FROM: https://mpanews.openchannels.org/news/mpa-news/using-multibeam-sonar-map-mpas-tool-future-planning-and-management

FROM: https://mpanews.openchannels.org/news/mpa-news/using-multibeam-sonar-map-mpas-tool-future-planning-and-management

Using Multibeam Sonar to Map MPAs: Tool of the Future for Planning and Management?

The seafloor – sandy or rocky; flat or sloped; seamount or canyon – provides the foundation for multiple processes within MPAs, including the distribution of flora and fauna. However, MPA practitioners have generally had only patchy knowledge, at best, of what lies at the bottom of their protected sites, based on information gathered from fishermen, divers, and rough bathymetric data from nautical charts. With an inexact understanding of what’s “down there”, planners and managers face a real challenge of drawing appropriate boundaries and protecting the habitats they want to protect.

Under such conditions, multibeam sonar may be the tool of the future for MPA practitioners. Used now at a small number of MPAs in North America, this mapping technology provides resource managers with the ability to envision the seabed as they never have before. Practitioners are using it to pinpoint boundaries, streamline research costs, identify and reduce ecosystem impacts from fishing, and more. This month, MPA News examines the technology of multibeam sonar and how resource managers are adapting it to fit their needs.

The basics of multibeam sonar

Maps of the seafloor made over the past century vary widely in accuracy. Older navigation systems resulted in features being mapped several hundred meters or even kilometers from their actual geographic locations. Systems to measure depth resulted in errors of tens to hundreds of meters. Depending on the spatial resolution of the mapping system, objects less than a certain size – even undersea mountains, in some cases – could fail to appear at all.

US military researchers developed multibeam sonar in the 1960s to address these problems. Mounted on a ship’s hull, the sonar sends a fan of sound energy toward the seafloor, then records the reflected sound through a set of narrow receivers aimed at different angles. Declassified for civilian use in the 1980s, the technology has since advanced to the point where it can detect features as small as one meter across and locate them to within one meter of their true geographic location. It provides users with two kinds of data: bathymetric (depth) data, and “acoustic backscatter”. The latter, which records the amount of sound returned off the ocean bottom, helps scientists identify the geologic makeup – sand, gravel, mud – of the seafloor.

In the 1990s, government hydrographic agencies appropriated the technology to improve the accuracy of their nautical charts, particularly in harbors subject to sediment shifting and other navigation obstacles. Oil and gas companies seized on multibeam sonar to help explore the seabed in their search for hydrocarbon deposits. And by the late 1990s, some MPA managers began to see the possibilities offered by the technology for studying seafloor habitats. Jim Gardner, a marine geologist with the US Geological Survey, said, “Multibeam sonar gives managers, for the first time, a very clear view of the bathymetry and backscatter of their MPA – it’s really the first time they’ve seen what they’re protecting.”

One question that the technology helps practitioners to answer is, Where should an MPA be sited? “A lot of people just draw a polygon on a map, and that becomes their marine protected area,” said John Hughes Clarke, a marine geologist at the University of New Brunswick, Canada. But drawing an arbitrary line fails to consider the hydrographic forces – such as currents – that affect a site, or its topography. Notably, the Canadian government has expressed interest in using multibeam sonar to help it redraw the boundary for its exclusive economic zone, which officials aim to extend beyond the current 200-nm range in areas where the continental shelf stretches beyond that line.

Hughes Clarke believes that Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) should take account of the seabed whenever designating MPAs. His team of researchers is mapping the Musquash Estuary, a shallow, partly intertidal area in New Brunswick that DFO is considering for formal MPA designation. In the estuary, he is using a series of multibeam surveys to map erosion, sediment deposition, and other surface-sediment changes over time – factors to consider when drawing up a management plan for the site.

Robert Rangeley, marine program director for the Atlantic regional office of World Wildlife Fund Canada (an NGO), said multibeam sonar benefits seafloor conservation in a number of ways. “First, the better we know the distribution of bottom types, the better we can map out both distinctive and representative habitats for protection,” he said. “Second, we can better understand the relationships between patterns in benthic habitats and patterns in the distributions of benthic organisms. And third, by limiting bottomfishing to those areas with high fisheries yield, the area of seafloor that is impacted by bottom gear – and the diversity and abundance of bycatch – can be reduced.”

Use of multibeam in marine protected areas

The number of marine protected areas that have been mapped using multibeam sonar is very small. The technology remains unfamiliar to many practitioners, and the cost to deploy it can be fairly high (see box Questions and answers on multibeam sonar). Nonetheless, planners and managers of several sites have incorporated it in their work, illustrating a mix of potential applications:

————-

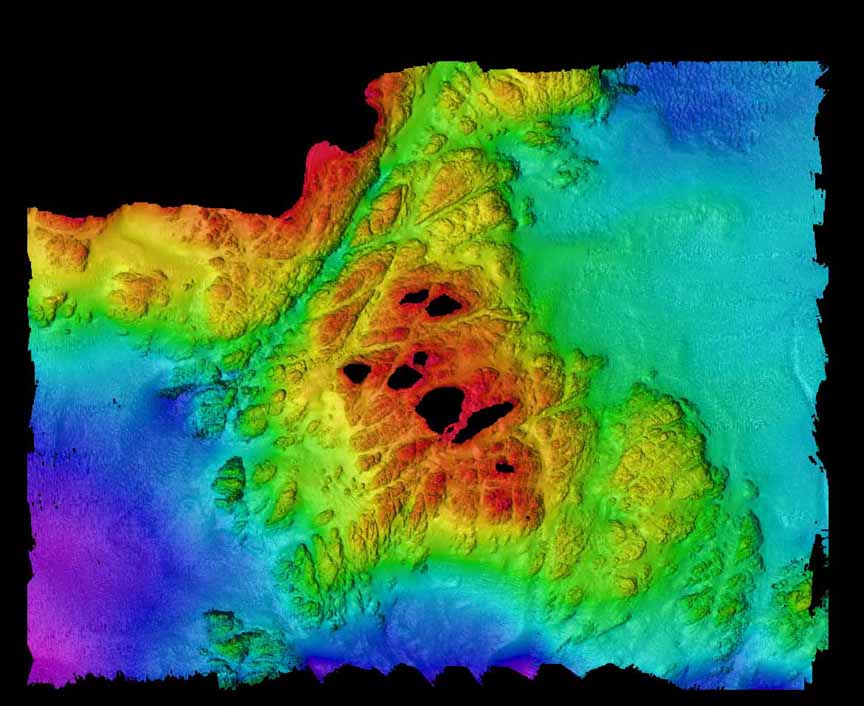

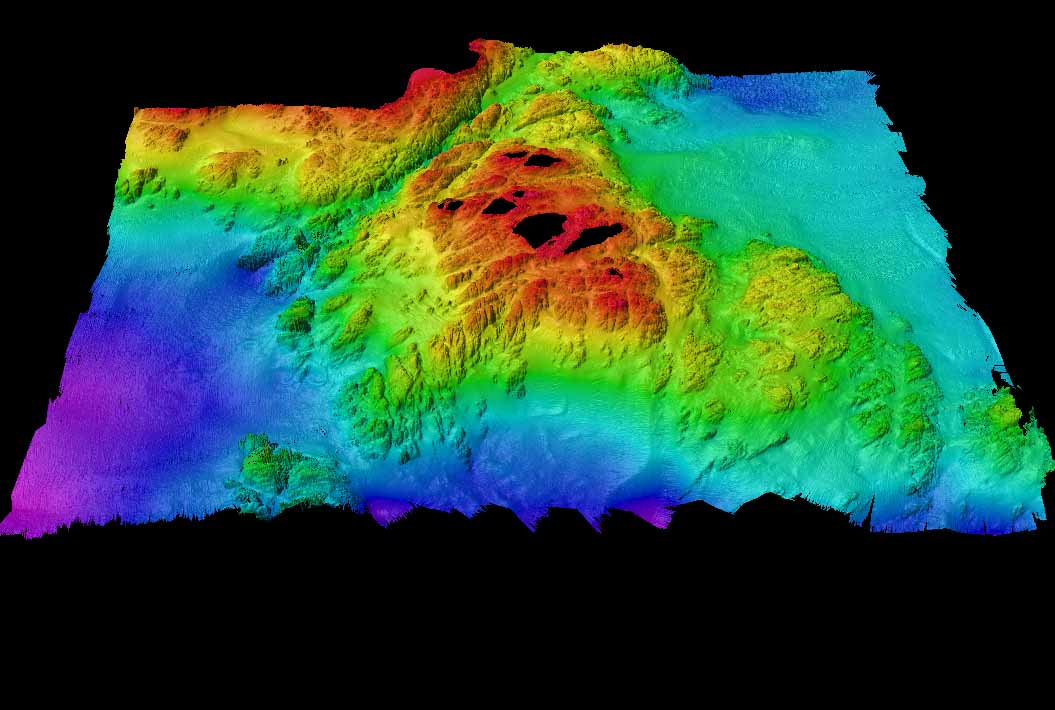

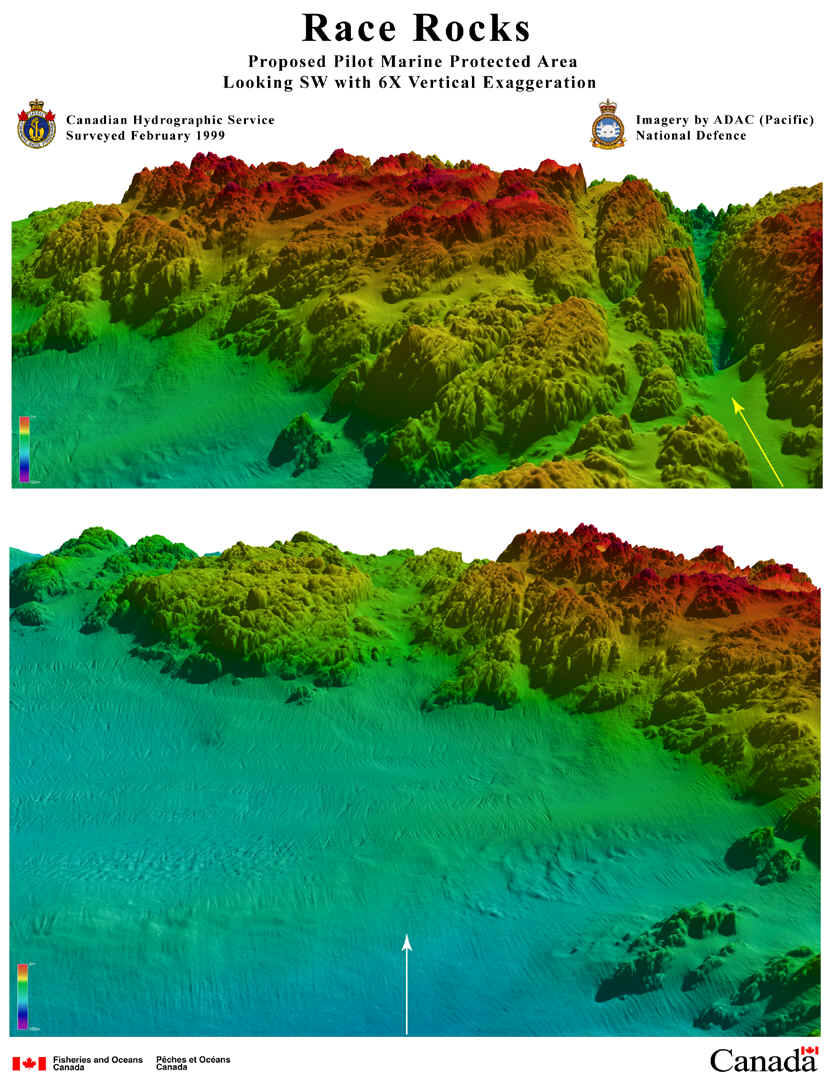

Race Rocks Area of Interest, Canada

The rugged Race Rocks archipelago off the province of British Columbia is on the verge of formal, federal designation as a marine protected area. Researchers have conducted a series of seabed surveys of the site – with multibeam sonar and other technologies – resulting in detailed imagery of rock outcrops, small sand waves, sediments located in depressions in rocky zones, and more. “The definition of the seabed assists in estimating the degree of uniqueness of this area, a fundamental requirement for designation as an MPA,” said Jim Galloway, head of sonar systems for the Canadian Hydrographic Service. “Similarly these baseline surveys contribute to our knowledge of nursery locations within the boundary, thereby giving us the means to protect species and habitat appropriately.” As it has done for Flower Garden Banks, the multibeam mapping has also contributed to community education efforts. “The dramatic imagery and definition greatly assisted stakeholders in their appreciation of the suitability of Race Rocks to be assigned MPA status,” said Galloway. Incidentally, the Canadian Hydrographic Service is located within the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, which is responsible for designating MPAs in Canada. This co-location of responsibilities helped ease the process of executing the seabed surveys at Race Rocks and reduced operational costs, said Galloway.

For more information:

Jim Gardner, US Geological Survey MS-999, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, CA 94025, USA. Tel: +1 650 329 5469; E-mail: jvgardner@usgs.gov.

John Hughes Clarke, Ocean Mapping Group, Department of Geodesy and Geomatics Engineering, University of New Brunswick, P.O. Box 4400, Fredericton, NB E3B 5A3, Canada. Tel: +1 506 453 4568; E-mail: jhc@omg.unb.ca.

Leslie Burke, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Regional Director’s Office, Scotia-Fundy Fisheries, P.O. Box 1035, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia B2Y 4T3, Canada. Tel: +1 902 426 9962; E-mail: burkel@mar.dfo-mpo.gc.ca

Andrew David, National Marine Fisheries Service, 3500 Delwood Beach Road, Panama City, FL 32408, USA. Tel: +1 850 234 6541 x208; E-mail: andy.david@noaa.gov.

G.P. Schmahl, Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, 216 W. 26th Street, Suite 104, Bryan, TX 77803, USA. Tel: +1 979 779 2705; E-mail: george.schmahl@noaa.gov.

Jim Galloway, Canadian Hydrographic service, Institute of Ocean Sciences, 9860 West Saanich Road, Sidney, BC V8L 4B2, Canada. Tel: +1 250 363 6316; E-mail: gallowayj@pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca.