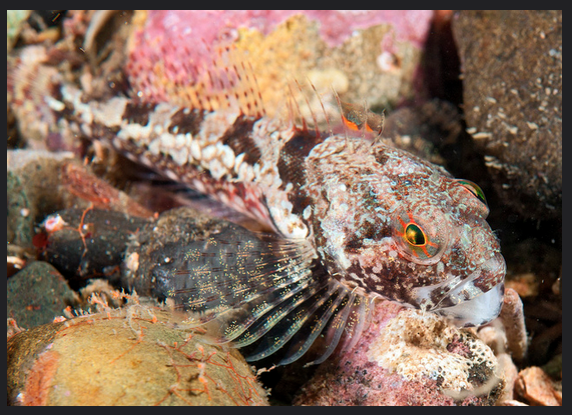

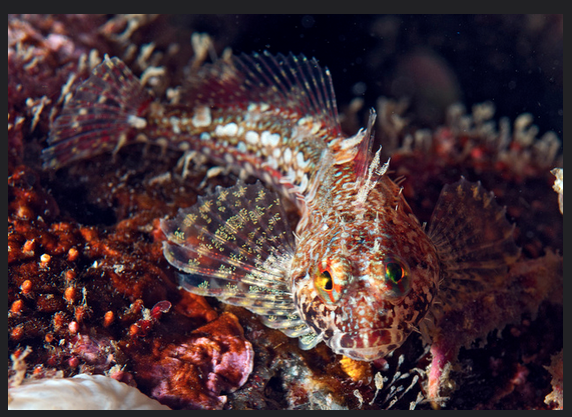

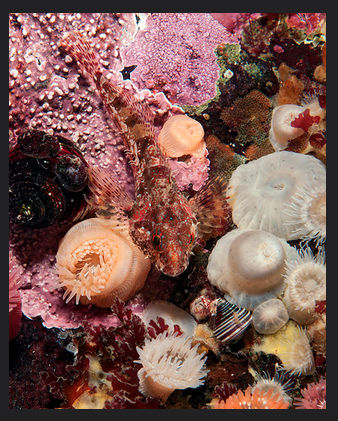

Physical Description:

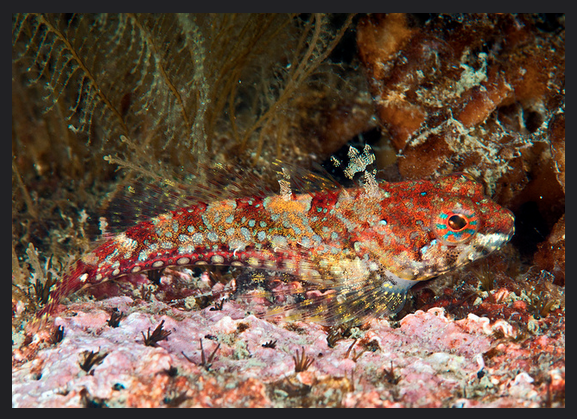

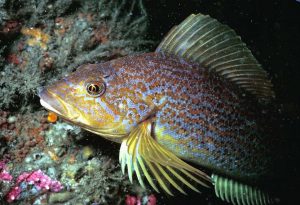

At sea, they are coloured metallic blue on back, with silvery sides. Also have irregular black spots on back, upper fin and lower dorsal fin. Gums are white at base of teeth and fins are tipped with orange.

Maturing males in fresh water will have bright red sides, with their head and back coloured bright green, and often dark on their bellies. Females are less brightly coloured, with bronze to maroon coloured sides.

Fry is orange with dark spots concentrated on back and fins.

Can also be identified by their “hook-nose” jaws; their upper jaw hooks down slightly towards the lower jaw.

Coho salmon can grow to be a length of 79cm and weigh 14kg.Global Distribution:

Coho salmon spawn in coastal streams from Northern Japan to the Anadyr River in Siberia, and from Monterey Bay in California to Point Hope in Alaska. They can be found at sea from Japan and Korea to the Chukchi Sea and southeastward to Baja, California. They have a center of abundance between Oregon and southern Alaska.

Humans have introduced Coho salmon to the Great Lakes with enormous success. Attempts to introduce them to the Atlantic coast of North America between 1901 and 1948 failed miserably.

Habitat:

Coho salmon are extremely adaptable; they occur in nearly all accessible bodies of fresh water and utilize nearshore and offshore environments during lifecycle. However, they prefer to stay close to shore to avoid predators and will not be found deeper than 30m.

Coho salmon will not be found in temperatures lower than 6.5°C or higher than 21°C, and those that live off of the southern United States have been known to migrate north as the temperature rises.

Coho salmon prefer to spawn in streams with low velocity, shallow water and small gravel. Most Coho fry stay in the stream where they are born for a over a year in schools that are located in quiet areas free of current.

Reproduction:

Coho salmon, like all salmon, are anadromous fish, which means that they spend most of their life feeding at sea, but return to fresh water to breed (and always return to the same place where they were born and lived as fry). Coho salmon are also oviparous, which means that they reproduce by the female laying eggs and the male fertilizing them after they leave the female’s body.

Because of the large spread distribution, spawning occurs over a very large period (between October and March). Generally, more southern spawning occurs later during this time period. More specifically, spawning in British Columbia occurs in October and November. The closest spawning river to Race Rocks is the Goldstream river just north-west of Victoria.Spawning occurs at night. A female will dig a nest, called a redd, and deposit an average of 2 400 to 4 600 eggs (but up to 7 600). The male will fertilize the eggs as she lays them. A female can make several redds, and usually deposits all of her eggs between them.

The eggs develop during winter and hatch into larvae in early spring. The warmer the temperatures, the faster the eggs develop. After hatching, the larvae stay under the gravel for a few weeks and then emerge as fry.

The spring following this, they will start their journey towards the sea. Females and some males will return to spawn after three years. Most males (known as jacks) will return after two years to mate.

Coho salmon die 3-24 days after mating.

Feeding:

As larvae, they feed off of their yolk (which is still attached to them). They do not emerge from the gravel as fry until this source of nourishment has run out. It is then that they start eating aquatic insects, zooplankton, small fishes, and the remaining carcasses of the salmon that died after spawning.

At sea, Coho salmon feed on fishes like herrings, anchovies, sand lances and rockfishes, and invertebrates such as krill and squid.

Coho salmon only feed during the day.

Predators:

Humans are a Coho salmon’s biggest threat. They are considered prize sport fish because of the ‘memorable’ fight that they put up, and make up for half of the recreational salmon catch in British Columbia. Coho salmon have also developed a reputation for being particularly tasty, making them the perfect victim of the commercial fishing industry. It is estimated that the Coho population off of California is 6% of what it was in the 1940s due to the fishing industry. And British Columbia still ‘wins’ for the highest catch per year in North America!

In addition to humans, Coho salmon are eaten by some larger fishes, as well marine mammals like seals, orcas and white-sided dolphins.

Interesting fact:

All salmon undergo smoltification upon entry to the sea in order to live in sea water. This process works both backwards and forwards: it allows them to leave the sea for fresh water, and to leave fresh water for the sea.

However, some Coho salmon have been known to live in fresh water their whole lives, and these freaks of nature are known as residuals.

Domain Eukarya

Kingdom Animalia

Phylum Chordata

Subphylum Vertebrata

Class Actinopterygii

Order Salmoniformes

Family Salmonidae

Genus Oncorhynchus

Species kisutch

Common Name: coho salmon

Resources:

1. Coho Salmon Facts. 1996. Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission. November 11, 2005. http://www.psmfc.org/habitat.edu_Coho_facts.html

2. Coho Salmon: Wildlife Notebook Series. 1994. Alaska Department of Fish & Game. November 11, 2005. http://www.adfg.state.ak.us/pubs/notebook.fish.Coho.php

3. Deutsch, A. Coho Explained. 2005. Pacific Coast Salmon Coalition. November 11, 2005. http://www.Cohosalmon.com/Coho_explained.htm

4. Hart, J.L. Pacific Fishes of Canada. Ottawa, ON: Information Canada, 1973.

5. Love, Milton. Probably More Than You Want to Know About the Fishes of the Pacific Coast. Santa Barbara, CA: Really Big Press, 1996.

References: Andy Lamb and Phil Edgell: “Coastal fishes of the Pacific Northwest”

J.L Hart: “Pacific fishes of Canada”

The Race Rocks taxonomy is a collaborative venture originally started with the Biology and Environmental Systems students of Lester Pearson College UWC. It now also has contributions added by Faculty, Staff, Volunteers and Observers on the remote control webcams. March 15 2009-

The Race Rocks taxonomy is a collaborative venture originally started with the Biology and Environmental Systems students of Lester Pearson College UWC. It now also has contributions added by Faculty, Staff, Volunteers and Observers on the remote control webcams. March 15 2009-