p.401 , Vol 71, 1993 Rhysia fletcheri (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa, Rhysiidae), a new species of colonial hydroid from Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada) and the San Juan Archipelago (Washington, U.S.A.)A. BRINCKMANN-VOSS

Department of lnvertebrate Zoology, Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queen’s Park, Toronto, Ont., Canada M55 2C6And D. M. LICKEY AND C. E. MILLS, Friday Harbor laboratories, University of Washington, 620 University Road, Friday Harbor, WA 98250, U.S.A.Received February 28, 1992 Accepted September 17, 1992BRINCKMANN-VOSS, A., LICKEY, D. M., and MILLS, C. E. 1993. Rhysia fletcheri (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa, Rhysiidae), a new species of colonial hydroid from Vancouver Island (British Columbia, Canada) and the San Juan Archipelago (Washington, U.S.A.).

Can. J. Zool. 71: 401-406.

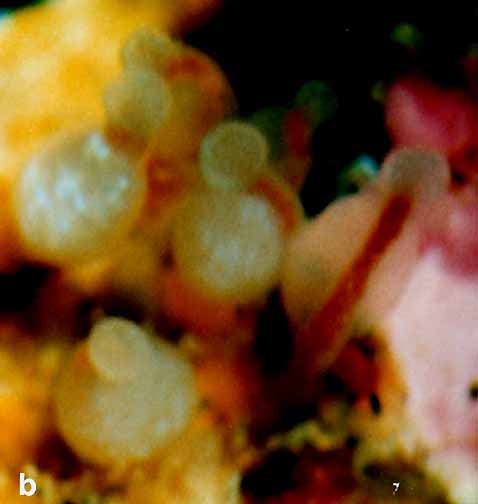

A group of females A new species of colonial athecate hydroid, Rhysia fletcheri, is described from Vancouver Island, British Columbia Canada, and from Friday Harbor, Washington, U.S.A. Its relationship to Rhysia autumnalis Brinckmann from the Mediterranean and Rhysia halecii (Hickson and Gravely) from the Antarctic and Japan is discussed. Rhysia fletcheri differs from Rhysia autumnalis and Rhysia halecii in the gastrozooid having distinctive cnidocyst clusters on its hypostome and few, thick tentacles. Most of its female gonozooids have no tentacles. Colonies of R. fletcheriare without dactylozooids. The majority of R. fletcheri colonies are found growing on large barnacles or among the hydrorhiza of large thecate hydrozoans. Rhysia fletcheri occurs in relatively sheltered waters of the San Juan Islands and on the exposed rocky coast of southern Vancouver Island.

c. (a group of males.. relaxed)  b. -( group of males ..contracted.)

On trouvera ici la description d’un nouvelle espece d’hydroide colonial sans theque. Rhysia fletcheri, trouvee dans l’ile de Vancouver en Colombie-Britannique, Canada, et a Friday Harbor, Washington, Etats-Unis. Sa relation avec Rhysia autumnalis Brinckmann en Medlterrannee et Rhysia halecii (Hickson and Gravely), de l’Antarctique et du Japon, fait l’objet d’une discussion. Rhysia fletcheri differe des deux autres especes par la presence chez le gastrozooide de faisceaux tres particuliers de cnidocystes sur l’ hypostome et de tentacules epais et peu nombreux. La plupart des gonozooides femelles sont depourvus de tentacules. Les colonies de R. fletcheri ne comportent pas de dactylozooides. La majorite des colonies de R. Fletcheri crois sent sur les grosses balanes ou parmi les hydrorhizes des gros hydrozoaires a theque. Rhysia Fletcheri se trouve dans les eaux relativement protegees des iles San Juan et sur la cote rocheuse exposee du sud de l’ile de Vancouver. [Traduit par la redaction.] |

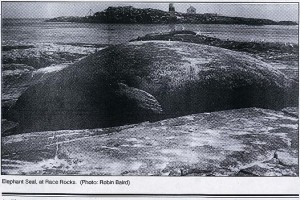

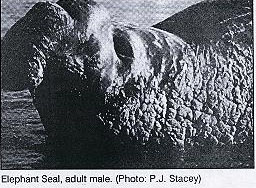

Introduction:Colonies of a hydroid species belonging to the genus Rhysia Brinckmann, 1965 were collected off Friday Harbor in Washington State, U.S.A., from 1972 to 1992. They were found in tide pools at Race Rocks, British Columbia, Canada, and from adjacent coastal regions of Vancouver Island between 1986 and 1992. The species is referable to the hydrozoan family Rhysiidae, and to the genusRhysia, in having gonads within the body wall along one side of the gonozooid. However, it differs from previously described species of the genus in having cnidocysts arranged in clusters on the hypostome of the gastrozooid, and in having fewer and thicker tentacles on the gastrozooid, and no dactylozooids. The purpose of this paper is to provide a systematic and ecological account of Rhysia fletcheri sp.nov. The species is compared with Rhysia autumnalis Brinckmann, 1965, type species of the genus Rhysia, and with Stylactis halecii Hickson and Gravely, 1907. The latter species has lateral gonads, as doR. autumnalis and R. fletcheri sp.nov., and is assigned here to the genus Rhysia as well.ETYMOL0GY: Rhysia fletcheri is named for Garry Fletcher, senior biologist at Pearson College and voluntary warden of the Ecological Reserve of Race Rocks, British Columbia, Canada, who was instrumental in establishing Race Rocks as an Ecological Reserve in 1980.

- Systematic account:

- FAMILY Rhysiidae Brinckmann, 1965

- GENUS Rhysia Brinckmann, 1965

- Rhysia fletcheri sp.nov

Material examined:

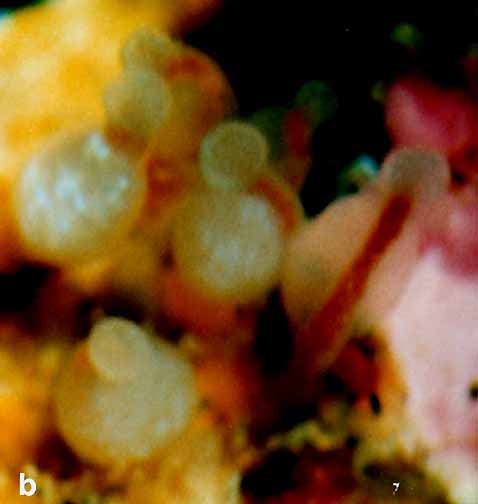

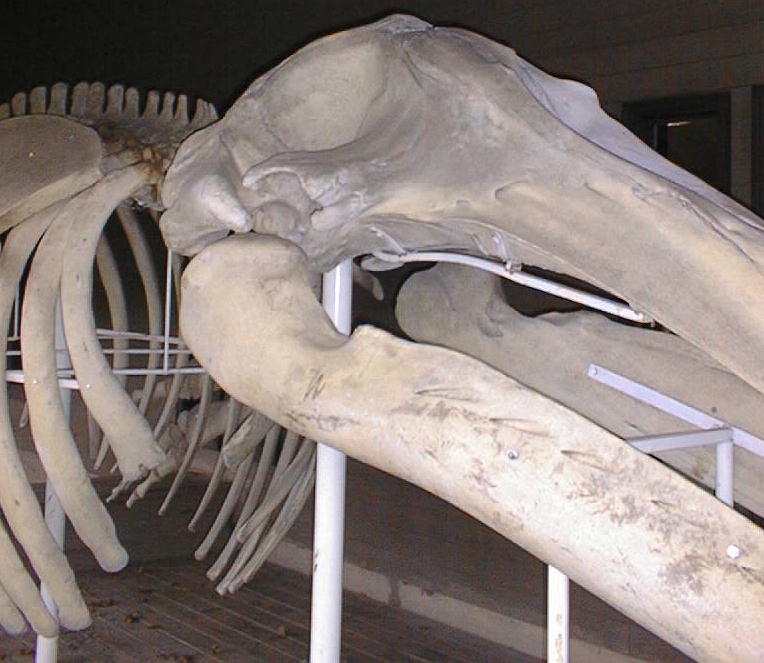

Growing on the valves of the barnacle Balanus nubilus , female and male colony .(.click on picture) . Top left, two females, below left gastrozooids: below right – male. Holotype: Friday Harbor, Washington, U.S.A., on Balanus nubilis attached to a tire on the side of floating docks at Friday Harbor Laboratories of the University of Washington, 0.5 m, 5 October 1984, female colony, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Cat. No. USNM 73984.

Paratypes: Race Rocks, British Columbia, Canada, on Semibalanus cariosus in tide pool, 0.5 m, 5 April 1990, male colony, Royal Ontario Museum Cat. No. ROMIZ B1164;

Friday Harbor, Washington, on hydrorhiza of a thecate hydroid colony, 10-15 m, October 1972, female colony,

Royal Ontario Museum Cat. No. ROMIZ B1165; Race Rocks, British Columbia, on Semibalanus cariosus in tide pool, 0.5 m, 15 June 1991, female and male colony, Royal British Columbia Museum Cat. No. RBCM 992-170-1.

Further material is deposited in the Natural History Museum, London, England.

Description:

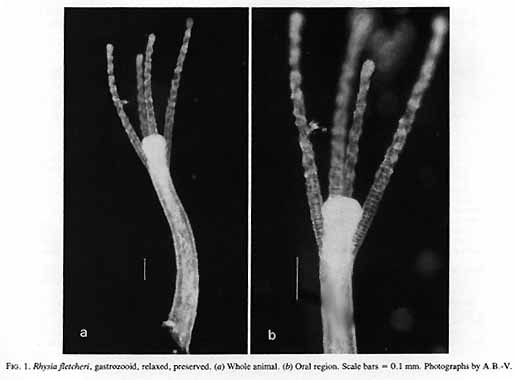

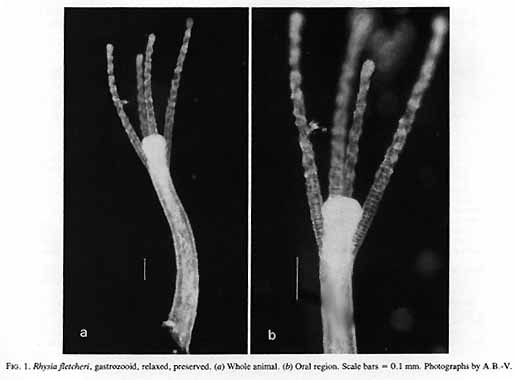

Hydroid colony stolonal, arising from a creeping and anastomosing hydrorhiza. Hydrorhiza thick (averaging 0.05 mm), covered with a very thin and often virtually invisible perisarc (Fig. 2a), giving rise to gastrozooids and gonozooids. Zooids inserting with hydrorhiza via a broad base and without a neck or stem (Figs. Ia, 2a); perisarcal collar absent around bases of zooids. Gastrozooids widely scattered, occurring singly or in a loose group. Gastrozooids extremely contractile, 0.3÷1.0 mm long, appearing columnar to barrel-shaped or like a contracted sea anemone if exposed to strong light (compare Figs. Ia and 4a).

(Page 402)

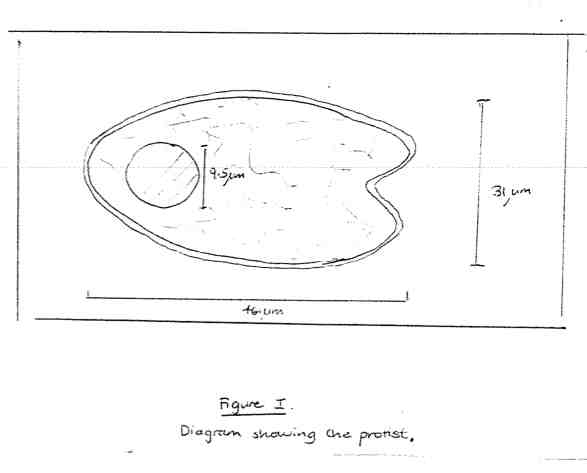

Figure 1. Rhysia fletcheri, gastrozooid, relaxed, preserved. (a) Whole animal, (b) oral region. Scale bars =0.1 mm. Gastrozocid tentacles 4 – 10, filiform, in a single whorl, 0.08 – 0.10 mm thick depending on the degree of contraction, each with more than 30 endodermal cells, cnidocysts arranged in a more or less distinct spiral (Fig. lb). Hypostome round, surrounded by a circle of 4 or 5 cnidocyst clusters that do not develop into tentacles (Figs. 2e, 2f, 4a). Gonozooids often separated from gastrozooids by several millimetres, occurring in dense clusters (Figs. 3, 4}. Gonads developing internally on one side of gonozooid, without a gonophore (Figs. 4b, 4c). Female gonozooids up to 1.1 mm high when mature (Figs. 3a÷3d); hypostome round, provided with a cap of cnidocysts, not divided into separate clusters as in gastrozooid; mouth lacking; tentacles typically lacking; in gastrozooid; mouth lacking; tentacles typically lacking; immature female gonozooids, at a stage not more than 115 the height of a mature gonozooid, being recognizable as such in showing an egg on one side. Male gonozooids develop 3 or 4 oral tentacles, which are shorter and thinner than those of gas- trozooids, each tentacle has up to 10 endodermal cells and bears cnidocysts at the tip only, some with thickened tips(Figs. 2c, 4b) because of the presence of larger numbers of cnidocysts (this varies among colonies); hypostome of males round, more conical than in females, provided with evenly distributed cnidocysts, unlike the cnidocyst clusters typical of gastrozooids; mouth lacking. Male gonozooids with mature gonads sometimes exceeding gastrozooids in length, reaching a maximum of 1.5 mm.

Dactylozooids absent.

Gastrozooids and gonozooids pink to orange, due to the colour of the endoderm; tentacles and hypostomes milky white; eggs and planulae peach coloured; male gonads milky white in early stages, iridescent in later stages.

Cnidocysts: large microbasic euryteles (average 10; 20.2/1 9.6 um) (height/diameter) when exploded; small microbasic euryteles (average 10; 9.6/4.8 um when exploded); desmonemes (not measured). Cnidocysts: large microbasic euryteles (average 10; 20.2/1 9.6 um) (height/diameter) when exploded; small microbasic euryteles (average 10; 9.6/4.8 um when exploded); desmonemes (not measured).

|

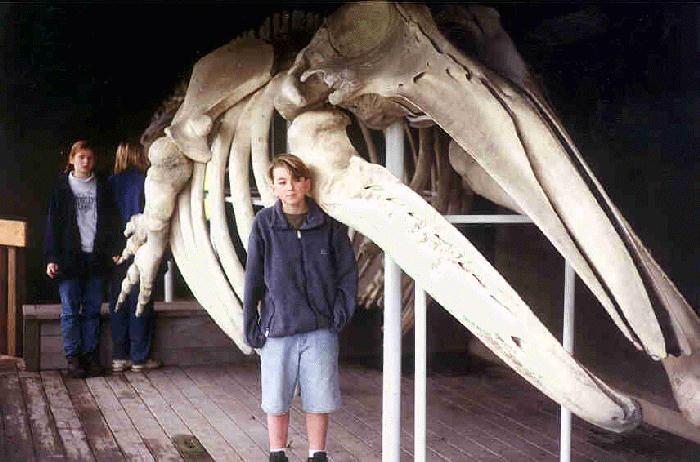

Included here are some of our archival photos of the various activities that students were involved in the CoastWatch Program

Included here are some of our archival photos of the various activities that students were involved in the CoastWatch Program

In the spring and fall terms, we have had programs with the grade seven classes from local schools in our Schools Program visiting for trips in the Race Passage area of Southern Vancouver Island.

In the spring and fall terms, we have had programs with the grade seven classes from local schools in our Schools Program visiting for trips in the Race Passage area of Southern Vancouver Island. The seafront at Lester Pearson College with the DUEN — taken from the air

The seafront at Lester Pearson College with the DUEN — taken from the air The Duen is no longer with the college but up to recent years Mike and Manon, seen here with Phillipe Cousteau operated Duen Sailing Adventures along the Coast of British Columbia and Haida Gwaii

The Duen is no longer with the college but up to recent years Mike and Manon, seen here with Phillipe Cousteau operated Duen Sailing Adventures along the Coast of British Columbia and Haida Gwaii