by Peter F. Olesiuk and Michael A. Bigg (~1984)

MARINE MAMMALS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA

Peter F Olesiuk and Michael A. Bigg, (~ 1984)

Introduction

Seals and sea lions, also known as pinnipeds, are a familiar sight in coastal waters off British Columbia. These mammals lead partly a terrestrial and partly a marine existence. Their streamlined bodies, specialized flippers and insulating layer of blubber allow them to travel and forage at sea with ease. However, unlike dolphins, porpoises and whales, pinnipeds require land to bear and suckle their young and to rest.

The waters off B.C. are home to five species of pinnipeds representing two families. These are the Phocidae, or true seals, which includes the northern elephant seal and harbour seal, and the Otariidae or eared seals, which includes the northern fur seal and the Steller and California sea lions.

The true seals are characterized by the absence of external car flaps and by their short, fur-covered flippers. On land they cannot easily raise their head and shoulders and thus tend to remain prostrate. The rear flippers cannot be rotated forward, so while on land they move in a caterpillar-like fashion, rhythmically undulating their bodies with synchronized dragging strokes of the front flippers. In water, they swim by alternating side-to-side strokes of their rear flippers, while the front flippers aid in steering.

Members of the Otariidae, on the other hand, have small external ear flaps and large hairless flippers. On land the front flippers are used for body support to raise the head and shoulders. The rear flippers can be rotated under the body, which allows these animals to amble over land using both the front and rear flippers. While swimming, they use their front flippers like wings to propel and steer themselves.

Seals and sea lions in B.C. have evoked a great deal of interest over the years. At one time, they were utilized extensively for food and clothing by coastal natives. Between the early 1900s and late 1960s, they were hunted commercially and their populations regulated by predator control programs. However, increasing public sympathy toward marine mammals prompted changes in management and in 1970, harbour seals, northern elephant seals, and Steller and California sea lions were protected under the federal Fisheries Act. The northern fur seal has been protected since the early 1900s under the terms of the Interim Convention on Conservation of North Pacific Fur Seals, an international agreement involving Canada, Japan, the Soviet Union and the United States.

Since 1970, several species have become more abundant off our coast, causing concern among fishermen, who often view these animals as competitors for fish and as a source of damage to their gear and catch. It is not surprising, therefore, that many fishermen support culling programs that would maintain populations at low levels. However, this solution conflicts with the goals of many others, who believe populations should be left to reach a natural balance. Resolution of these differing perspectives presents a dilemma for fisheries managers in B.C., and in many other parts of the world.

This pamphlet provides the most recent scientific information on the status of seals and sea lions in B.C. It describes the general biology, trends in abundance and feeding habits of species that occur on the B.C. coast. The conflicts that arise with commercial and sport fisheries are also discussed.

Northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris)

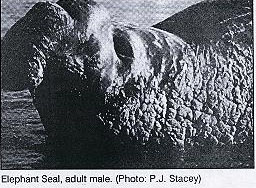

The Northern elephant seal is the largest species of pinniped inhabiting the Northern Hemisphere. Adult females grow to about 3 m (10 ft) in length and may weigh up to one tonne (2200 lbs). Adult males are larger and may attain a length of 5 m (16 ft) and weigh as much as 2 tonnes (4,400 lbs). Males may also be distinguished from females by their pendulous snouts. Pups weigh about 30 kg (65 lbs) at birth and are weaned in about a month, by which time they have tripled in weight. The pelage of both sexes is a uniform light brown.

Northern elephant seals are found in the northeast Pacific between California and southern Alaska. Nineteenth century sealers operating off the coasts of California and Mexico hunted these seals to the brink of extinction, and by the turn of the century the species had been reduced to a few hundred individuals. Since then the population has made a remarkable recovery to near historic levels of about 100,000 and is continuing to increase.

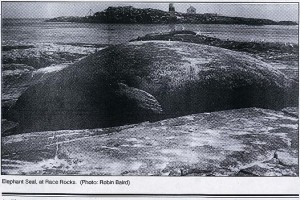

During December to March, most northern elephant seals congregate on islands and beaches off California and Mexico to bear their young and mate. By the end of March the pups have been weaned and all animals begin to disperse from the rookeries to forage on the continental slope. Pups and adult males tend to move north along the coast, occasionally as far as Alaska. Relatively few reach B.C. Adults rarely haul out in B.C. and are usually seen resting vertically in the water with their massive head and neck extending above the water like a large log. However, weaned pups, which weigh about 70 kg (150 lbs.), occasionally come ashore to rest. Because of behavior, they are often thought to be sick.

Northern elephant seals are capable of diving for up to 45 minutes and to a depth of 806 m (2,600 ft). They prey mainly on ratfish, sharks, cusk eels and squid. This seal has not been a problem for fishermen in B.C.

Northern elephant seals are capable of diving for up to 45 minutes and to a depth of 806 m (2,600 ft). They prey mainly on ratfish, sharks, cusk eels and squid. This seal has not been a problem for fishermen in B.C.

(PHOTOS) Northern elephant seals have likely been the source of more than one sea monster sighting. Photos courtesy of Kenneth Balcomb, Center for Whale Research, Friday Harbour, Washington.

Harbour seal Phoca vitulina

The harbour seal is a relatively small phocid. Males and females are similar in size and as adults attain a length of 1.2-1.6 m (4-5 ft) and usually weigh 60-80 kg (130-180 lbs). Pups weigh about 10 kg (22 lbs) at birth and double their weight during a 4-6 week suckling period. Males live up to 20 years, while the life span of females extends to 30 years. The pelage varies in color from nearly black with light spots to nearly white with dark spots.

The harbour seal is a relatively small phocid. Males and females are similar in size and as adults attain a length of 1.2-1.6 m (4-5 ft) and usually weigh 60-80 kg (130-180 lbs). Pups weigh about 10 kg (22 lbs) at birth and double their weight during a 4-6 week suckling period. Males live up to 20 years, while the life span of females extends to 30 years. The pelage varies in color from nearly black with light spots to nearly white with dark spots.

Harbour seals occur in most temperate coastal areas of the North Atlantic and North Pacific Oceans, and also enter navigable rivers and lakes. Although no precise figures are available, the northeast Pacific population is estimated to number at least 350,000.

These seals are typically seen in small groups resting on tidal reefs, boulders, and sandbars, but they can sleep under-water on the ocean bottom if no suitable haulout site is available. The population is traditional in the particular sites utilized as haulouts. There is little social organization in these colonies. Unlike many other pinnipeds, harbour seals do not congregate on rookeries but breed throughout most of their range. The birth season lasts about 2 months and varies from February-March to August-September, depending on location. In southem B.C., births occur in July-August and during May-June in northern B.C. Pups are usually born on tidal reefs or sandbars and begin to swim immediately. Although local movements associated with breeding and feeding may occur, harbour seals are otherwise non-migratory.

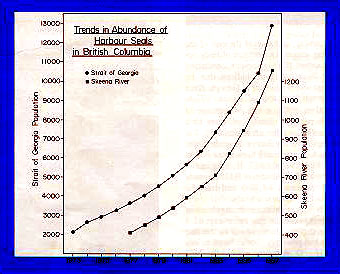

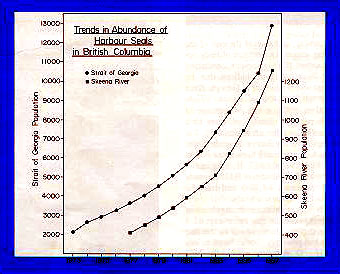

The abundance of harbour seals has been monitored in Georgia Strait since the mid 1960s. Counts are usually conducted from small aircraft at times when most of the population is hauled out. In Georgia Strait about 90% of the animals haul out on low tides, on calm days, in the morning, and toward the end of the pupping season.

The pelage of harbour seals varies considerably in color and pattern. Harbour seal populations in B. C have been increasing in all areas surveyed by DFO. The increases, believed to be occurring province-wide, represent the recovery of populations that had been depleted by bounties and hunting.

The pelage of harbour seals varies considerably in color and pattern. Harbour seal populations in B. C have been increasing in all areas surveyed by DFO. The increases, believed to be occurring province-wide, represent the recovery of populations that had been depleted by bounties and hunting.

Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) surveys conducted under these conditions indicate that the harbour seal population in Georgia Strait has grown from about 2,100 in 1973 to 12,500 in 1987, a rate of increase of 12.4% per year. Similar increases have occured in all other areas censused. For example, in the lower Skeena River counts have increased from about 400 in 1977 to 1,250 in 1987. It is estimated that the total population in B.C. currently numbers about 65,000 and may be approaching historical levels.

This recent increase in numbers in B.C. represents the recovery of a depleted population, which in the late1960s had probably been reduced to less than 15,000. A bounty offered by DFO for each seal killed between 1913 and 1964 reduced populations to about half historic levels. Harbour seals were also intensively hunted for their pelts between 1962 and 1969. The population could not withstand this additional hunting and declined sharply during the mid 1960s.

Researchers at the Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo recently began examining the impact of the growing harbour seal population on fisheries. Data are presently being collected on diet, seasonal movements and abundance in conflict areas to establish the extent to which seals interfere with fishing activities and their impact on important fish stocks, such as salmon and herring.

One of the main topics now being studied is the amount of salmon consumed by harbour seals. The amount of food eaten by a seal depends on its size and sex, the season and the caloric content of the prey. On average, harbour seals consume about 1.8-3.2 kg (4-7 lbs) of fish daily. At present not enough is known about the diet of harbour seals to accurately estimate the amount of salmon eaten. Preliminary findings indicate that in most localities, harbour seals prey mainly on a wide variety of small fishes that occur in shallow water around reefs. These include sculpins, small flatfishes and rockfishes, greenlings, smelts and perches. During winter their diet consists mainly of hake and, to a lesser degree, herring. However, salmon may constitute an important part of the diet in some rivers and estuaries while salmon are spawning.Harbour seals also create problems for fishermen by removing salmon from gear. Gillnetters and sport fishermen experience the greatest losses.

Harbour seals create problems for commercial fishermen by removing and damaging salmon in gillnets. Harbour seals also take salmon from the lines of recreational fishermen.

Harbour seals typically occur in small groups on tidal reefs (above) but large herds occur at the mouths of major rivers (left).

Northern fur seal Callorhinus ursinus

Adult male northern fur seals are much larger than females, attaining a length of 1. 9m (6 ft) and weight of 200 kg (450 lbs) compared to 1.3 m (4 ft) and 35 kg (80 lbs) for females. Pups weigh 4.5-5.5 kg (10-12 lbs) at birth and are nursed for 4 months, during which time they increase 2-3 fold in weight. Females can live to about 25 years whereas males rarely live longer than 15 years. The pelage of both sexes is greyish brown and includes a dense layer of underfur.

The northern fur seal is found in off-shore waters throughout the North Pacific Ocean from the latitudes of southern California and southern Japan into the Bering and Okhotsk Seas. The eastern North Pacific stock numbers about 900,000 seals. This stock has declined in recent years, for reasons which are not clear. One likely cause is increased mortality of juveniles many of which drown each year from entanglement in plastic debris, such as discarded nets and packing bands. Two other stocks, with a combined population size of about 400,000 seals, are found off the Asian coast.

Fur seals inhabiting the eastern North Pacific congregate on the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea during June to October to give birth and mate. When animals leave the rookeries in November they disperse widely throughout the eastern North Pacific, but tend to be most concentrated over the continental shelf. Most adult females and a few juveniles migrate to California and pass south through B.C. waters in early winter and north in late spring. Some individuals remain off the B.C. coast during winter and spring, but few come closer than 10 miles to shore. Most adult males remain in the Gulf of Alaska during the non-breeding season.

Northern fur seal

The northern fur seal has been hunted commercially for its fur since the late 1700s. Most seals were taken on rookeries, although many were also taken at sea during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Victoria was an important port for these pelagic sealing operations. For most of this century only young males, aged 3-5 years, have been harvested on the rookeries. Under the terms of the Interim.

Above: Northern fur seal bull (rear), cows (middle), and pups (front) during the breeding season. In many species of pinnipeds males are larger than females, probably because of their polygamous breeding customs.

Northem ,fur seals inhabiting the northeast Pacific gather on the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea each summer to give birth and mate.

Convention on Conservation of North Pacific Fur Seals, Canada received 15 per cent of the skins from harvests of the Pribilof Islands and Asian rookeries. However, the Convention expired in 1984 and only subsistence sealing is now permitted on the Pribilof Islands.

As part of Canada’s obligations under the Interim Convention, the reproductive biology, diet, and food requirements of this species were studied extensively at the Pacific Biological Station during 1958-80. Northern fur seals feed mainly on small schooling fishes. In waters off B.C., 20 % of the diet is salmon and 43 % herring. The amount of food consumed varies with season, but adult females typically eat about 2.5 kg (5.5 lbs) of prey daily. However, the total amount of fish consumed off B.C. cannot be precisely determined because of the difficulty in estimating the number of seals wintering off our coast. Few fishermen in B.C. consider fur seals to be a serious problem.

daily. However, the total amount of fish consumed off B.C. cannot be precisely determined because of the difficulty in estimating the number of seals wintering off our coast. Few fishermen in B.C. consider fur seals to be a serious problem.

Entanglement of fur seals in fishing debris (above) and packing bands (below) may be responsible for recent population declines.

Entanglement of fur seals in fishing debris (above) and packing bands (below) may be responsible for recent population declines.

Steller sea lion Eumetopias jubatus

Steller sea lions are the largest member of the Otariidae. Adult males reach 3 m (10 ft) in length and weigh 450-1,000 kg (1,000-2,200 lbs) whereas the smaller females are 2.4 m (8 ft) long and weigh 180-230 kg (400 – 500 lbs). Pups weigh about 20 kg (45 lbs) at birth and may be nursed for more than a year. The life span of males is about 20 years and that of females about 30 years. The pelage consists mainly of coarse guard hairs and is usually tan in color.

Steller sea lions are the largest member of the Otariidae. Adult males reach 3 m (10 ft) in length and weigh 450-1,000 kg (1,000-2,200 lbs) whereas the smaller females are 2.4 m (8 ft) long and weigh 180-230 kg (400 – 500 lbs). Pups weigh about 20 kg (45 lbs) at birth and may be nursed for more than a year. The life span of males is about 20 years and that of females about 30 years. The pelage consists mainly of coarse guard hairs and is usually tan in color.

The Steller sea lion occurs along the coastal rim of the North Pacific Ocean, from California to the Bering Sea and Kurile Islands. The species tends to remain within a few miles of shore, but is occasionally seen as far as 130 km (80 miles) offshore. Although juveniles have been found up to 1,500 km (900 miles) from their place of birth, adults are largely non-migratory. The total population numbers about 200,000 with most occurring in the Gulf of Alaska. However, populations in Alaska have recently been declining inexplicably, and are now only half the size they were in the 1950s.

The Steller sea lion occurs along the coastal rim of the North Pacific Ocean, from California to the Bering Sea and Kurile Islands. The species tends to remain within a few miles of shore, but is occasionally seen as far as 130 km (80 miles) offshore. Although juveniles have been found up to 1,500 km (900 miles) from their place of birth, adults are largely non-migratory. The total population numbers about 200,000 with most occurring in the Gulf of Alaska. However, populations in Alaska have recently been declining inexplicably, and are now only half the size they were in the 1950s.

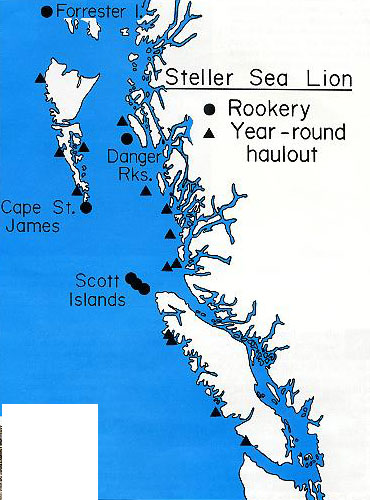

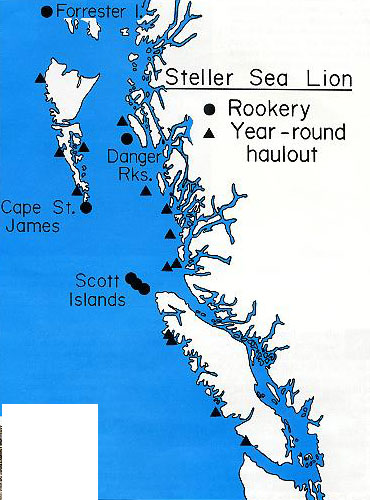

During June and July most of the population gathers on rookeries to breed. In B.C., rookeries are situated at Cape St. James, North Danger Rocks and on the Scott Islands. Animals tend to return to the rookery on which they were born. Some adults and juveniles are also found on sites known as year-round haulouts during the breeding season. In late summer and fall individuals on rookeries disperse locally along the coast to numerous wintering sites.

Aerial censuses conducted during the breeding season indicate that the population in B.C. is currently about 7,000 (including 1,100 pups) and has changed little since the mid 1960s. The current population represents only about one-third the number present at the turn of the century. The reason for the decline was extensive kills between 1912 and 1968. During that time, DFO staff made annual trips to rookeries and haulouts to kill sea lions for predator control. Adults were also commercially harvested on rookeries for mink food.

Why the population in B.C. has not recovered appreciably since it was protected in 1970 is not clear. Competition with Steller sea lions breeding at Foffester Island in Alaska, a few km north of the B.C. border, may be a factor. The Forrester Island stock increased from a few hundred animals in the 1920s to about 6,000 by the 1970s. In fact, almost twice as many pups are now born on Forrester Island as on all rookeries in B.C. Thus, the combined breeding populations for B.C. and southeast Alaska may now be close to historic levels.

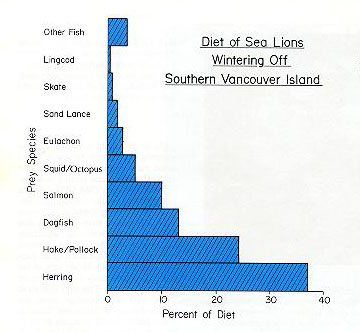

Fishermen have long been concerned over the impact of Steller sea lions on commercially valuable fish stocks. On average, females consume about 5-10 kg (11-22 lbs) and males 10-20 kg (22-45 lbs) daily. During the breeding season, Steller sea lions feed predominantly on octopus and a variety of fish, mainly rockfish. During the non-breeding season they prey mainly upon schooling fishes such as herring, hake, pollock, dogfish, and salmon. Overall, salmon constitutes only a few per cent of their diet.

Steller sea lions also create problems for fishermen by interfering with fishing activities. Some individuals apparently learn to follow commerical trollers and remove salmon from their lines. Sea lions also occasionally pilfer salmon and herring from gillnets and may inflict considerable damage to gear in the process.

Steller sea lion bull (right), pup (middle), and cow (left) showing the difference in size between sexes. Because males must staunchly defend breeding territories, they fast and may lose 200 kg (450 lbs.) during the 2 month breeding season.

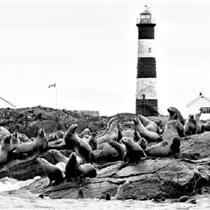

Province-wide censuses are usually conducted when animals are congregated during the breeding season. Shown here is a portion of the Forrester Island rookery just north of B. C. which has grown dramatically in size over the last 50 years.

While the remaining animals are relegated to year-round hautouts . During the non-breeding season animals disperse to numerous wintering sites along the coast.

While the remaining animals are relegated to year-round hautouts . During the non-breeding season animals disperse to numerous wintering sites along the coast.

California sea lion Zalophus californianus

The California sea lion is smaller and darker than the Steller sea lion. Adult males are about 2.25 meters (6.5-8 ft) long and weigh 200 – 400 kg (450-900 lbs) whereas females are 1.4-1.7 meters (4.5-5.5 ft) and 70 – 110 kg (150-250 lbs). Pups weigh about 8 kg (18 lbs) at birth and may nurse for up to a year. The pelage is usually dark brown and appears almost black when wet. Mature males develop a patch of fight colored fur on the crest of their head.

The California sea lion is smaller and darker than the Steller sea lion. Adult males are about 2.25 meters (6.5-8 ft) long and weigh 200 – 400 kg (450-900 lbs) whereas females are 1.4-1.7 meters (4.5-5.5 ft) and 70 – 110 kg (150-250 lbs). Pups weigh about 8 kg (18 lbs) at birth and may nurse for up to a year. The pelage is usually dark brown and appears almost black when wet. Mature males develop a patch of fight colored fur on the crest of their head.

There are three populations of California sea lions: the largest population numbers about 120,000 and breeds off the coasts of California and Mexico; another population of 20,000-50,000 breeds on the Galapogos Islands; and a small population, perhaps now extinct, was known to breed off Japan. Large kills off California and Mexico during the 1800s depleted that population and reduced its range. However, the population has been increasing since the turn of the century and may now be approaching historic levels.

Only adult and sub-adult male California sea lions occur in B.C., mainly during winter months. Between May and August most animals congregate on rookeries off the coast of California and Mexico to pup and mate. At the end of the breeding season animals leave the rockeries. Females and juveniles remain in California and Mexico during the nonbreeding season. Adult and sub-adult males tend to travel north, venturing as far north as central Vancouver Island. They arrive in B.C. in September-October and depart in April-May.

The number of California sea lions wintering off southern Vancouver Island has grown dramatically in recent years. Prior to the 1960s this species was rarely seen here, but by the early 1970s about 500 were present. Numbers increased to about 1,500 by the early 1980s, peaking at 4,500 in 1984. Numbers have since stabilized at about 3,000. The expansion of California sea lions into B.C. is probably a result of the recovery of the breeding population off California. The warm El NiÒo currents in the early 1980s and the recovery of local herring stocks may also have attracted more animals to B.C.

California sea lions wintering off southern Vancouver Island mix extensively with Steller sea lions. The impact on fisheries here is thus being examined for both species combined. The number of Steller sea lions wintering off southern Vancouver Island has increased slightly from about 700 in the early 1970s to about 1,200 currently. It is unclear whether this increase represents a redistribution of Steller sea lions that breed on local rookeries or whether Steller sea lions are being displaced northward from California and Oregon by the expanding population of California sea lions.

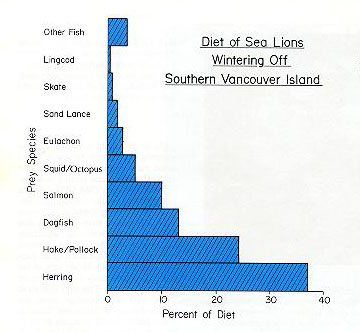

The increase in the number of sea lions wintering off southern Vancouver Island raised many concerns over their impact on local salmon and herring fisheries. Between 1982 and 1985 DFO collected extensive data on the abundance, distribution and feeding habits of these animals. Preliminary analysis of these data indicate that the wintering population feeds mainly on schooling fishes such as herring, hake, pollock and dogfish. Herring make up about 35 per cent of the diet and approximately 2,400 tonnes are consumed annually. This represents about 15 per cent of the average annual roe herring harvest off Vancouver Island in recent years. Salmon comprise about 10 per cent of the diet and 600 tonnes are consumed annually, representing less than I per cent of the commercial salmon landings in B.C.

Sea lions wintering in B.C. are also a problem during the short herring fishery. Animals may swim through the fragile gillnets, tearing large holes in them, and occasionally get into purse seines.

Male California sea lions (left) can be distinguished from a male Steller sea lion (far right) by their darker pelage, smaller size, light fur on the crest of their head, and honking bark as opposed to the Steller sea lion’s deep growl.

Male California sea lions (left) can be distinguished from a male Steller sea lion (far right) by their darker pelage, smaller size, light fur on the crest of their head, and honking bark as opposed to the Steller sea lion’s deep growl.

In areas where no suitable haulout site is available, sea lions may rest in rafts. The flippers are often held out of the water, perhaps to minimize heat loss.

Recent studies into the feeding habits of sea lions wintering off southern Vancouver Island indicate that they prey mainly upon mid-water schooling fishes.

Recent studies into the feeding habits of sea lions wintering off southern Vancouver Island indicate that they prey mainly upon mid-water schooling fishes.

The diet of seals and sea lions can be evaluated by examining undigested remains in scats. Shown here are salmon, dogfish, hake, and skate teeth (top row, left to right) and salmon, dogfish, hake, and herring vertebrae (bottom row, left to right).

Management Policy

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans is responsible for the management and conservation of marine resources including seals and sea lions. The goals of management are to conserve these resources and to utilize them in the best interest of all Canadians. Management policy must balance the diverse and sometimes conflicting interests of Canadians.

For the first half of this century, management of seals and sea lions in B.C. focused on maintaining populations at relatively low levels by culling and hunting for meat and pelts. This kept competition for fish and interference with fishing activities at a low level. In the 1960s a greater interest developed in the preservation of natural resources and controversy arose around the hunting of whales and seals. Strong opposition to the killing of marine mammals emerged.

In 1970 regulations made under the Fisheries Act were amended such that the killing of sea lions, harbour seals and northern elephant seals required a license from the Minister of Fisheries. Since virtually no licenses were issued, this allowed some species, like the harbour seal and California sea lion, to become more abundant in B.C. The presence of more seals and sea lions in B.C. means that there are more animals for tourists to view in their natural habitat and that visibly reassures people that they are not endangered. On the other hand, the increases have raised concern among fishermen and fisheries managers over the impact on fishing gear, catches and on fish stocks, particularly salmon. The conflict of interests makes the management of seals and sea lions considerably more complex than in the past.

Appropriate balancing of the interests depends on information on the actual impact of seals and sea lions on fish stocks and the extent of damage to gear and catch. Research on seals and sea lions in B.C. being conducted by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans is providing this biological information to permit improved assessment of the social and economic implications of various management policies. The assessment process will also require input from the fishing industry, recreational fishing interests, conservation groups and other interested parties.

Suggested Reading

Haley, D. (ed.) 1976. Marine Mammals, 2nd edition. Pacific Search Press, Seattle. 256p.

Pike, G.C. and I.B. MacAskie. 1969. Marine Mammals of British Columbia. Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Bulletin 171 54p.

Ridgway, S.H. and R.J. Harrison (eds.) 1981. Handbook of Marine Mammals. Vol. 1. The walrus, sea lions, fur seals and sea otter. Academic Press, London. 235p.

Ridgway, S.H. and R.J. Harrison (eds.) 1981. Handbook of Marine Mammals. Vol. 2. Seals. Academic Press, London. 359p.

prepared by Peter F Olesiuk and Michael A. BiggPacific Biological Station, Nanaimo, B.C.Department of Fisheries and Oceans

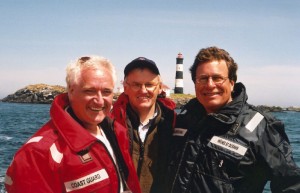

On January 19 2007,Prime Minister Stephen Harper and two federal cabinet ministers, Gary Lunn and John Baird pose with Glenn Darou beside a scale model of the energy generating turbine installed at Race Rocks in September of 2006.

On January 19 2007,Prime Minister Stephen Harper and two federal cabinet ministers, Gary Lunn and John Baird pose with Glenn Darou beside a scale model of the energy generating turbine installed at Race Rocks in September of 2006. B.C. critical for Tory majority, Harper says Peter O’Neil, Vancouver Sun; Files from CanWest News Service Published: Saturday, January 20, 2007

B.C. critical for Tory majority, Harper says Peter O’Neil, Vancouver Sun; Files from CanWest News Service Published: Saturday, January 20, 2007 Putting ‘green’ toward going green Edward Hill, Peninsula News Review Jan 24 2007

Putting ‘green’ toward going green Edward Hill, Peninsula News Review Jan 24 2007