The Diving Service Schools Project 1999

Link to our 1997-98 season of the Diving Service Schools Project.

Link to our 1997-98 season of the Diving Service Schools Project.

| In the spring term, 1999, the students of the Diving Service took groups of grade 7 students from the Sooke school district on field trips to the Marine Protected Area of Race Rocks Ecological Reserve. | |||||||||||||||||

GOALS OF THE DIVING SERVICE SCHOOLS PROGRAM:

In order to make the experience more enjoyable and informative for everyone, we suggest that the students do some research before coming on the field lab. It would make things more interesting if they could get a basic familiarity with some of the possible species in the different phylums which they will be seeing at Race Rocks.

|

Color Polymorphism in the Intertidal Snail Littorina sitkana at Race Rocks

Patterns of Color Polymorphism in the Intertidal Snail Littorina sitkana in the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area.

- Figure 1 In Fig. 1 the snails were purposely placed on the white quartz substrate to show the contrast between a shell of color 27 ( white ) and some of colors 1 – 10 ( Black to grey ).

- Figure 2 The same process was repeated in Fig. 2 below only on black, basaltic substrate adjacent in the same tidepool. (Note three black snails (color 1-10) in lower left hand corner.)

- In Figure 3. Several colors of snail can be seen grazing on the golden diatoms in Pool 4 in the spring of 1998.

Extended Essay done by: Giovanni Rosso, Lester Pearson College, 1998 .

The complete version of the research is available in the Library at the college.

Abstract:

As with most intertidal gastropods, Littorina sitkana shows remarkable variations in shell color. This occurs both in microhabitats which are exposed or sheltered from wave action. There seemed to be a close link between the shell coloration of the periwinkle and the color of the background substrate. Field work was carried out on the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area in order to investigate patterns of color polymorphism. Evidence from previous studies was used to support interpretations and understand certain behaviors.

The results showed that in the study site there was a very strong relation between the shades of the shells and the colors of the rocks. Light colored shells stayed on light shaded rocks and vice versa. An interesting pattern was noticed with the white morphs. These were rare along the coast

(only 2%), but were present in relatively high numbers in tidepools of white quartz. From previous experience (Ron J.Etter,1988), these morphs seem to have developed as evolutionary response a higher resistance to physiological stress from drastic temperature changes between tides. Some results showed that the white morph is present in an unexpectedly high percentage at the juvenile stage, but then their number decreases dramatically. As in Etter’s study more research needs to be made on the role visual predators have in this phenomenon.

ROSSO, Giovanni Edoardo 0034 -083

Patterns of Color Polymorphism in the Intertidal Snail Littorina littorea at

the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area.

AN EXTENDED ESSAY PREPARED FOR THE INTERNATIONAL BACCALAUREATE

Candidate number: 0034 – 083 February 1999

Name: Rosso, Giovanni Edoardo

Best language: Italian

School: Lester B. Pearson College of the Pacific

Subject: Environmental Systems

Supervisor: Mr. Garry Fletcher

Table of contents:

Abstract ————————————————————— 3

Introduction ———————————————————- 4

Materials and methods ———————————————- 5

Data analysis ———————————————————- 7

Conclusion ———————————————————– 12

Observations ——————————————————— 13

Evaluation ———————————————————— 16

Suggestions for further studies ———————————— 16

Acknowledgments ——- ——————————————- 18

Literature cited —————————————————— 18

Appendix ————————————————————- 19

2

Abstract:

As most intertidal gastropods, the Littorina littorea shows remarkable variation in shell color. This occurs in both microhabitats that are exposed or sheltered from wave action. There appeared to be a close link between the shell coloration of the periwinkle and the color of the background surface. Fieldwork was carried out at the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area in order to investigate patterns of color polymorphism. Evidence from previous studies was also taken into account to better support interpretations and understand certain behaviors.

The results showed that in the study site there was a very strong relation between the color of the shells and the color of the rocks. Light colored shells lived on light shaded rocks and vice versa. An interesting pattern was noticed on the white morphs. These were rare along the coast (Only 2%), but were present in relatively high numbers in tidepools set in white quartz. From previous experience (Ron J Etter, 1988 ), these morphs seem to have developed, as an evolutionary response, a higher resistance to physiological stress from drastic temperature changes between tides. Some results showed that the white morph is present in an unexpectedly high percentage at the juvenile stage, but then their number decreases dramatically with age. As in Etter’s study, more research needs to be done on the role of visual predators in this phenomenon.

3

Introduction:

There is strong evidence to prove that intertidal gastropods are highly polymorphic for shell coloration (Ron J Etter, 1987). Even within a single species it is not uncommon to find considerable shell color variation in a single trait (Laurie Burham, 1988 ). In the genus Littorina the color of the shell often appears to be parallel to the one of the background (Heller, 1975; Smith, 1976; Reimehen, 1979; Hughes and Mather, 1986 ). Nevertheless the causes and patterns of color polymorphism. in intertidal gastropods are still a fairly unexplored field. Many paths have been undertaken to make some light upon these obscure areas. The most common interpretation was always the presence of visual predators (Ron J Etter, 1987) like birds and fish. Others investigated on the effects of the shells diets. But more recent studies ( Rowland, 1976; Ossborne, 1977; Berry, 1983 ; Etter, unpubl. ) have shown that diet virtually does not affect the shell coloration, although the intensity of pigmentation might be slightly altered. Finally, physiological stress has been introduced as a possible cause color polymorphism. A very interesting study, made by Ron J. Etter on the intertidal snail Nucella Lapillus, shows how the white coloration suffers much less from temperature variations in dry micro habitats as opposed to the brown morphs. With his work he gave some revolutionary insights on the distribution of the shells according to their color.

In my fieldwork I chose to disprove the null hypothesis that there is no link between the color of the periwinkle and the color of the substrate it is living on. In order to do this I sampled a great quantity of empty shells and scaled their color from I to 27. 1 then chose five rocky coastal areas, each of a different shade. I analyzed the color of the live shells on each of the chosen rocks, scaled them according to their color and then graphed the results. I also observed the young shells in the inside of barnacles and took notice of their color frequencies in relation to their quantity. I ended my study looking in some tide pools and recording new surprising results. I concluded that:

I roughly calculated that between one station and the other there was a change in tide level of 13 cm. I therefore kept this in account and lowered the quadrat accordingly into the water.

Data analysis-

Rock – 1 (Black)

The rock contained a creek were I noticed a very high density of periwinkles in a very limited area. In the inside of the creek they were almost piled and glued on top of each other. With the help of a pen I extracted them and laid them on a white sheet of paper. Once I accomplished the process of identification I put them back. I noticed that the bigger shells (10 to 14 mm wide) were located on top of the smaller ones (3 to 6 mm wide). This made me think that the bigger ones wanted to protect the smaller ones from swells and predators. It actually does work as a protection system, but it surely is not because of the kind nature of periwinkles. It is obviously a matter of physical size.

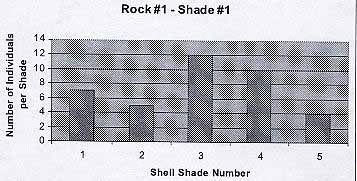

Rock #1 -Shade #1

From the graph we see that the black rock hosted the darkest shades, from 1 to 5. The average number of individuals per shade is 7.6. The average shell color is 3.

7

Rock # 2- Dark grey

As opposed to the previous case the surface of rock # 2 was rather flat. Population was regularly distributed. All shells seemed to be above 5 mm in width. Here I had the opportunity to understand the great resistance that periwinkles have to salinity changes. In fact some of the shells were located under the flow of a fresh water pipe. It might have been a coincidence but these shells were slightly bigger (7 to 12mm wide).

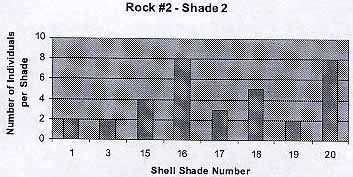

Rock #2 – Shade 2

The graph shows that there are some exceptions (Color 1, 3) to the trend that has been shown in the previous graph. I guessed that these are the cases of lucky shells that have not jet been seen by birds or fish. The average number of individuals per shade is 4.25 . The average shell color is 13.6 .

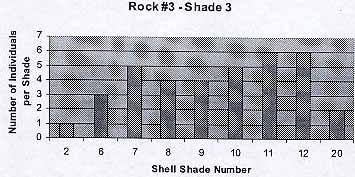

Rock – 3 (Brownish red)

The reddish color of the rock came from many small algae that covered its surface. I did not notice any irregular patterns in distribution. The shells seemed to be above 5 mm in width.

8

The background color was parallel to the shade of the periwinkles. Color 1 and 20 appear to be exceptions: only three individuals in total. The average number of individuals per shade is 4.4 . The average shell color is 9.4.

Rock – 4 (Light brown)

The surface of the rock was very irregular.. Some areas were covered with dead barnacles ( Balanus sp. ). I noticed that here the shells were smaller in size and they tended to be gathered around the barnacles. Nevertheless I repeated the process.

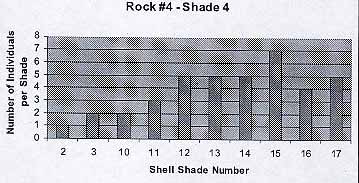

Rock #4 -Shade 4

9

The population reflects the previous trends. The average number of individuals per shade is 3.8. The average shell color is 11.3.

Rock – 5 (White rock with dark patches)

This rock was one of the most interesting ones. In fact, the two different shades of the rock gave place to a particular phenomenon that clearly disproved the null hypothesis. I tried to be as precise as I could in distinguishing the shells on the white and dark spots. I noticed the net distinction between the color polymorphism on the two areas.

Rock #5 -Shade 5

In the light patches the average number of individuals was 4.3. The average shell color was 23. In the dark areas the average number of individuals was 4.8. The average shell color was 3.

If the color of the shell would be directly proportional to the one of the rock, the average shell colors would be:

Ideal Model

10

Rock 1

| 3 | |

| Rock 2 | 13 |

| Rock 3 | 8 |

| Rock 4 | 18.5 |

| Rock 5 | 24.5 / 3 |

Actual Model

In the actual experiment the averages were:

Rock 1

| 7.6 | |

| Rock 2 | 13.6 |

| Rock 3 | 9.4 |

| Rock 4 | 11.3 |

| Rock 5 | 23 / 4.8 |

I assume that the dark grey rock is actually lighter than the brownish red

one. If we observe the results we understand that that:

| Rock Number Actual Shade |

Ideal One | Error | |

| 1 | 7.6 | 3 | 4.6 |

| 2 | 13.6 | 13 | 0.6 |

| 3 | 9.4 | 8 | 1.4 |

| 4 | 11.3 | 18.5 | 7.2 |

| 5 | 23 / 4.8 | 24.5 / 3 | 1 / 1.8 |

Considering that a minority of the shell color numbers was far away from the average: the average error is of 2.8. This means that on average the actual color was 2.8 units away from the ideal one, therefore disproving the null hypothesis. (Chi square test was used to verify the results.)

11

Conclusions:

The data analysis clearly shows that in the Race Rocks area there is a very strong relation between the color of the shell and the color of the background they are standing on. The shells with light shades are found on light colored rocks. The same relation is true also for the opposite extreme case were we find black shells on black rocks.

I feel that the model we can create from this experience is relevant above all because the consequences of human presence are reduced to very low levels. In fact, I have been operating in a Marine Protected Area were not many people go. The area is relatively free both from water and air pollution. The only predators are the natural ones. Besides this, the ecosystem is intact and the populations of all the organisms are at almost climax level. The amount of visual predators includes crabs, sea gulls, black oystercatchers, pigeon guillmonts, otters and fish.

From the observations made (p. 13, second part) on the entirely white morphs, we may deduce that there is a strong link between what Ron J. Etter found out on the Nucella lapillus and the Littorina littorea. Putting the pieces of the puzzle together we notice that the distribution of periwinkles is obviously affected by numerous reasons. There seems to be a wide color gap between the shades 1 to 26 and 27. The first twenty-six, when wet, are not very different from each other. The white morph instead is clearly identifiable both when it is wet or dry. If we keep in account that the vast majority of the coastal area on Race Rocks is dark, obviously it will be easier to for shells 1 to 26 hide. The white shells instead have such a great disadvantage that only 2% survive. Keeping in account Etter’s results we may conclude that, excluding a minority of extraordinary circumstances, all these deaths are caused by predators. In fact, when the juvenile periwinkles leave the barnacles, their shell is still soft. Now, if the white periwinkles are born near an area of white surface, then their chances of being seen decrease and actual groupings of white shells may be noticed. The color of their shell also allows them to bare physiological stress much better than the darker shades. The stress comes from the drastic changes in temperature between tide variations. In the case of the Nucella lapillus, in Etter’s experiment, the white shells inhabited most of the sheltered areas and, as previously mentioned, dry areas. This could also apply to the Littorina littorea, but on the Race Rocks Island the sheltered areas are very few and the number of predators is high. The white quartz is the only substrate that can host them (once they leave the Balanus sp.). I feel that if the ocean conditions were not as rough and there would be fewer

12

predators, the white morphs would also be seen on the darker rocks. In the tide pool both the white morph and the dark one live together The mortality of the last though is obviously higher, both for predation and stress (Ron J Etter).

In the dark areas the presence of the white morph is almost nonexistent (2%). But the shells belonging to shades 1 to 26 are distributed according to a remarkable pattern. On light colored rocks we will find shells that belong to the high numbers. In the opposite case the same trend applies. – In the area I took in exam this close relation is probably emphasized by the high intensity of predation. The contrasts are easily spotted and eliminated. Therefore, in the absence of predators, I think that the darker shells would be able to live on any color surface. Of course the dark population would suffer more in the dry areas as opposed to the lower levels.

Observations:

As I was watching the newborn shells (about 1 mm wide) in the dead barnacles I found out that the presence of white shells is unexpectedly high at this stage. I tried counting them and recording the results. On average a dead 20-mm wide Balanus sp. holds between four and eight shells of Littorina littorea. I analyzed ten samples in two different areas and recorded the number of white juvenile shells:

Area

| Total number of shells | Number of white shells | |

| 1 | 5 | 2 |

| 6 | 2 | |

| 8 | 4 | |

| 4 | 3 | |

| 4 | 1 | |

| 5 | 3 | |

| 6 | 4 | |

| 7 | 3 | |

| 6 | 2 | |

| 8 | 5 | |

| 2 | 4 | 2 |

| 7 | 4 | |

| 8 | 5 | |

| 3 | 0 | |

| 5 | 3 | |

| 7 | 4 | |

| 8 | 4 | |

| 6 | 3 | |

| 4 | 3 | |

| 9 | 5 |

In the first area the average Balanus sp. held 5.9 periwinkles and 2.9

were white or very light colored. The percentage of white shell was of 49.

In the second area the average Balanus sp. held 6.1 periwinkles and

3.3 were white. The percentage of white shells was of 54.

The results show that on average 51.5% of the shells are white. If we

make an exception for the tidepools, the percentage of white shells present

on the protected coastal areas is 2 (This is an approximate calculation made

when collecting the dead samples and when counting the live ones). This

means that 49.5% are eaten or die before reaching a sufficient size to move

in an area where they would be protected by the background they are

standing on. According to the study made by Ron J. Etter on the intertidal

snail, Nucella lapillus, when the brown morphs and the white ones were put

on the same exposed coastal area, there were virtually no differences in the

mortality rates of the two. If we dare to make a parallel between the two

species, it would be therefore wrong to assume that the white morphs die

because of natural causes such as diseases or disadaptation. It is my opinion

that literally 49.5% of the white morphs is victims of visual predators

because they can easily be seen before reaching an area where they would

camouflage. In this case, I am not including tide pools with white bottom

and where the water is shallow. I am referring to the morph with shade 27,

which is not common along the coast probably because of the lack of

almost entirely white rocks.

On the other hand I mentioned tied pools because of a specific reason. In

fact, on the Southwestern part of the island there are six tide pools, each

with different depths and different consequent bottom coloration. During

the days of the experiment this area was inaccessible for the presence of

about 75 California sea lions and about 23 Stellar. Nevertheless, in previous

visits to the island for other reasons (the reserve is in fact managed by

Pearson College and is used for several academic programs, projects and

environmentally oriented diving) I had the opportunity to observe the

presence in tide pool – 4 of about 20 entirely white shells of Littorina littorea

standing on white quartz. This had originated a question that had long

14

remained without an answer. Why can the white periwinkles be found only in this tide pool (if we exclude the two- percent I was talking about before)? The most common explanation was based on the presence of certain minerals, difficult predation and a genetic mutation that occurred only there. To be honest, after coming across Ron J. Etters study on the Nucella Lapillus, it was hard for me not to relate the two cases.. In his study he states that the white morph heats up at a lower rate as opposed to the brown morph in shallow and protected areas. Observing a higher rate of mortality (not due to predation) in the brown morph, he deduced that the white morph had developed a better defense mechanism against physiological stress. It therefore has higher chances of survival in very shallow water or in those areas that remain exposed between tides for a long time. Although brown snails can avoid exposure to the sun by moving to more shaded and moist microenvironments, Etter thinks their greater susceptibility to stress nonetheless puts them at a disadvantage by limiting their foraging area and increasing the amount of time that they must spend in hiding- This in turn could lead to slower growth rates and reduced levels of fecundity (Laurie Burnham, Scientific American, September 1988 ). On the other hand this does not exclude the presence of natural predators, especially in young age.

If we compare these results to the observations made on Race Rocks we may find many points in common. Especially after I had a new confirmation. In fact, in a tide pool with difficult access in another part of the island I found a similar behavior. On a small area of white quartz I found five entirely white periwinkles. There is a big difference in size between the ones I found there and the population of tide pool – 4. The first ones were about 2-3 mm wide; the second ones were 6-12mm. This might be due to the fact that they were living in a creek of difficult access to most predators. Nevertheless the pattern fits: the white periwinkles are almost all found in areas of shallow water or that remain exposed for a long time between the action of tides. On the other hand these are the only areas were white quartz is found on the island. The observations made on the fieldwork make me almost certain that the reasons for the white morphs to be in the tide pools are an adaptation to physiological stress and a perfect camouflage. In Etters experiment most of the protected areas were inhabited by white morphs. On Race Rocks only two tide pools contained such organisms and in very low quantities. I think this can be explained by the combination of several factors. In the first place the ocean conditions around the island are

15

very rough and they make it hard for the shells to survive in all areas.. In the second place there is very limited quantities of white rock were the shells can camouflage. Finally the very high quantity of visual predators, both from the air and form the sea, make it very difficult for these shells to move around because they will immediately be seen.

Evaluation:

Due to the lack of hi-tech material I had to verify my observations with simple tools- This forced me to use other people’s previous studies (Ron J. Etter) to better understand what I saw. If I had disposed of an instrument to measure the internal temperature of the shells I could have repeated Etters experiment on the Littorina littorea.

My experiments allow the creation of a model that is true, as far as we know, only on the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area. Other generalizations should be verified. In order to obtain a more reliable model the experiment should be repeated over a longer period of time on a regular basis. The month of October is a period when there is a significant increase in predation also due to the fact that the colony of seagulls on the island is incremented by the newborn.

I chose a vast scale of shade variations in order to achieve more precise results. By doing this, it was hard for me to identify exactly to which number each shell belonged. Even though I tried my best I might have made some mistakes.

Knowing that there are significant differences in distribution between the exposed and the sheltered areas, each of the sites was not exposed to the same environmental conditions. Some were more exposed to currents than others.

Suggestions for further studies:

As I mentioned in the introduction the causes and patterns of color polymorphism in intertidal gastropods are a fairly unexplored field. There are therefore still many grey areas that need to be cleared.

The fieldwork I had the opportunity to make on Race Rocks allowed me to learned many things on these fascinating creatures, but posed also many questions to which I have no answer.

I was surprised when I found so many white periwinkles in the barnacles. It would be interesting to find out exactly what happens to them once they leave these shells:

Who exactly are their predators?

16

At which stage in growth does their shell become too hard to be digested?

How do they choose the areas where they stop?

Are there certain types of minerals that create better conditions for living? Is there a link at all?

What is the exact probability for a shell to be white at birth?

Is the gene universal or is it majority- present in certain areas?

How does the alimentation affect growth and reproduction rate?

The white shells are more tolerant to physiological stress, but does this affect the immunitary system? Which diseases are the most common?

The fieldwork I have done seems to apply for Race Rocks, but is it true also in other nearby areas? To what extent does the exposure to rough environmental conditions affect distribution? Since the tide pool was covered and surrounded by sea lions, it was obviously affected by their waste products. The population of periwinkles seems to be fairly stable? How tolerant are these shells to changes in pH? Is there a difference between the degree of tolerance of the dark and the white morphs?

17

Acknowledgments

I sincerely thank my supervisor, Mr. Garry Fletcher, for his encouragement, support, precious advise and constructive criticism. I am also very grateful to Mr. Mike and Miss. Carol Slater for hosting me on the island during the field work. I will never forget the delicious supper we had together on Thanksgiving Day. In the end, I would like to thank Mr. Chris Blondeau for his sincere interest and for bringing me at Race Rocks by boat.

Literature cited:

Laurie Burnaham, September 1988, The hard shell, pp.26-27, Scientific American.

Ron J. Etter, April 1987, Physiological stress and color polymorphism in the

intertidal snail Nucella Lapillus, Museum of comparative zoology, Harvard

University, Cambrige, MA 02138.

Jane M. Hughes and Peter B. Mather, December 1984, Evidence for predation as a

factor in determining shell colorfrequencies in a Mangrove snail Littorina Sp.,

School ofAustralian Environmental Studies, Griffith University, Nathan,

Queensland,Australia.

18

APPENDIX 1. Photographs of Littorina littorea

In Fig. 1 the snails were purposely placed on the white quartz substrate to show the contrast

between a shell of color 27 (white) and some of colors

1 – 10 ( Black to grey).

The same process was repeated in Fig. 2 below only on black, basaltic substrate adjacent in the

same tidepool. (Note three black snails (color 1-10) in lower left hand corner.)

Figure 1 Figure 2

19

Apendix 2. Photographs of the shell shades of Littorina littorea

There was a very significant difference in color between the dry and the wet shells. In the two pictures some of the shells had to be moved around in order to maintain the darker periwinkles before the lighter ones. For example, wet shell number 11 had to be moved to 9 on the dry scale

20

Appendix 3. Picture from Ron J. Etters fieldwork

Ron J. Etter noticed that in the Nucella Lapillus the white morph was more common in the sheltered areas. The brown one dominated in the areas of wave exposure. He concluded that the color of sea shells on the seashore may be an evolutionary response to physiological stress.

The color of seashells on the seashore may be an evolutionary response to physiological stress

Photographs of Littorina sitkana Figure 1

Figure 1

In Fig. 1 the snails were purposely placed on the white quartz substrate to show the contrast between a shell of color 27 ( white ) and some of colors 1 – 10 ( Black to grey ).

The same process was repeated in Fig. 2 below only on black, basaltic substrate adjacent in the same tidepool. (Note three black snails (color 1-10) in lower left hand corner.)

In Figure 3. Several colors of snail can be seen grazing on the golden diatoms in Pool 4 in the spring of 1998.

In Figure 3. Several colors of snail can be seen grazing on the golden diatoms in Pool 4 in the spring of 1998.

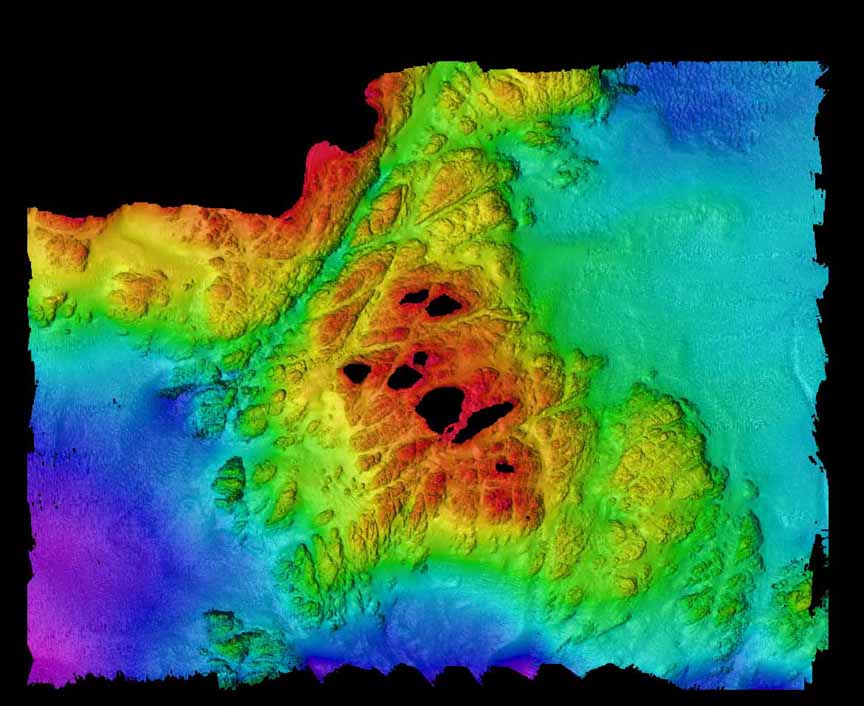

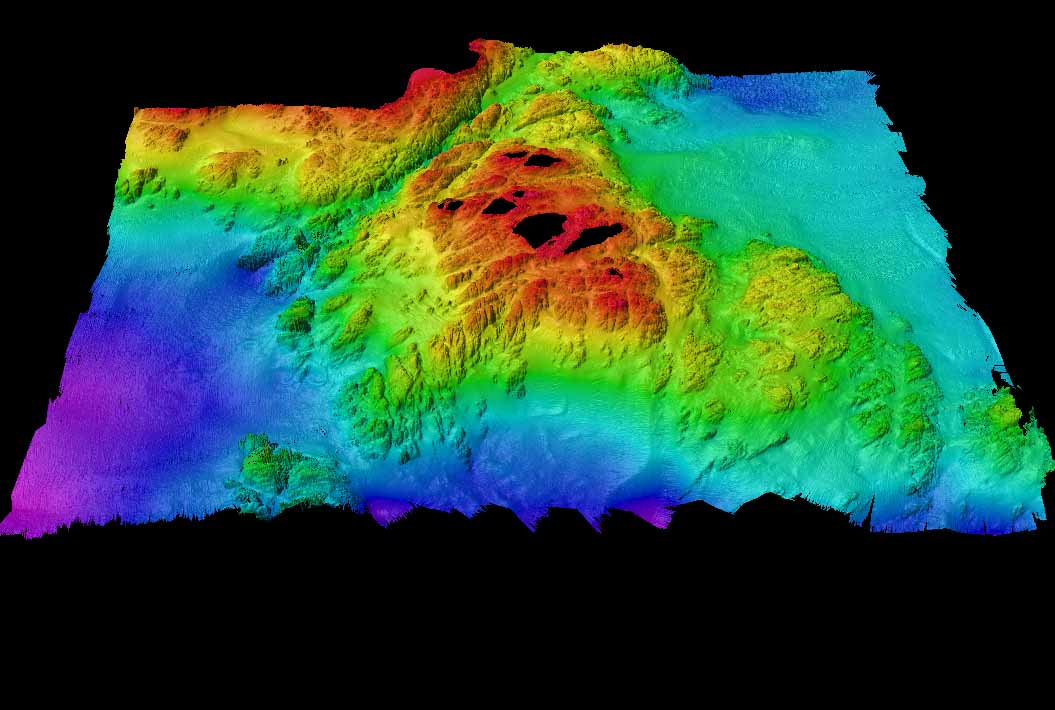

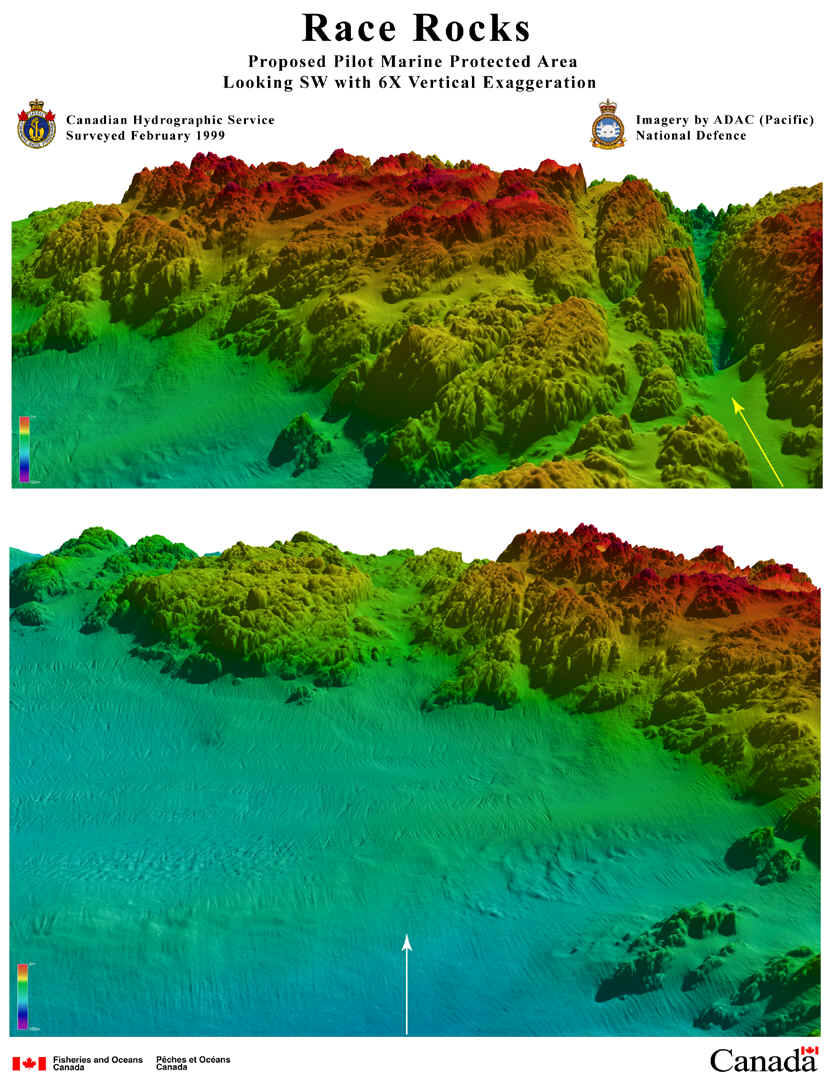

ACOUSTICAL BATHYMETRY OF RACE ROCKS

ACOUSTICAL BATHYMETRY OF RACE ROCKS

Pelican in reserve

Chris relief.

16:40 pelican seen on West side of a great race. 14:00 2 explosions on Bentinck island scared birds and sea lions off the rocks.

Wednesday – December 9,8:20 Pelikan observed on east side.

Abalone tagging at Race Rocks with Pearson College Divers

In 1998, we began a long term research program, initiated by Dr. Scott Wallace, on the population dynamics of the Northern Abalone

(Haliotis kamtschatkana). For several years, the Pearson College divers monitored the population. In this video, Pearson College graduate Jim Palardy (PC yr.25) explains the process.

Race Rocks Announced as One of Canada’s First Marine Protected Area Pilots Sept. 1, 1998

Canada became the first country in the world to adopt its own Oceans Act in 1997. In it there were constructive plans for the designation of Marine Protected Areas |

|

NEWS RELEASE: Race Rocks Announced as One of Canada’s

First Marine Protected Area Pilots Sept. 1, 1998 |

“Today at 1:30 pm. in Victoria, BC at a luncheon in the Empress Hotel in conjunction with the Coastal Zone Canada ‘ 98 Conference, The Honourable David Anderson , Minister of Fisheries and Oceans for Canada announced that Race Rocks and Gabriola Passage will become the first two Marine Protected Areas for the Pacific Coast of Canada. The minister emphasized that this was an historic occasion as it represents the first steps of many in creating these special areas for the conservation of marine resources. The two areas will serve as “Pilot MPA’s ” and represent the first of several areas to be designated in the three oceans of Canada. On hand for the announcement by the minister was Garry Fletcher, faculty member in biology and environmental systems at Lester Pearson College, along with many invited guests from the aboriginal communities, environmental groups, provincial government officials, and other stake holders in the marine environment of British Columbia.” (click on picture for the complete speech.) “Today at 1:30 pm. in Victoria, BC at a luncheon in the Empress Hotel in conjunction with the Coastal Zone Canada ‘ 98 Conference, The Honourable David Anderson , Minister of Fisheries and Oceans for Canada announced that Race Rocks and Gabriola Passage will become the first two Marine Protected Areas for the Pacific Coast of Canada. The minister emphasized that this was an historic occasion as it represents the first steps of many in creating these special areas for the conservation of marine resources. The two areas will serve as “Pilot MPA’s ” and represent the first of several areas to be designated in the three oceans of Canada. On hand for the announcement by the minister was Garry Fletcher, faculty member in biology and environmental systems at Lester Pearson College, along with many invited guests from the aboriginal communities, environmental groups, provincial government officials, and other stake holders in the marine environment of British Columbia.” (click on picture for the complete speech.)In the ensuing months, negotiations will take place with the ministry in order to set up the parameters of these new Marine Protected Area pilot study areas. |

| DFO BACKGROUNDER: RACE ROCKS – XwaYeN A Success Story for Community and Stakeholder Involvement- Sept 14 2000 |

In January of 1999, as part of the requirements of the Marine Protected Areas Pilot review process, Garry Fletcher was contracted by Fisheries and Oceans Canada to complete The Race Rocks Ecological Overview. An MS Access metadatabase of all the relevant Race Rocks ecological information was assembled . This database and accompanying references and audiovisual material are now available in the library at Lester B. Pearson College. In January of 1999, as part of the requirements of the Marine Protected Areas Pilot review process, Garry Fletcher was contracted by Fisheries and Oceans Canada to complete The Race Rocks Ecological Overview. An MS Access metadatabase of all the relevant Race Rocks ecological information was assembled . This database and accompanying references and audiovisual material are now available in the library at Lester B. Pearson College.

Go to the Proceedings of this workshop. Official designation of Race Rocks as Canadas first Marine Protected Area |

| RACE ROCKS ADVISORY BOARDIn this index , you will find a complete set of references to the proceedings of meetings of the advisory board, the proposal sent to Ottawa and the subsequent disappointing Gazetted version which alienated First Nations, leading to the final ratification of MPA satus being put on hold. |

Marine Protected Areas A Strategy for Canada’s Pacific Coast

Marine Protected Areas

A Strategy for Canada’s Pacific Coast

Marine protected areas are a vital part of our commitment to sustainable economies, viable coastal communities, and a healthy, diverse marine environment. Our goals are to protect and conserve the natural beauty and richness of our marine areas, to maintain ecological diversity, and to preserve the many recreational, natural and cultural features of our Pacific coastline for all time.

DISCUSSION PAPER August 1998

A Joint Initiative of the Governments of Canada and British Columbia

Foreword

On behalf of the governments of Canada and British Columbia we are pleased to present this discussion paper, “Marine Protected Areas, A Strategy for Canada’s Pacific Coast“. The Pacific coast of Canada is one of the most diverse and productive marine environments in the world – we rely on it in many ways, as a source of food,employment, recreation and spiritual renewal. We want to build and protect this richness for present and future generations. Our commitment to a Marine Protected Areas Strategy isa key piece of the foundation for this goal.

This Strategy has been developed jointly by federal and provincial agencies and clearly reflects the need for governments to work in unison to achieve common marine protectionand conservation goals. The Strategy is not a new program, but an initiative to coordinate all existing federal and provincial marine protected areas programs under a singleumbrella. This will allow for the development of a national system of marine protected areas on the Pacific coast by the year 2010 which is interlinked with the marine componentof the B.C. Protected Areas Strategy.

This discussion paper reflects extensive advice and feedback from our resource agency staff, as well as local governments, First Nations, and community, stakeholder andindustry perspectives. We now want to provide all marine interests and users an opportunity to review and comment further on the Strategy.

We are pleased that Canada and British Columbia are able to release this paper in 1998-the International Year of the Ocean. The success of conserving and protecting naturalmarine areas is a shared responsibility, we look forward to working with you to complete a “Marine Protected Areas Strategy for Canada’s Pacific Coast“.

Signed by Donna Petrachenko (Director-General, Pacific Region – Department of Fisheries and Oceans) Co-chair, MPA Strategy Steering Committee

Signed by Derek Thompson (Assistant Deputy Minister – British Columbia Land Use Coordination Office) Co-chair, MPA Strategy Steering Committee

Table of Contents

Foreword

1.0 Introduction

2.0 What are Marine Protected Areas

3.0 The Need to Create Marine Protected Areas

4.0 Vision and Objectives for a Marine Protected Areas Strategy

5.0 Developing a System of Marine Protected Areas

6.0 Your Feedback on the Strategy

Appendix A: Principal Participating Agencies in the Development of the Marine Protected AreasStrategy

Appendix B: Federal and Provincial Statutory Powers for Protecting Marine Areas

1.0 Introduction

The Pacific coast is host to a multitude of ecological, social, cultural and economic values which provide benefits and opportunities for all who have the good fortune to enjoyour spectacularly beautiful maritime coastline. Few people know that our coast is also among the most biologically productive in the world and continues to generate tremendouswealth for British Columbians and Canadians.

We have recognized that the sustainability of the world’s oceans is increasingly becoming a critical concern to coastal nations. The need to maintain the health andvitality of our marine resource base, together with broad ranging global issues such as continued urbanization of coastal areas, pollution, habitat alteration and loss, and overexploitation, are key concerns. These problems and opportunities are fueling our desire to establish a system of marine protected areas along the Pacific coast of Canada as oneessential tool to address the needs of our oceans.

The MPA Strategy proposes three important elements:

- A joint federal-provincial approach: All relevant federal and provincial agencies will work collaboratively to exercise their authorities to protect marine areas.

- Shared decision-making with the public: Commits government agencies to employ an inclusive, shared decision-making process with marine stakeholders, First Nations, coastal communities, and the public.

- Building a comprehensive system: Seeks to build an extensive system of protected areas by the year 2010 through a series of coastal planning processes.

The benefits of marine protected areas are many, and include:

- contributing to the protection of the structure, function and integrity of ecosystems;

- encouraging expansion of our knowledge and understanding of marine systems;

- enhancing non-consumptive and sustainable activities; and,

- improving the health of our ocean resources.

A total of 104 marine protected areas on the Pacific coast have already beenestablished. These were put into place using a variety of legislative tools and they consist predominantly of relatively small marine parks, ecological reserves and wildlifemanagement areas created to meet specific conservation and recreation needs. In the past, the need to work in collaboration to reach mutual goals was not apparent, and the majorityof protected areas were created by individual federal and provincial agencies operating on their own.

Central to this Strategy are a number of coastal planning processes which would be undertaken by governments over time throughout six major coastal regions (see Section5.2). These planning processes are inclusive and collaborative, in order to involve everyone with an active interest and to ensure that general and specific uses of coastaland marine areas, including Marine Protected Areas, are addressed.

For example, as part of the coordinated planning approach, Canada and B.C. signed an agreement in 1995 called the Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy (PMHL), which has as itscentral vision the creation of a system of marine and coastal protected areas along the entire Pacific coast. The current focus of the PMHL is the acquisition of land in thesouthern Gulf Islands and the consideration of a complementary Marine Conservation Area in the Gulf Islands’ encompassing waters.

To date, a federal-provincial government Working Group and senior management Steering Committee have been working to develop this Strategy discussion paper. However, broaderpublic involvement and acceptance is needed and will be essential to the success of the Strategy. This paper provides readers with an overview of the proposed Strategy andinvites comments. Section 6.0 in particular poses specific questions to which we are seeking your comments.

2.0 What are Marine Protected Areas

“Marine protected areas” are sites in tidal waters that enjoy some level of protection within their respective jurisdictions, although internationally the term may bedefined and interpreted quite differently from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. For example, the World Conservation Union uses it as a generic label for protected marine areas such assanctuaries, parks, reserves, harvest refugia and harvest replenishment areas. Under the new Canada Oceans Act, Fisheries and Oceans Canada has authority to formally designate Marine Protected Areas, however, in this discussion paper, we have agreed to usethe term broadly to describe all the federal and provincial designations that protect marine environments.

Sidebar #1: What are Marine Protected Areas

Marine Protected Areas could include:

-unique coastal inlets, bays or channels;

-representative marine areas;

-boat havens with important anchorages;

-marine-oriented wilderness areas;

-cultural heritage features;

-critical spawning locations and estuaries;

-species-specific harvesting refugia;

-foraging areas for seabird colonies;

-summer feeding and nursery grounds for whales;

-offshore sea mounts or hydrothermal seavents; and

-a host of other special marine environments and features.

Regardless of the particular designation, all marine protected areas (MPAs) under the Strategy would:

1. Be defined in law

The legal authority to establish an MPA will derive from one of several federal and provincial statutes including: Canada’s Oceans Act, Fisheries Act, National Parks Act, Canada Wildlife Act, Migratory Birds Convention Act, or proposed Marine Conservation Areas Act; and British Columbia’s Ecological Reserve Act, Park Act, Wildlife Act or Environment and Land Use Act.

2. Protect all or a portion of the elements within a particular marine environment

The federal and provincial governments have differing and, at times, overlapping jurisdiction in marine areas. Depending upon the statute under which an MPA is created,the area may comprise any combination of the overlying waters, the seabed and underlying subsoil, associated flora and fauna, and historical and cultural features.

3. Ensure Minimum Protection Standards

All MPAs would share Minimum Protection Standards prohibiting:

- ocean dumping;

- dredging; and,

- the exploration for, or development of, non-renewable resources.

Building on these minimum protection standards, the system of MPAs will accommodatemultiple levels of protection. Levels of protection provided by an MPA will vary depending upon the objectives for each site. For example, MPAs may be highly protected areas thatsustain species and habitats; areas that are established primarily for recreational use or cultural heritage protection; or multiple use areas that balance resource conservationwith recreational and other activities such as commercial and sport fishing. Even within a particular MPA, levels of protection may vary through the use of zoning specifyingpermissible activities for sub-areas.

Establishing a system of MPAs is only one part of an integrated approach to oceans management, but it is an essential one. MPAs help conserve the ocean’s life-givingservices, species and habitats to ensure that our coastal resources can continue to support present and future generations. The intent of MPAs is not to take anything away. Quite the opposite. MPAs can contribute to the restoration and conservation of marineresources for people whose livelihoods depend on harvesting. As well, they can support a wide range of recreational and aesthetic values, providing a win-win for all. Perhaps mostimportantly, they will help us to protect the quality of life we cherish. They are an insurance policy for our future.

Sidebar #2: Marine Protected Areas in a Global Context

The establishment of MPAs now occurs in many coastal nations around the world. While still less numerous than terrestrial protected areas, more than 1,300 MPAs have beencreated worldwide. MPAs have gained a high level of acceptance as a tool to help achieve the conservation of marine biodiversity, the sustainability of commercial and sportfisheries, and the viability of coastal communities that depend upon them.

Early efforts in the evolution of MPAs as a management tool took place mostly in tropical and sub-tropical waters-in the Florida Keys in 1935, in Australia’s Great BarrierReef in 1936, the Philippines in 1941, the Bahamas in 1958 and Mexico in 1960. Still today, most MPAs around the world have been established in these warmer marineenvironments, focusing on such important features as coral reefs, seagrass habitats and coastal mangroves. Temperate waters such as Canada’s have not been the subject of the samelevel of conservation efforts and the high levels of public awareness that, for example, the Great Barrier Reef generates.

B.C. has been the most active of Canadian provinces in the establishment of MPAs. The designation in 1925 of Glacier Bay National Park in Alaska may be the only MPA in theworld’s temperate waters to predate B.C.’s first marine parks at Montague Harbour and Rebecca Spit in 1957. Many of these early marine parks in B.C. were small, protectinganchorages and scenic shoreline areas important to recreational boaters. Beginning in the 1960s, and continuing through the 1970s and 1980s, however, the world began to recognizethe merits of MPAs as management tools for conservation, as well as for recreation, and called for the establishment of larger and more conservation-oriented MPAs. B.C. andCanada responded with the creation of new and larger areas such as Desolation Sound Provincial Park, Pacific Rim National Park Reserve (half of which is waters of the openPacific Ocean), and Checleset Bay Ecological Reserve.

Today, B.C. and Canada manage 104 MPAs, totaling about 1955 square kilometres. In addition, Canada is in the process of establishing the 3050 square kilometres Gwaii HaanasNational Marine Conservation Area in the southern Queen Charlotte Islands

3.0 The Need to Create Marine Protected Areas

The motivation to protect marine areas derives from a widespread appreciation of the beauty and bounty of the world’s oceans in the face of numerous pressures now affectingits health and stability. Largely a consequence of human activities, the serious stresses placed upon our oceans globally have given rise to calls for coastal nations to makeconservation and preservation of marine biodiversity and ecosystems a worldwide priority. This is the strongest message in the United Nations initiative to declare 1998 as theInternational Year of the Ocean.

3.1 Values of Canada’s Pacific Marine and Coastal Environments

With more than 29,500 kilometers of coastline, 6,500 islands and approximately 450,000 square kilometres of internal and offshore waters, the marine and coastal environments of Canada’s Pacific coast have an impressive variety of marine landforms, habitats and oceanographic phenomena that accommodate a broad range of species diversity. Island archipelagos, deep fjords, shallow mudflats, estuaries, kelp and eel grass beds, strong tidal currents and massive upwellings all contribute to an abundant and diverse assemblage of species.

The Pacific coast of Canada is one of the most spectacular and biologically productive marine and coastal environments of any temperate nation in the world. The northeastPacific represents a significant and varied collection of marine invertebrates comprised of more than 6,500 species. In the vertebrate family, there are 400 fish species, 161marine birds, 29 marine mammals, and one of the world’s largest populations of orcas; there are nesting grounds for 80 percent of the world’s population of Cassin’s auklet, and wintering grounds for 60 – 90 percent of the world’s Barrow’s goldeneye; as well, the region boasts of the world’s heaviest recorded sea star, and largest octopus, sea slug,chiton and barnacle.

Recognized as a spectacular and productive marine and coastal region, the northeast Pacific contributes significantly to B.C.’s economy and strongly influences the cultureand identity of its residents. It is estimated that the Pacific marine environment contributes up to $4 billion annually to the coast’s economy. In addition, one in everythree dollars spent on tourism in B.C. goes toward marine or marine-related activities.

B.C.’s marine regions also contain a rich cultural history. For the First Nations peoples who have lived along the shores for thousands of years, many coastal areas remainimportant for food, social, ceremonial, and spiritual purposes. The cultural history of the Pacific coast is further illustrated by numerous physical relics of the past, such asship wrecks and whaling stations.

As well, a vast array of recreational opportunities are available in coastal areas. For example, the Inside Passage is one of the most popular cruising and sailing destinationsglobally, and kayakers are attracted to the numerous archipelagos peppered along the coast. In a recent divers survey, British Columbia’s coast was rated as the best overalldestination in North America, even when compared to such tropical destinations as the Florida Keys, the Gulf of Mexico and southern California.

Some of these significant ecological, cultural, and recreational values are already protected in MPAs along the B.C. coast. Much of the current system has, however, beenestablished in an ad hoc manner with an emphasis on near-shore environments. The result is that many marine values and ecosystems remain underrepresented, and the levelsof protection both between and within protective designations vary significantly.

3.2 Threats to Marine Ecosystems

1. Physical alteration of critical habitat and marine areas

The alteration, deterioration or degradation of habitat has a significant impact on marine ecosystems. Habitats may be damaged through actions such as dredging and filling,trawling, anchoring, trampling and unauthorized visitation, noise pollution, siltation from land based activities, and altered freshwater inputs. Most habitat loss in B.C.occurs in estuaries and nearshore areas, but deeper areas can also be affected by ocean dumping. A primary concern in B.C. is the degradation and loss of eelgrass habitat, whichis important for numerous fish and shellfish species as part of their life cycles.

2. Excessive harvest of resources

History has clearly shown that the productive capacity of the seas and their ability to deliver resources to the needs of humankind are limited. In addition to the economic andsocial consequences of the excessive harvest of many fish and shellfish species, there are other ecological consequences. Recent research has suggested that around the world marineresource harvesting is altering the natural cycle of marine food webs. The continuation of this trend could result in serious implications for people who depend on the oceans’resources.

3. Pollution

While the water quality along Canada’s Pacific coast is generally considered to be quite good, there are many area specific concerns. These sources of pollution may includeindustrial and municipal wastewater discharges, agricultural runoff, the dumping of dredged materials, and the threat of oil and chemical spills. To date there has been nocoast-wide assessment of marine environmental quality, and no data exist on either the current status of or long term trends for water quality. One indicator of water quality -the number of shellfish closures – has risen along the B.C. coast to about 160 per year. This covers an area of approximately 100,000 hectares.

4. Foreign or exotic species of fishes and marine plants

The introduction of foreign or exotic marine species has altered the composition of many biological communities on the Pacific coast. Large areas of mudflat have beencolonized by an introduced eelgrass, rocky shorelines in the Strait of Georgia are often covered in introduced oysters, and one of the more common clams – the soft shell clam -has also been introduced. While some of these impacts occurred as far back as the turn of the century, others are still happening, such as the recent northward expansion of thegreen crab towards B.C.’s waters.

5. Global climate changes

Although the mechanisms driving long term climatic variations are complex, and the role of human activities in these changes has not been established, these fluctuations have alarge impact on the kinds and nature of species found in B.C.’s waters at any particular time. For example, during the past 1997/98 El Nino event, species usually found only inwarmer waters migrated northward into B.C.’s waters, where in many cases they consumed large numbers of local species.

4.0 Vision and Objectives for a Marine Protected Areas Strategy on Canada’s Pacific Coast

4.1 The MPA Vision

Generations from now Canada will be one of the world’s coastal nations that have turned the tide on the decline of its marine environments. Canada and British Columbia will haveput in place a comprehensive strategy for managing the Pacific coast to ensure a healthy marine environment and healthy economic future. A fundamental component of this strategywill be the creation of a system of marine protected areas on the Pacific coast of Canada by 2010. This system will provide for a healthy and productive marine environment whileembracing recreational values and areas of rich cultural heritage.

Along the coast of British Columbia, comprehensive coastal planning processes will be undertaken, ensuring ecological, social and economic sustainability. These processes willprovide the mechanism for establishing an MPA system and ensuring a holistic, inclusive and multi-use approach to resource use and marine management.

This is the vision behind the MPA Strategy, a future that can be realized through a cooperative and integrated process, and by a step-by-step commitment to the key objectivesoutlined below.

4.2 Objectives for Establishing Marine Protected Areas

MPAs will serve a range of functions and exist in a wide array of sizes, shapes, and designs. They are an important conservation tool that, when used in conjunction with othermanagement applications, can result in many benefits for coastal communities, tourists, and regional and national economies. Under this proposed Strategy, the establishment of asystem of MPAs would serve six objectives:

1. To Contribute to the Protection of Marine Biodiversity, Representative Ecosystems and Special Natural Features

MPAs can contribute to the maintenance of biodiversity at all levels of the ecosystem, as well as protect food web relationships and ecological processes. They give refuge tovulnerable species thus helping to maintain species presence, age, size distribution and abundance; they protect endangered or threatened species, preventing species loss; andthey preserve the natural composition and special natural features of the marine community.

Biodiversity is the variability among living organisms and the living complexes of which they are a part. It is expressed in the genetic variability within a species(such as different stocks of the same species), in the number of different species (e.g., 36 species of rockfish on the Pacific coast), and in the variety of ecosystems andhabitats along the coast (such as different plant and animal communities that appear with increasing water depth).

Representative ecosystems have been identified on Canada’s Pacific coast through the use of ecological classification systems. Parks Canada has identified Marine Regionsat the national level to plan the system of Marine Conservation Areas. At a more refined level, the B.C. government has identified 12 marine ecoregions with 65 sub-componentecounits. Both classification systems will help guide the planning of the system of MPAs to ensure it is highly representative of the diverse marine environments found on thiscoast.

Special natural features are elements of the environment that are rare, outstanding or unique. These areas may include stopover sites for certain migratingspecies, areas with rare and unique capabilities for maintaining early-life stages of important fish and shellfish species, and habitats of high biodiversity, such as estuariesor upwelling areas. While many of these elements may be captured within large, representative MPAs, it is also necessary to specifically identify and protect special,and often site-specific, features.

2. To Contribute to the Conservation and Protection of Fishery Resources and Their Habitats

Conserving and protecting fish stocks is critical for the sustainability and stability of many B.C. coastal communities. As a result, stakeholders are keenly interested in theimplications of MPAs for all fisheries, whether First Nations,, recreational, or commercial.

Studies of marine protected areas in temperate waters indicate that they can increase population size, increase average individual fish size, lead to the restoration of naturalspecies diversity, and increase population reproductive capacity. Studies also indicate that subsequent spillover benefits to harvested areas outside and adjacent to closed areasoften occurs.

MPAs can help maintain viable marine species populations and support the continuation of sustainable fisheries by:

- Providing harvest refugia

- Protecting habitats, especially those critical to lifecycle stages such as spawning, juvenile rearing and feeding

- Protecting spawning stocks and spawning stock biomass, thus enhancing reproductive capacity

- Protecting areas for species, habitat, and ecosystem restoration and recovery

- Enhancing local and regional fish stocks through increased recruitment and spillover of adults and juveniles into adjacent areas

- Assisting in conservation-based fisheries management regimes

- Providing opportunities for scientific research

3. To Contribute to the Protection of Cultural Heritage Resources and EncourageUnderstanding and Appreciation

Cultural resources are works of human origin, places that provide evidence of human activity or occupation, or areas with spiritual or cultural value. Some examples arearchaeological sites, shipwrecks, or cultural landscapes. Terrestrial cultural resources have traditionally had more meaning than marine cultural resources because they tend to bemore evident and observable. Yet thousands of years of human occupation, including original First Nations cultures and early European contact and settlement are representedin the marine environment. MPAs can protect this rich cultural marine heritage and preserve First Nations traditional use and practices.

4. To Provide Opportunities for Recreation and Tourism

MPAs can support marine and coastal outdoor recreation and tourism, as well as the pursuit of activities of a spiritual or aesthetic nature. The protection of specialrecreation features, such as boat havens, safe anchorages, beaches and marine travel routes, as well as the provision of activities such as kayaking, SCUBA diving, and marinemammal watching will help to secure the wealth and range of recreational and tourism opportunities available along the coast.

5. To Provide Scientific Research Opportunities and Support the Sharing of Traditional Knowledge

Scientific knowledge of the marine environment lags significantly behind that for the terrestrial environment which can affect the ability of marine managers to identify themerits of protection or management options. MPAs provide increased opportunities for scientific research on topics such as species population dynamics, ecology and marineecosystem structure and function, as well as provide opportunities for sharing traditional knowledge.

6. To Enhance Efforts for Increased Education and Awareness

Over the last few years, public understanding and awareness of marine environmental values and issues have been increasing. There is general recognition that proactivemeasures are necessary to protect and conserve marine areas to sustain their resources for present and future generations. However, there is still a significant need for publiceducation to instill greater awareness of the role everyone can play in the conservation of marine environments. Many MPAs will afford unique opportunities for public educationbecause of their accessibility and potential to clearly demonstrate marine ecological principles and values.

5.0 Developing a System of Marine Protected Areas

Sidebar #3: Guiding Principles for MPA Development

1. Working With People

The federal and provincial governments will work in partnership with First Nations, coastal communities, marine stakeholders and the public on MPA identification,establishment and management.

2. Respecting First Nations and the Treaty Process

Canada and B.C. consider First Nations’ support and participation in the MPA Strategy as important and necessary. Both governments will ensure and respect the continued use ofMPAs by First Nations for food, social and ceremonial purposes and other traditional practices subject to conservation requirements. Therefore, MPAs will not automaticallypreclude access or activities critical to the livelihood or culture of First Nations. The establishment of any MPA will not preclude options for settlement of treaties, and willaddress opportunities for First Nations to benefit from MPAs.

3. Fostering Ecosystem-Based Management

An ecosystem-based approach to management requires that the integrity of the natural ecosystem and its key components, structure and functions are upheld. This meansmaintaining natural species diversity and protecting critical habitats for all stages in species life cycles.

4. Learning-By-Doing

A key aspect of Canada and B.C.’s commitment to establishing MPAs is the concept of using a learn-by-doing approach. Both governments recognize that the process for MPAplanning should evolve and improve over time given the variations between coastal regions, the dynamics of a marine environment, and the information constraints concerning marinespecies, processes and ecosystems. Flexibility and adaptability will be required to meet effectively and efficiently the needs of all marine resource users.

5. Taking a Precautionary Approach

Taking a precautionary approach means, “When in doubt, be cautious.” This principle puts the burden of proof on any individual, organization or government agencyconducting activities that may cause damage to the marine ecosystem.

6. Managing for Sustainability

The MPA Strategy is intended to contribute to sustainability in our marine environments. This means that resources in areas requiring protection must be cared for inthe present so that they exist for future generations. In the marine environment, emphasis will be placed on maintaining viable populations of all species and on conservingecosystem functions and processes.

5.1 The Coastal Planning Framework

It is proposed that a network of MPAs would be developed through coastal planning processes carried out at a number of different levels. These may range from comprehensiveprocesses that plan for a wide variety of resource uses and activities, to processes which focus on planning for very specific purposes or for the resolution of defined issues.Regardless of the level of planning for MPAs, public participation will be a fundamental component of all processes, with the principles of openness and inclusiveness forming thebasis.

This approach would enable the collaboration of all governments, including First Nations, as well as stakeholders, advocacy groups, communities and individuals in theidentification of important marine values and areas that warrant consideration for MPA status. We are seeking a commitment from everyone who has an interest to work together toestablish a system of MPAs for Canada’s Pacific coast.

The coastal planning processes are to be collaborative planning efforts, consistent with both the federal objectives for Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) andprovincial objectives for coastal zone planning.

The establishment of a complete MPA system on the coast would be largely dependent on the rate at which planning processes occur, but a basic system is intended to be in placeby the year 2010.

5.2 Planning Regions for Marine Protected Areas

For the purposes of establishing an MPA system, six planning regions have been identified, reflecting the variety of oceanographic conditions, coastal physiography,management issues, and communities along Canada’s Pacific Coast (illustrated in Sidebar #4):

1. The North Coast

2. The Queen Charlotte Islands

3. The Central Coast

4. The West Coast of Vancouver Island

5. The Strait of Georgia

6. The Offshore

A coastal planning process is already underway for the Central Coast region. The Strait of Georgia region has also been identified as a priority for such processes, and a numberof initiatives are currently being undertaken or planned, such as the Georgia Basin Ecosystem Initiative and a Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy commitment to assess thefeasibility of establishing a Marine Conservation Area in the southern Strait of Georgia.

Sidebar #4: Proposed Marine Protected Area Planning Regions and Pilot Sites for Canada’s Pacific Coast

5.3 Federal-Provincial Coordination for Marine Protected Areas Establishment

To date a federal-provincial government Working Group and senior management Steering Committee have been working together to develop the MPA Strategy. To build on theseexisting working relationships and to solidify our commitment to federal – provincial collaboration we are proposing to ensure a coordinated approach to implementing the MPAStrategy via the establishment of an inter-governmental coordinating body.

This coordinating body would 1) provide policy, program advice, and interpretation to stakeholders and the public involved with MPAs and coastal planning processes, 2) overseepublic communications on program and policy issues, and 3) manage a joint, central system for tracking and monitoring the MPA program. It would support existing planning processeswhen required, and develop a standard analytical process to guide all MPA assessment work to ensure a consistent approach and achievement of the Strategy’s objectives. In areaswhere planning is not anticipated in the short term, this body would ensure a coordinated approach to the identification and assessment of candidate MPAs, and review requests forthe application of interim management guidelines for MPA candidates. Subject to public endorsement of this body, a specific Terms of Reference would be developed.

Sidebar #5: Interim Management Guidelines

Interim management guidelines may be applied to MPA candidates under exceptional circumstances where it has been demonstrated that they are necessary to protect specificmarine resources, habitats or values that may be under threat until coastal planning is completed. Any interim management guidelines instated would remain in place until MPAestablishment decisions have been made. Governments have various measures available for providing interim protection of marine resources and habitats, such as regulations underthe Fisheries Act and the deferment of granting tenures, permits or other rights to occupy or utilize certain sites. In addition, on an emergency basis, an MPA can beimmediately declared under the Oceans Act for a maximum-but renewable-period of 90 days.

Requests for the application of interim management guidelines may originate from the MPA proponent in areas where planning is not anticipated for the short term, or from thecoastal planning process participants in planned areas. Such requests would be reviewed by both levels of government for decision-making.

5.4 MPA Identification, Assessment and Recommendation

Step1: The Identification of MPA Candidates

The first step in establishing a system of MPAs would be to identify candidate areas that reflect important or key marine values, attributes or features. MPA candidates may benominated and presented to the technical teams supporting each planning process within their associated time-frames. Planning process participants would normally includegovernment agencies, First Nations, marine stakeholders, community groups, academic institutions or individuals.

Step 2: Assessment of MPA Candidates

Candidates would be assessed according to the objectives of the MPA Strategy. Criteria for the assessment, as listed in Sidebar #6, have been assembled from the federal andprovincial agency programs for protecting marine areas. The standards to be met would reflect the intended purpose of the MPA candidate as well as unique characteristics thatmight distinguish it.

Candidate MPAs would be considered within the context of all marine resource uses and activities along the coast and in the offshore. Participants in coastal planning processeswould review the results of MPA assessments and conduct any further research necessary-such as feasibility or socio-economic impact studies-in order to make theirrecommendations.

For example, in the coastal planning process now underway in the Central Coast, a multi-agency technical team will be receiving MPA candidate proposals from processparticipants, area residents, and from interested stakeholders directly. These candidates will then be assessed by the team according to MPA objectives and criteria and then byplanning participants in the context of other resource values and uses, MPA criteria, and environmental, social and economic objectives.

Step 3: Recommendations for MPA Designation

Recommendations for MPAs would be developed on the basis that the chosen candidates are both consistent with the objectives of the MPA Strategy and complementary to the range ofother coastal and marine uses and activities being considered under an existing planning process.

In areas where a comprehensive planning process is not underway, MPAs may be assessed and recommended through the application of a tailored MPA planning process. This approachwould be limited in use and applied only in certain situations, such as where there are pressing federal or provincial priorities or major gaps in the MPA network. Consistentwith the MPA Strategy Guiding Principles, public participation will be a fundamental component of both comprehensive and tailored planning processes, employing the principlesof inclusive, shared decision making.

Step 4: Decision-Making for MPAs

Recommendations would be reviewed by governments for decision-making. It may be necessary to undertake subsequent analyses or additional studies or approve therecommendations and proceed with the establishment of the MPA.

Legal designation formalizes the management authority, the geographic boundaries for the marine protected areas, and a broad description of acceptable or permissible uses. Insome cases, a marine protected area may have deliberately overlapping federal and provincial designations, depending on its location and the level of protection required.

Step 5: Management Plans for MPAs

The agency supporting the designation of a MPA would be responsible for developing and implementing a management plan. The management plan – consistent with the approvedplanning process recommendations – would clearly define the purpose of the marine protected area; its goals and objectives, and how the goals and objectives are to bereached. similarly, the management plan will provide the detailed terms and conditions around “where” “what” and “when” permissible uses can occur.

Management plans will be subject to periodic review. Reviewing the management plan for existing MPAs would provide an important opportunity to periodically assess theeffectiveness of the management regime in place, and to revise protection levels accordingly.

5.5 Pilot Marine Protected Areas

Adhering to the learn-by-doing principle, several pilot MPAs have been identified to test and explore a number of applications including: partnering and cooperative managementopportunities and mechanisms; criteria for evaluating proposed MPAs; and coordination among agencies or governments involved in the development of the MPA Strategy.

Areas that have been proposed as pilot MPAs include Gabriola Passage, Race Rocks Ecological Reserve (which is already formally designated as an Ecological Reserve), theBowie Seamount and the Endeavour Segment Hydrothermal Sea Vents. (see Map)

For several of these sites, stakeholder consultation is underway. Gabriola Passage has been subject to detailed study and consultation, but a few outstanding issues have yet tobe resolved. First Nations involvement will be considered very important to moving forward in this area. For Race Rocks Ecological Reserve, consultation is already underway througha management planning process.

Criteria used in selecting these areas as pilot projects included the following:

- level of existing stakeholder and/or community support;

- ecological, recreational and/or cultural heritage value;

- information availability;

- potential for building education and awareness; and,

- opportunities for research and monitoring.

The primary goal for pilot projects is to provide an opportunity to learn and testdifferent applications of MPA identification, assessment, legal designation, and management. Upon completion and evaluation of the pilots, formal designation may or maynot occur depending on the desire of local communities and First Nations, as well as stakeholders and the public. Throughout the MPA piloting process, opportunities will beprovided for public review and input.

In addition to these proposed pilot MPAs, both governments will be acting on their commitment in the Pacific Marine Heritage Legacy to study the feasibility of establishinga marine conservation area in the southern Strait of Georgia.

5.6 A Question of Targets – How Much is Enough?

There are varying views on the need for targets. As our knowledge of the marine realm greatly lags behind our knowledge of terrestrial environments, there is a need todetermine if MPA targets are appropriate, and if they are, then what they should be. There have been several attempts at designing measures to assess MPA targets both in B.C. and inother parts of the world, which include:

- targeting a set number of MPAs per planning region;

- targeting a percentage of area in each planning region;

- setting a target of a minimum of one relatively large “representative” MPA for each planning region (for example Parks Canada has used this approach for Marine Conservation Areas);

- targeting MPAs to protect representative areas of each habitat, ecosystem, or community type (B.C. has used this model for its terrestrial Protected Areas Strategy);

- using the best available science to determine protection requirements; and,

- not setting firm standards and limits for what needs to be protected and how much protection is required

We are seeking your advice on this important question.

5.7 Federal and Provincial Statutory Powers to Protect Marine Areas

Extensive legislative authorities already exist among the federal and provincial agencies to implement a comprehensive system of MPAs. These tools complement each otherand represent the various sources of constitutional and legislative powers necessary to enable us to work together to achieve the objectives of the MPA Strategy.

This federal-provincial partnership is essential since jurisdictional responsibilities in the marine environment are shared. For example, in all internal waters, the seabed isunder provincial jurisdiction, whereas in offshore areas it is under federal care. Throughout the marine environment, the organisms in the water column are under federaljurisdiction. However, the management of certain resources, such as aquaculture and the commercial harvest of oysters and kelp, is under the purview of the provincial government.Keeping this in mind, in some circumstances dual designation of an MPA using both federal and provincial legislative authorities may be required. For instance, some provincialparks and ecological reserves may need the added protection provided by an MPA under the Oceans Act to achieve their management objectives.

The various federal and provincial statutes and their designations for protecting marine areas are outlined in Appendix B. These consist of:

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Marine Protected Areas under the Oceans Act

- Fisheries Closures under the Fisheries Act

Environment Canada

- National Wildlife Areas and Marine Wildlife Areas under the Canada Wildlife Act

- Migratory Bird Sanctuaries under the Migratory Birds Convention Act

Parks Canada

- National Parks under the National Parks Act

- National Marine Conservation Areas under the proposed Marine Conservation Areas Act

British Columbia Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks

- Ecological Reserves under the Ecological Reserve Act

- Provincial Parks under the Park Act

- Wildlife Management Areas under the Wildlife Act

- Protected Areas under the Environment and Land Use Act

Sidebar #6 demonstrates how these designations relate and may be combined to achievespecific management objectives, and lists what criteria may be used to select the most appropriate designation(s) in each case.

Sidebar #6: Federal and Provincial Marine Protection Designations

MPA Protection Objectives Potential Protective Determining Criteria

Designation(s)

To contribute to the Oceans Act MPAs -representativeness

protection of marine Marine Conservation Areas -degree of naturalness

biodiversity, representative Marine Wildlife Areas -areas of high biodiversity

ecosystems and special Provincial Parks or

natural features. Ecological Reserves biological

Wildlife Management Areas productivity

(e.g. upwelling National Wildlife Areas -rare and endangered

environments, eelgrass beds, Migratory Bird Sanctuaries species

and soft coral communities.) -unique natural phenomena

-ecological viability

-vulnerability

-unique habitat

To contribute to the Oceans Act MPAs -areas of high biodiversity

protection and conservation Ecological Reserves and/or biological

of fishery resources and Marine Conservation Areas productivity

their habitats. Provincial Parks -rare and endangered

species

(e.g. spawning, rearing and -vulnerability

nursery areas.) -areas supporting unique or

rare marine habitats

-areas supporting

-significant spawning

concentrations or

densities

-areas important for the

viability of populations

and genetic stocks

-areas supporting critical