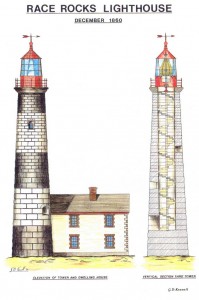

On Boxing Day 1860 the magnificent Imperial Light on the treacherous Race Rocks Islets was lit for the first time. Since then a succession of dedicated lightkeepers have tended the light as a vital navigation aid for ships transiting Juan de Fuca Strait and bound for Victoria, Vancouver, Seattle and the Inside Passage.

The urgent need for a light on Race Rocks had become obvious to the British Admiralty in the early 1850s. The new American light at Cape Flattery marked the southern entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait. Ships made the turn to starboard and found themselves navigating an inland waterway with variable winds and dangerous currents. At Race Rocks a tide race swirls past the rocky outcrops at speeds of up to 8 knots.

Located one nautical mile from the southern point of Vancouver Island, Race Rocks is only 12 nautical miles from the American shore, Race Rocks is swept not only by the strong tides but also the surging waves of the Pacific.

1860s Victoria was emerging as an important port. Captain George Richards,RN. of aboard the survey ship HMS Plumper reported that “a great want which is felt by all vessels coming to Vancouver’s Island of a light on the North shore on the Race Islands or Rocks.” The decision to construct the Admiralty’s first lights on the West Coast at Fisgard at the entrance to Esquimalt harbour and at Race Rocks was soon made.

The construction of Race Rocks light was a remarkable undertaking. Granite was cut and numbered in Scotland and then shipped as ballast for assembly at Race Rocks. Throughout the summer of 1860 the massive stones were barged from the harbour to the Race and assembled using timber derricks and scaffolding largely by the crew of the 24-gun wooden screw frigate Topaze.

Three days before the light was lit, tragedy struck. If there was ever any doubt about the need for the lighthouse structure the loss of the 385 ton sailing ship Nanette proved it. Without the warning the Nanette ran hard aground on Race Rocks and was a total loss.

The Nanette’s mate William McCullogh wrote in the ship’s log: “At 8 o’clock saw a light bearing N by W [this must have been the new light at Fisgard lit only two months earlier] Could not find the light marked on the chart. At 8 1/2 o’clock it cleared somewhat, and then saw the point of Race Rocks the first time, but no light. Called all hands on deck, as we found the ship was in a counter current, and drifting at a rate of 7 knots toward the shore. We made all possible sail, but to no avail.”

With the assistance of the construction gang the crew of the Nanette found shelter although the lightstation boat was also lost. HMS Grappler was able to rescue the crew from Race Rocks the next day. The Nanette’s cargo of machinery, trade goods and rum, valued at over $160,000, was strewn across the rocks. This prize attracted eager local salvors. One ambitious crew perished when their over loaded canoe capsized off Albert Head tossing five men, a woman and her baby into the sea.

Soon after the light went into service, Race Rocks’ distinctive black and white stripes were painted on the tower by the first lightkeeper George Davies to improve it’s visibility. Although the light was a great improvement on clear nights when it was visible for 18 miles the hazards of Race Rocks were still very real in the fogs that shroud the islets for up to 45 days a year.

Notable wrecks at Race Rocks include the SS Nicholas Biddle sunk in 1867, the Swordfish wrecked in 1877, the SS Rosedale sunk in 1882, and the Barnard Castle, a coal freighter en route from Nanaimo to San Francisco that struck Rosedale Rocks in 1886.

In 1892 the Department of Marine and Fisheries installed two compressed air fog horns at Race Rocks. The Department had taken over operation of lighthouses from the British Admiralty in 1871 when British Columbia joined the Dominion of Canada. Despite the addition of the powerful horns tragedies continued at Race Rocks.

In 1896 the SS Tees crashed ashore,in 1901 the Prince Victor was wrecked. The worst disaster occurred on the night of March 24, 1911 when the ferry Sechelt , bound for Sooke from Victoria found herself fighting a fierce westerly gale. The captain decided to turn back for the shelter of Victoria. Caught in a beam sea the Sechelt capsized and took her crew and 50 passengers with her to the bottom of Race Passage.

In 1923 the liner Siberian Prince went aground within a mile of Race Rocks light without ever hearing the fog horn. Two years later, the Holland America liner Eemdijk also ran aground in the same location. Again the ship’s crew reported they did not hear the horn. The tug Hope was lost with her crew of seven while attempting to salvage the Eemdijk . In 1927 Race Rocks was the first station on Canada’s West Coast to be fitted with a radio beacon. This helped to prevent further tragedy.

The issue of the reliability of the lightkeepers and the fog horns was finally resolved in 1929 when the Hydrographic Survey ship Lillooet investigated the so called silent zone and found an unusual deflection of the sound as a result of the location of the horns. The horns were moved to a separate tower and for the first time were truly useful.

Their living conditions for Race Rock lightkeepers were difficult. The original stone house at the base of the light tower was drafty and damp. In southeast gales, rain penetrated the cement joints in the structure.

On Christmas Day 1865, the first keeper George Davies and his wife Rosina were awaiting the visit of her brother, sister-in-law. As their skiff approached, with the Davies family watching and waving from the station, a tide rip only 20 feet from the jetty swept the small boat away, capsizing it and dumping the shocked passengers and their gifts into the water. The station had no boat at this time and the visitors perished. The new year was no better for Davies. During the winter of 1866 George became seriously ill. The Union Jack flew at half mast at the station as a signal of distress for nine days but to no avail. George Davies died shortly before Christmas 1866.

In 1867 Thomas Argyle was appointed as Chief Keeper of Race Rocks Light at an annual salary of $630. His wife Ellen was retained as matron at $150 and two assistant keepers were hired at a salary of $390 each. Supplying the station was difficult as it involved rowing out from Victoria but at least the Admiralty paid up to $900 a year for supplies. The employment conditions for the keeper of Race Rocks deteriorated after 1871 when the new Dominion Government took over. Argyle’s salary was cut to a paltry $125 and he was expected to pay for his own assistants and supplies. Argyle took to the sea to supplement his food supplies. His family had grown considerably as six children were born to the Argyles at Race Rocks. He was known to dive into the frigid waters around the station in search of abalone, scallops and mussels.

It seems that Argyle’s luck changed in 1885. The Victoria Colonist newspaper reported that he paid for his supplies with gold sovereigns. When Argyle died 30 years later at the age of 80 he had still not exhausted his supply of coins. It would appear that his diving expeditions resulted in the discovery of sunken treasure.

Argyle served at Race Rocks foryears and retired in 1888. One son was drowned at age 19 when returning from Victoria with a friend. Another son Albert took over as temporary keeper until a new appointment was made in 1889. According to descendants of Argyle they would not allow him to stay on as keeper because he was not married!

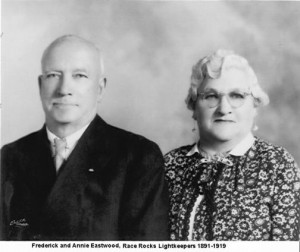

Appointments to government jobs were always closely linked with political patronage. The appointment of W.P. Daykin who came from Sand Head station was clearly influenced in this way. Daykin served for three years before moving on to Carmanah Light Station on the outside coast. Frederick Eastwood, his wife and three children moved to Race Rocks in 1891. When Eastwood hired two Japanese assistants, he was charged with dereliction of duty when the local MP Colonel E. G. Prior wrote to the Minister that “for a long time past this lighthouse has been in the charge of two Japanese instead of a white man.”

Minister Louis Davies fired the Japanese. “The Department was not desirous to encourage in any way the employment of these men,” he decided.

A second keeper, Arthur Anderson, was lost in 1950 when he left his wife and two children to obtain supplies ashore. He never returned. His skiff turned up empty along the American shore near Port Angeles.

In the early 1960s , the old stone house attached to the bottom of the tower was destroyed under the “efficiency policies” of the time by the Canadian Coast Guard. In 1997 the last lightkeeper left Race Rocks lightstation after it was automated.

I

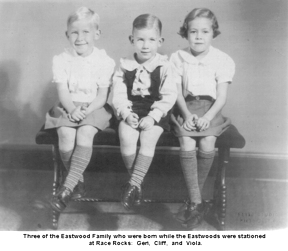

I Geri continues: “I wanted to send you a picture of Great Grampa Eastwood and Grandma Eastwood so I”ve attached it for you, (see picture above,).. also attached is this one of Auntie Geri, Cliff & Viola (mom) when they were young .”

Geri continues: “I wanted to send you a picture of Great Grampa Eastwood and Grandma Eastwood so I”ve attached it for you, (see picture above,).. also attached is this one of Auntie Geri, Cliff & Viola (mom) when they were young .”