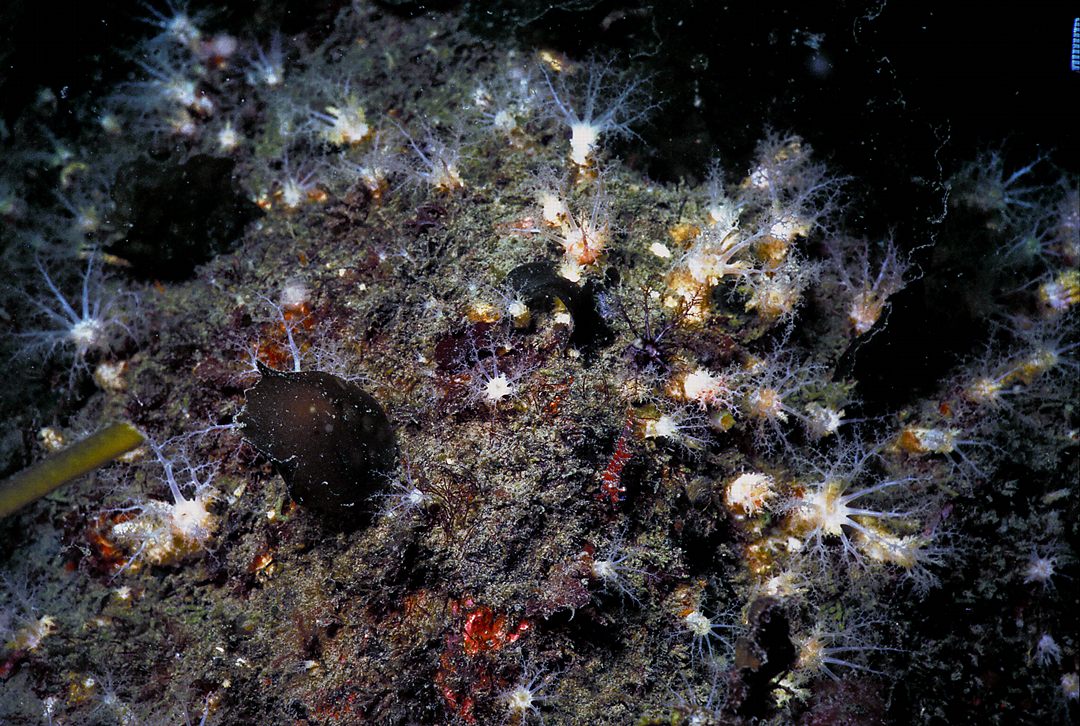

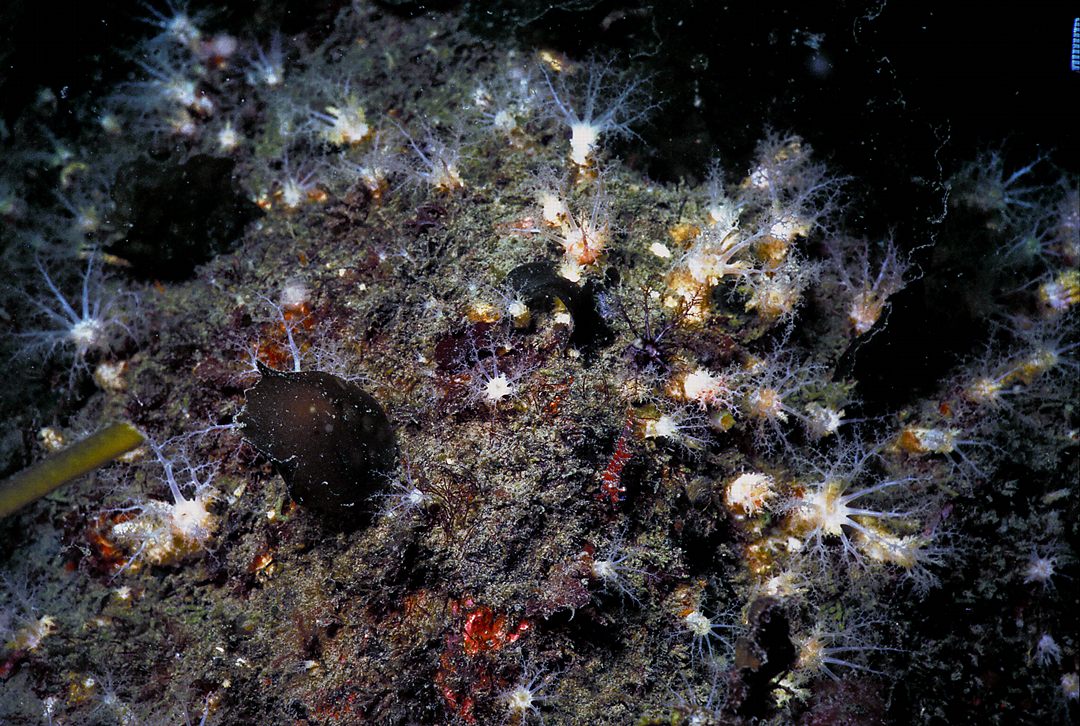

Here are the tentacles extended on a cluster of Eupentaca.Their bodies are hidden. Photo by Dr.A. Svoboda

Here are the tentacles extended on a cluster of Eupentaca.Their bodies are hidden. Photo by Dr.A. Svoboda

GENERAL DESCRIPTION

Eupentacta quinquesemita is stiff to touch due to abundant calcareous ossicles in the skin and tube feet. The body grows 4-8 cm in length. The non-retractile tube feet give it a spiky look. It has five rows of tube feet (four tube feet in width) with smooth skin between. The two ventral feeding tentacles are smaller than the other eight. This character is useful for identifying this species when only the tentacles are visible. The expanded tentacles are creamy white with tinges of yellow or pink at the bases.

Skin ossicles: numerous large, porous, ovoid bodies dominate the ossicles but among them are small, delicate baskets. The latter are important in differentiating this species from Eupentacta pseudoquinquesemita.

HABITAT

They are fairly common under the rocks and in cervices, low intertidal zone on rocky shores; common on concrete piles and marina floats in Monterey harbor, Vancouver (British Columbia) to Morro Bay (San Luis Obispo. Co). High densities of this species occur in strong currents. Juveniles (up to 1 cm) settle among hydroids and small algae in high current areas and on floating docks.

REPRODUCTION

Eupentacta quinquesemita is a suspension feeder. It spawns from late March to mid May. The female produces eggs greenish in color, 370 to 416 um diameter: the male releases sperm, and fertilization takes place in open water. The yolky egg develops into a non-feeding evenly ciliated larva. In culture, the larva grows to the armoured stage in 11 to 16.5 days.

PREDATORS

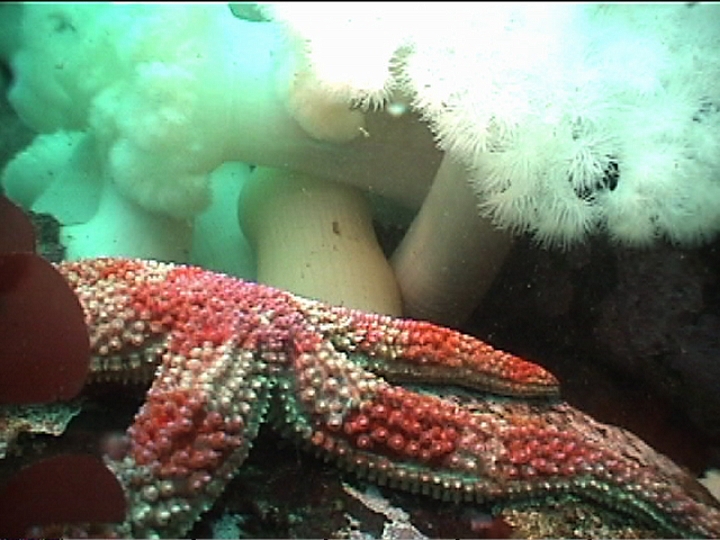

The predators of Eupentacta quinquesemita are: the Sun Star (Solaster stimpsoni), the Sunflower Star (Pycnopodia helianthoides), the Six-armed Star (Leptasterias hexactis) and the Kelp Greenling (Hexagrammos decagrammus).

BIOTIC ASOCIATION

The internal parasite, Thyonicola americana, a shell-less wormlike snail, attaches elongated coils of eggs to the intestine of E. quinquesemita. The larvae are released into the intestine and probably scape through the anus. Any parasites that are ejected by evisceration perish.

FEEDING

Is by shovelling of sediment into the mouth and digesting the microfauna within. No direct feeding is required. Is omnivore.

DomainEukarya

Kingdom Animalia

Phylum Echinodermata

Class Holothuroidea

SubclassDendrochirotacea

Order Dendrochirotida

Family Sclerodactylidae

Genus Eupentacta

Species quinquesemita

Common name White sea cucumber

REFERENCES

Lambert, P. 1997. Sea Cucumbers of British Columbia, Southeast Alaska and Puget Sound. UBC Press, British Columbia Canada. 166 pages

Morris, R., P. Abbott, and E. Haderlie.1980. Intertidal Invertebrates of California. Standford University Press, Stanford, California. 690 pages.

Kozloff, E. 1996 . Seashore Life of the Northern Pacific Coast. Fourth Edition. University Of Washington Press. Seattle and London. 370 pages.