the identification and use of marine resources is well developed.

(2) existing resource uses in the foreshore and backshore areas of the proposal requires more emphasis in the report.

(3) the potential social-economic Impact and how it relates to park development on the area requires further emphasis.

Several comments are in order with respect to points two and three. It was recognized at the on-set of writing the report, that existing resource uses in the area should receive minor consideration. The main objective of the report was to assess the natural resources of the area and how they could best he preserved, used and interpreted. Nevertheless it should be pointed out that existing resource uses in the park proposal area are well documented under separate cover and need only to be inserted In the appropriate section of the report when the need arises.

Point three was accepted as a valid point by all members. However, Mr. Fairhurst suggested that prior to commencing phase two of the Task Force duties, i.e. completion of points two and three as an intricate part of the planning process for the Park., a copy of the preliminary –resource document should be sent from the Director of the National Parks Branch, namely Mr. Steve Kun to Mr.. Tom Lee, Director of the Provincial Parks Branch. This was requested as no official communication at the Director level had transpired, as it relates to the review of the preliminary resource concept plan.

Mr. Ross suggested that both Directors should be made aware of the scope of the preliminary concept plan; that points two and three were considered prior to commencement of the first phase of the project that these aspects have yet to be incorporated in the final report. It was therefore agreed by the Task force members at the meeting that the following course of action be pursued:

(1) a copy of the preliminary resource document entitled “Race Rocks National Marine Park: A Preliminary Proposal”, be reviewed at the Director level.

(2) the Task Force awaits a directorate comments and approval in principle of the preliminary report prior to commencement of phase two and three.

(3) If such approval is obtained that a meeting of the Task Force be convened in early January to discuss future action as it relates to the Director directions.

A letter is presently being drafted for Mr. Kun’s signature in compliance with point above.

The matter rests.

Duncan Hardie,

Marine Themes Section.

Parks System Planning Division,

National Parks Branch

cc. Steve Kun

cc. John Carruthers

cc. Claude Mondor