TEMPERATURE: Max 6.1C — Min 3.3C — Reset 4.9C — Rain 0.8 mm

HUMAN INTERACTION: Two groups of students came over in 2nd Nature this afternoon to learn the intricacies of the desalination plant that provides our fresh water. Two tour boats were in the reserve at 14:40 one of which did approach Middle Rock a little too close and caused some Sea Lions to take to the water. I think actually having people standing so high on an observation deck was very threatening to the animals. Garry happened to be in the tower so obtained this video of the disturbance:

http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/archives/videcotourimpact.htm

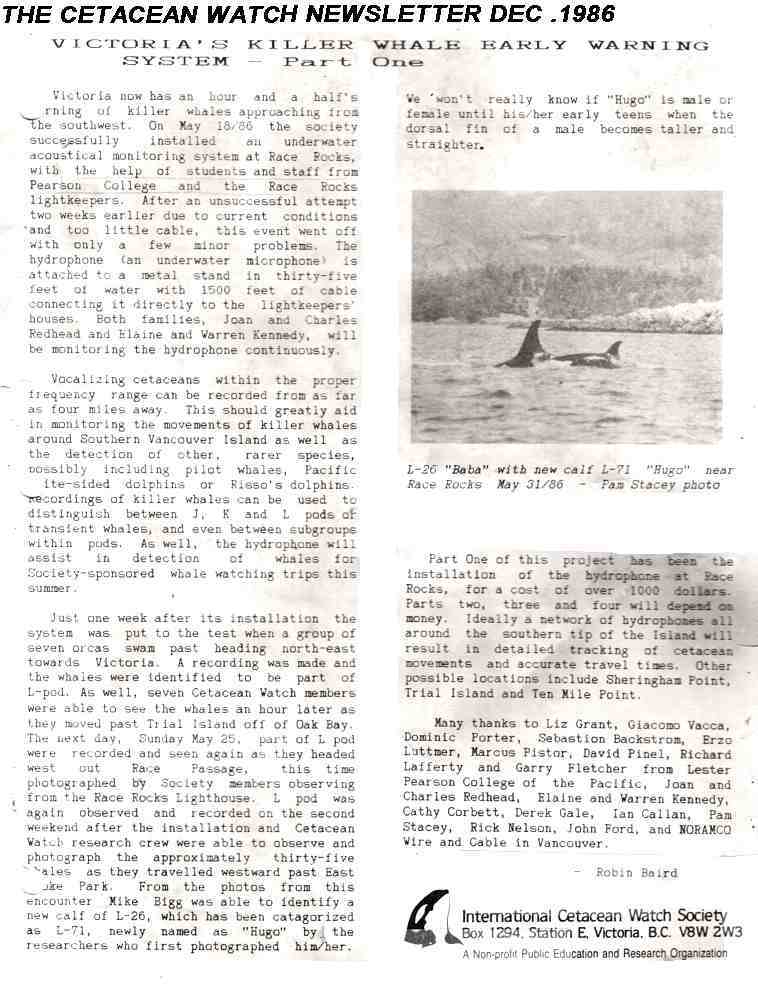

Sadly we have a dead marine mammal at the base of the ridge along the east shore of Great Race. Even with the telescope I cannot tell whether it is a Harbour Seal,an Elephant Seal or a California Sea lion and I can’t get close enough without disturbing the 50 or so Sea Lions and 2 Elephant Seals hauled out all around to make a positive ID.MARINE LIFE: At approximately 16:00 we saw 6 or 7 Orca just east of North Rocks, unfortunately it was too dark for filming but what a sight! There was one very large bull in the group and one quite small Orca, possibly a calf. They were breaching and slapping their tails and really churning up the sea. They started out in fairly large circles diving, porpoising and rolling and the large bull breaching quite often. After about 10 minutes the circles got smaller and they started swimming very fast on their sides with their dorsals at about a 45 degree angle to the water. They were quite low in the water and were sort of ‘plowing’ the water,back and forth,around and around.Finally with the telescope we did see the reason for all the activity, one unlucky California Sea Lion. Twice the Sea Lion was tossed in the air. We watched until it was too dark to see anything except a few white splashes. As all this was going on there was a group of 30-40 sea gulls circling over-head ready to snatch up any ‘crumbs’ that might come their way -nothing is wasted in this example of the food chain.

posted by Carol or Mike S at 6:08 PM