By Robin W. Baird

Elephant Seals occur fairly frequently on -the B.C. coast, but few people recognize them when they do see them. Adult males only rarely come ashore, and while in the water animals of all ages and both sexes spend up to 90% of their time beneath the surface. Their behaviour while at the surface makes them very difficult to notice as well: at first glance they appear similar to a large, partially waterlogged log floating vertically at the surface (commonly termed a deadhead). Unlike real deadheads, which may bob up and down with waves or a swell, Elephant Seals just sink slowly out of sight after several minutes, and may not surface again for half an hour or more. In fact, the maximum recorded dive length (actually, for the similar southern Elephant Seal) is exactly two hours (Hindell et al. 1989), and they usually only surface for two to three minutes before repeating their dive. They do this day and night, for days, weeks and even months on end, even sleeping underwater. As well, they are generally solitary except during the breeding season, and only breed off the California and Mexican coasts.( now-2006, also at race Rocks)

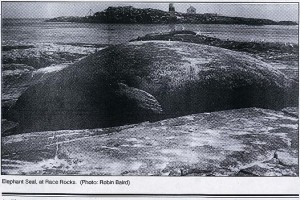

Elephant Sea[, at Race Rocks. (Photo: Robin Baird)

Moulting occurs at different times throughout the year depending on the age and sex of the animal. Juvenile Elephants Seals (about 1.5 – 2 metres in length) moult in the spring. In B.C. this is the age class most frequently seen hauling out to moult.

Moulting in Elephant Seals not only involves losing the hair, but the entire outer layer of skin, often in great sheets, and frequently the animals suffer from skin infections, resulting in bleeding. These infections are usually of low level and do not typically seriously harm the animal. When Pinnipeds (seals, sea lions and walruses) come out of the water their eyes continuously water to keep them moist, an adaptation that protects their eyes but also contributes to their sick appearance.

Most people assume that Elephant Seals are much larger than the juveniles which typically haul out in this area, but at this stage they appear fairly similar to Harbour Seals. In fact, confusing juvenile Elephant Seals with Harbour Seals occurs frequently. Despite the fact

that Elephant Seals can be approached closely by people on foot, have watering eyes, and due to their epidermal moult have skin that is literally falling off and sometimes infected, these are normal conditions and the animals are in reality quite healthy. There have been several occasions around Victoria in the last year where such Elephant Seals have been mistakenly identified as sick Harbour Seals and this has resulted in the inadvertent euthanization of the animals.

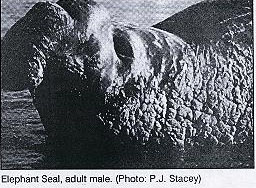

The differences between juvenile Elephant Seals and Harbour Seals are fairly obvious once you know what they are. Unlike Harbour Seals, Elephant Seals have no spots on the skin, rather they are a uniform greyish brown or yellowish colouration, although while moulting, their skin appears very patchy. The rather “swolled’ snout, and the horizontal crease just below the nostrils are characteristic of Elephant Seals, and a harbinger of the bulbous nose that comes with adulthood for the males. The hind flippers of Harbour Seals are relatively straight along the trailing edge, while Elephant Seals have a inverted U-shaped curve to the trailing edge of their hind flippers. Many of the animals are also tagged on the hind flippers, while very little work has been done in tagging Harbour Seals.

More accurate identification of Elephant Seals will both prevent the types of accidents mentioned above from occurring, and will assist research in terms of trying to monitor the numbers of Elephant Seals in the province. If population numbers in B.C. mimic the increase seen in their breeding range off California, Elephant Seals may become a more common sight off our coast. Such an increase should not worry those concerned with potential conflicts with fisheries, as the diet of the Elephant Seal consists mainly of species largely ignored commercially, such as Ratfish, Dogfish and other sharks, various species of skate, some squid, Cusk Eels, and occasionally deep water, slow swimming fish.

Records of Elephant Seals around southern Vancouver Island have been increasing in the last year, although it is not known if this is due to an actual increase in their presence, or just that more people are aware of the differences between Harbour Seals and Elephant Seals, and are reporting their presence.

We have been attempting to respond to most reports of hauled out Elephant Seals, or of 1arge sick Harbour Seals that you can walk right up to”. We try to check for tags, record age and if possible sex (not an easy task since you’d have to roll the distress.

Some animals are branded as well as tagged, although they lose the brand when they moult. Many are double tagged, with a different number on each tag, so both left and right hind flippers should be checked if an animal is found.

A summary of records of Elephant Seals in B.C., including information on their origin (for tagged individuals), is presently being compiled by Victoria resident Marcel Gijssen and others. Dr. Burney Le Boeuf is responsible for tagging many of the animals born near Ano Nuevo, a site in central California between Santa Cruz and San Francisco.

Anyone observing elephant seals in B.C. can assist with this project by reporting sightings to me at the following address:Department of Biological Sciences,Simon Fraser University, address now not applicable

References:

Hindell, M.A., Slipp, D.J., and Burton, H.R. 1989. Diving Be-haviour and Foraging Ranges of Southern Elephant Seals (Mirounga leonina) From Macquire Island. Page 29 in Abstracts of the Eighth Biennial Conference on the Biol ogy of Marine Mammals, December 1989, Pacific Grove.

6The Victoria Naturalist Vol. 47.2 (1990)