|

|

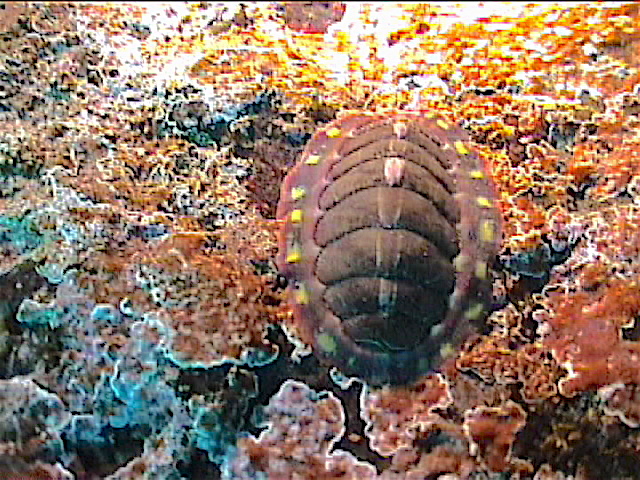

| Cryptic Coloration of Abalone |

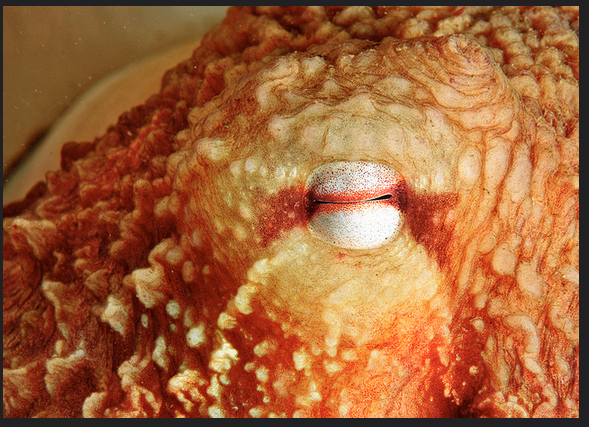

Associated organisms with abalone.

|

Domain Eukarya

Kingdom Animalia

Phylum Mollusca

Class Gastropoda

Subclass Prosobranchia

Order Archaeogastropoda

Suborder Pleurotomariina

Family Haliotidae

Genus Haliotis

Species kamtschatkana

Common Name: Northern Abalone

Paulina and the PC Divers go in search of abalone for our population tagging program. The opportunity arises to demonstrate the escape response of the Northern Abalone, when it is presented with a Pycnopodia, the giant sunflower star.

Scott Wallace did research in 1997 and 1998 at Race Rocks with Pearson College divers. He studied the population dynamics of the Northern Abalone, Haliotis kamtchatkana. His research was done as part of a PhD thesis in Resource Management from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. In May of 2000, he returned to Race Rocks for a dive with Garry and Hana and an interview with Stephanie Paine and Director Julia Nunes for the Discovery Channel. In this video he demonstrates the measurement technique he used in his research

Link to Abstract of Scott’s Paper

Wallace, Scott, S. 1999, Evaluating the Effects of Three Forms of Marine Reserve on Northern Abalone Populations in British Columbia, Canada. Conservation Biology, Vol 13 No 4, August, 1999, pages 882-887.

An article by Scott Wallace:

Out of Sight, Out of Mind, and Almost out of Time out of sight out of mind–mpa

n 1998, we began a long term research program, initiated by Dr. Scott Wallace, on the population dynamics of the Northern Abalone

(Haliotis kamtschatkana).

For several years, the Pearson College divers monitored the population. In this video, Pearson College graduate Jim Palardy (PC yr.25) explains the process.

Carmen Braden and Garry find a Northern Abalone exposed at low tide in June in the intertidal zone of the east side of Race Rocks. They talk about its adaptations and the problem of overharvesting which has resulted in the endangered status.

This abalone was filmed by Felix Chow as it was rasping off diatoms from the glass wall of the aquarium. A small tongue or radula scrapes the algae from the walls.

General information:

Northern or Pinto abalones (Haliotis kamtschatkana) belong to the class of mollusks having a shell that consists of one piece. The genus they belong to is Haliotis, which means “sea ear” and refers to the flattened shape of the shell.

Description:

Description:

Pintos are the smallest abalones and they are commonly about 4 inches long, however the biggest individuals can grow as big as 6 inches long (12 cm). The shell is oval or rounded with a large dome towards one end; it is also irregularly mottled and narrow. The colour of the shell exterior is mottled greenish brown with scattered white and blue. The shell has a row of respiratory pores through which the abalone takes in water and filters dissolved oxygen from the surrounding water with its gills. Water that passes through the body leaves through the respiratory holes carrying away waster from the digestive system. Pinto abalones have from 3 to 6 open holes in their shells. The shape of these respiratory holes is oval and they are raised. The colour of the pinto abalones’ epipodium is mottled greenish tan or brown. The tentacles are thin and the colour of them can vary from yellowish brown to green. Abalones’ muscular foot has a strong suction power that permits the abalone to clamp tightly to rocky surfaces.

Habitat:

Pinto abalones have definite preferences in locations and habits. Pinto abalones range from Sit ka, Alaska to Monterey, California. The only member of the genus is likely to be found in the Puget Sound region., on the open coast of Vancouver Island and Washington. Farther south pinto abalones become strictly sub tidal. Pinto abalones can be found clinging to rocks in kelp beds along open coastal environments that have a good water circulation. Their habitat is between the low inter tidal zone and sub tidally down to 70 feet (18 meters depth).

Life cycle:

The life cycle of an abalone begins from an egg. Abalone female releases millions of eggs, but only about 1% (or even less) of the offspring survive the many challenges they have to face before maturity. The eggs turn into a free living larva and then after drifting with the currents about a week the abalone larva settles to the bottom and begins to develop the adult shell form.

Predators:

Abalone have many predators. They get eaten by other animals (crabs, lobsters, octopuses, starfish, fish and snails) and crushed to the rocks by strong waves. The sea otter was traditionally one of the most significant predators of abalones, although they have not yet moved into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, from the re-introduction several years ago to northern Vancouver Island.

Nutrition:

Pinto abalones, as all abalones, are herbivores. They use their large, rough radulas (“tongues”) to scrape pieces of algae and other plant material from the rock surfaces. The adult abalone feeds on loose pieces of algae drifting in water. Abalones prefer large brown algae; mainly different kind of kelps and seaweed. The colour banding on many abalone shells is caused by the changes in the type of algae that the abalone has eaten.

Threats:

Pinto abalones used to be subject to sports and commercial fishery . They suffered from over harvesting and habitat loss and poaching. There is now a permanent closure on all abalone fishing on the B.C. Coast. For the Pacific North West Coast First Nations People, the beautiful shells of abalone were used for jewelry and abalone also were a seafood delicacy. They occur sub tidally and only in remote areas.

See the Abalone measurement and statistics exercise at RaceRocks:

http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/research/abalone/abalonemeas.htm

See our abalone exercise for middle school.

References Cited:

Kozloff, Eugene N., Marine Invertebrates of the Pacific Northwest, University of Washington Press, Seattle and London, 1996.

Kozloff, Eugene N., Seashore life of the Northern Pacific Coast, University of Washington Press, Seattle and London, 1996.

Meglitsch, Paul A., Invertebrate Zoology; second edition, Oxford University Press, 1972.

Snively, Gloria, Exploring the Seashore in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon, Gordon Soules Book Publishers Ltd., Vancouver/London, 1981.

http://www.pacificbio.org/ESIN/OtherInvertebrates/NorthernAbalone/NorthernAbalone_pg.html ( available at this URL in 20101)

http://www.sonic.net/~tomgray/describe.html

Other Members of the Phylum Mollusca at Race Rocks.

The Race Rocks taxonomy is a collaborative venture originally started with the Biology and Environmental Systems students of Lester Pearson College UWC. It now also has contributions added by Faculty, Staff, Volunteers and Observers on the remote control webcams.

The Race Rocks taxonomy is a collaborative venture originally started with the Biology and Environmental Systems students of Lester Pearson College UWC. It now also has contributions added by Faculty, Staff, Volunteers and Observers on the remote control webcams.