This spreadsheet was made by Garry Fletcher as part of the Race Rocks ecological overview done for DFO . The links have not been updated since the website had to be moved from the Telus Server. The references are also housed in the bookshelf in the Marine biology lab at Pearson College. This alternate link here may be preferable here also: Most references should also be available in a google search.

| References ID | Reference Type | Author1, Author2, Author3 | year | Title | Journal, report, book title | editor | Volume | Number | page | URL | Call Number | Abstract | Comments | Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Refereed Journal | Brinckmann-Voss – Anita | 1996 | Seasonality of Hydroids (Hydrozoa, Cnidaria) from an intertidal pool and adjacent subtidal habitats at Race Rocks, off Vancouver Island, Canada | Scientia Marina | . | 60 | 1 | 89-97 | rrrefer/Anita’s/seasonal.htm | 593.55 Bri S | None available– See Comments or Links | Includes useful section on systematics, line maps of the Race Rocks Area, and species lists of hydroids from specific tidepools and subtidal areas. Complete text and diagrams included in link. | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/hydroid/pub/seasonal.htm |

| 3 | Refereed Journal | Brinckmann-Voss- Anita,Lickey-D.M.,Mills-C.E. | 1993 | Rhysia fletcheri (Cnidaria, hydrozoa, Rhysiidae), a new species of colonial hydroid from Vancouver Island ( British Columbia, Canada) and the San Juan Archipelago ( Washington, U.S.A.) | Can.Journal of Zool. | . | 71: | 2 | 401-406 | Rhysia/Rhysia.htm | 593.55 Bri | A new species of colonial athecate hydroid, Rhysia fletcheri , is described from Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, and from Friday Harbour, Washington, U.S.A. It’s relationship to Rhysia autumnalis Brinckmann from the Mediterranean and Rhysia halecii (Hickson and Gravely) from the Antarctic and Japan is discussed. Rhysia fletcheri differs from Rhysia autumnalis and Rhysia halecii in the gastrozooid having distinctive cnidocyst clusters on its hypostome and few, thick tentacles. Most of its female gonozooids have no tentacles. Colonies of R. fletcheri are without dactylozooids. The majority of R. fletcheri colonies are found growing on large barnacles or among the hydrorhiza of large thecate hydrozoans. Rhysia fletcheri occurs in relatively sheltered waters of the San Juan Islands and on the exposed coast of Southern Vancouver Island. | Microphotographs of male and female specimens and Systematics discussion are included with the description of this new species found at Race Rocks. Color photographs by the author of male and female specimens are included in the link to the article. We wish to acknowledge the National Research Council of Canada who have kindly consented to the printing of this article. We also wish to thank the author, Dr. Anita Brinckmann-Voss for providing the color photographs of the specimens for the web site | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/hydroid/anitabv.htm |

| 4 | Refereed Journal | Ford, John K.B. | 1991 | Vocal Traditions among resident killer whales(Orcinus orca) in coastal waters of British Columbia | . | . | 69 | . | 1454-1481 | . | . | Underwater vocalizations were recorded during repeated encounters with 16 pods, or stable kin groups, of killer whales (Orcinus orca) off the West Coast of British Columbia. Pods were identified from unique natural markings on individuals. Vocal exchanges within pods were dominated by repetitious discrete calls. Pods each produced 7-11 (mean 10.7) types of discrete calls. Individuals appear to acquire their pod’s call repertoire by learning, and repertoires can persist with little change for over 25 years. Call repertoires differed significantly among pods in the resident population. The 16 pods formed four distinct acoustic associations, or clans, each having a unique repertoire of discrete calls or vocal tradition. Pods within a clan shared several call types but no sharing took place among clans. Shared calls often contained structural variations specific to each pod or group of pods within the clan. These variants and other differences in acoustic behavior formed a system of related pod-specific dialects within the vocal tradition of each clan. Pods from different clans often traveled together, but observed patterns of social associations were often independent of acoustic relationships. It is proposed that each clan comprises related pods that have descended from a common ancestral group. New pods formed from this ancestral group through growth and matrilineal division of the lineage. The formation of new pods was accompanied by divergence of the call repertoire of the founding group. Such divergence resulted from the accumulation of errors in call learning across generations, call innovation , and call extinction. Pod-specific repertoires probably serve to enhance the efficiency of vocal communication within the group and act as behavioural indicators of pod affiliation. The striking differences among the vocal traditions of different clans suggest that each is an independent matriline. | . | . |

| Walker- Bruce | 1987 | Pearson College Transect Data – Methods. | . | . | . | . | 9 | . | . | None available– See Comments or Links | Report on how to set up a transect and use transect data with reference to Race Rocks. | . | ||

| Helm – Denise | 1996 | Light station Falls into College Hands | Times- Colonist | . | Dec 12 | . | . | . | 577.7 Hel Ra | None available– See Comments or Links | . | . | ||

| , | Veiogo-Peniasi S. | 1991 | A study of the level of Parasitic Infection (in crabs) between two separate locations. | . | . | . | . | 30 | . | 578.65 Vei | Two locations were chosen to try to determine, and compare the level of parasitic infection between them. From each location, a total of forty crabs were observed for two species of parasites, and the test showed that there was, indeed, a difference in the level of parasitic infection between the two locations. I have purposely chosen in this study a few factors that could possibly be responsible for the observation stated above. In doing so, I picked factors that were most closely associated with the crabs and their natural habitats. Neither the sex nor the size of the crabs affects the level of infection in both the locations (i. e. there is no linear relationship between the level of infection and the size or sex of the crabs); the parasites infect all crabs with almost the same frequency showing no preference to any particular sex or size. Therefore, this is a very simple and straightforward study with the prime objective of solving an ecological problem, basing much of the conclusions on preliminary observations. Furthermore, this study tries to stimulate and encourage wider and more extensive research of marine parasites and their role in the ecology of marine life. |

Study to compare the level of parasitic infection between two different locations – Pedder Bay and Race Rocks. 40 crabs were observed for two parasites to observe if a relationship existed between the level of infection and the size of the hosts, as well as its sex. | . | |

| Odeh- Omar | 1991 | Microorganism association withHalosaccion glandiforme. | . | . | . | . | 36 | . | . | This study involves the microorganisms associated with Halosaccion glandiforme. The samples of Halosaccion glandiforme were taken from Race Rocks Island in the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve.In this study the main purpose was to detect the effect of certain characteristics of the habitat (Halosaccion glandiforme) on the diversity and population of the species present inside Halosaccion glandiforme. The results of this study show that the diversity and population of the species present in Halosaccion glandiforme is sometimes affected by the factors studied. The factors that were studied include total surface area of the sample, the location of the species within Halosaccion glandiforme and the fact that some samples have their top part open and others closed. | Study done in the Race Rocks ecological reserve to detect the effect of certain characteristics of the red algae habitat (H. glandiforme) on the diversity and population of the species present inside H. glandiforme. | . | ||

| Obee-Bruce | 1986 | Race Rocks | Beautiful British Columbia | . | . | . | . | rrrefer/obee/obee.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | Article about Race Rocks, off southern Vancouver Island. | . | ||

| Hardie-D.,Mondor-C | 1976 | Race Rocks National Marine Park- A Preliminary Proposal | . | . | . | . | 69 | rrrefer/rrnatpark.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | The federal- Provincial task force Working Group established in 1972 selected the marine and coastal area surrounding Race Rocks as one of several sites in the Strait of Georgia and Juan de Fuca Strait warranting further study as a potential marine park. In 1973 a second task force was given the responsibility of developing a proposal for establishing the same. Complete copy in this database. | . | ||

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 1998 | Marine Protected Areas Program Policy | . | . | . | . | 27 | http://www.oceansconservation.com | 577.7 Mar C | None available– See Comments or Links The Marine Protected Areas Program Policy provides the rationale for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ efforts with respect to the identification, development, establishment and management of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) under the Oceans Act. |

The purpose of this document was to give the public an opportunity to review and comment upon the elements of the Marine Protected Areas Program. | . | ||

| Hagler- Bailly Consulting, DavidF.Dickens Associates,Robert Allan Ltd. | 1995 | Benefit-Cost Analysis of Establishing a Dedicated Rescue/Salvage Tug to Serve Canada’s Southern West Coast | . | . | . | . | 92 | . | . | This report provides a benefit-cost analysis for establishing one dedicated rescue/salvage tug near the entrance to Juan de Fuca Strait on the west coast of Canada. The primary role of the tug would be to rescue a disabled oil tanker or major vessel. The tugs area of operation is assumed to be a 78 nautical-mile radius from Bamfield, British Columbia, which is located along the southern portion of Barkley Sound. This area encompasses a wide portion of Pacific Rim National Park and extends as far southeast as Port Angeles and as far north as Clayoquot Sound. These areas contain physical, biological, and recreational resources that are at risk from oil spills, and that have been injured by oil spills in the recent past. |

Comments on Juan de Fuca Wildlife Impacts of Oil Spill Chapter 5 ” Benefits from establishing The rescue/Salvager Tugboat Program” is useful: Figures C1-C3 show oil spill paths in Strait of Juan de Fuca |

. | ||

| Anderson- David | 1989 | Report to the Premier On Oil Transportation and Spills | . | . | . | . | 110 plus 25 pages in appendix | . | 363.7394 And | This report is based on four month’s of public hearings in the coastal communities of British Columbia during the summer of 1989. The diverse proposals and recommendations coming from the public have been grouped, assessed, and where necessary supplemented, in order to come up with a coordinated and comprehensive series of recommendations to reduce marine oil spill risks and to improve response capability. The document is not focused on areas of provincial jurisdiction: the nature of the problems faced in oil spill prevention and response, the presentations of the public, and the approach of the Premier all suggest that the subject be considered as a whole. |

. | . | ||

| Water Management Services | 1971 | The Environmental Consequences of The Proposed Oil Transport Between Valdez and Cherry Point Refinery | . | . | . | . | . | . | 363.7382 Env | The hazard to the marine and coastal environments associated with tanker transport may be considered to occur in two related, but distinct, ways. One is the continuing leak of oil to the environment resulting from the myriad of routine operations associated with the oil industry, both intentional and accidental, which contributes the major but less spectacular contribution to marine oil pollution. The other is the spill arising from mishap (grounding, collision, structural failure or fire) in which all or a significant fraction of the cargo is released to the environment over a short period. |

. | . | ||

| Rosso- Giovanni E. | 1999 | Patterns of Color Polymorphism in the Intertidal Snail, Littorina sitkana at the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area | . | . | . | . | . | rreoref/polymor/giovee.htm | 594.3 Ros | As most intertidal gastropods, the Littorina sitkana shows remarkable variation in shell color. This occurs in both microhabitats that are exposed or sheltered from wave action. There appeared to be a close link between the shell coloration of the periwinkle and the color of the background surface. Fieldwork was carried out at the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area in order to investigate patterns of color polymorphism. Evidence from previous studies was also taken into account to better support interpretations and understand certain behaviors. The results showed that in the study site there was a very strong relation between the color of the shells and the color of the rocks. Light colored shells lived on light shaded rocks and vice versa. An interesting pattern was noticed on the white morphs. These were rare along the coast (Only 2%), but were present in relatively high numbers in tidepools set in white quartz. From previous experience (Ron J. Etter, 1988), these morphs seem to have developed, as an evolutionary response, a higher resistance to physiological stress from drastic temperature changes between tides. Some results showed that the white morph is present in an unexpectedly high percentage at the juvenile stage, but then their number decreases dramatically with age. As in Etter’s study, more research needs to be done on the role of visual predators in this phenomenon. |

This image shows both Black and white color variants of the Littorina sp. Here they are placed against the white quartz background in the shallow water of tidepool #4 | . | ||

| Goddard- James, M. | 1975 | The Intertidal and Subtidal Macroflora and Macrofauna in the proposed Juan de Fuca National Marine Park near Victoria, B.C. | . | . | . | . | 59 pages | rreoref2/jdfmarpk/juanmarpark.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | “Sites Investigated: The sites investigated in this survey were selected as representative of the rocky shore extending from Albert head to Beechy Head. —further effort in the description of the subtidal biota was directed to the unique areas within the proposed park—Race Rocks with the high velocity currents– Species identifications were established using keys and the reference collections of Dobrocky SEATECH Limited, the University of Victoria and the B.C. Provincial museum. Species List For Race Rocks is included in Appendix 8, page 78. Schematic Profile, page 47. RR Description page 45-48. | . | ||

| Ashuvud -Johan , Fletcher -Garry L. | 1980 | Race Rocks Reserve Established | Diver Magazine | . | September | . | 2 | . | 577.7 Rac R | None available– See Comments or Links | This is the first publication of notice to the Diving Community that the Ecological reserve had been established | . | ||

| Sylvestre- Jean-Pierre | 1999 | Canada, les gardiens de Race Rock | Cols Bleus marine et arsenaux | . | 2473 13/02/99 | 6 | . | . | . | None available– See Comments or Links | “Au large de Victoria, au sud del’ile de vancouver, un recif supporte le phare canadien le plus meridional. Ce recif est devenu le gite de quelques milliers d’oiseaux marins du Pacifique et de quatre especes de mammiliferes marins. Les gardiens du phare, Carol et mike Slater, veillent jalousement sur cette reserve ecologique, veritable petit paradis terrestre. “ | . | ||

| Ruckthum- Vorapot | 1981 | The Current Meter at Race Rocks | . | . | . | . | 39 | . | . | None available– See Comments or Links | A description of the events surrounding the installation of the current meter in 1981 that lead to the creation of the Race Passage Current tables | . | ||

| Olesiuk-Peter F., Bigg-Michael A. | 1988 | Seals and Sea Lions on the British Columbia Coast | . | . | DFO/4104 | . | 12 | rreoref/mmammals/sealsandsealions.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | The complete pamphlet with color photos is scanned in at the reference linked here. This pamphlet provided the most recent scientific information on the status of seals and sea lion in B.C up to its publication. It describes general biology, and refers to the conflicts that arise with commercial and sports fisheries. Excellent color photographs of all 5 species. Graphs on Trends of Abundance of harbour seals in B.C.(p3), and Diet of sea Lions Wintering off Southern Vancouver Island (p10) are particularly useful. Some research for this document was obtained by scat samples at Race Rocks ( personal communication with P. Olesiuk) | . | ||

| Anderson-Flo | 1998 | Race Rocks – July 28, 1966-March 2, 1982- | Lighthouse Chronicles Twenty years on the B.C. Lights | . | . | . | 130-218 | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/history/rrkeeper/litchron.htm | 387.155 And | None available– See Comments or Links | The best published account available to date on the life on the light station at Race Rocks. Reference is made to the role of Pearson College in creating the Ecological reserve, page 183-184.( with Photograph) | . | ||

| Webster – I, Farmer,D.M. | 1977 | Analysis of Lighthouse Station Temperature and Salinity Data- Phase II | . | . | . | . | 93 | . | . | This report summarizes certain features of salinity and temperature time series obtained from lighthouse stations along the B.C. coast together with related rainfall data. The presentation is intended to facilitate analysis of temperature or salinity trends and fluctuations as well as the relationships between data from different stations. The data are presented as annual trends, monthly means, standard deviations and spectra cross-spectra. The analysis indicates relatively close correspondence between stations at periods greater than a year, but with significant differences at higher frequencies. | Graphs relating temperature, salinity and rainfall at Race Rocks compared to other stations are shown on the following pages 29,33,45,53,63,65,69,71,75,83,87, and 91 | . | ||

| Matthews-Angus | 1999 | Community Involvement in Marine Protected Areas- Pearson College Communications with Federal Government Levels 1994-1999 | . | . | . | . | ————- | . | 577.7 Com I | This series of documents presents the efforts of Angus Matthews, administrator of Lester B. Pearson College, to offer to the federal government a model of Community participation in creating a marine education center at Race Rocks. It begins with initiation of the proposal in order to provide for a continued presence of personnel at the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve, when the destaffing of the light station is looming on the horizon. The communications between Mr. Matthews and officials of the Canadian Coast Guard, and with the office of the Minister of Fisheries are represented in chronological order. This is the second of two records of communications, document #26 representing the Communications at the Provincial Parks Level. that were going on simultaneously. | This series of documents presents an excellent chronological account of the frustrated efforts of an organization in the community to facilitate a constructive solution to the destaffing of light stations and the simultaneous provision of on sight protection for a sensitive ecological area. | . | ||

| Matthews-Angus | 1999 | Community Involvement in Marine Protected Areas- Pearson College Communications with Provincial Government 1994-1999 with Provincial Levels of government | . | .. | … | . | ————— | . | 577.7.Com | This series of documents presents the efforts of Angus Matthews, administrator of Lester B. Pearson College, to offer to the federal government a model of Community participation in creating a marine education center at Race Rocks. It begins with initiation of the proposal in order to provide for a continued presence of personnel at the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve, when the destaffing of the light station is looming on the horizon. The communications between Mr. Matthews and officials of the Provincial Parks Department are represented in chronological order. This is the second of two records of communications, (document #25 representing the Communications at the Federal Fisheries and Oceans Department,) that were going on simultaneously during a 5 year period. 1994-1999. Government of British Columbia June 20, 1994 Pearson College writes to The Hon. Moe Sihota, Minister of the Environment and Esquimalt – Metchosin MLA to request support for BC Parks involvement in an initiative to operate surplus facilities at Race Rocks as a marine education Centre. June 29, 1994 Minister Sihota writes and expresses interest in the project. Dec. 21, 1995 The Hon. Glen Clark, Minister of Employment and Investment writes to Federal Fisheries Minister Brian Tobin and request a delay in de-staffing light stations. July 8, 1996 Newly appointed Environment Minister The Hon. Paul Ramsey writes to express interest in the plans for Race Rocks and to advise that a management plan is required before his Ministry can proceed. He expects the plan to take one year to be written. July 25, 1996 Pearson College proposes fast tracking the management plan. Sept. 20, 1996 The Ministry of Employment and Investment commissions a report to look into the potential of commercial uses for Race Rocks. Oct. 11, 1996 Minister Ramsey writes to advise that the Province is considering a coast wide plan to operate light stations. Any decision on Race Rocks would wait for this review. Oct. 29, 1996 Pearson College writes to BC Parks, District Manager, Mr. Dave Chater regarding the imminent closure of Race Rocks station, the need for rapid progress on the management plan and advises that the College will pursue Federal Marine Protected Area status for the Reserve. Oct. 31, 1996 Mr. Denis O’Gorman, Assistant Deputy Minister of Parks writes to Mr. Rick Bryant, at Coast Guard, to advise that BC Parks did not have a use for surplus buildings at Race Rocks under the current management plan. A new plan would review this and it would be finished in early 1977. Jan. 30, 1997 Newly appointed Minister of the Environment The Hon. Cathy McGregor writes to confirm the target date for completion of the management plan as early 1997. Feb. 12, 1997 Assistant Deputy Minister O’Gorman writes to advise that BC Parks would support Pearson College’s application for a Crown lease on Race Rocks. Mar. 1, 1997 Pearson College takes over staffing Race Rocks under a temporary two year agreement with the Coast Guard. April 11, 1997 Pearson College applies to BC Lands for a 30 year Crown lease for Race Rocks. Dec. 19, 1997 Mr. Dave Chater writes that BC Parks is prepared to enter into an agreement in principle with Coast Guard. The draft management plan, which is still incomplete, is being amended. April 14, 1998 Mr. Chris Kissinger, Resource Officer at BC Parks writes to Mr. Fred Stepchuk, Superintendent of Facilities, Coast Guard, to summarize repairs required to surplus facilities at Race Rocks prior to transfer to BC Parks. Sept. 1, 1998 Minister Anderson announces Race Rocks will be a pilot Marine Protected Area. Dec. 15, 1998 Mr. Dave Chater writes to Mr. Fred Stepchuk at Coast Guard regarding transfer of the surplus facilities. Mar. 1, 1999 Pearson College staff remain at Race Rocks although BC Parks has not reached an agreement with Coast Guard regarding the transfer of facilities. The management plan is still not finished. |

This series of documents presents an excellent chronological account of the often frustrating efforts of an organization in the community to facilitate a constructive solution to the destaffing of light stations and the simultaneous provision of on-site protection for a sensitive ecological area. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1998 | Race Rocks Ecological Reserve Management Plan the Process of Development | . | . | . | . | . | rrrefer/rrmanprocess.htm | 577.7 Fle | .CONTENTS:Part A: March 1996 : The first draft of the management plan was developed by Garry Fletcher and submitted to B.C. Parks. Part B : November 1996 : Feedback from B.C. Parks head office staff offering criticisms of the draft. Part C: February 1997: Students of the Environmental Systems class review the suggestions of B.C. Parks and propose changes and a Race Rocks permit application for research and collection activities. Part D : May 1997 : Kris Kennet of B.C. parks reworks the draft- July 14 – her final version.Part E : October 1997: invitations from Parks to Stakeholders for a meeting to discuss the draft. Part F : Written feedback of several invited people. Part G : April 1998: Draft Management Plan discussed at stakeholders meeting. Part H : June 1998 Final draft version of Management Plan produced by Jim Morris of B.C. Parks Malahat office. |

I | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L, Environmental Systems Students LBPC | 1999 | Development of a Permit Process for Race Rocks Ecological Reserve. | . | Editor:Fletcher, Garry L. | . | . | . | rrrefer/permit.htm | 577.7 Dev | From 1980 to 1999, research and educational activities in the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve have been done on a permit basis. Included in this document are samples of permits applied for through the ecological reserves office and a modified permit form presently in use by the ecological reserve- Marine Protected Area. This latter version was originally developed by two students of the Environmental systems Class at Lester B. Pearson College in 1997, Maja and Leah. | Samples of Ecological reserve permits are presented. At the Internet site, the most recent version of the permit will be available. | http://www.racerocks.com/pearson/racerock/admin/rroperat.htm | ||

| Fletcher- Garry L. | 1998 | The Underwater Safari- an Experiment in Distance Education from a Sensitive Ecosystem Using Technology | . | Editor:Garry Fletcher | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/safari/safari.htm | . | In 1994, Lester Pearson College was successful in convincing the Provincial Parks department to commit $10,000 toward the promotion of the Technology of distance education for bringing schools and the public into this sensitive marine ecological reserve. The proposal was made to the Royal B.C. Museum to use the facilities of the Jason Project to implement this plan. For one week in October, the combined resources of B.C.Tel, Shaw Cable, B.C. Systems Corp., the RBC Museum and Lester B. Pearson College were put to the test in the production of 24 1 hour live programs from Race Rocks. These programs were broadcast live by satellite and cable to schools and science centers across Canada and to the New England Science Center in the North Eastern United States. A degree of two way interaction was achieved in selected British Columbia locations. This compilation of information makes available information from the correspondence and preparatory phase as well as some of the media coverage. | In October 1992, the diving students of Lester Pearson College were able to help Darryl Bainbridge with the filming of the Canadian Underwater Safari Production . This series of 24 one hour tv programs was broadcast live from Race Rocks to schools and museum audiences across Canada and the US on the Anik 2 satellite. This experiment was the first at Race Rocks to show that technology could be used to enhance education and research in sensitive areas without them being overly threatened by the presence of humans. | . | ||

| Fletcher- Garry L., Biology and Environmental Systems Students | 1999 | Intertidal Transects at Race Rocks. | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.uwc.ca/pearson/ensy/racerock/trans98/tran15.htm | . | IntroductionThroughout the time since Lester Pearson College first took on a stewardship role at Race Rocks in the late 1970’s, we have been involved in doing a variety of Ecological studies. Tidepool monitoring, intertidal transects, invertebrate association studies , subtidal transects, and marine mammal studies. This paper will outline the Intertidal Transect-Quadrat Studies: At least 50 Students of the Environmental Systems and Biology classes annually have done intertidal transect studies as a field lab exercise. These transect studies are usually done with a class of 10-16 in a 60 minute time slot when we can get out to Race Rocks. It is only possible to do them in the spring when the tidal levels are low enough. The objectives for these studies are indicated on the worksheet attached. For the most part , they are designed to show students basic methodology of studying intertidal zonation and recording ecological changes and relationships through an environmental gradient. They are also intended however to serve a practical purpose in documenting baseline information about the intertidal area as an indicator for checking on long term patterns of change or stability and serving as a baseline against which anthropogenic changes could be measured. It is important to recognize that students are learning organism identification as well as basic technique here so there is no attempt to treat this as a rigorous statistical investigation. Two other types of transect work have been done. One is a series of photographic transects , and these have been used once as a ground truthing exercise for comparison two years after the photos were taken . The other is a transect done frequently at station 13A) on the North East corner as part of an exam question on intertidal zonation on macroalgae. CONTENTS: PART A : Intertidal transects Station #15 . Student data and kite diagrams are attached as examples. Internet connection to pictures taken during this study can be found here. (http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/transect/trans98/tran15.htm) ——————————————————————————– ——————————————————————————– |

There are many slides in the Race Rocks slide set of Garry Fletcher, stored in the Pearson College Race Rocks Collection in the library. They document various classes from Pearson College involved in doing transects. See second link to internet files. | ../transect/trans98/tran15.htm | ||

| Fletcher- Garry L., Marine Science Students, 1979 | 1979 | Ecological Reserve Proposal for Race Rocks Ecological Reserve | . | Editor:Garry Fletcher | . | . | . | rrrefer/Apr79wkshop.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | This is the proposal for the Ecological reserve at Race Rocks, done by faculty and students of Lester Pearson College, followed by a workshop held at the college in 1979. Slides of the participants may be found in the G.Fletcher slide set. | . | ||

| Fletcher- Garry L., | 1979 | The Experience of Lester Pearson College in Establishing an Ecological Reserve at Race Rocks | . | . | . | . | . | rrrefer/rrer.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | This set of papers documents some of the early experiences in working with the Parks ministry as Warden of the Ecological reserve at Race Rocks. Included are samples of correspondence, and the annual warden reports. | . | ||

| Fletcher- Garry L., Diving Service Students | 1999 | Subtidal Transects at Race Rocks | . | . | . | . | . | rrrefer/subtidtransect.htm | . | Introduction Throughout the time since Lester Pearson College first took on a stewardship role at Race Rocks in the late 1970’s, we have been involved in doing a variety of Ecological studies. Tidepool monitoring, intertidal transects, invertebrate association studies , abalone tagging, subtidal transects, and marine mammal studies. This introduction will outline the Subtidal Transect-Quadrat Studies:At least 30 Students are involved in the diving program at Lester Pearson College. One of the project we do when weather, tidal conditions and time permit is to record data on the distribution of organisms underwater at Race Rocks. Since our students are trained in diving here, they get to dive at Race Rocks after the fall training period in their first year. It is only in part of their second year that they have the necessary experience to be able to contribute to the underwater ecological recording at Race Rocks. Weather being what it is, the continuity of the work underwater is a problem and thus significant ontributions are made by a handful of students. Dives on the transect stations can only be done on a mild flood or slack tide, and since most use wetsuits, they are only able to stick with stationary activity underwater a short time until they get cold. It is important to recognize that students are learning organism identification as well as basic technique here so it cannot be treated as a rigorous statistical investigation. Various approaches have been made to standardize a workable procedure. Recently some In 1982, one set of students did a comprehensive survey of the distribution of one species Metridium senile. This was an easy to identify organism and large areas could be covered with minor difficulties. This report is included as entry #165 in the Race Rocks Ecological Overview. The data sheets for the subtidal studies are included here. It is to be hoped that someone may be able to devote the time to working them up into a series of reports on the different stations. After our experience with various methods of underwater ecological work, certainly the population studies by tagging are the ones that have been most successful. In addition, now that we have specific reference pegs in several areas along the North side of the island underwater, the monitoring of specific areas by underwater video is | – |

This is an on-going project. Raw data files are available of work done in the 1980’s.The second URL link is to the suggested procedure for any further transects that we will be doing in the future. There is a good potential here for a math studies projects using Excel database design. | rreoref2/jane/watson.htm | ||

| Slater- Carol | 1997 | Ecological Reserve Manager’s Log- 1997 | . | . | . | . | . | . | 577.7 Sla 1997 | None available– See Comments or Links | The complete text of the station log kept by Carol Slater is included in the library collection. Records of bird and mammal events, whale watching boats and fisheries infractions in the reserve are recorded | . | ||

| Slater- Carol | 1998 | Ecological Reserve Manager’s Log- 1998 | . | . | . | . | . | . | 577.7 Sla 1998 | None available– See Comments or Links | The complete text of the station log kept by Carol Slater is included in the library collection. Records of bird and mammal events, whale watching boats and fisheries infractions in the reserve are recorded | . | ||

| Slater- Mike | 1999 | Meteorological Data for Race Rocks, 1997-1998 | . | . | . | . | . | . | 551.632 Sle | None available– See Comments or Links | With the destaffing of the light station, meteorological records were about to be discontiniued. At the request of Pearson College , the records were re-established. Daily records of Max- min. temp and rainfall are included here in the library copy. An additional copy is kept at Race Rocks. | . | ||

| Slater- Mike | 1999 | Salinity- Temperature Daily Records For Race Rocks, 1997-1999 | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/data/data.htm | 551.4601 Sal | None available– See Comments or Links | Salinity records are in Density units. The raw tables submitted monthly are provided in the library in this reference. The above URL provides a link to the Institute of Ocean Sciences record made from these daily reports, dating back to the 1920’s. After automation of the light station, these records were maintained by Pearson College staff, Mike Slater. Records are taken manually one hour before high tide daily. The results are forwarded monthly to Ron Perkin of IOS. He has prepared the complete database. The link provided here also connects to an internal version of the database. | frmTemp-Salinity | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1999 | Race Rocks Ecological Reserve Warden’s Reports and correspondence 1980-1998 | . | . | . | . | . | . | 577.7 Fle Rac Ro | None available– See Comments or Links | Most of the warden’s reports available have been included | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1999 | Marine Birds of Pedder Bay to Race Rocks- Transect Data | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | None available | Includes analysis of some of the data by LBPC student David Mesiha, March 1999. Good for exercises on Excel spreadsheets. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1999 | The Management Plan for the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/manage1.htm | . | None available– See Comments | This link is to the version of the management plan for the Ecological Reserve which was completed in the spring of 1998. Another reference #27 documents the stages in the development of the plan. Also available in Braille at LBPC library. | . | ||

| Baird W.F. and Associates | 1991 | Pedder Bay British Columbia Wave Climate Study and Wave protection Considerations | . | . | . | . | . | rrrefer/pedbaywave.htm | 551.4708 Bai | None available– See Comments | . | . | ||

| Baird- Robin W., Dill-Lawrence M. | 1995 | Occurrence and Behavior of Transient killer whales: seasonal and pod-specific variability, foraging behavior and prey handling | Can. J. Zool. | . | 73 | . | 1300-1311 | . | 599.536 Bai | We studied the occurrence and behavior of so-called transient killer whales (Orcinus orca) around southern Vancouver Island from 1986 to 1993. Occurrence and behavior varied seasonally and among pods ; some pods foraged almost entirely in open water and were recorded in the study area throughout the year, while others spent much of their time foraging around pinniped haulouts and other nearshore sites, and used the study area primarily during the harbour seal (Phoca vitulina) weaning ? post-weaning period. Overall use of the area was greatest during that period, and energy intake at that time was significantly greater than at other times of the year, probably because of the high encounter rates and ease of capture of harbour seal pups. Multipod groups of transients were frequently observed, as has been reported for residents, but associations were biased towards those between pods that exhibited similar foraging tactics. Despite the occurrence of transients and residents within several kilometers of each other on nine occasions, mixed groups were never observed and transients appeared to avoid residents. Combined with previous studies on behavioural, ecological, and morphological differences, such avoidance behavior supports the supposition that these populations are reproductively isolated. |

. | . | ||

| Baird- Robin W., Dill-Lawrence M. | 1996 | Ecological and social determinants of group size in transient killer whales | . | . | . | . | . | . | 599.536 Bai E | Most analyses of the relationship between group size and food intake of social carnivores have shown a discrepancy between the group size that maximizes energy intake and that which is most frequently observed. Around southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia, killer whales of the so-called transient form forage in small groups, and appear to prey exclusively on marine mammals. Between 1986 and 1993, in approximately 434 h of observations on transient killer whales, we observed 138 attacks on five species of marine mammals. Harbor seals were most frequently attacked (130 occasions), and the observed average energy intake rate was more than sufficient for the whales energetic needs. Energy intake varied with group size, with groups of three having the highest energy intake rate per individual. While groups of three were most frequently encountered, the group size experienced by an average individual in the population (i.e., typical group size) is larger than three. However, comparisons between observed and expected group sizes should utilize only groups engaged in the behavior of interest. The typical size of groups consisting only of adult and subadult whales that were engaged primarily in foraging activities confirms that these individuals are found in groups that are consistent with the maximization of energy intake hypothesis. Larger groups may form for (1) the occasional hunting of prey other than harbor seals, for which the optimal foraging group size is probably larger than three; and (2) the protection of calves and other social functions. Key words: dispersal, foraging, group hunting, harbor seals, killer whales, optimal group size, social structure. [Behav Ecol. 7:408-416 (1996]. |

. | . | ||

| Olesiuk,Peter | 1993 | Annual Prey Consumption by harbour seals | Fish. Bull. US. | . | 91 | . | 491-515 | . | . | . | . | . | ||

| Baird, Robin W., Hanson- M.Bradley | 1996 | Status of the Northern fur seal , Callorhinus ursinus , in Canada | The Canadian Field Naturalist | . | . | . | . | rreoref2/elepseal/statusfurseal.htm | 599.79 Bai | This report reviews the general biology, status, and management of the Northern Fur Seal (Callorhinus ursinus), with special reference to its status in Canadian waters. While Northern Fur Seals do not breed within Canadian waters, they can be found in large numbers in the waters offshore of British Columbia year-round, and occasional stragglers are found inshore. Generally found only in small groups during the pelagic phase of their life, the largest numbers occur in British Columbia waters from January through June. The eastern North Pacific population has declined significantly over the last 30 years, but the cause in unknown. |

The picture shown here is of the fur seal “Frosty” who Trev and Flo Anderson took note of for at least six years at Race Rocks- until they left in 1982. Photo by Flo Anderson | . | ||

| Baird- Robin W. | 1997 | Birth of a Resident killer whale off Victoria , British Columbia ,Canada | Marine Mammal Science | . | 13 | 3 | 504-508 | . | 599.523 Bir | Observations of cetacean births are rare, as are reports of the behavior of the mother and other group members immediately after a birth. Scientists have observed births of at least five species in the wild: the killer whale (Orcinus orca), sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), beluga (Delphinapterus leucas), false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens), and gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) ( Balcomb 1974, Leatherwood and Beach 1975, Mills and Mills 1979, Jacobsen 1981, Weilgart and Whitehead 1986, Beland et al. 1990, Notarbartolo-di-Sciara et al. 1997). There have also been a few published accounts of cetacean births in captivity (e.g., Asper et al. 1988). This note describes the birth of a wild killer whale in a well-documented “resident” pod and the unusual behavior of the group. |

. | . | ||

| Baird-Robin W. | 1998 | Dall’s porpoise reactions to tagging attempts using a remotely- deployed suction -cup tag | MTS Journal | . | 32 | . | 18-23 | . | 599.53 Han | Remotely-deployable non-invasive (suction-cup attached) tags to record underwater behavior of cetaceans have recently been developed. How useful these tags are for applications on a broad range of species has yet to be documented. However, we attempted to use such tags to study the diving behavior of Dall’s porpoise (Phocoenoides dalli) in the trans-boundary area of British Columbia and Washington state, and report here on the feasibility of the technique, including the reactions of Dall’s porpoise to tagging attempts. Tagging activities were undertaken in August 1996, while porpoises were bow-riding on a small vessel. We made 15 tagging attempts and 13 resulted in tag contact with a porpoise. No reactions were observed for the 2 misses, nor for 2 of the 13 hits. Of the 11 cases when tag reactions were observed, porpoises returned to continue bow-riding almost immediately in 7 cases, suggesting no long-term effect. Short-term reactions observed included a flinch (9 of 13 hits), tailslap (1 of 13 hits) and high speed swimming away from the vessel (4 of 13 hits), with some hits resulting in more than one type of reaction. Three of 13 hits resulted in successful tag attachment. One tag remained attached for 41 minutes, providing the first diving behavior data for this species. Rates of descent and ascent, as well as swimming velocity, were relatively high only for the first 6-8 minutes after tag attachment, suggesting a reaction to tagging that lasted approximately 8 minutes. |

. | . | ||

| Baird-Robin W. | 1998 | An Intergenic hybrid in the family phococnidae | Can Journal Zool | . | 76 | . | 198-204 | . | 599.539 Bai | A 60 cm female fetus recovered from a Dall’s porpoise (Phocoenoides dalli) found dead in southern British Columbia was fathered by a harbour porpoise (Phocoena Phocoena). This is the first report of a hybrid within the family Phocoenidae and one of the first well-documented cases of cetacean hybridization in the wild. In several morphological features, the hybrid was either intermediate between the parental species (e.g., vertebral count) or more similar to the harbour porpoise than to the Dall’s porpoise (e.g., colour pattern, relative position of the flipper, dorsal fin height). The fetal colour pattern (with a clear mouth-to-flipper stripe, as is found in the harbour porpoise) is similar to that reported for a fetus recovered from a Dall’s porpoise to off California. Hybrid status was confirmed through genetic analysis, with species-specific repetitive DNA sequences of both the harbour and Dall’s porpoise being found in the fetus. Atypically pigmented porpoises (usually traveling with the behaving like Dall’s porpoises) are regularly observed in the area around southern Vancouver Island. We suggest that these abnormally pigmented animals, as well as the previously noted fetus from California, may also represent hybridization events. |

. | . | ||

| Baird- Robin,W | 1998 | Studying Diving Behavior of Whales and Dolphins using suction cup attached tags | Whalewatcher | . | Spring/Summer | . | 3-7 | . | 599.53 Bai S | Tagging whales with radio transmitters (either VHF or satellite-linked) or sensors which record depth, swimming speed, or other parameters can provide details on the movement patterns and behavior of a species. Methods for putting such tags on whales and dolphins have typically involved capturing the animals and pinning the tags onto the dorsal fin of dorsal ridge, or using tags which can be put on free-living animals but which penetrate the skin to anchor into the blubber. While these methods are necessary in many studies, especially for those in which long-term or long-distance information is required, there is an alternate method for short-term attachments which does not require capturing the animals or penetrating the skin. This approach uses remotely-attached suction-cup tags. Here I give information on the history of this technique, some details about methods, and talk about some of the limitations. Despite the potential situations where suction-cup tags may be valuable or even the most “appropriate” method for attaching instruments on cetaceans, many limitations to this method exist. |

. | . | ||

| Bigg- Michael | 1985 | Status of the Steller Sea Lion ( Eumetopias jubatus) and California Sea Lion ( Zalophus californianus) in British Columbia | Canadian Special Publication of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences | . | . | . | 20 | . | 599.5 Big | None available– See Comments or Links | . | . | ||

| Barr- Julie | 1996 | Interests of Stakeholders and options for Establishing a Marine Protected Area at William Head- A Discussion Paper | Discussion paper | . | . | . | . | rrrefer/wmhead.htm | 577.7 Bar I | None available– See Comments or Links | Appendix contains two journal articles on Marine protected Areas | . | ||

| MPA Strategy Steering Committee , B.C.Parks , Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 1998 | Marine Protected Areas A Strategy for Canada’s Pacific Coast– Discussion Paper | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.luco.gov.bc.ca/pas/mpa/dispap.htm | 577.7 Pet | None available– See Comments or Links | Co-signed by Petrachenko-Donna, and Thompson-Derek -From the Foreword: “This Strategy has been developed jointly by federal and provincial agencies and clearly reflects the need for governments to work in unison to achieve common marine protection and conservation goals. The Strategy is not a new program, but an initiative to coordinate all existing federal and provincial marine protected areas under a single umbrella. This will allow for the development of a national system of marine protected areas on the Pacific Coast by the year 2010 which is interlinked with the marine components of the B.C. Protected Areas Strategy.” August, 1998 | . | ||

| Stitt-Susan | 1990 | Lighthouse keepers essential to research | Pacific Tidings | . | 3 | 3 | 4-6 | . | 387.155.Sti | None available– See Comments or Links | “We see clear evidence of a warming trend in the ocean,” says Dr. Freedland. “The trend line shows warming at Race Rocks to be about .26 degrees C. per century, that’s quite small but the water there is influenced by the Frazer River and the cold water coming down off the mountains,” | . | ||

| Seven-Richard | 1998 | Keepers of the Light– After years of protecting people from these rocks, these lighthouse keepers now protect the rocks from the people | Pacific Northwest magazine in The Seattle Times– January 25, 1998 | . | . | . | . | . | 387.155 Sev | None available– See Comments or Links | Has excellent color photos | . | ||

| Hodgkins-D.O., Goodman-R.H., Fingas, M.F. | 1993 | Forecasting Surface Currents Measured with HF Radar | Proceedings 16th Arctic and Marine Oil Spill Program (AMOP) Technical Seminar | . | . | . | 12 | . | 551.4701 Hod | Utilization of real-time surface current data with oil spill models requires forecasting currents for lead times of 24 to 48 hours. A forecasting method based on tidal decomposition and an ARMA analysis of residuals has been derived and tested using the 1992 Juan de Fuca SeaSonde database of hourly surface currents. Results show that, for this particular region, most of the observed current can be accounted for by the tide and the short-term residual mean. A portion, representing about 15% of the variance, was found to be associated with the turbulent eddy field. The radar current measurements provide spatial estimates of the kinetic energy in this turbulent component, and of the associated eddy diffusivity. Thus, the current forecasting algorithm provides useful predictions of both the slowly-varying deterministic flow field, and the spatial variations of the turbulent energy and diffusivity. |

. | . | ||

| Jaquette, Leslie | 1995 | In a league of their own | Canadian | . | April | . | 35-37 | rreoref/league/league.htm | 577.7 Jac | None available– See Comments or Links | An article about this area as a diving destination. Translation into French in “La Reserve ecologique de Race Rocks” parallel article. | . | ||

| Baird- Robin W. | 1991 | Harbour Seal Detection of Predators: Implications for the adaptive function of transient killer whale foraging tactics. | Research Proposal | . | . | . | 19 | . | 595.5 Bai Ha | Two forms of killer whale (Orcinus orca) are found in British Columbia, Alaska and Washington; one, termed transient, feeds primarily on marine mammals, and the other, termed resident, feeds primarily on fish. In the study are around southern Vancouver Island, transient killer whales feed primarily on harbour seals (Phoca vitulina). The purpose of this research is to examine each of the three sensory cues harbour seals might use to detect killer whales. These cues are (1) visual, (2) auditory above-water, and (3) auditory below-water. The relative importance of each cue in harbour seal detection of killer whales will be determined by comparing the magnitude of the reactions to each stimulus. While hunting harbour seals, transient killer whales exhibit characteristics of all of these components (visual and above- and below-water sounds) that differ from those of (fish-eating) residents. These are : an increased length of long dives (Morton 1990) ; decreased amplitude of exhalations (blows) (Baird pers. obs.) ; and a lack of underwater vocalizations (Ford and Hubbard-Morton 1990). These behavioural differences may be adaptations which function to decrease detection by seals, but this has not been tested. |

This proposal includes the permit application. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. , Marine Science Students LBPC | 1979 | Race Rocks Ecological Reserve Proposal- Lester B. Pearson College | Report | . | . | . | 67 pages | rrrefer/Apr79wkshop.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | This represents the original proposal for protected status at Race Rocks. It was done by Garry Fletcher and the Marine Science students of Lester Pearson College in preparation for a workshop held on the subject at Pearson College April 21 1979. Complete text of the proposal is included at linked site below. Includes Appendices and record of the workshop meeting at Lester Pearson College. Slides of this event are contained in the slide file referenced in this database. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L, Marine Science Students -LBP College | 1980 | Race Rocks Ecological Reserve : Application, Ministry Executive Committee Submission, Cabinet Submission and Correspondence 1979-1980 | . | . | . | . | 60 | rrrefer/Apr79wkshop.htm | 577.7 Fle R | None available– See Comments or Links | In the picture, Dr. Derrick Ellis of U.Vic at the Race Rocks Workshop discussing with Garry Fletcher, students, and other invited guests the possibility of creating an ecological reserve for Race Rocks (April of 1979.) | . | ||

| Van Dam- Frank, Bethel-Nico,Couchman Barbara, May-Fiona | 1977 | Historical Documentation on Race Rocks | Student Reports | . | . | . | 12 | . | 387.155 Van | None available– See Comments or Links | . | . | ||

| Wallace- S.Scott | 1996 | Initial Communications and Findings of Abalone Project – Race Rocks | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | None available– See Comments or Links | This set of references includes the permit application and information sent back to Pearson College while Scott was working on his graduate work at UBC. | . | ||

| Watson- Jane | 1994 | Race Rocks Sampling Program | . | . | . | . | 14 | rreoref2/jane/lngmonitor.htm | 577.7 Wat | None available– See Comments or Links | This report was done by Jane Watson of Malaspina College in Nanaimo in order to help the students at Pearson College establish a sampling protocol for the stainless steel pegs established from 1994-1995. It is followed up with a survey done by Javier Blanco in 1997 that helps to define the exact location of the pegs. | . | ||

| Cornerstone planning Group | 1996 | A Preliminary Assessment of Potential Alternative Uses for Light stations in B.C. | . | . | . | . | . | . | 387.155 Pre | The site is situated within an Ecological Reserve, which is a nesting area for thousands of seagulls and other sea birds, including oyster catchers and cormorants. The presence of a sea lion haul-out site and elephant seals means that the site may be noisy during certain times of the year. There is easy access from Victoria harbour. The site is currently used by Pearson College for research and educational purposes, and used by nine whale-watching companies for marine wildlife viewing. There is good potential for local sea kayaking tours, and it is currently used as a scuba diving site. The Royal B.C. Museum and other local tour operators visit Race Rocks. The barren landscape with much wind and lack of potable water are not conducive to the camping experience. |

Page 34 note; potential Alternative uses. This rather glib assessment of the potential shows a | . | ||

| Crawford -John | 1998 | Race Rocks project-Phase II- An Examination of Technical Connectivity issues and Educational Options | . | . | . | . | 12 | . | 374.26 Cra | None available– See Comments or Links | Phase I of the Pearson College / Open School collaboration on Race Rocks (completed March 31, 1998), established a strong link between the British Columbia science curriculum and the abundant marine resources of the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve. The compatibility of educational need and a rich marine resource led to the issue of defining specifics for connectivity.The objective of Phase II (summer, 1998) was to identify technical connectivity needs and costs, and consider alternate education options.

Not infrequently, what appears to be a straight forward data gathering However, significant progress was made. Detailed below is : – a summary of the considered opinions of many experts on the and, – recommendations for a two-pronged approach to achieve the long-term |

. | ||

| Matthews -Angus | 1997 | Race Rocks Contemporary History | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | None available– See Comments or Links | Records events at Race Rocks, mostly as they related to the staff and students of Lester Pearson College. In the picture shown here. Trev and flo Anderson built the ship “Wawa” in the late 1970’s and launched it in 1982.– pictures included in this web site. | . | ||

| Matthews- Angus | 1997 | Race Rocks History | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/history/rrkeeper/histcont.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | On this site is an excellent set of black and white photographs taken of Race Rocks in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s . Courtesy of the British Columbia Archives. Victoria, B.C. | . | ||

| Bibby- Allan | 1997 | Outpost Video -The Race Rocks Marine Education Centre | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/outpost/rreduc.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | Two versions of this film exist, an 11 minute and a 6 minute version. It highlights Dr. Joe MacInnis on his dive at Race Rocks with students of Lester Pearson College. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1996 | Race Rocks Ecological Reserve History | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/rrerhist.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | A summary of the process of making the ecological reserve. In the photo, Jens Jensen and johan Ashuvud, students in the Diving Service of Pearson College are fixing a marker bouy on Rosedale reef. This was at a negative tidal level, the only time in some years this reef becomes visible for a few minutes. Also see slides in the slide collection. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1997 | Race Rocks to be Managed by Pearson College | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/news/racenews.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | Announcement on Internet | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1996 | The Race Rocks Ecological Reserve Information Pamphlet | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/racrksre.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | VISITING THE ECOLOGICAL RESERVE: Hazards, Light Station, Marine Mammals and Sea Birds, Anchoring, Fishing, Collecting, Research, Diving, Kayaks , Canoes,and Small Boats, Weather, Tides and Currents, Research and Education, Permits– This internet site gives a complete summary of information on the reserve for visitors. |

. | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1997 | The Race Rocks Foghorn | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/sounds/foghorn.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | You can download the sound of the old foghorn as it was before 1997. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1996 | Underwater Safari Project at Race Rocks | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/safari/safari.htm | . | THE UNDERWATER SAFARI PROJECT In October of 1992, the diving students of Pearson College were able to help with the underwater filming for the Canadian Underwater Safari production. This series of 24 one hour television programs was broadcast live to schools and museum audiences across Canada and the US on the Anik E2 Satellite. Since that time the programs have been broadcast across the world. We have made available at this location some of the unique unerwater footage which was taken by the photographer Darryl Bainbridge. The project was an experiment in using technology along with many volunteer hours to help to bring the fragile ecology of this unique area to the world. Our thanks to B.C.Parks for the intial funding to launch the production. The Royal B.C. Museum and its staff , Shaw Cable, BCSystems, BC Tel and many volunteers who provided assistance with this project. |

Jason Reid, a Pearson College Diver stares down the wolf eel on live televised footage at the time of the Underwater Safari Project. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1997 | Biology Class doing Intertidal Transects at Race Rocks- 1997 | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/tidepool/biotran/biotran.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | Work on peg #15 .. Largely photographic, but it links to other quantitative data on the intertidal transects | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1995 | Race Rocks Ecological Reserve Transect File | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/transect/transrrk.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | This is a web site devoted to recording photographic records of transect information so that it can be analyzed with a computer. Three photographic strips taken in 1995 in the intertidal zone near peg#5 at Race Rocks are the samples included. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1997 | Research at Race Rocks | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/admin/erpropos.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | An account of some of the recent projects at Race Rocks. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1998 | Rare Observations at Race Rocks | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/pearson/racerock/rare/rare.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | This is a file we keep on the internet of rare occurrences at Race Rocks. Examples are: Brown Pelicans, the gastropod mollusk “Opalia. sp.”, the Northern Fur Seal, and a rare land plant, Romanzoffia tracyi. | . | ||

| CoastWatch Students and Garry Fletcher | 1997 | The Schools Project | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/cw/schools/school.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | An account of the Schools project , which is conducted each spring by the Divers at Pearson College. Links to the schedule, whale exercise and description of the stations on the field trip. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1997 | Dr. Anita Brinckmann-Voss – The hydroid file | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/hydroid/anitabv.htm | . | Since 1986, Dr. Anita Brinckmann-Voss has assisted the students and faculty of Lester Pearson College with her understanding of marine invertebrate ecology and her expertise in the taxonomy of hydroids. These small colonial animals, the alternate stage of the life-cycle of jellyfish, occur in rich profusion underwater at the Race Rocks Marine Ecological Reserve.When the original species list was done for the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve Proposal, in 1979, only 2 hydroids had been included on our species list. Now over 60 species have been identified by Anita and she continues to assist students with research projects while she furthers her research on specimens from the island. Anita has established long term research plots in a tidepool at the reserve and documents the distribution of hydroids underwater with the assistance of students and faculty in the Diving program at Lester B. Pearson College. | A file containing references and photographs of some of the work of Anita Voss at Race Rocks. Also included are examples of biotic associations of hydroids with other invertebrates. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L., | 1997 | Ecological Niche , The Empirical Model | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/transect/econiche/econiche.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | This web site is a suggestion for a field lab on ecological niches of organisms. Photos from Race Rocks intertidal zone are used as a sample of the process — level Grade 11-12 and up. | . | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1998 | The Race Rocks Physical Data File | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/data/data.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | This file is for linking to a number of sites with current and past records and predictions of physical factors | . | ||

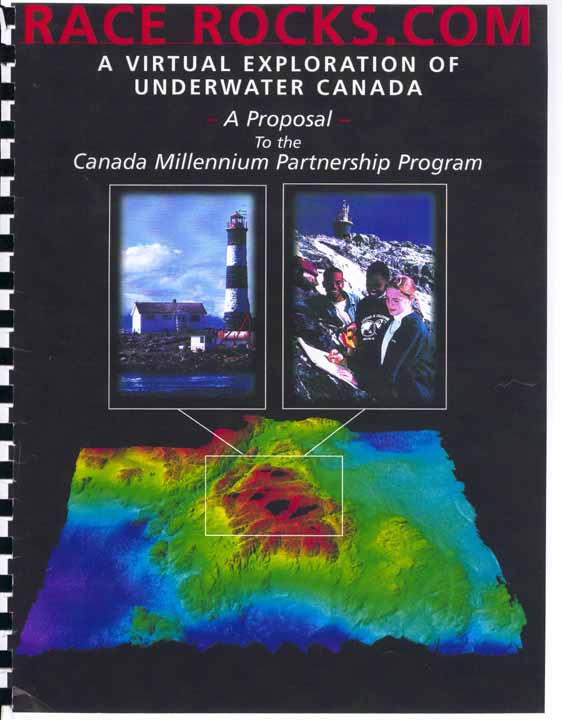

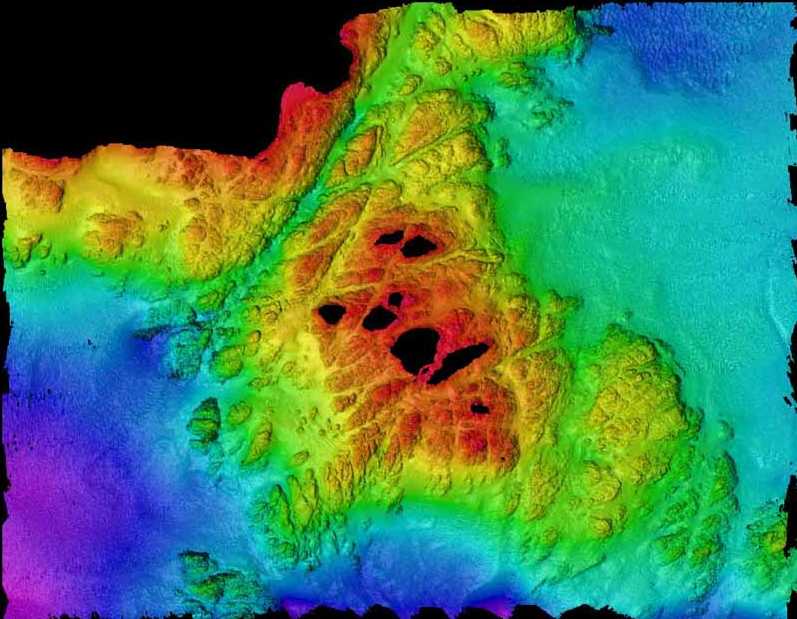

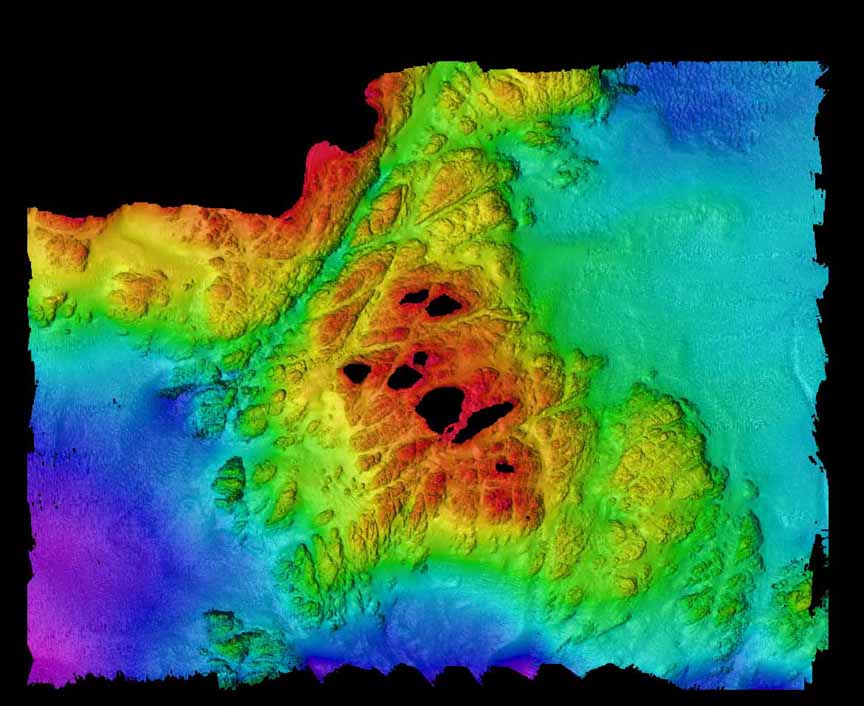

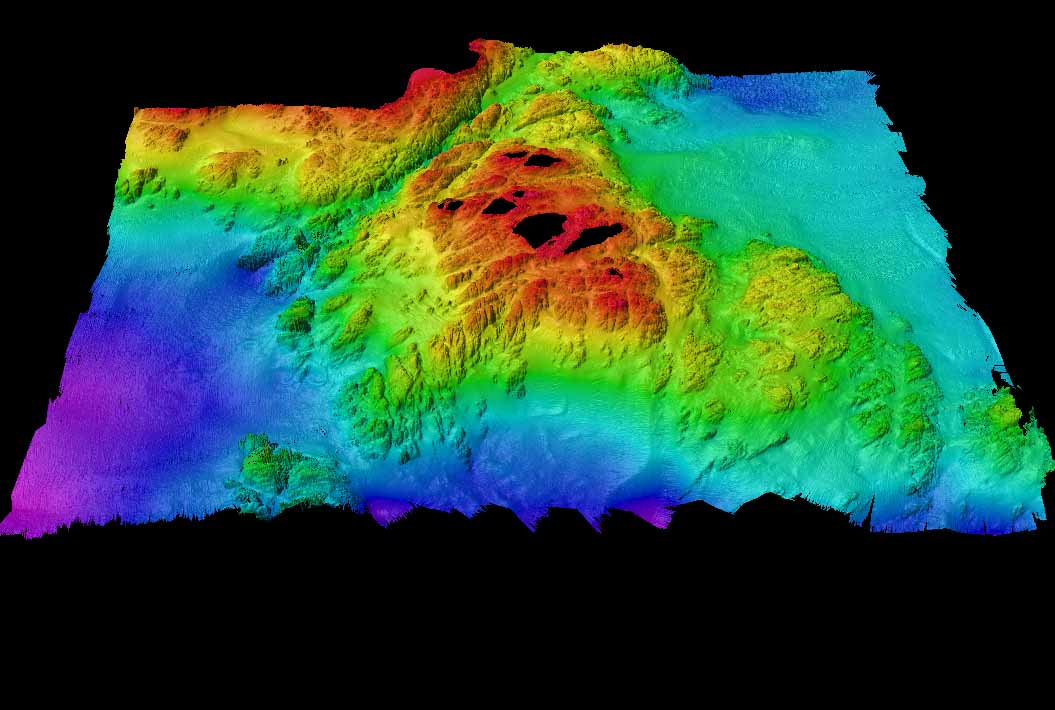

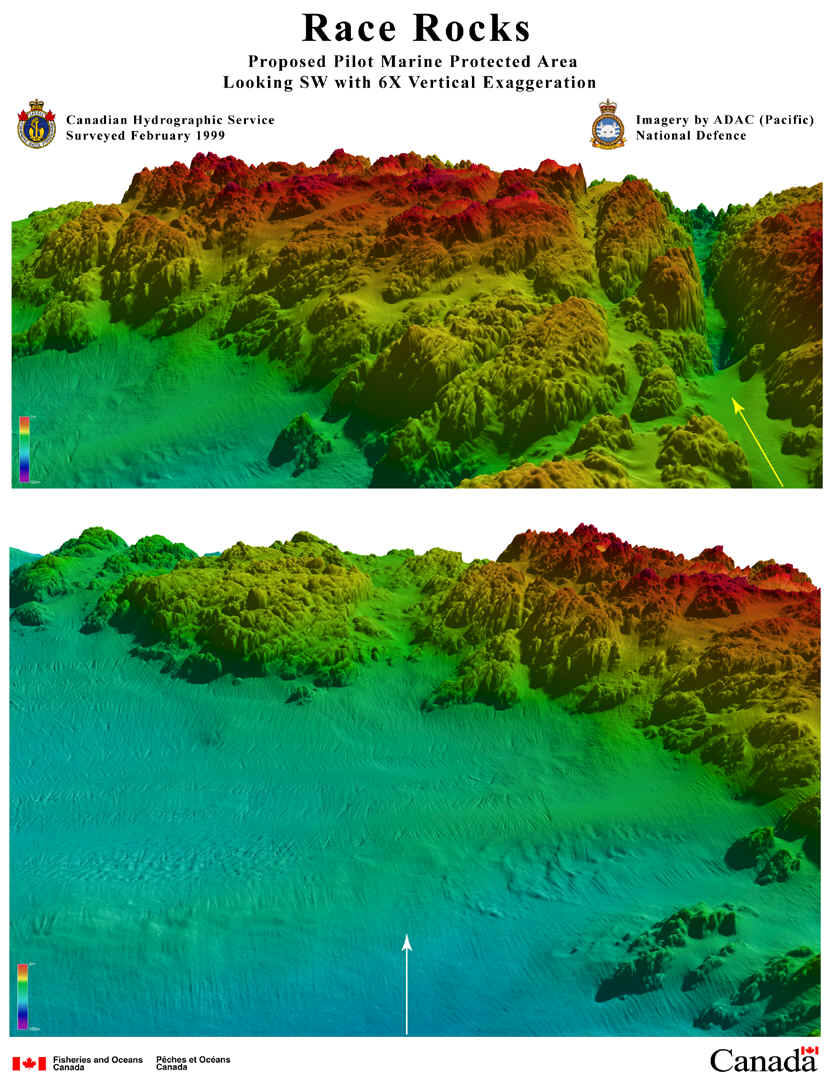

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1997 | Underwater 3D at Race Rocks | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/roxview/roxview.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | The image of underwater topography of the Race Rocks MPA on this site was made by Terra Surveys of Sidney, B.C. | . | ||

| Brinckmann-Voss – Anita | 1990 | Permit Reports and Correspondence for Hydroid research | . | . | . | . | 22 | . | 593.55 Bri P | None available– See Comments or Links | Included are copies of some of the permit applications made by Anita Voss for her work in conjunction with the Pearson College Diving Students and Faculty at Race Rocks Ecological Reserve. Also included are the draft materials for her paper on the tidepool #6 .- Seasonality of hydroids— Species lists are included. Entries span 1986 to 1890 | rreoref/manage1.htm | ||

| Fletcher-Garry L. | 1997 | The Group Four Science Project at Race Rocks – 1997 | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/GRP4/gr4frameset.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | . | . | ||

| Ecological Reserves Branch. | 1995 | B.C. Ecological Reserves Brochure and map | . | . | . | . | . | http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/brochur2.htm | . | None available– See Comments or Links | Introduction to Ecological reserves in BC Listing of 131 reserves and a map as to the distribution in 1993. | . | ||

| Ecological Reserves Branch | 1995 | Race Rocks Ecological Reserves #97 Publications List | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | None available– See Comments or Links | The ecological reserves office of the Provincial Department of Lands and Parks have since the inception of the reserve in 1980 kept a copy of all reports done that relate to research done on the reserve. At present this is housed at the Parks Office at 700 Johnson Street in Victoria.. All the records from this site have been added to this database . Copies of the reports will be available also at both libraries. | . | ||

| Hawkes -Michael W | 1994 | Conserving Marine Ecosystems: Are British Columbia’s Marine Protected Areas Adequate? (Chapter 28) | Biodiversity in British Columbia | Editor: Harding, Lee E. , McCullum, Emily | . | . | 393-410 | rrrefer/biodch28/biodiversitychapt28.htm | 577.7 Haw | None available– See Comments or Links | (From page 399) Race Rocks ( Ecological Reserve # 97 ) in the Strait of Juan de Fuca has the most protected status of any marine protected area in the province. It is closed ( by the department of Fisheries and Oceans) to the commercial and recreational harvesting of all marine life except for recreational (sport) fishing of salmon and halibut. The reasoning behind this decision is that salmon and halibut are migratory finfish and therefore transient in the reserve, so closing these fisheries in the reserve will do nothing to conserve the species. However accidental catch of resident fish in the reserve , especially rockfish , is a matter of concern. | rrrefer/biodch28/p232complete.htm | ||

| Dickins- David, British Columbia Env. Emergencies and Coastal Protection | 1990 | Oil Spill Atlas | Oil spill response atlas for the southwest coast of Vancouver Island | Editor: D. Dickens | . | . | . | . | 628.1686 Oil | None available– See Comments or Links |

NOTES: Includes bibliographical references. SUBJECT: Environmental protection–British Columbia–Vancouver Island–Maps. SUBJECT: Oil spills–Environmental aspects–British Columbia–Vancouver Island–Maps. SUBJECT: Oil pollution of the sea–Environmental aspects–British Columbia–Vancouver Island–Maps. |

. | ||

| Holbrook- J.R. et al | 1980 | Circulation in the Strait of Juan de Fuca : recent oceanographic observations in the eastern basin | . | . | . | . | . | . | 551.47 Hol | None available– See Comments or Links | . | . | ||

| Frisch- Shelby, Holbrook- James | 1978 | HF RADAR measurements in Eastern Juan de Fuca | HF radar measurements of circulation in the eastern Strait of Juan de Fuca (August, 1978) |

. | . | . | . | . | . | None available– See Comments or Links | The results of the harmonic analysis of data from 95 tide stations and 90 current stations in the Strait of Juan de Fuca Strait of Georgia system are presented in the form of tables, cotidal and corange charts, and charts illustrating the relationships between various tidal constituents. The implications of these results relative to the tidal hydrodynamics of the system are discussed generally. Methods of analysis are described. A physical description of the area is also given along with approximate values of transport through key cross sections.Since the fall of 1973 the National Ocean Survey (NOS) has been carrying out detailed circulatory surveys in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Strait of Georgia, and connecting waterways. The object of these surveys (six of which have been completed at the writing of this report) has been the acquisition of tide, current, and salinity and temperature data at numerous locations and depths, along with weather data such as wind, sea level pressure, and air temperature. Analysis of these data is expected to provide an accurate and detailed description of water movement in this area, as well as further theoretical insight into the causes of this water movement. The need for increased understanding of the Strait of Juan de Fuca Strait of Georgia system is due in part to the increased oil tanker traffic from the Trans-Alaskan pipeline to the several refineries in this area and in Puget Sound to the south (connected to the Strait of Juan de Fuca by Admiralty Inlet). Damage to the marine environment from oil spill could have serious detrimental effects on the large salmon and shellfish industries and on the even larger commercial fishing and recreation industries. A better understanding of the water movement in this area is expected to minimize the consequences of oil spillage and maximize the effectiveness of cleanup operations. It will also provide information relevant to municipal pollution problems, coastal zone management, and navigation. The data from these surveys (officially designated, OPR-509, Puget Sound Approaches) have come mainly from the eastern half of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, including Admiralty Inlet, the southern end of the Strait of Georgia, and the connecting waterways. This area is the most dynamically complicated portion of the system. These data have been supplemented |

. | ||

| Nyblade -Carl F. | 1978 | The intertidal and shallow subtidal benthos of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, spring 1976 -winter 1977 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | None available– See Comments or Links | . | . | ||

| Vanderhorst-J.R., | 1980 | Recovery of Strait of Juan de Fuca intertidal habitat following experimental contamination with oil : second annual report, fall 1979 – winter 1980 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | None available– See Comments or Links | . | . | ||

| British Columbia/Washington Marine Science Panel. | 1994 | The shared marine waters of British Columbia and Washington a scientific assessment of current status and future trends in resource abundance and environmental quality in the Strait of Juan De Fuca, | . | . | . | . | . | . | 577.7 Sha | The British Columbia/Washington Marine Science Panel was created in 1993 under the 1992 Environmental Cooperation Agreement between British Columbia and Washington state. The panel was asked to evaluate the condition of the marine environment in the Strait of Georgia, Strait of Juan de Fuca and Puget Sound region on both sides of the international boundary. For purposes of this report, this region is called the shave waters, and the area in the immediate vicinity of the international boundary is called the transboundary waters.The panel reports to the British Columbia/Washington Environmental Cooperation Council, which was formed as part of the Environmental Cooperation Agreement and which identified water quality on both sides of the boundary as a high-priority issue requiring immediate and joint attention. To guide its inquiries, the panel addressed several questions about natural processes, resource population, contamination and future trends in the area. In early 1994, the panel participated (with a Work Group supporting the Environmental Cooperation Council) in a scientific symposium featuring invited presentations by Canadian and U.S. scientific experts on a broad range of topics. The scientific review papers from this symposium have been published as a separate technical volume and form an important basis for this report. The panel based its recommendations about conditions in the shared |

The shared marine waters of British Columbia and Washington a scientific assessment of current status and future trends in resource abundance and environmental quality in the Strait of Juan De Fuca, Strait of Georgia, and Puget Sound :British Columbia/Washington Marine Science Panel. |

. | ||

| Chester – Alexander J | 1978 | Microzooplankton in the surface waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca | . | . | . | . | 25 | . | 592.1776 Che | None available– See Comments or Links Microzooplankton organisms were enumerated from surface seawater samples obtained at three stations in the Strait of Juan de Fuca during 13 cruises from 1976 to 1977 (tabulated data appear in Appendix). Ciliates were the most abundant group; maximum concentrations exceeded 10,000 liter. The ciliate community was composed almost exclusively of oligotrichs, tintinnids, and the gymnostome species, Mesodinium rubrum. These groups made up an average of 60%, 10%, and 30%, respectively, of the total ciliate numbers at each station. Twenty-six tintinnid species and 15 oligotrich species were identified during the 2-year study. The population peaks of most of these organisms coincided with periods of high biological activity during spring and summer. Certain species, however, such as the tintinnid Stenosemella ventricosa, were most common during winter months. The ecological role of oligotrichs and tintinnids as particle grazers is distinguished from that of M. rubrum, a ciliate deriving its nutrition from photosynthetic endosymbionts. |

NOAA technical report ERL-PMEL- | . | ||

| Sutherland, I. R. | 1989 | Kelp inventory, 1988 : Juan de Fuca Strait | Fisheries Development Report -No 35 | . | . | . | 18 | . | . | None available– See Comments or Links | (Fisheries development report. no. 35.) Six folded maps in pocket. 17 pages Includes bibliographical references. 1. Nereocystis luetkeana–Juan de Fuca Strait (B.C. and Wash.) 2. Macrocystis integrifolia–Juan de Fuca Strait (B.C. and Wash.) 3. Nereocystis luetkeana–British Columbia. 4. Macrosystis integrifolia–British Columbia. I .British Columbia. Aquaculture and Commercial Fisheries Branch. |

. | ||

| Parker- Bruce B | 1977 | Tidal hydrodynamics in the Strait of Juan de Fuca – Strait of Georgia | (NOAA technical report ; NOS 69) Item 208-B-7. S/N 003-021-000165. | . | . | . | 56 | . | 551.4708 Par | None available– See Comments or Links | 1. Tides–Juan de Fuca (Strait). 2. Tides–Georgia, Strait of. I. National Ocean Survey. Office of Marine Surveys and Maps. II. United States. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. | . | ||

| LeBlond – Paul H. | 1987 | A Review of the impact of Unmanning Western Region Lightstations A review of the impact of unmanning western region light stations: final report |

. | . | . | . | 30 | . | 387.155 Lab | This report reviews the activities of lightkeepers at B.C.’s 41 manned lightstations, with particular emphasis on safety-related services such as weather reporting, search and rescue, and radio communications. The impact of removing the keepers on the functioning of navigational aids and on safety-related services has been assessed through a series of interviews with Canadian Coast Guard officials as well as representatives from other federal government departments and through consultation with the coastal marine community in public meetings and private interviews.Sufficient evidence has been found to conclude that a human presence is not absolutely necessary to keep lights and foghorns functioning at a satisfactory level of reliability; automatic lightstations are already common in Canada and elsewhere. The most significant impact of removal of a lightkeeper is thus to be found on the level of safety-related services provided at a given lightstation. Digests of keepers logs, plans of government departments, availability of alternate resources and users views have been consulted for each type of service (weather, SAR and radio) for each station. Stations have been grouped in four classes according to the assessed impact of unmanning Stations with Medium impact index should be kept manned for now, but |

. | . | ||

| Collias – Eugene E. McGary v- Noel , Barnes – Clifford A. | 1974 | Atlas of Physical and Chemical Properties of Puget Sound and Its Approaches | Washington Sea Grant Publication | . | . | . | . | . | 551.4601 Col | Objective; Physical and Chemical oceanographic Data from Puget Sound and its approaches have been gathered by the university of Washington since 1932, these data have been published in tabular form and have been catalogued by Collias (1970) , but little of this information has been put into a graphic form that is readily available. This Atlas of Physical and chemical properties of Puget Sound and its Approaches makes such a graphic presentation and provides a convenient and usable reference for defining the major features of water properties in the Sound. | Data and cross sectional charts measured from 1952- Oct 13-16 until Nov. 13 1961 RR no stations occupied until Feb. 16-19 1953 The following Vertical profile charts are made available: Temperature, Salinity, Density, Phosphate, and Oxygen. | . | ||