From August to November, a group of California Sea Lions hauls out on the shore to the East of the Docks with a few even staying on the docks. They get very used to the boats docking there and are often joined by a few large Northern sea lions as well. The constant barking sound comes from the California Sea lions, and the low growls are from the Northerns.”

Macs at Work-By David Ferris– in MACWORLD

QuickTime Conservation

By David Ferris

Three cameras film live, continuous shots in QuickTime of lolling sea lions, dive-bombing pigeon guillemots, and spectacular sunsets. Web visitors can even control Camera One to make it zoom in on sights.

Welcome to Race Rocks, Garry Fletcher says. Use the Web to visit the windswept islands off the coast of British Columbia, Canada. Watch and listen.

Then stay away.

It took Fletcher 20 years to persuade the Canadian government to protect Race Rocks, a group of small islands that jut from the north shore of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The islands, Canada’s southernmost point, teem with sea lions, seabirds, and anemones.

Fletcher, a biology instructor at Lester B. Pearson College in Victoria, British Columbia, established racerocks.com last year. His idea: if he brought Race Rocks to the masses via streaming media, maybe the masses wouldn’t come by, spooking seals and seagulls and banging boat anchors on the reefs.

Three cameras film live, continuous shots in QuickTime of lolling sea lions, dive-bombing pigeon guillemots, and spectacular sunsets. Web visitors can even control Camera One to make it zoom in on sights.

Feeds from each of the stationary cameras go to an iMac running Sorenson Broadcaster software. One Power Mac G4 streams archived video, and another is used to edit footage in iMovie and Sorenson. Meanwhile, Camera One’s remote features run on a Mac 7300.

Racerocks.com has a mobile Webcasting unit: a Sony digital video camera connected via FireWire to a PowerBook G3 equipped with an AirPort card. Footage can be shot anywhere in the islands and surrounding waters, transmitted to an AirPort Base Station on the biggest island, and boosted with an external antenna.

Fletcher and his students even wired the island for sound by sticking a stan- dard Mac desktop microphone out of a window. “We’ve put it in a plastic bag,” Fletcher says. “It’s amazing how it picks up the seal sounds and the gull sounds.”

Fletcher’s students use this mobile filming system during the summer months to create live Webcasts of tide pools and other ecosystems. And divers have used the same camera — connected by cable to a support boat — to capture images of sea lions cavort-ing in the deep.

A thousand visitors go to racerocks.com each week for the sights and sounds. But they’re lucky Fletcher’s setup doesn’t deliver one of the sensations of Race Rocks: the smell. “It can be fairly ripe at times, especially when the sea lions pile up next to the docks,” says Fletcher.

Race Rocks Marine Protected Area Update May 6 2001

Racerocks.com continues to reach to the far corners of the world as more and more people become aware of this extraordinary ecosystem and the opportunity to discover it electronically.(over 100,000 visitors in the past year) Garry Fletcher, our Educational Director, has attended conferences in New York, California (twice) and in the near future plans to go to Halifax. In each case we have featured live webcasts from Race Rocks with video from both above and below the surface to the conference site. On March 17, 2001 we completed the first underwater webcast in which in addition to video one of our student divers spoke directly to the conference participants from underwater at Race Rocks. This was possible thanks to a fabulous, locally developed, wireless underwater communications system created by Divelink.

A wireless internet feed from Race Rocks is now possible for eco-tourism vessels in the MPA. Visitors to the MPA can now establish wireless internet access aboard their vessel from most locations within the MPA. This allows guides to download real time video streams showing activity in the MPA including underwater video from the display tanks on the island. In addition, visitors can have access to archived video of marine life, First Nation’s activities and more recent history stored on the Race Rocks server. If you are interested in more information about the equipment required and how you could subscribe to this service please contact Angus Matthews.

Eco-guardians Mike and Carol Slater continue to do an outstanding job for us all as our resident caretakers of the island and equipment. We are grateful to Mike and Carol for their dedication and commitment to Race Rocks and it’s many residents. It is also reassuring to know that their watchful eyes are always looking out for us.

Should you need to contact them they are usually monitoring VHF 16 or 68.

Site restoration has continued on the island over the winter. In late April the Coast Guard finished flying out the last of the concrete from the dykes that surrounded the old tank farm. This has returned another large portion of the island to a natural state. We are working with BC Parks to establish a plant life inventory of Great Race Island. We have modified the Coast Guard’s old lawn mowing compulsion to allow more of the natural grasses and vegetation to take over the island. A small perimeter is maintained around the buildings for fire safety and Mike and Carol of course maintain their traditional kitchen garden.

BC Parks has assumed ownership of the area of Great Race Island that was previously leased to the Coast Guard. A small area around the light tower and solar panels has been retained by the Coast Guard as they are still responsible for the automated navigational aids. All the remaining infrastructure on the island has been given over to BC Parks. Pearson College has entered into a 30 year park use permit agreement with BC Parks to continue to operate the facility as we have for the past four years.

Serious financial challenges lie ahead. Now that the federal Millennium Partnership funding that established racerocks.com has been exhausted we are receiving no financial support for the operation of the Race Rocks MPA from any government. We are hopeful that BC Parks and DFO which established the MPA will respond positively to our application for them to provide a contribution of $50,000 each towards operating costs. Pearson College has undertaken to raise the balance required to cover the $150,000 annual budget. We hope that the eco-tourism industry will consider assisting us in the future as a demonstration of the commitment you have to environmental protection and Canada’s first Marine Protected Area. See $ave Race Rock$

Please excuse our questionable flag etiquette! One of the pitfalls of joint federal/provincial jurisdiction is they both want their label on the product. At the request of our current MLA we are now flying both the BC and Canadian flag on the same mast on the island. Until the funding arrangements are worked out it is simply prudent to do so!

The special operational guidelines for Race Rocks established by the eco-tourism operators have been largely respected and we greatly appreciate the individual commitment vessel operators have made to following them. We are now working on better cooperation from other organisations such as the Navy and education of the general public. Our proceedure is to log all infractions and contact the operator or their owner directly to advise them of a difficulty. The level of cooperation and voluntary compliance from the eco-tourim sector has been outstanding and we appreciate it a great deal.

Operator training for the 2001 season is now occurring in many eco-tourism organisations. Many of your operators have received special training about the MPA in the past. If the number of new operators warrants it, we have offered to host a training session ashore at Race Rocks in the near future. Please contact Dan Kukat if you think this is necessary.

Marine life at the Race features several elephant seals again this year and the sea lion/ harbour seal population looks fairly strong for the time of year. Already a number of harbour seal pups have been born, and this emphasizes the need for cautious navigation through the area as they are very vulnerable. Serious bird nesting activity is starting so our activity on the island and access is now being limited. Chick survival on the island was very poor last year largely due to what appeared to be starvation. Hopefully more of the usual food sources will return this year.

We look forward to another successful season of protection and education at the Race. Thank you for all you do to share this experience with an appreciative public.

Angus Matthews

Director of Administration and Special Projects, Lester Pearson College

Oil Tank Farm Restoration

Background:

The automation and the de-staffing of the former Coast Guard-Operated Light Station on Great Race Rocks happened in 1997. This would normally have left the island without a generator, as all buildings and equipment were to be removed when the automated foghorn and the light were installed, there was theoretically no need for a generating station.

The automation and the de-staffing of the former Coast Guard-Operated Light Station on Great Race Rocks happened in 1997. This would normally have left the island without a generator, as all buildings and equipment were to be removed when the automated foghorn and the light were installed, there was theoretically no need for a generating station.

Lester Pearson College decided to hire the former keepers, Mike and Carol Slater, to stay on at the island as ecological reserve guardians. Since that time the Coastguard has cooperated to keep the equipment updated.

Two new double walled tanks that meet environmental standards were constructed next to the engine room on the island. Fortunately, the need for oil on the island will be reduced in the future when more Sustainable Energy Systems are developed.

Since the Coast Guard lease from the Provincial Environment and Lands Department was changed to reflect the decreasing envelope of use by the Coast Guard, the rest of the Island was then returned to the Province, and plans were made to include that as part of the Ecological Reserve. An agreement was made with Coast Guard and Provincial Environment officials as to what would constitute site remediation for the island.

This image shows the 7 old fuel tanks used for energy. They were single walled tanks and they could have contributed to an oil spill in that sensitive environment. The concrete pool around the cradles was built to contain any leaks or spills

This image shows the 7 old fuel tanks used for energy. They were single walled tanks and they could have contributed to an oil spill in that sensitive environment. The concrete pool around the cradles was built to contain any leaks or spills

In the spring of 2000, they had planned to remove the concrete base for the oil drums as well, but it was considered that it may prove too much of an environmental impact given that the pigeon guillemots, sea gulls and black oystercatchers were establishing nesting territories .They agreed to put it off until a time in the year of minimal impact. It was decided that January and February would be ideal. By May of 2001, the Canadian Coast Guard removed the set of 7 fuel old oil tanks from Great Race Rocks. These tanks had been installed in the 1970’s when the environmental regulations regarding such installations were not as stringent as they are today.

In the spring of 2000, they had planned to remove the concrete base for the oil drums as well, but it was considered that it may prove too much of an environmental impact given that the pigeon guillemots, sea gulls and black oystercatchers were establishing nesting territories .They agreed to put it off until a time in the year of minimal impact. It was decided that January and February would be ideal. By May of 2001, the Canadian Coast Guard removed the set of 7 fuel old oil tanks from Great Race Rocks. These tanks had been installed in the 1970’s when the environmental regulations regarding such installations were not as stringent as they are today.

On January 16, 2001 the coast guard delivered by helicopter the equipment necessary for removal of the concrete tank farm retaining berm.

On January 16, 2001 the coast guard delivered by helicopter the equipment necessary for removal of the concrete tank farm retaining berm.

By mid- February, a large pile of concrete rubble was all that was left of the cradle.

. The concrete had been neatly pealed from the original rocks underneath and it was now ready for the next stage.. Removal by helicopter.

By the end of April 2001, the Coast Guard had completed the removal of all the concrete rubble by helicopter and the outcrop is restored to bare rock again.

We have attempted to keep out invasive plant species and have planted seeds from native grasses in the small crevices of the rock. The seagulls responded to this new extension of territory and within two years took it over as a nest site

We have attempted to keep out invasive plant species and have planted seeds from native grasses in the small crevices of the rock. The seagulls responded to this new extension of territory and within two years took it over as a nest site

These pictures were taken in February, 2005. From the tower, the area which contained the tank farm, is no longer distinguishable.

The rock outcrops have been recolonized by native plants.

We also watch for excessive growth of introduced invasive species, and selectively remove them by hand

First Nations Cooperative Management of Protected Areas in British Columbia, Tools and Foundation

The following excerpt presents the Te’Mexw Treaty Association assertion in response to the proposal for the Race Rocks MPA in 1998. See bolding below:

First Nations Cooperative Management of Protected Areas in British Columbia:

Tools and Foundation

by Julia Gardner Dovetail Consulting April 2001

From page 9:

An ecosystem approach

The designation of special management zones in LRMPs recognizes that protected areas

cannot be managed as islands: buffers and connecting corridors beyond their boundaries

are needed to ensure that ecological integrity is protected. Similarly, marine protected

areas cannot protect marine biodiversity on their own – they should be implemented as a

part of integrated coastal zone management.

The management of protected areas on an ecosystem level is a priority that has been

brought into the public eye recently through the report of the Panel on the Ecological

Integrity of Canada’s National Parks (Parks Canada Agency, 2000) and the report of

B.C.’s Park Legacy Panel (MELP, 1999). There is growing recognition that the

ecosystems of protected areas cannot be protected without attention to the portions of

their ecosystems falling outside their boundaries, as opposed to being “islands in a sea of

development.”

In the marine setting, there is a parallel rationale for an ecosystem approach, often under

the label, “integrated coastal zone management.” But in this “sea of development” where

fluid ecosystems even more thoroughly defy protection via boundaries, some argue that

protected areas are contrary to the priority of protecting the whole environment. For

example, “The Nuu-chah-nulth believe that all marine areas should be treated respectfully

for the gifts that nature provides. The concept of establishing certain areas for favourable protection while mismanagement occurs in areas outside of protected zones is foreign to

Nuu-chah-nulth principles” (Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, November 13, 1998) Similarly, the Te’Mexw Treaty Association asserted in response to the proposal for the

Race Rocks MPA in 1998 that “It is the position of the Nations that a coordinated co-management program for the coast from Jordan River to Ten Mile Point would be the appropriate method by which conservation, harvest and priority for First Nations users can be integrated” (Moahan, 1998,p7). at the very least, MPAs need to be considered in their broader setting, including the watershed and the surrounding sea.

A sixth key assumption is that land and sea are an integrated whole, so MPAs

alone cannot protect the marine environment. Nevertheless, we can usefully

consider the particular circumstances of protected areas in the water, so as to

increase their extent and effectiveness through cooperative management.

Webcast to New York Conference Spring, 2001

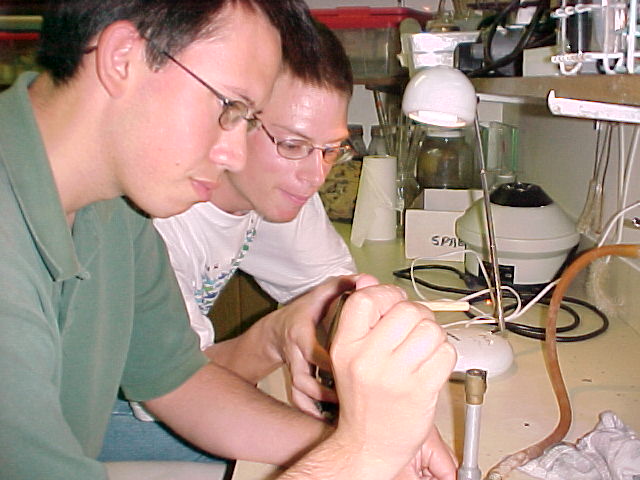

During a presentation to the ETC conference at the United Nations School in New York in the spring of 2001, we tried out the underwater audio link from DIVELINK . An audio signal is relayed by SONAR for Ryan to a receiver near the docks. This receiver was connected to the audio input on the G3 laptop computer and to the shore tender as well. Both voices could be carried by the Sorenson Broadcaster first by wireless AirPort and then onto the internet. In this way we were able to communicate from underwater in the Pacific Ocean live by internet to the Altlantic coast. In this video, Ryan Murphy, a student at Pearson College, operates the device and the camera was operated by Jean-Olivier Dalphond, also a student at the college.

newyork_300.mov

Airport: Wireless Technology at Race Rocks

In April 2001, The APPLE Learning Interchange supplied an AirPort wireless Base Station and three AirPort cards for the iMacs at Race Rocks. Now all cameras could run on Wireless computers at Race Rocks.

We started experimenting by using the AirPort base station for wireless web casting in June of 2000 . This link shows several pictures of the AirPort in use at that time

- We started experimenting with using the AirPort base station for wireless web casting in June of 2000 . Her David from Egypt is at the controls.

- Victor hoisting an airport to the top of the science building

- This time in order to get a better coverage over more of the island while using the mobile camera and computer, we hoisted the Airport up the flagpole .

- In September when our students came back for orientation week, another series of experimental webcasts were done throughout the week.

- Garry, Michael and Jean undertake to attach a new Lucent Wave-LAN extender antennae to the existing AirPort base Station in order to give greater coverage for mobile webcasting on the island.

- This procedure involved taking the AirPort apart, removing the Lucent PCMCIA card and cutting out some plastic of the supporting case with a hot needle in order to fit the small plug into the antenna.

- An operation which of course voids the warranty, but one that if successful will extend the range of our wireless webcasting to 200 meters. This should adequately cover the whole island, and out to the boat when we are diving offshore.

- A successful operation – and now to take it back out to Race Rocks to install it on the roof of the Marine Science Centre building.

- By early October we had done just that. In an inverted plastic gallon jug with an Apple on one side and a Lucent circle on the other, the new antenna inside now gives exceptional coverage of almost the whole MPA, well beyond the 200 meters recommended.

- A wire runs through the roof of the science centre and connects with the AirPort base station in the Attic. This is plugged into the LAN which leads to the Microwave radio for relay to the internet at Pearson College on Vancouver island.

- Garry couldn’t wait to see what range was possible so a quick trip out with Angus in Hyaku proved it was working. From the location shown above, using netscape on the iBook, the remote camera on the island was focused on the boat. At the same time using the G3 PowerBbook, on the boat, transmission of a webcast of the tower and the island was achieved.

- The following day, the racerocks.com crew came out to test out the reception at different locations on the island.

- Webcasting using Sorenson Broadcaster, reception from the boat out near West Race Rocks was as good as that right next to the marine science centre.

Ryan describing what the divers were videoing underwater during a presentation in the QuickTime Live Conference in California. The webcast was done wireless to the AirPort base station in the marine science centre

Anarrhichthys ocellatus: Wolf Eel –The Race Rocks Taxonomy

Anarrhichthys ocellatus

- This Wolf eel has taken up residence somewhere in the vicinity of the tidal current energy piling. August, 2008 photos by Erik Schauff (copyright)

This video shows Pearson College Diver Jason Reid with a wolf eel and was broadcast live in the Underwater Safari Program in October 1992

Description: Although the behaviors of the wolf eel are relatively limited at this moment, they still deem to be one of the most interesting species found in the waters. Its name originates from the greek word Anarhichas-– a fish in which the wolf eel resembles– and the latin word ocellatus which means eye-like spots. In general, Wolf-eels are easily to identify. There name suggests that they resemble eel like structures which range in colour from grey to brown or green. Starting from a young age, their coloration starts with a burnt orange spotted look graduallty changing into a dominant grey for males and brown for females. The males and females both have a dorsal fin that stretches from head to the end of their body. On average, a Wolf-eel is seen to possess a body of 2 meters long and characterized by a unique pattern of spots that appear to be individualized both in males and in females. In addition, the Wolf-eel possesses a large square head coupled with powerful jaws and canine teeth allowing for easier mastication– a beneficial adaptation to its environment of hard-shelled animals.

Classification:

Domain Eukarya

Kingdom Animalia

Phylum Chordata

Class Actinopterygii

SuperOrder Acanthoptergygii

Order Perciformes

SubOrder Zoarcoide

Family Anarhichadidae

Genus Anarrhichthys

Species ocellatus

Common Name: Wolf-eel

Habitat and Range: Wolf-eels can most abundantly be found from the sea of Japan and the Aleutian islands continuing southwards to imperial beach, Southern California. Wolf-eels live from barely subtidal waters to 740 feet (Love, 1996). The island of Racerocks is one of the sites in the Pacific Northwest in which the Wolf-eel can be found. Exploring the island, the most common places would be near the Rosedale reef and along the cliff near the docks. The rocky reefs and stony bottom shelves at shallow and moderate depths serve to be the abodes of the Wolf-eel. They will usually stake out a territory in a crevice, den or lair in the rocks. In addition, the Wolf-eel possesses a long, slender body which allows them to squeeze into their rocky homes. During the juveniles years of the Wolf-eel, they can most commonly be found in the upper part of the water, residing there for about two years. As the Wolf-eel ages, it will slowly migrate to the ocean floor and maintain an active lifestyle. Eventually, the Wolf-eel will find a rock shelter and “vegetate” for the remainder of its lifespan.

Diet: The adaptation of the Wolf-eel’s jaw to crush hard objects, as mentioned, deems to be beneficial for eating other organisms around its environment. The gourment delicacies that the Wolf-eel feeds upon are crustaceans, sea urchins, mussels, clams, snails some other fishes.

Mating and Other Interesting Facts: In aquaria, males and females form pairs at about 4 years of age and produce eggs at 7 years old. Spawning usually occurs from October into late winter. A male will butt his head against the female’s abdomen then wrap himself around her as a sign for a mating call. It has been found that the male fertilizes the eggs as they are laid and up to 10 000 eggs can be released at a single time. The father and mother will then wrap themselves around the egg masses and will guard the eggs for about 13-16 weeks when the eggs will then hatch. Possible predators that prey on the eggs include Benthic rockfishes and kelp greenlings. This process will continue periodically and repetitively for the lifespan of a Wolf-eel as it has been found that Wolf-eel’s mate for life.

Conservation Notes: At the moment, many fishers use rockhopper trawls to fish rough, rocky sea floors. This method causes the destruction of the rocky reefs in which the Wolf-eel resides. At the current moment, scientists are calling for a halt in the use of rockhopper trawls and an alternative method of using longline traps which don’t harm the rocky reefs.

References: Love, Milton, Probably more than you want to know about the fishes of the Pacific Coast: A humorous guide to Pacific fishes, California, Really Big Press, 1996, pg. 298

Lamb, Andy and Edgell, Phil, Coastal Fishes of the Pacific Northwest, BC Canada, Harbour Publishing, 1986, pg. 94.

Other members of the Class Actinopterygii at Race Rocks.

and Image File |

The Race Rocks taxonomy is a collaborative venture originally started with the Biology and Environmental Systems students of Lester Pearson College UWC. It now also has contributions added by Faculty, Staff, Volunteers and Observers on the remote control webcams. The Race Rocks taxonomy is a collaborative venture originally started with the Biology and Environmental Systems students of Lester Pearson College UWC. It now also has contributions added by Faculty, Staff, Volunteers and Observers on the remote control webcams.Dec. 2001 Zaheer Kanji, (PC) Edmonton Alberta |

Financial Proposal For Race Rocks Operation

The following operational budget provided details of projected minimum operational expenses at Race Rocks for the period April 1, 2001 to March 31, 2002. The budget is based on our four years of experience in funding the Race Rocks project and the highly efficient operational format we have established. Pearson College guarantees to cover any cost over runs if they should occur.

It is proposed that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, BC Parks, and Pearson College each contribute $50,000 to cover the 2001-2002 operating budget.

(Ed Note: As of 2012 Neither Provincial or Federal governments have responded to this request with any financial support. During that time Pearson College has raised funding separate from the college funding to maintain operations at Race Rock.)

|

Race Rocks MPA/ER

|

|

|

Operating Budget April 1, 2001 to March 31, 2002

|

|

|

Salaries

|

|

|

Eco-guardian(s)

|

42,000

|

|

Educator (1/2 time)

|

30,000

|

|

Shore-side support (1/3 time)

|

14,000

|

|

Benefits

|

9,460

|

|

95,460

|

|

|

Fuel

|

|

|

Generator

|

11,000

|

|

Heating

|

1,400

|

|

Boat

|

1,750

|

|

Lube/oils

|

2,000

|

|

16,150

|

|

|

Maintenance

|

|

|

Buildings

|

6,000

|

|

Generators

|

4,300

|

|

Water pumps

|

2,100

|

|

Desalinator

|

2,200

|

|

Winches

|

800

|

|

Boat and motor

|

4,700

|

|

Jetty

|

400

|

|

Fuel system

|

450

|

|

Radios

|

200

|

|

Diving equipment

|

2,500

|

|

23,650

|

|

|

Administration Costs

|

|

|

Phone

|

600

|

|

Insurance

|

1,800

|

|

Stationery/printing

|

1,150

|

|

3,550

|

|

|

Education Program

|

|

|

Classroom materials

|

4,500

|

|

Communication/outreach programs

|

2,500

|

|

First Nations’ program

|

5,000

|

|

Internet access

|

2,000

|

|

14,000

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total expenditures

|

$152,810

|

Testing the Divelink audio system Underwater at Race Rocks

Jean-Olivier Dalphond and Garry Fletcher listen to the diver Ryan Murphy, (PC Year 26) as he tests out the DIVELINK system from underwater at Race Rocks. We were able to add this underwater sound ( which is carried by sonar – up to 50 meters underwater) to live webcasts by the end of the term in April 2001.