Race Rocks (XwaYeN)

Proposed Marine Protected Area Ecosystem Overview and Assessment Report

Executive Summary

Background

Race Rocks (XwaYeN), located 17 km southwest of Victoria in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, consists of nine islets, including the large main island, Great Race. Named for its strong tidal currents and rocky reefs, the waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) are a showcase for Pacific marine life. This marine life is the result of oceanographic conditions, supplying the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) area with a generous stream of nutrients and high levels of dissolved oxygen. These factors contribute to the creation of an ecosystem of high biodiversity and biological productivity.

In 1980, the province of British Columbia, under the authority of the provincial Ecological Reserves Act, established the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve. This provided protection of the terrestrial natural and cultural heritage values (nine islets) and of the ocean seabed (to the 20 fathoms/36.6 metre contour line). Ocean dumping, dredging and the extraction of non-renewable resources are not permitted within the boundaries of the Ecological Reserve. However, the Ecological Reserve cannot provide for the conservation and protection of the water column or for the living resources inhabiting the coastal waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as these resources are under the jurisdiction of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO).

The federal government, through the authority of the Oceans Act (1997), has established an Oceans Strategy, which is based on the principles of sustainable development, integrated management and the precautionary approach. Part II of the Oceans Act also provides authority for the development of tools necessary to carry out the Oceans Strategy, tools such as the establishment of Marine Protected Areas. This federal authority will complement the previously established protection afforded the area by the Ecological Reserve, by affording protection and conservation measures to the living marine resources.

Under Section 35 of the Oceans Act, the Governor in Council is authorized to designate, by regulation, Marine Protected Areas (MPA) for any of the following reasons:

the conservation and protection of commercial and non-commercial fishery resources, including marine mammals and their habitats;

the conservation and protection of endangered or threatened species and their habitats;

the conservation and protection of unique habitats;

the conservation and protection of marine areas of high biodiversity or biological productivity; and

the conservation and protection of any other marine resource or habitat as is necessary to fulfill the mandate of the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans.

In 1998, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans announced Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as one of four pilot Marine Protected Area (MPA) initiatives on Canada’s Pacific Coast. Race Rocks (XwaYeN) meets the criteria set out in paragraphs 35(1) (a), (b) and (d) above. Establishing a MPA within the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) area will provide for a more comprehensive level of conservation and protection for the ecosystem than can be achieved by an Ecological Reserve on its own. Designating a MPA within the area encompassing the Ecological Reserve will facilitate the integration of conservation, protection and management initiatives under the respective authorities of the two governments.

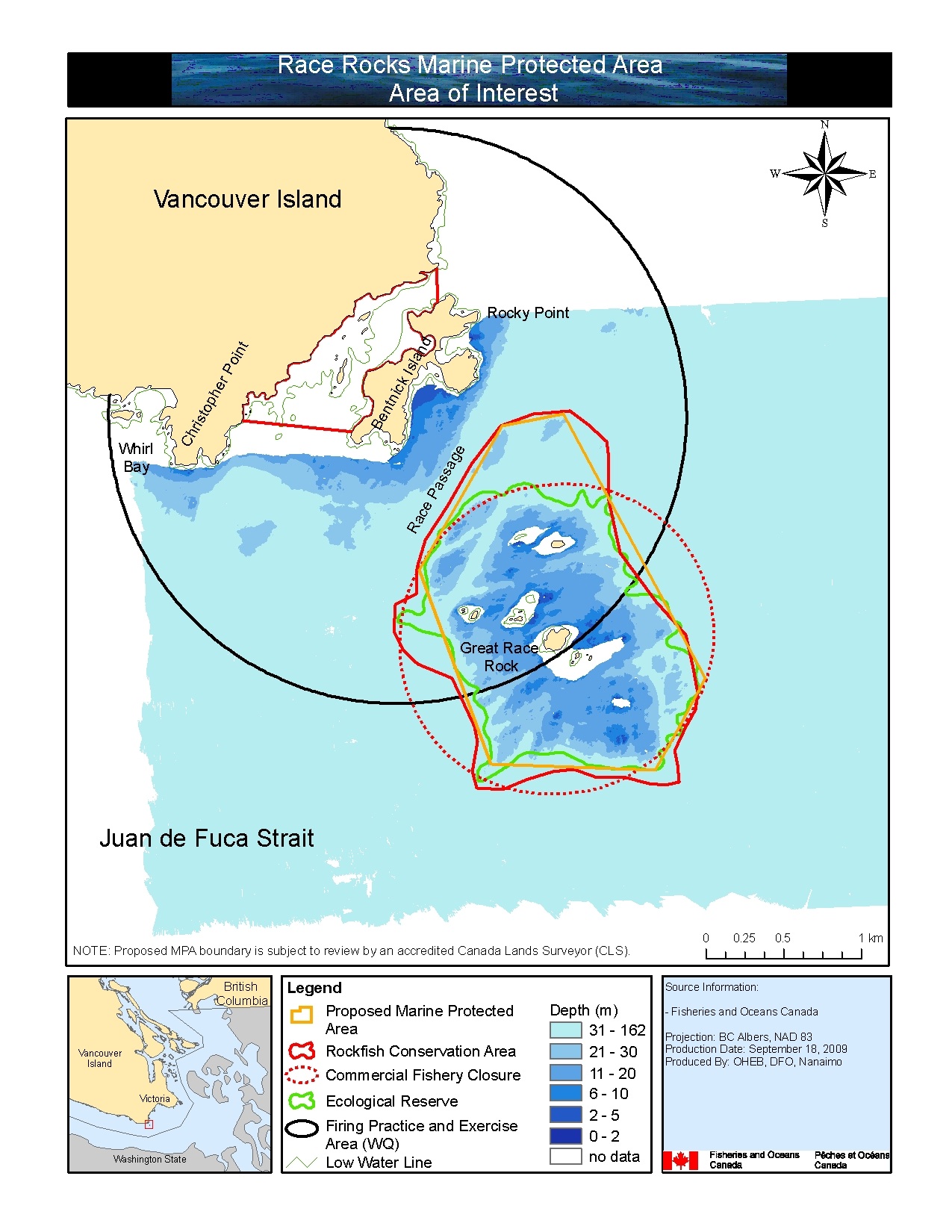

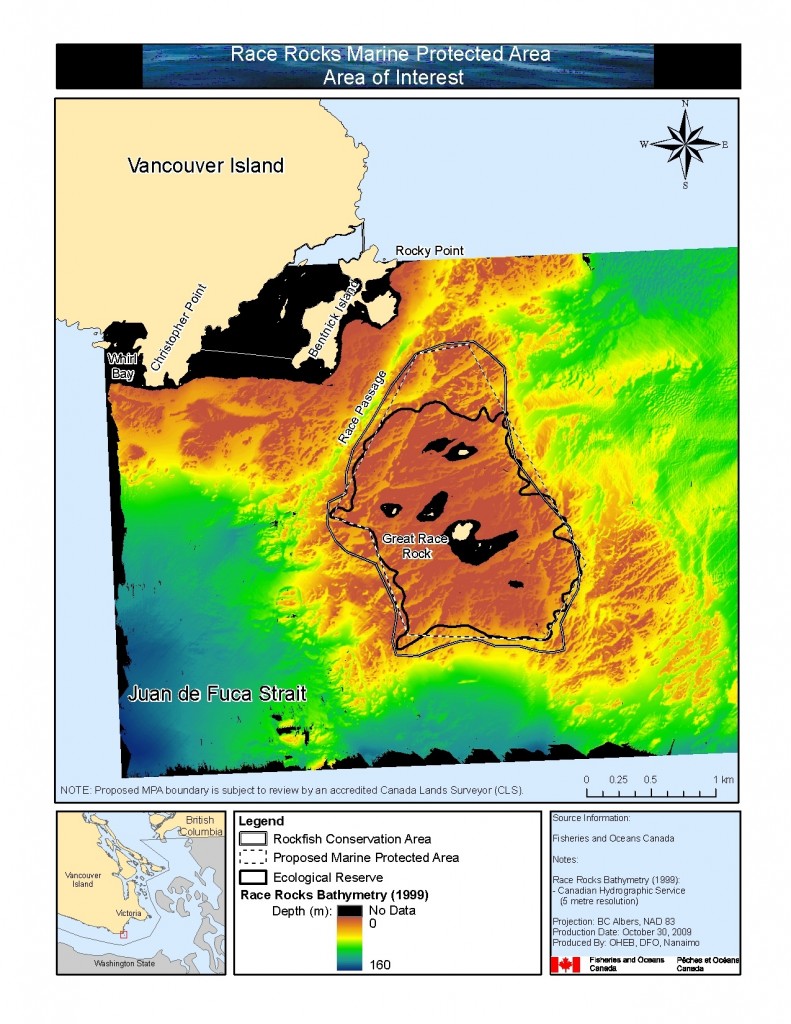

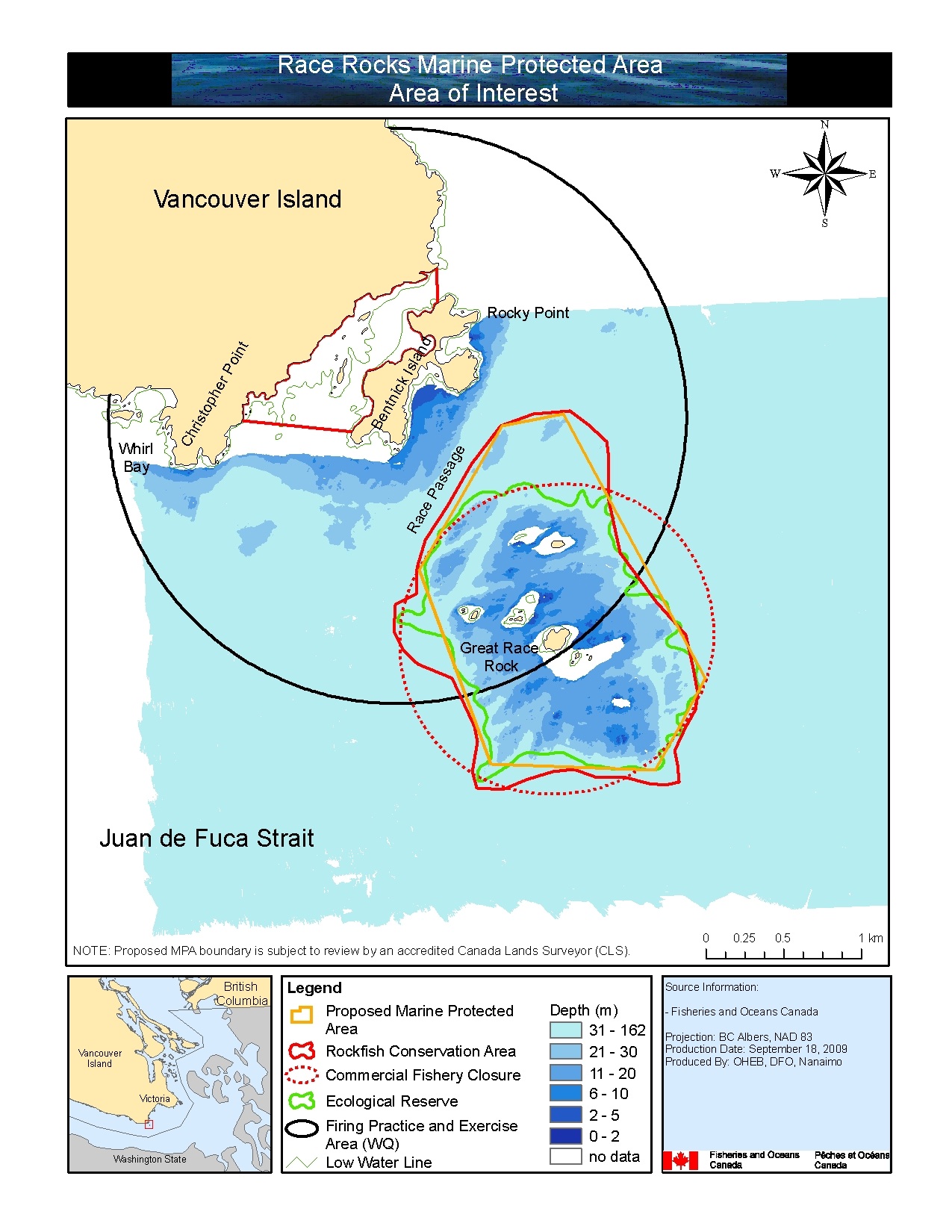

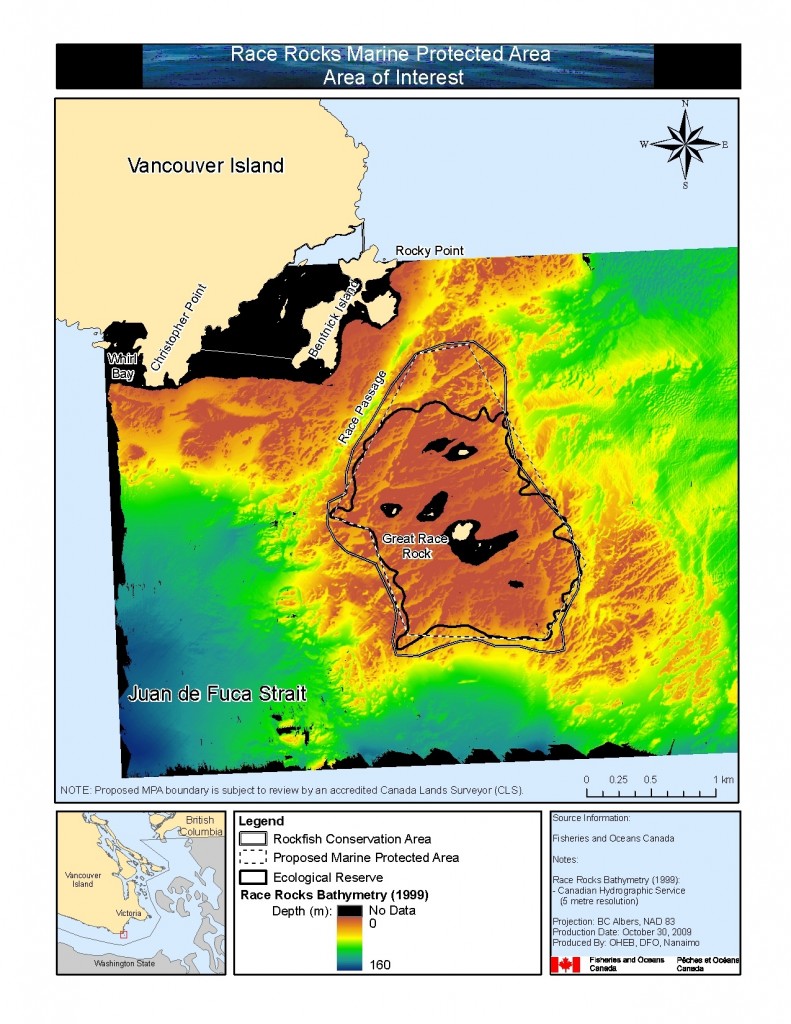

The Race Rocks (XwaYeN) proposed Marine Protected Area (MPA) is 268.5 hectares in size and encompasses the majority of seamounts surrounding Great Race, the largest of the islets (Figure 1). It is important to note that the selection of Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as a proposed MPA preceded the current framework for selecting Areas of Interest (AOI), which requires areas to be identifed as either ecologically and biologically significant areas (EBSA), or areas that contain ecologically significant species (ESS). Though Race Rocks (XwaYeN) was not identified through an EBSA or ESS process, the area does provide habitat to ecologically significant species (e.g. Northern abalone, Stellar sea lions) and would likely qualify as an EBSA due to the oceanographic and bathymetric (Figure 2) features and conditions. In future, proposed Marine Protected Areas, now referred to as Areas of Interest (AOI), will be selected through Integrated Management initiatives that employ EBSA and ESS identification methods.

Figure 1: Race Rocks (XwaYeN) proposed Marine Protected Area with boundary coordinates.

Figure 1: Race Rocks (XwaYeN) proposed Marine Protected Area with boundary coordinates.

Figure 2: Bathymetry surrounding the proposed Race Rocks (XwaYeN) Marine Protected Area.

Additional protection measures have been put in place in and around the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) area since 1990, including fisheries closures under the Fisheries Act and restricting all commercial fishing of finfish and shellfish in the area. Recreational harvesting of salmon and halibut and harvesting of non-commercial species continue, but much of that activity was curtailed after the designation of a Rockfish Conservation Area (RCA) around Race Rocks (XwaYeN) in 2004. The prohibition of living marine resource harvesting linked to an Oceans Act MPA designation will provide a longer-term commitment to the conservation and protection of the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) ecosystem.

In 2001, a comprehensive assessment of the physical and biological systems of Race Rocks (XwaYeN) was completed by Wright and Pringle (2001). The 2001 report provides an extensive ecological overview describing the geological, physical oceanographic and biological components of Race Rocks (XwaYeN) and the surrounding waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca at the time. Natural history observations and some traditional knowledge were also included. The following report is a brief update to summarize new information that has been collected in the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) area since that time and describe any changes to trends in species distributions and oceanographic conditions. This work is meant to supplement the existing ecological overview (Wright and Pringle 2001).

Ecological Overview of the Area of Interest

Physical Oceanographic Conditions

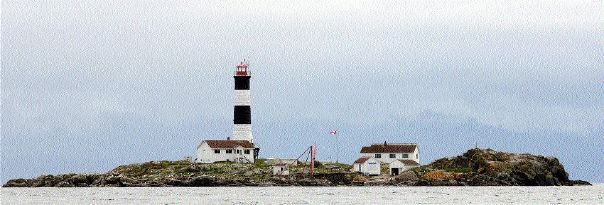

The Race Rocks (XwaYeN) lighthouse, located on Great Race Island, has recorded daily oceanographic and atmospheric conditions in the Strait of Juan de Fuca for several decades. The lighthouse was initially operated by the Canadian Coast Guard between 1860 and 1997, at which time the lighthouse became automated and Pearson College took over as the custodian. Race Rocks (XwaYeN), while located in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, is influenced by the conditions of the Strait of Georgia, particularly the waters flowing from the Fraser River. Freshets from the Fraser River generally result in warmer surface temperatures (warmer waters) and lower surface salinity (Wright and Pringle 2001).

Since 1921, sea surface temperature (SST) has been recorded daily. Wright and Pringle (2001) describe average monthly SST from 1921-1998. Figure 3 compares the average monthly SST (sea surface temperature) from Wright and Pringle (2001) with the average monthly SST over the last eleven years (1999 – 2009). Error bars representing a 95 percent confidence interval have been included for the 1921 – 1998 time series to determine if the average SST temperature over the last eleven years falls within the previously observed range.

Figure 3: Annual cycle of SST at Race Rocks comparing the historic trend with data from the past eleven years.

For most months, with the exception of the late summer and early fall (August, September, October) the average monthly temperatures for the past eleven years have been within the 95 percent confidence interval of previous observations. All monthly averages within the past eleven years have been slightly higher than the historic time series. The months of August, September and October were significantly warmer over the past eleven years than the historic time series. In general, surface temperatures at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) are coolest in the winter months and begin to increase with increased solar exposure due to longer days in the spring and summer.

Salinity data are monitored at the lighthouse and have been since 1936. Wright and Pringle (2001) describe average monthly SST from 1936 -1998. Figure 4 compares the average monthly salinity from Wright and Pringle (2001) with the average monthly salinity over the last eleven years (1999 – 2009). Error bars representing a 95 percent confidence interval have been included for the 1936 – 1998 time series to determine if the average salinity temperature over the last eleven years falls within the previously observed range.

Figure 4: Annual cycle of salinity at Race Rocks comparing the historic trend with data from the past eleven years.

Salinity measurements illustrate two distinct pulses of freshwater into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Changes in salinity in the Strait of Georgia are related to the freshwater output of the Fraser River. With the onset of the spring freshet from the Fraser River, the Strait of Georgia becomes weakly stratified with a surface freshwater lens (Wright and Pringle 2001). The result is a decrease in salinity values from May to July, with a peak discharge of the Fraser River in June. There is a second pulse of decreased salinity in the fall due to runoff from coastal watershed from seasonal precipitation from October to February. Average monthly salinity measurements from the past eleven years are not significantly different from historic monthly salinity measurements.

Biological Systems

The waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) are home to a thriving community of intertidal and subtidal invertebrates, fish, undulating kelp forests as well as many marine mammals such as whales, sea lions, seals and marine birds.

Updates on Plankton

Annual plankton surveys are conducted at fixed stations from the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the north end of the Strait of Georgia. However, there is no fixed station at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) nor has there ever been any targeted monitoring for plankton specifically at Race Rocks (XwaYeN). The objective of the annual surveys at the fixed stations is to provide an indication of plankton abundance. Since 1999, observations have been conducted four times a year (April, June, September, and December). Survey timing intentionally corresponds to different discharge levels of the Fraser River. Results from these surveys provide information on nitrate and phytoplankton concentrations, including assemblage composition of phytoplankton based on phytoplankton pigments in the water column. As presented in the 2009 State of Pacific Canadian marine ecosystems report (Crawford and Irvine 2009), the distribution of phytoplankton and nitrate concentrations in the upper 15 metres of the water column in the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Strait of Georgia, have been relatively consistent from 2002 to 2008. However, in the spring of 2008, phytoplankton and nitrate concentrations appeared lower in the southern Strait of Georgia in close proximity to Race Rocks while in the fall of 2008, phytoplankton concentrations were significantly higher and nitrate concentrations lower in the Strait of Juan de Fuca when compared with previous years (Crawford and Irvine 2009).

A comprehensive list of phytoplankton and zooplankton species observed in the Strait of Juan de Fuca can be found in Appendix 2 and 3 of Wright and Pringle (2001). Further discussion on the environmental conditions that influence plankton production can be reviewed in Wright and Pringle (2001).

Updates on Invertebrates and Marine Fish

Wright and Pringle (2001) summarized known information on benthic invertebrate communities at various intertidal and subtidal depths as well as the species composition of marine fish found in the waters of the proposed Race Rocks (XwaYeN) MPA. Since the writing of the ecological overview by Wright and Pringle (2001), studies on the Northern Abalone (Haliotis kamtschatkana), have continued and are further discussed in this report. Although not previously included in Wright and Pringle (2001), volunteer divers for the Reef Environmental Education Foundation documented occurrences of fish and invertebrate species that are known to exist in the south coast of BC. The REEF program and its findings from the waters surrounding Race Rocks are discussed below.

Race Rocks (XwaYeN) provides habitat to a wide variety of invertebrates including the Northern Abalone (Haliotis kamtschatkana), which was listed as Threatened under SARA in 2003. The Northern Abalone prefers intertidal or subtidal habitat on exposed and semi-exposed rocky shorelines at depths less than 10 m. Abalone surveys in 2005 along the southeast side of Vancouver Island, recorded a density of 0.0098 abalone/m2 for all sites surveyed. More detailed data exists pertaining to the location and results of this survey, but is confidential due to concerns for abalone conservation (i.e. not divulging known locations of abalone populations). This density estimate was drastically lower than estimates from two previous surveys on the southeast side of Vancouver Island that found 0.73 abalone/m2 in 1982 and 1.15 abalone/m2 in 1985, respectively (Adkins 1996). Similar surveys conducted in the San Juan Islands by the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife determined that the mean density at index sites was 0.04 abalone/m2 and ranged from 0.082 to 0.000 abalone/m2, including two sites where abalone were extirpated (Rothaus et al. 2008). Abalone stock in this area have declined by more than 98% since the mid-1980s (COSEWIC 2009).

In close proximity to Race Rocks (XwaYeN) is the William Head Penitentiary. Due to access restrictions enforced by a prison, the waters around William Head have resulted in a de facto marine reserve since 1958 (Wallace 1999). Timed surveys at the prison site found 0.77 abalone/min in 1996/97 and <0.1 abalone/min in 2005 suggesting that the abalone population around William Head is also disappearing (COSEWIC 2009). However, density transects were not completed at this site. While the cause of this population decrease may be the result of poaching, this is likely not the case due to the prison’s access restrictions. For this particular location, the most likely reason is simply that the large abalone found during the previous surveys have died and little or no recruitment has taken place (COSEWIC 2009).

Overall, the decline in Northern Abalone populations in the study area appear despite favorable oceanic conditions for abalone recruitment and an abundance of suitable habitat. While low recruitment and poaching have been identified as limiting factors to their recovery (COSEWIC 2009), population declines in this south coast area are believed to be solely due to recruitment failure and likely not due to poaching (J. Lessard pers.comm.). Overall, there is no evidence of population recovery in British Columbia since the fishery closed in 1990 (COSEWIC 2009).

The Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) coordinates dive surveys of fish and invertebrates following the Roving Diver Technique (RDT), a non-point visual survey method used by volunteer divers. Three REEF dive sites exist within the proposed Race Rocks (XwaYeN) MPA boundary: Great Race Rocks, West Race Wall and Rocks, and Rosedale Rocks. Volunteers are trained and examined on fish and invertebrate identification and assigned a designation of “novice” or “expert” as a result of their level of training and test scores. During a dive, volunteers record species observed as well as their abundance category, which is then used to determine a density index. REEF provides guidance and caution as to how to interpret their data. It is noted that the density index should only be used for guidance as the area is not rigorously controlled in the RDT method (REEF 2009).

Since 2001 (total bottom time of 12.5 hours), REEF survey results from Race Rocks (XwaYeN) have included 31 invertebrate species and 19 different species of fish. Table 1 provides a comparison of density and frequency of sightings for the three dive sites at Race Rocks (XwaYeN). Observed species are ranked according to total frequency of sightings across all three sites. The most frequently observed invertebrates were plumose anemone (Metridium senile), red and green urchins (Strongylocentrotus franciscanus and S. droebachiensis), sunflower star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) and pink hydrocorals (Stylaster verrilli). The most frequently observed fish were Kelp Greenling (Hexagrammos decagrammus), Lingcod (Ophiodon elongates), Copper Rockfish (Sebastes caurinus), Black Rockfish (Sebastes melanops) and Scalyhead Sculpin (Artedius harringtoni). REEF data will be of continued importance for its ability to track new occurrences of species at a specific location. These include China Rockfish (Sebastes neblosus), Kelp Greenling (Hexagrammos decagrammus), Longfin Sculpin (Jordania zonope), and Painted Greenling (Oxylebius pictus). An incentive for volunteer divers communicated by REEF includes the potential for ‘expert’ designated volunteer divers to become part of more rigorous research projects conducted in their area. Researchers noting interesting trends in REEF data may develop survey methodologies and solicit help from the volunteer divers to conduct the surveys necessary. This incentive could potentially be employed for research and/or monitoring purposes.

Updates on Marine Mammals

Race Rocks (XwaYeN) is a popular haulout site for pinnipeds in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Haulouts are a critical component to the life histories of pinnipeds making them important areas for bearing young, molting and resting. Five species of pinnipeds have been observed at Race Rocks (XwaYeN): Northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris), harbour seal (Phoca vitulina), northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus), Steller sea lion (Eumetopias jubatus) and California sea lion (Zalophus californianus).

Harbour seals are the most abundant marine mammal at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) with a non-migratory population present year-round. Race Rocks (XwaYeN) has the highest concentration of harbour seals on the Canadian side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Populations grew at an annual rate of about 11.5 percent (95 percent confidence interval of 10.9 to 12.6 percent) during the 1970s and 1980s, but the growth rate began to slow in the mid-1990s and the population now appears to have stabilized (Olesiuk 2008). The population estimate for harbour seals in the Strait of Georgia in 2008 was 39,100 (95 percent confidence interval of 33,200 to 45,000) (Olesiuk 2008).

Elephant seals occasionally migrate into the waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as their most northerly recorded haulout and have been noted to use the site as a haulout for moulting. Elephant seals normally breed in Baja (Mexico) or California, however, in January 2009 the first elephant seal pup was born on Great Race (REF???).

California sea lions, subadult and adult males, use Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as a winter haulout site between September and May. Abundance of California sea lions off southern Vancouver �Table 1: Comparison of fish and invertebrate sightings at three dive sites within the marine component of the Race Rocks Area of Interest between 2001 & 2009. SF% is a measure of how frequently a species was observed and indicates the percentage of time out of all the surveys that the species was observed. DEN is an average measure of how many individuals were observed based on a scale of 1-4.

Rank

Common Name

Scientific Name

Total

Great Race Rock

West Race Wall & Rocks

Rosedale Rocks

���SF%�DEN�SF%�DEN�SF%�DEN�SF%�DEN��1�Kelp Greenling�Hexagrammos decagrammus�85.7�2.7�71.4�2.6�90�2.9�100�2.3��2�Red Sea Urchin�Strongylocentrotus franciscanus�85�3.7�83.3�3.4�80�3.9�100�3.8��3�Plumose Anemone�Metridium senile/Metridium farcimen�80�3.8�83.3�3.8�70�3.9�100�3.5��4�Sunflower Star�Pycnopodia helianthoides�75�2.1�83.3�2�60�2.2�100�2��5�Green Sea Urchin�Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis�75�3.1�83.3�3�80�3.3�50�2.5��6�Pink Hydrocoral�Stylaster verrilli/S. venustus�75�1.1�50�1�80�1.1�100�1��7�Lingcod�Ophiodon elongatus�71.4�1.8�42.9�2�80�1.8�100�1.8��8�Giant Barnacle�Balanus nubilus�70�3.9�50�3.3�70�4�100�4��9�Gumboot Chiton�Cryptochiton stelleri�70�2.8�66.7�3�60�2.8�100�2.5��10�Copper Rockfish�Sebastes caurinus�66.7�1.8�42.9�2�90�1.8�50�1.5��11�Orange Cup Coral�Balanophyllia elegans�60�3.9�33.3�4�80�3.9�50�4��12�Black Rockfish�Sebastes melanops�57.1�1.8�28.6�1�70�1.9�75�2��13�Orange Social Ascidian�Metandrocarpa taylori/dura�55�1�50�1�60�1�50�1��14�Scalyhead Sculpin�Artedius harringtoni�52.4�2.5�42.9�2.3�60�2.5�50�2.5��15�Cabezon�Scorpaenichthys marmoratus�47.6�1.3�57.1�1.3�40�1.3�50�1.5��16�Leafy Hornmouth�Ceratastoma foliatum�45�2.3�33.3�2.5�40�2.5�75�2��17�Rock Scallop�Crassedoma giganteum�45�2.4�33.3�2.5�50�2.2�50�3��18�California Sea Cucumber�Parastichopus californicus�40�2.5�16.7�1�50�2.8�50�2.5��19�Orange Sea Cucumber�Cucumaria miniata�40�2.8�50�3�30�2.7�50�2.5��20�Leather Star�Dermasterias imbricata�40�1.8�33.3�1.5�40�1.8�50�2��21�Quillback Rockfish�Sebastes maliger�38.1�1.9�42.9�2�30�1.7�50�2��22�Juvenile (YOY) Rockfish – Unidentified�Sebastes sp.�38.1�2.4�42.9�2�30�2.3�50�3��23�Oregon Triton�Fusitriton oregonensis�35�2.7�16.7�3�40�2.8�50�2.5��24�Coonstripe Shrimp�Pandalus danae/P. gurneyi�35�1.9�50�2�30�2�25�1��25�Fish-eating Anemone�Urticina piscivora�25�2.6�33.3�3�30�2.3����26�Shiny Orange Sea Squirt�Cnemidocarpa finmarkiensis�25�2.2���20�2�75�2.3��27�Fringed Tube Worm�Dodecaceria fewkesi�25�0.8���40�0.8�25�1��28�Longfin Sculpin�Jordania zonope�23.8�2.2�14.3�2�30�2.3�25�2��29�Opalescent Nudibranch�Hermissenda crassicornis�20�2���10�4�75�1.3��30�Northern Abalone�Haliotis kamtschatkana�20�1.3�33.3�1.5�20�1����31�Spiny Pink Star�Pisaster brevispinus�20�1.8�16.7�1�20�2�25�2��32�Red Irish Lord�Hemilepidotus hemilepidotus�19�1.5���20�1.5�50�1.5��33�Strawberry Anemone�Corynactis californica�15�1�33.3�1�10�1����34�Giant Pacific Octopus�Octopus dofleini�15�1.7�16.7�1�10�2�25�2��35�Yellow Margin Dorid�Cadlina luteomarginata�15�1.7�16.7�2�20�1.5����36�White-spotted Anemone�Urticina lofotensis�15�3.7�16.7�3�10�4�25�4��37�Wolf-Eel�Anarrhichthys ocellatus�14.3�1.7�28.6�1.5�10�2����38�Painted Greenling�Oxylebius pictus�14.3�2�28.6�2�10�2����39�Puget Sound Rockfish�Sebastes emphaeus�14.3�2.3�14.3�2�20�2.5����40�Candy Stripe Shrimp�Lebbeus grandimanus�10�1.5���10�2�25�1��41�Northern Feather Duster Worm �Eudistylia vancouveri�10�1���20�1����42�Moon Jelly�Aurelia aurita/labiata�10�1.5���20�1.5����43�Longfin Gunnel�Pholis clemensi�9.5�1�����50�1��44�Lacy Bryozoan�Phidolopora labiata�5�4���10�4����45�Giant Nudibranch�Dendronotus iris�5�2���10�2����46�Blackeye Goby�Rhinogobiops nicholsi�4.8�2���10�2����47�Unidentified Sculpin��4.8�1�14.3�1������48�China Rockfish�Sebastes neblosus�4.8�2�����25�2��49�Grunt Sculpin�Rhamphocottus richardsoni�4.8�1�14.3�1������50�Rock Greenling�Hexagrammos lagocephalus�4.8�2�14.3�2������

Island increased dramatically during the 1970`s and early 1980s, with a peak count of about 4,500 in 1984. Although the species has continued to expand its range northward, wintering numbers as of 2004 have slowly declined to about one-third of their peak numbers (Olesiuk 2004).

The Steller sea lion was listed as a Special Concern species under SARA in 2003. Although their numbers are increasing, they are sensitive to human disturbance while on land. The abundance of Steller sea lions in BC has increased at an overall rate of 3.5 percent per year since the early 1970s (DFO 2008). Based on estimated pup production and a range of multipliers derived from life table statistics, it was calculated that at least 20,000 and as many as 28,000 Steller sea lions currently inhabit coastal waters of BC (DFO 2008). Race Rocks (XwaYeN) is not a breeding site but is used as a haulout site during the non-breeding season, September to May. Both male and female Steller sea lions from all age-classes, except newborn pups, can be found on Race Rocks (XwaYeN) (Demarchi and Bentley 2004). Protection of year-round and winter haulout sites is listed as an action item in the Steller sea lion management plan (Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2008).

A single Northern fur seal was observed at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) by the lighthouse keeper between 1974 and 1982 (Wright and Pringle 2001). Although Race Rocks (XwaYeN) is within their North America range, there have only been incidental occurrences recorded at Race Rocks (XwaYeN).

Surveys were conducted on pinnipeds and marine birds at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) by LGL Ltd. for the 14 month period between October 2002 and November 2003 (52 monitoring sessions) (Demarchi et al 1998). The purpose of this study was to document how Race Rocks (XwaYeN) was being utilized by these organisms and how they were impacted by human disturbance (i.e., from boats, planes and military blasting). The report identified blasting as a cause of displacement for Steller sea lions and California sea lions from their haulout site. California sea lions were also sensitive to displacement by pleasure boats and foot traffic. LGL’s study expanded on a previous study (Demarchi et al 1998) which only examined the impacts of military blasting, by looking at other anthropogenic disturbances.

Update on Birds

A list of 45 species of birds observed at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) was included in Appendix 6 of the assessment report written by Wright and Pringle (2001). This list was compiled from data collected by the Wardens logs (1997-1999), unpublished data from Pearson College students and the 1997 Christmas Bird Count. Since 1997, volunteers for Bird Studies Canada have conducted an Annual Sooke Christmas Bird Count at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) over the course of one day, held during the Christmas week. This survey takes a snapshot of the number of winter bird species present and their relative abundance. The information is collected, amassed into a central database and used to monitor the status of resident and migratory birds over time from over 2000 localities across Canada, the United States, Latin America and the Caribbean.

Birds counted during the 1997 to 2007 Christmas Bird Counts at Race Rocks (XwaYeN), including birds observed within the MPA boundaries, are presented in raw data format in Table 2. Gulls and alcids represent the most common groups of birds observed. Data collected from the Christmas Bird Count can be used in a time series to document changes in species composition and note new species observed in the area. The number of different bird species reported by the Christmas Bird Count within the MPA has increased from 45 species (as documented in Wright and Pringle 2001) to 64 species. Unfortunately, the one day enumeration does not provide enough information to conduct a detailed analysis of bird populations for this one location. Weather conditions have varied over the years, including �Table2: Bird species documented during the Annual Christmas Bird Count at Race Rocks and the surrounding waters. No survey completed in 2003 & 2008 due to poor weather conditions. Surveyors did not land on Great Race in 2007 due to weather conditions.

Common Name�Scientific Name �1997�1998�1999�2000�2001�2002�2003�2004�2005�2006�2007�2008��Double Crested Cormorant�Phalacrocorax auritus�14�13�38�85�80�60��79�200�0�6���Brandt’s Cormorant’s �Phalacrocorax penicillatus�81�4�12�6�60�320��735�1000�950�5���Pelagic Cormorant�Phalacrocorax pelagicus�14�4�20�14�12�20��110�20�20�42���Common Murre�Uria aalge�6�20�6000�19�40�3600��21�600�4500�45���Black Oystercatcher�Haematopus bachmani�64�17�1�25�16�39��16�35�22�0���Black Turnstone�Arenaria melanocephala�27�30�25�51�6�18��25�45�5�2���Surfbird�Aphriza virgata�22�0�0�3�6�1��3�0�0�0���Rudy Turnstone�Arenaria interpres�1�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�0�0���Sanderling�Calidris alba�1�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�1�2���Pigeon Guillemot�Cepphus columba�1�25�3�6�8�0��0�0�0�2���Marbled Murrelet�Brachyramphus marmoratus�0�0�0��6�0��0�6�6�0���Ancient Murrelet�Synthliboramphus antiquus�0�12�2�0�0�342��0�1200�24�6���Pacific Loon�Gavia pacifica�0�3�0�6�14�4��0�40�0�4���Common Loon�Gavia immer�0�0�1�0�1�0��0�4�0�1���Red Throated Loon�Gavia stellata�1�1�0�0�0�0��0�0�0�1���Canada Goose�Branta canadensis�0�0�0�0�0�0��18�20�20�0���Harlequin Duck�Histrionicus histrionicus�23�6�46�9�2�30��4�30�7�0���Long-tailed duck�Clangula hyemalis�0�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�0�3���Bufflehead�Bucephala albeola�0�0�24�123�60�0��9�0�0�65���Surf Scoter�Melanitta perspicillata�18�0�0�0�30�6��6�1�0�44���Common Goldeneye�Bucephala clangula�0�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�0�4���White winged Scoter�Melanitta deglandi�14�1�5�0�0�0��0�0�0�0���Red-breasted merganser�Mergus serrator�0�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�0�7���Common Merganser�Mergus merganser�0�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�0�7���Hooded Merganser�Lophodytes cucullatus�0�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�0�4���Red-necked grebe�Podiceps grisegena�0�1�0�0�0�0��0�4�0�8���Western Grebe�Aechmophorus occidentalis�0�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�1�9���Mew Gull�Larus canus�23�5�1200�89�15�1200��4400�80�80�40���Thayer’s Gull�Larus thayeri�390�213�48�220�530�2000��450�600�2200�10���Herring Gull�Larus argentatus�3�0�2�3�8�12��0�1�4�0���Ring-billed Gull�Larus delawarensis�0�0�0�0�0�0��1�0�0�0���Iceland Gull�Larus glaucoides�0�0�0�0�1�0��0�0�1�0���California Gull�Larus californicus�0�0�0�0�0�2��0�0�0�0���Western Gull�Larus occidentalis�0�2�1�2�1�1��0�0�1�0���Glaucous Winged Gull�Larus glaucescens�83�40�151�61�720�800��175�150�100�15���Bonapartes Gull�Chroicocephalus philadelphia�0�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�650�0���Rhinocerous Auklet�Cerorhinca monocerata�1�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�0�0���Merlin�Falco columbarius�0�0�1�0�0�0��0�0�0�0���Peregrine Falcon�Falco peregrinus�0�0�0�0�0�1��0�0�1�1���Bald Eagle,Immat.�Haliaeetus leucocephalus�3�8�13�11�2�0��2�1�3�5���Bald Eagle, adult�Haliaeetus leucocephalus�5�4�1�5�4�0��3�1�3�2���Killdeer�Charadrius vociferus�0�0�1�0�0�0��0�0�0�0���Rock Sandpiper�Calidris ptilocnemis�0�0�6�8�9�5��0�0�0�0���Black Bellied Plover�Pluvialis squatarola�0�0�0�1�0�0��0�0�0�0���Red-necked Phalarope�Phalaropus lobatus�0�0�0�0�0�114��0�0�0�0���American Pipit�Anthus rubescens�0�0�0�0�0�0��1�0�0�0���European Starling�Sturnus vulgaris�0�7�0�83�8�0��4�3�5�0���Song Sparrow�Melospiza melodia�0�4�0�0�0�3��3�1�0�0���Savannah Sparrow�Passerculus sandwichensis�0�4�0�2�0�0��0�0�0�0���North Western Crow�Corvus caurinus�7�3�0�10�0�0��1�0�0�0���Brown Pelican�Pelecanus occidentalis�0�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�1�0���Great Blue Heron�Ardea herodias�0�0�0�0�0�0��0�0�0�2�����1997�1998�1999�2000�2001�2002�2003�2004�2005�2006�2007�2008��Species Count/Year��51�51�51�50�51�51�0�51�51�51�51�0��

some years where conditions were too stormy to complete the survey (1993) or land the boat at Great Race for the terrestrial portion of the survey (2007). In addition, high wind speeds and wave heights have resulted in low bird counts in some years (1998, 2005, and 2007). Conducting wintertime bird census is challenging at Race Rocks due to prevailing southeast winter winds and variable seas. However surveys at this time of year are valuable as they take into account migratory species that overwinter along BC’s coast.

Race Rocks (XwaYeN) has been surveyed for pelagic cormorant (Phalacrocorax pelagicus) nests every few years since 1955 as part of a larger assessment of the South Coast by the British Columbia Ministry of the Environment. In 1987, 120 nest sites were observed (Chatwin et al. 2001), and in 1989, 152 nests were observed (Vermeer 1992). In 2009, T. Chatwin and H. Carter surveyed for breeding cormorants in the Strait of Georgia, however zero were observed at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) (T. Chatwin pers. comm.). Cormorant nesting studies have shown a 54 percent decrease in number of nest observed in the Strait of Georgia between 1987 to 2000 (Chatwin et al. 2001). This decline could be due to changes in prey availability (Pacific herring, gunnels, shiner perch and salmon), predation by other birds (eagles, crows and gulls) and/or disturbance from boat traffic (REF???).

Glaucous-winged gulls (Larus glaucescens) also nest at Race Rocks (XwaYeN), though the population has declined since its peak in the 1980s (L. Blight pers. comm.). Their nesting activity has been monitored by UBC researchers, and in 1989, 424 nests were observed at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) (K. Morgan pers. comm.). Surveys completed in 2009 at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) by Louise Blight (UBC), Chris Blondeau (Pearson College) and Adam Harding (Pearson College) reported 115 nests on Great Race and zero on the other islands (L. Blight pers comm).

Pigeon Guillemots (Cepphus columba) and Black oystercatchers (Haematopus bachmani) also use Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as a breeding site however there has been no direct monitoring of their nesting success.

Recent Ecological Studies

In addition to this and the assessment report by Wright and Pringle (2001), ecological studies have been completed at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) to primarily answer either scientific research questions or provide an educational opportunity for students. Any and all research or educational activities that take place in the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) ecological reserve require a permit issued by BC Parks. Pearson College acts on behalf of the province of BC, as custodians of the Ecological Reserve, administering research permits and monitoring access to Rack Rocks (XwaYeN). Research conducted on Race Rocks (XwaYeN) is detailed on the External Research page on the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) website ( HYPERLINK “http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/research/researchexternal.htm” http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/research/researchexternal.htm) and is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3: Scientific Research Activities that have taken place at Race Rocks (from racerocks.com)

TIMELINE

ORGANIZATION

RESEARCH SUMMARY

1996 – 2004

Pearson College

Inventories of the tidepools on Great Race by students

Measurements of physical and chemical properties of the tidepools

2000

Pearson College

Analysis of the ecological niche of an anemone, Anthopleura elegantissima

2000

Pearson College

Study of the factors that affect intertidal zonation of a marine algae, Halosaccion glandiforme

2002�Pearson College�Development of a digital herbarium featuring images of over 40 species of marine algae

HYPERLINK “http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/algae/ryanmurphy/total.htm” http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/algae/ryanmurphy/total.htm

2002

Duke University

Collection site for PhD thesis on the systematics and evolution of hydrocorals using morphological and molecular biology

This work established that there is no genetic variation in colour morphs of purple and pink Stylaster corals (Allopora)

2002

Pearson College

Student directed study on the epiphytic community of a marine algae, Pterygophora californica

2003

LGL Ltd.

Assess the effects of natural and human-caused disturbances on marine birds and pinnipeds at Race Rocks over a 14 month period

2004

University of Victoria

Conducted field experiments exploring suspension feeders’ nutritional ecology and the role of dissolved substance as a food source for marine organisms

2005

Pearson College

Installation of automated weather station

2005

EnCana

Began installation of demonstration tidal power generation project

2006

Archipelago Marine Research Ltd.

Monitoring the impact of the tidal turbine generator, including the various stages of construction

2008

University of British Columbia

Master’s research developing a model-based approach to investigate Killer Whale exposure to marine vessel engine exhaust

Results demonstrate that wind angle had the largest effect on killer whale exposure to CO and NO2 and that the exposure levels to pollutants that occasionally exceeded the Metro Vancouver Air Quality Objectives (i.e. with low wind speeds, and mixing heights)

2009

AXYS Technologies

Deployed wind resource assessment buoy

Designed to assist offshore wind farm developers in determining the available wind resources at potential wind farm sites

2009

Pearson College

Assessment of the power generated by the tidal turbine generator at various current speeds

Potential or Existing Trends in Environmental Conditions

Race Rocks (XwaYeN) is a series of islets that create a complex habitat along the seafloor resulting in an area of high species richness. However, it does not exist in isolation and is surrounded on one side by the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Strait of Georgia on the other side and influenced by the larger northeastern Pacific Ocean. The waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) are not immune to environmental forcers. Environmental forcers are potential or existing environmental conditions that have a significant influence on the environmental quality of the region.

Changes to global and regional climate

The climate in British Columbia has changed over the last 50 years, with average air temperature becoming higher in many areas (BC Ministry of Environment 2006). Changes have occurred in several aspects of the atmosphere and surface that alter the global energy budget of the Earth (Solomon et al. 2007). The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the national science academies of eleven nations, including Canada and the United States, have recognized that the Earth’s atmosphere is warming and that human activities that release greenhouse gases are an important cause (BC Ministry of Environment 2006). Although several of the major greenhouse gases occur naturally, increases in their atmospheric concentrations over the last 250 years are due largely to human activities (Solomon et al 2007). These gases include methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and carbon dioxide (CO2). The concentration of atmospheric CO2 has increased from a pre-industrial value of about 280 ppm to 379 ppm in 2005 (Solomon et al 2007). The increase in greenhouse gases warms the atmosphere and affects the temperature of air, land, and water, as well as patterns of precipitation, evaporation, wind, and ocean currents. The rate of warming averaged over the last 50 years (0.13°C ± 0.03°C per decade) is nearly twice that for the last 100 years (Solomon et al 2007). Climate change impacts on the ocean include sea surface temperature-induced shifts in the geographic distribution of marine biota and compositional changes in biodiversity, particularly at higher latitudes (Gitay et al 2002). Sea surface temperature can influence life processes in marine organisms such as recruitment, growth and activity rates.

Observed warming over several decades has been linked to changes in the large-scale hydrological cycle such as: increasing atmospheric water vapour content; changing precipitation patterns, intensity and extremes; reduced snow cover and widespread melting of ice; and changes in soil moisture and runoff (Bates et al 2008). Simulations of greenhouse-warming scenarios in midlatitudinal basins of the United States, predict shorter winter seasons, larger winter floods, drier and more frequent summer weather, and overall enhanced and protracted hydrologic variability (Loaiciga et al 1996). Pressures to the Georgia Basin as a result of climate change include continued increases in air and sea surface temperature (SST), and changes in precipitation rates and sea-level in the region (REF???). This will be characterized by less rainfall in the summer and heavier rainfalls and frequent storms in the late fall and winter. These changes in the hydrological cycle will impact the Fraser River, a watershed fed by snowpack. Changes to the freshwater output will also alter salinity levels in the Georgia Basin. Reduction in the snowpack will alter the output of the Fraser River in the summer months. It has not been determined whether or not climate change will also amplify the effects of existing ocean-atmospheric cyclic weather patterns, such as El Niño Southern Oscillation and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (Folland et al 2001, McPhaden et al 2006). Both of these weather patterns produce cycles of cold, productive ocean conditions and warm, less productive ocean conditions, both of which have been observed and documented for decades.

The result of climate change on the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) ecosystem is expected to be increased stress on many of the organisms that are found there. Changes in the timing and volume of freshwater runoff will affect salinity, sediment and nutrient availability, as well as moisture regimes in coastal ecosystems (Bates et al 2008). This will alter the range of habitat available and community structure at Race Rocks (XwaYeN). Sea surface temperature is correlated closely with the structure of intertidal communities, and thermal or desiccation stress caused by elevated air temperatures can have strong effects on intertidal biota, particularly in the upper intertidal (Barry et al 1995). Intertidal sites that are exposed to greater temperature and salinity extremes may become unfavourable. It is not known how fluctuations in these water properties will impact subtidal organisms. Changes in oceanic temperature and circulation patterns cause changes in production of the phytoplankton (single-celled algae) that form the base of the oceanic food chain (BC Ministry of Environment 2006). Changes to production of phytoplankton may impact organisms that feed in the waters of the Juan de Fuca Strait. Rising sea-levels and increased storm activity caused by climate change has the potential to alter the shape and size of the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) archipelago. The analysis of sea level records shows that relative sea levels have been rising in Vancouver and Victoria at a rate of 3.1 cm/50 years (BC Ministry of Environment 2006). Islands are important refuge sites for both pinnipeds and birds. The alteration of the available shoreline could potentially reduce the area available for pinnipeds to haulout for moulting, breeding and resting. Changes in island size may also impact the area available as nesting sites for breeding birds.

El Niño/La Niña Southern Oscillation and Pacific Decadal Oscillation

The El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle is the strongest natural variation of Earth’s climate on year-to-year time scales, affecting physical, biological, chemical, and geological processes in the oceans, in the atmosphere and on land (McPhaden et al 2006). The ENSO cycle consists of alternating warm El Niño and cold La Niña events. El Niño occurs due to changes that are not fully understood in the normal patterns of trade wind circulation in the tropical Pacific Ocean. Under normal conditions, trade winds move eastward along the equator, carrying warm surface water to northern Australia and Indonesia and causing upwelling of cooler water along the South American coast. For reasons not yet fully understood, these trade winds can sometimes be reduced, or even reversed. The result of this reversal produces warmer surface waters off the coast of North and South America. These warmer waters move northward along the Pacific coast of North America and push cooler, productive water below it producing an El Niño event. La Niña occurs when the reverse atmospheric and oceanographic conditions are present and results in cooler, nutrient rich waters along the Pacific coast.

Since the 1990s there has been an increase in the frequency and intensity of El Niño events. Table 4 identifies conditions on the Pacific coast of North America from 1950 – 2007 as either a strong or weak El Niño or La Niña or as a neutral year in which the Southern Oscillation did not have a strong impact on weather conditions. The multivariate ENSO Index (MEI) (Figure 5) is used by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to monitor the Southern Oscillation. The index measures the observed departure from a standardized value for six variables: sea-level pressure, zonal and meridional components of the surface wind, sea surface temperature, surface air temperature, and total cloudiness fraction of the sky. Measurements are taken from locations across the tropical Pacific. El Niño years are characterized by positive MEI values and La Niña years are characterized by negative MEI values.

Table 4: Account of ENSO for El Niño and La Niña Years 1950-2007

HYPERLINK “http://www.smc-msc.ec.gc.ca/education/elnino/comparing/enso1950_2002_e.html” http://www.smc-msc.ec.gc.ca/education/elnino/comparing/enso1950_2002_e.html

Year

Classification

Year

Classification

Year

Classification

1950-51

Moderate La Niña

1970-71

Moderate La Niña

1990-91

Weak El Niño

1951-52

Neutral

1971-72

Neutral

1991-92

Strong El Niño

1952-53

Weak El Niño

1972-73

Moderate El Niño

1992-93

Weak El Niño

1953-54

Neutral

1973-74

Strong La Niña

1993-94

Neutral

1954-55

Moderate La Niña

1974-75

Weak La Niña

1994-95

Weak El Niño

1955-56

Moderate La Niña

1975-76

Moderate La Niña

1995-96

Weak La Niña

1956-57

Neutral

1976-77

Weak El Niño

1996-97

Neutral

1957-58

Strong El Niño

1977-78

Weak El Niño

1997-98

Strong El Niño

1958-59

Weak El Niño

1978-79

Neutral

1998-99

Moderate La Niña

1959-60

Neutral

1979-80

Weak El Niño

1999-2000

Strong La Niña

1960-61

Neutral

1980-81

Neutral

2000-01

Neutral

1961-62

Neutral

1981-82

Neutral

2001-02

Neutral

1962-63

Neutral

1982-83

Strong El Niño

2002-03

Moderate El Niño

1963-64

Weak El Niño

1983-84

Weak La Niña

2003-04

Neutral

1964-65

Weak La Niña

1984-85

Weak La Niña

2004-05

Neutral

1965-66

Moderate El Niño

1985-86

Neutral

2005-06

Neutral

1966-67

Neutral

1986-87

Moderate El Niño

2006-07

Weak El Niño

1967-68

Neutral

1987-88

Weak El Niño

1968-69

Moderate El Niño

1988-89

Strong La Niña

1969-70

Weak El Niño

1989-90

Neutral

Figure 5: Time series of the MEI during winter. Negative values of the MEI represent La Niña events, while positive MEI values represent El Niño events. (NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory: HYPERLINK “http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd//people/klaus.wolter/MEI/” http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd//people/klaus.wolter/MEI/)

During El Niño years some unusual species have been observed on the BC Coast. Migratory species that prefer warmer water such as Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas) and Ocean Sunfish (Mola mola) are observed farther north than usual (DFO 2006). El Niño years have produced greater than average precipitation in the winter, and lower than average precipitation in the summer (Meteorological Services Canada 2009). Although this results in greater than average precipitation, the average air temperature is warmer resulting in more rain than snow and an overall reduction in the local snowpack. For watersheds that are fed by snowmelt (such as the Fraser River) El Niño years will result in lower water levels during the summer months.

La Niña often produces climate impacts that are roughly opposite to those of El Niño (McPhaden et al 2006). For British Columbia this will result in a colder winter with above average precipitation, in the form of snowfall. During La Niña years there is increased productivity of the ocean caused by upwelling of colder, nutrient rich water along the continental slope.

The Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) is a term used to describe decadal-scale pattern of variability in the North Pacific basin. The PDO index (Mantua et al 1999) is based on the results obtained from principal components analysis of mean monthly sea surface temperature anomalies over the North Pacific Ocean averaged into 5° grids since 1900 (DFO 2006). PDO is a decadal-scale oscillation in the North Pacific sea surface temperature (SST) with alternating positive and negative phases that have lasted 20–30 years during the 20th Century (Hollowed et al 2001). The PDO signal is strongest in the North Pacific and like ENSO will produce oceanographic conditions with high productivity, though not on a global scale. The PDO can produce regional changes to prey composition and availability along the Pacific coast. Pacific salmon and selected flatfish stocks show production patterns that are consistent with the oscillations of the PDO (Hollowed et al 2001). This pattern is evident in trends of abundance for pelagic species such as sardines that are found to have successful years in the North Pacific while populations further south are struggling (Chavez et al 2003).

These changes in prey composition and availability will impact the higher trophic level species, such as pinnipeds and birds found in the waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN).

‘Natural’ changes in species composition

Marine ecosystems are dynamic and must respond to fluctuations in available resources. Natural changes in species composition reflect the resilience of the ecosystem and are not necessarily a sign of detrimental impacts to the ecosystem. Natural changes can include changes to prey composition, availability and seasonality. These natural fluctuations often impact several trophic levels in the food web by either a reduction in prey availability or an absence of a preferred prey type.

Northern elephant seals birthing pups at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) in 2009 and 2010 may be an example of natural changes in species composition as the most northern rookery for Northern elephant seals was previously considered to be in central California. However, it is not known at this time if this is a significant expansion in breeding range or an anecdotal occurrence involving a few animals. It is also not known if there are any other occurrences of Northern elephant seals breeding north of their known range along the West Coast of North America.

Invasive Species

Invasive species are organisms that are not native to a region. They may have been intentionally introduced for commercial reasons (e.g., Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas and Manila clams, Venerupis philippinarum) or they may have been unintentionally introduced through ballast water from ocean-going vessels (e.g., Green crab, Carcinus maenas) seafood packaging (e.g. Sargassum) or other vectors of transmission. All introduced species require a vector or mode of transmission and pathways (routes taken) of invasion. Common vectors of transmission include ballast water and hull fouling from ocean-going vessels, derelict ships, and shellfish aquaculture. It has been estimated that over 117 alien invasive species have established populations in the Strait of Georgia or along its shoreline (Transport Canada 2009a).

Not all introductions result in the establishment of an invasive species. Successful invaders are able to easily adapt to different environmental conditions and compete with native species for food and habitat. Often, introduced species do not have a natural predator in their new environment and are capable of taking over the ecosystem niche of another organism. Invasive species can reduce or destroy ecosystem functions and habitat. Species introductions cause biodiversity loss, can be detrimental to native populations and create vulnerable ecosystems.

Race Rocks (XwaYeN) is located in close proximity to a major shipping lane for vessels destined to Vancouver or Seattle, both of which are busy seaports. Transmission of invasive species by ballast water may still be a threat to the area in spite of recent regulations for ballast water exchange due to non-compliance. The majority of the established invasive species on the coast of BC prefer sheltered waters with low wave energy such as lagoons or estuaries. Examples of successful invasions include clubbed tunicate (Styela clava) and violet star tunicate (Botrylloides violaceus), both of which are problem species for shellfish aquaculture operations. Race Rocks (XwaYeN) is located in the middle of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and is exposed to high energy waves making it an unlikely place of establishment. Although invasive species are a threat to all marine environments, the physical characteristics of Race Rocks (XwaYeN) make establishment of an invasive species challenging.

Human Significance of the Protected Features

The area has cultural significance to local First Nations. The XwaYeN (Race Rocks) area is claimed traditional territory for at least four Coast Salish First Nations people; Beecher Bay First Nation, T’Sou-ke Nation, Songhees Nation and Esquimalt Nation. The term “XwaYen” is from the Klallem language for the place called Race Rocks. The nutrient rich waters of this area provides a wide diversity of food fishing opportunities year round for First Nations. XwaYeN (Race Rocks) is believed to be the gateway to the Salish Sea and is seen as an icon of the region, ecosystem and traditional territories of the Salish people.

Since 1977, faculty, students and staff at Pearson College have been involved with Race Rocks (XwaYeN). The college is committed to explore and expand its research and education opportunities available at Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as well as maintain a long term presence as the custodian of the Ecological Reserve. While the area has typically been used for marine biology research and field trips, diving and assisting other researchers to the area, effort has been directed by the college towards ecological restoration to mitigate the ecological footprint from former operations. In addressing the concern about environmental impacts from site visits during the 1980s and 1990s, a website was launched in 2000 to support non-commercial education through live streaming video (www.racerocks.com).

Race Rocks (XwaYeN) provides opportunities for recreational activities as well as public awareness and education on its unique ecological features. Its close proximity to urban areas means that Race Rocks (XwaYeN) is independently accessed by the public for boating, fishing, diving and wildlife viewing. Boaters may use the waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as a thoroughfare to other areas, shelter from the elements, a reference point for navigation or a general point of interest. Race Rocks (XwaYeN) has been recognized as an important sport fishing destination since western settlement with anglers seeking Pacific salmon, halibut, lingcod, rockfish, prawns and crabs. Since 1900, Race Rocks (XwaYeN) has gained worldwide attention by divers for its marine diversity as well as its walls, pinnacles, crevices and high currents. While divers enjoy the underwater ecosystem, tourists and researchers to the area have engaged in marine wildlife viewing, typically between the months of April to October. The important tidal upwelling due to the unique bathymetric features at Race Rocks (XwaYeN), acts as a haven for a significant assortment of flora and fauna.

Changes to Ecosystem Management Since 2001

Race Rocks was designated an Ecological Reserve in 1980 by the BC Government. Under the Ecological Reserve designation only non-consumptive use is permitted. The area is closed to both commercial and recreational fisheries by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). In September 1998 Race Rocks was proposed as a Pilot MPA (Area of Interest) by DFO.

In 2003 the Species at Risk Act was enacted by the federal government. This legislation protects species at risk and their critical habitat. The Act also requires the development of a recovery and management plans. These documents outline short-term and long-term goals for protecting and recovering species at risk. Race Rocks is home to two species that have been listed under SARA: 1)Northern Abalone (threatened), and 2) Steller sea lion (special concern). Transient killer whales (threatened) have also been observed in the area.

In 2004 Race Rocks became a Rockfish Conservation Area (RCA), and part of the network that consists of 164 sites coast-wide. RCAs were designed to protect inshore rockfish and lingcod and their habitat from recreational and commercial fishing pressures. The RCA designation prohibits any fishing activities (both recreational and commercial) that would harm rockfish stocks. Race Rocks was selected as a RCA because the island and surrounding seabed were already listed as an Ecological Reserve and the complex geography of the area provides ideal habitat for inshore rockfish. Figure 5 shows the boundaries of the RCA to the 40 m depth contour line.

Assessment of the Area of Interest

Conservation Objectives

Based upon our knowledge of the area and results of consultations, the conservation objectives below were developed, in order to identify the ecological features requiring protection in the Rocks (XwaYeN) proposed MPA.

The 1st order conservation objective for Race Rocks (XwaYeN) is proposed as:

To protect and conserve an area of high biological productivity and biodiversity, providing habitat for fish and marine mammals, including threatened and endangered species.

The 2nd order conservation objectives for Race Rocks (XwaYeN) would be:

Impacts from human activities in the area will not compromise the conservation of biodiversity and ecosystem function of the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area.

Build a knowledge base to define and understand biodiversity and ecosystem function using best science and TEK/LEK.

Monitor biodiversity and ecosystem function.

Monitor and evaluate management effectiveness to ensure management is contributing toward achievement of the overarching Conservation Objective.

Pressures from human activities in or near the proposed Marine Protected Area (MPA)

Wildlife enthusiasts travel to Race Rocks (XwaYeN) to experience the diverse marine life the area has to offer. While tourism activities, such as diving, whale watching, wildlife viewing and boating are common and beneficial activities to Race Rocks (XwaYeN), they can have adverse effects on the marine environment and the inhabitants. Whether intentional or unintentional, recreational activities in this area may result in animal harassment by altering their natural movements through the water and on land. In addition, illegal fishing within the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) ecological reserve by recreational boaters may be an issue.

The Department of National Defence’s (DND) military buffer zone for the WQ (Whiskey Quebec) military training area is partially located in the waters of the proposed Race Rocks (XwaYeN) MPA. While training activities do not take place within the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) MPA boundary, Bentinck Island, located approximately 2 km to the North, is a training site for the use of explosives for the Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Esquimalt. Studies have been conducted on Race Rocks (XwaYeN) to document the impact of blasting and other anthropogenic disturbances on the marine mammals and birds (Demarchi et al 1998, Demarchi & Bentley 2004). Their results found that Steller sea lions had the greatest sensitivity to blasting of all the species monitored and Northern elephant seals were the most tolerant. Among sea birds, cormorants appeared to be more sensitive to blasting than gulls or pigeon guillemots. Some mitigation measures have been proposed to reduce the impact of blasting at Bentinck Island. These include a reduction of the number of blasts during the harbour seal pupping season (June through September), attempting to muffle the sound of the blast by surrounding the charge with sand bags and evaluating the feasibility of a new blasting site on Bentinck Island. In addition to noise, blasting may expose the marine environment to toxic minerals that are found in the explosives.

Vessel traffic in the Strait of Juan de Fuca poses a threat to the ecosystem of Race Rocks (XwaYeN). Juan de Fuca Strait vessel traffic zones have the highest traffic volumes in BC (BC Ministry of Environment 2006). The BC government, in response to oil spills in Washington and Alaska, completed a coastal inventory and shoreline oil sensitivity mapping analysis. The Ministry of Environment developed the BC Marine Oil Spill Prevention and Preparedness Strategy and the BC Marine Oil Spill Response Plan (BC Ministry of Environment 2007). This work has identified the level of risk for different habitat types and regions of the coast as well as established a framework for an integrated response to an oil spill. Due to Race Rocks (XwaYeN) location and proximity to shipping lanes, the islets are susceptible to oil spills. However, the shoreline of southwest Vancouver Island has been classified as low sensitivity to long-term impacts from an oil spill.

Trans-oceanic vessels in the Strait of Juan de Fuca also pose a threat to the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) ecosystem through ballast water exchange, as this has been documented as a vector for invasive species. In 2006, Transport Canada developed ballast water regulations as part of the Canadian Ballast Water Program that require vessels to exchange their ballast water in the open ocean before they arrive at a Canadian port (Transport Canada 2009b). All vessels are required to document the ballast content and the locations were they have exchanged ballast water.

Other threats to the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) ecosystem include aerial over flights that may disturb pinnipeds and birds. Pollution from industrial, agricultural and residential sources will also have an impact on the marine environment. Increased development in the Victoria area and recent interest by the public in marine conservation issues has increased the awareness and interest in Race Rocks (XwaYeN). This increased interest could cause increased pressures as more members of the public visit Race Rocks (XwaYeN).

Activities that may be compatible with the Conservation Objectives

Wildlife viewing currently takes place in the waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as well as on the islets themselves. For observing marine wildlife, “BeWhaleWise” (2009) has produced guidelines stating boaters should slow down to speeds less than 7 knots when within 400 metres of a whale, keep clear of the whales path and do not position the vessel closer than 100 metres to any whale ( HYPERLINK “http://www.BeWhaleWise.org” www.BeWhaleWise.org). These guidelines also apply when observing pinnipeds and birds on land. These guidelines were developed to minimize human impacts to marine wildlife while allowing for viewing opportunities. Subject to operators adhering to these guidelines, wildlife viewing is considered compatible with the proposed MPA.

SCUBA diving is an activity that is likely compatible with conservation objectives for the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) MPA when undertaken with minimal impact to marine life. PADI project AWARE (2007) has developed guidelines for divers to protect the underwater environment while diving. Low impact diving would involve not collecting any living or dead organisms, ensuring that the diver’s buoyancy level is appropriate so as not to disturb the seafloor, not feeding or disturbing marine wildlife, and ensuring that dive vessels do not set an anchor line onto the substrate.

Race Rocks (XwaYeN) has been used as a field site for scientific research and education by Pearson College as well as other researchers. Currently, all parties interested in conducting scientific research within the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) ecological reserve require a BC Ecological Reserve permit and clearance from the Province of BC (administered by Pearson College). Research activities that contribute to the scientific knowledge of biodiversity and ecosystem function and knowledge of species at risk are compatible with the conservation objectives of this area.

Scientific monitoring and surveillance activities carried out to monitor marine life as well as those activities directed towards conservation and protection may have an impact on the fauna at Race Rocks (XwaYeN). Along the south coast of BC, overflights for pinniped stock assessment and creel surveys take place. This work is, at times necessary to achieve the conservation objectives of the MPA and to measure changes to the ecosystem and its functions.

Activities that are incompatible with the Conservation Objectives

Commercial and recreational fishing and other resource extraction activities are not compatible with the conservation objectives of the proposed MPA. Commercial fishing has not been permitted since 1990 and recreational hook and line fishing has not been permitted since 2005.

Wildlife viewing may be compatible within the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) MPA; however, harassment of the wildlife is not compatible with the conservation objectives.

The island of Great Race and the seabed nearby contain a number of manmade structures. These include the historic lighthouse, housing and power generation facilities on Great Race as well as the underwater turbine and infrastructure used by the tidal current project to generate environmentally sustainable electricity. These structures were built before the establishment of the MPA. However, further development that could impact the marine ecosystem within the MPA boundary is not compatible with the conservation objectives for the MPA.

References

Adkins, B.E. 1996. Abalone surveys in south coast areas during 1982, 1985 and 1986. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2089:72-96.

Barry, J.P., C.H. Baxter, R.D. Sagarin, S.E. Gilman. 1995. Climate-related, long-term faunal changes in a California rocky intertidal community. Science 267: 672-675.

Bates, B.C., Z.W. Kundzewicz, S. Wu and J.P. Palutikof, Eds., 2008. Climate Change and Water. Technical Paper of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC Secretariat Geneva. 210pp.

BC Lighthouse Data. 2009. Accessed on Oct. 21st, 2009. HYPERLINK “http://www-sci.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/osap/data/SearchTools/Searchlighthouse_e.htm” http://www-sci.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/osap/data/SearchTools/Searchlighthouse_e.htm

BC Ministry of Environment, 2007. British Columbia Marine Oil Spill Response Plan. Province of British Columbia. Victoria, B.C. 103pp.

BC Ministry of Environment, 2006. Alive and Insepararble. British Columbia’s coastal environment: 2006. Province of British Columbia. Victoria, B.C. 335pp.

Be Whale Wise. 2009. Accessed on Nov. 17th, 09. HYPERLINK “http://www.bewhalewise.org/” http://www.bewhalewise.org/

Chatwin, T.A., M.H. Mather, T. Giesbrecht. 2001. Double-crested and pelagic cormorant inventory in the Strait of Georgia in 2000. BC Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. 20pp.

Chavez, F.P., J. Ryan, S.E. Llutch-Cota, M. Niquen. 2003. From anchovies to saradines and back: Multidecadal change in the Pacific Ocean. Science. 299 (5604) 217 – 221.

COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Northern Abalone Haliotis kamtschatkana in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 48 pp. ( HYPERLINK “http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm” www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm).

Crawford, W.R. and J. R. Irvine. (2009). State of physical, biological, and selected fishery

resources of Pacific Canadian marine ecosystems. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2009/022. vi + 121 p.

Demarchi, D.A. and M.W. Bentley. 2004. Effects of natural and human-caused disturbance on marine birds and pinnipeds at Race Rocks, BC. LGL Report. Prepared for Department of National Defence, Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt.

Demarchi, D.A., W.B. Griffiths, D. Hannay, R. Racca, S. Carr. 1998. Effects of military demolitions and ordnance disposal on selected marine life near Rocky Point, southern Vancouver Island. LGL Report EA1172. Prepared for Department of National Defence, Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt. 113p.

DFO, 2006. State of the Pacific Ocean 2005. DFO Sci. Ocean Status Report. 2006/001.

DFO. 2008. Population Assessment: Steller Sea Lion (Eumetopias jubatus). DFO Can. Sci.

Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2008/047.

Folland, C.K., T.R. Karl, J.R. Christy, R.A. Clarke, G.V. Gruza, J. Jouzel, M.E. Mann, J. Oerlemans, M.J. Salinger and S.-W. Wang, 2001: Observed Climate Variability and Change. In: Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Houghton, J.T.,Y. Ding, D.J. Griggs, M. Noguer, P.J. van der Linden, X. Dai, K. Maskell, and C.A. Johnson (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 881pp.

Gitay H., Surárez, A., Watson, R.T., Dokken, D.J. 2002. Climate change and biodiversity. Technical Paper of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC Secretariat, Geneva, 86 pp.

Hollowed, A. B., S. R. Hare and W. S. Wooster. 2001. Pacific basin climate variability and

patterns of northeast Pacific marine fish production. Prog. Oceanog. 49(2001): 257-282

Loaiciga H.A., J.B. Valdes, R. Vogel, J. Garvey, and H. Schwarz. 1996. Global warming and the hydrologic cycle J. of Hydrology, Volume 174, Number 1, pp. 83-127(45)

McPhaden, M.J., S.E. Zebiak, M.H. Glantz. 2006. ENSO as an integrating concept in earth science. Science. 314 (5806) 1740 – 1745.

Meteorological Services Canada – El Niño. 2009. Accessed Nov. 20th, 2009. HYPERLINK “http://www.smc-msc.ec.gc.ca/education/elnino/index_e.cfm” http://www.smc-msc.ec.gc.ca/education/elnino/index_e.cfm

NOAA – Earth System Research Laboratory. Accessed Nov. 20th, 2009. HYPERLINK “http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd//people/klaus.wolter/MEI/” http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd//people/klaus.wolter/MEI/

Olesiuk, P.F. 2008. An assessment of population trends and abundance of harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) in British Columbia. NMMRC Working Paper, Dept. Fisheries and Oceans, Canada, National Marine Mammal Review Committee Meeting, November 17 – 20, 2008, Nanaimo, British Columbia. DFO Can. Sci. Adv. Sec. 2009/005. vii + 44p.

Olesiuk, P.F. 2004. Status of sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus and Zalophus californianus) wintering off southern Vancouver Island. NMMRC Working Paper, Dept. Fisheries and Oceans, Canada, National Marine Mammal Review Committee Meeting, April 20 23, 2004, St. Andrews, New Brunswick. DFO Can. Sci. Adv. Sec. 2004/009. viii + 95p.

PADI project AWARE. 2007. Accessed on April 22nd, 10. HYPERLINK “http://www.projectaware.org/” http://www.projectaware.org/

REEF. 2009. Reef Environmental Education Foundation Volunteer Survey Project Database. World Wide Web electronic publication. HYPERLINK “http://www.reef.org” \o “www.reef.org” www.reef.org, Accessed Nov. 13th, 2009

Rothaus, D.P., B. Vadopalas, and C.S. Friedman. 2008. Precipitous declines in pinto

abalone (Haliotis kamtschatkana kamtschatkana) abundance in the San Juan

Archipelago, Washington USA, despite statewide fishery closure. Canadian

Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 65:2703-2711.

Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, R.B. Alley, T. Berntsen, N.L. Bindoff, Z. Chen, A. Chidthaisong, J.M. Gregory, G.C. Hegerl, M. Heimann, B. Hewitson, B.J. Hoskins, F. Joos, J. Jouzel, V. Kattsov, U. Lohmann, T. Matsuno, M. Molina, N. Nicholls, J. Overpeck, G. Raga, V. Ramaswamy, J. Ren, M. Rusticucci, R. Somerville, T.F. Stocker, P. Whetton, R.A. Wood and D. Wratt, 2007: Technical Summary. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M. Tignor and H.L. Miller (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

Transport Canada. 2009a. Ship-mediated Introductions. Accessed on Nov. 20th, 2009.

HYPERLINK “http://www.tc.gc.ca/marinesafety/oep/environment/ballastwater/introductions.htm” http://www.tc.gc.ca/marinesafety/oep/environment/ballastwater/introductions.htm)

Transport Canada. 2009b. Canadian Ballast Water Program. Accessed on Dec. 15, 2009.

HYPERLINK “http://www.tc.gc.ca/marinesafety/oep/environment/ballastwater/menu.htm” http://www.tc.gc.ca/marinesafety/oep/environment/ballastwater/menu.htm

Vermeer K., K.H. Morgan, P.J. Ewins. 1992. Population trends of pelagic cormorants and

glaucous-winged gulls nesting on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Pages 60-64 in: K

Vermeer, RW Butler, KH Morgan (editors) The ecology, status and conservation of marine and shoreline birds on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Canadian Wildlife

Service Occasional Paper No. 75. Canadian Wildlife Service. Ottawa, ON.

Wallace, S.S. 1999. Evaluating the effects of three forms of marine reserve on Northern

Abalone populations in British Columbia, Canada. Conservation Biology 13:882-

887.

Wright, C.A., and J.P.Pringle. 2001. Race Rocks Marine Protected Area: An Ecological Overview. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2353:93p.

Personal Communications

Lousie Blight, PhD Candidate, Centre for Applied Conservation Research, UBC

Trudy Chatwin, Rare and Endangered Species Biologist, Ministry of Environment

Joanne Lessard, Research Biologist, Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Ken Morgan, Marine Conservation Biologist, Canadian Wildlife Services

PAGE

PAGE 6

PAGE 29

Clarification needed from Garry Fletcher – Do we know that the lighthouse records this information or is it at the shoreline station at Race Rocks where this data is recorded. In addition, it has been noted that William Head has recorded data since 1921 – however on-line it is indicated that data has been recorded at William Head since 1954

Garry Fletcher – Lighthouse vs shoreline station and William Head (date discrepancy)?

Sarah/Miriam do you have a reference here?

Sarah/Miriam – can we clarify that this number is correct as it is different then what is in W&P = 1233 indiv in 1984.

Sarah/Miriam, do you have a reference here?

Doug Biffard: Is this an accurate reflection of the authority of BC Parks and the roles and responsibilities of Pearson as custodians?

Sarah – reference?

Race Rocks (XwaYeN)

Proposed Marine Protected Area Ecosystem Overview and Assessment Report

Executive Summary

Background

Race Rocks (XwaYeN), located 17 km southwest of Victoria in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, consists of nine islets, including the large main island, Great Race. Named for its strong tidal currents and rocky reefs, the waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) are a showcase for Pacific marine life. This marine life is the result of oceanographic conditions, supplying the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) area with a generous stream of nutrients and high levels of dissolved oxygen. These factors contribute to the creation of an ecosystem of high biodiversity and biological productivity.

In 1980, the province of British Columbia, under the authority of the provincial Ecological Reserves Act, established the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve. This provided protection of the terrestrial natural and cultural heritage values (nine islets) and of the ocean seabed (to the 20 fathoms/36.6 metre contour line). Ocean dumping, dredging and the extraction of non-renewable resources are not permitted within the boundaries of the Ecological Reserve. However, the Ecological Reserve cannot provide for the conservation and protection of the water column or for the living resources inhabiting the coastal waters surrounding Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as these resources are under the jurisdiction of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO).

The federal government, through the authority of the Oceans Act (1997), has established an Oceans Strategy, which is based on the principles of sustainable development, integrated management and the precautionary approach. Part II of the Oceans Act also provides authority for the development of tools necessary to carry out the Oceans Strategy, tools such as the establishment of Marine Protected Areas. This federal authority will complement the previously established protection afforded the area by the Ecological Reserve, by affording protection and conservation measures to the living marine resources.

Under Section 35 of the Oceans Act, the Governor in Council is authorized to designate, by regulation, Marine Protected Areas (MPA) for any of the following reasons:

the conservation and protection of commercial and non-commercial fishery resources, including marine mammals and their habitats;

the conservation and protection of endangered or threatened species and their habitats;

the conservation and protection of unique habitats;

the conservation and protection of marine areas of high biodiversity or biological productivity; and

the conservation and protection of any other marine resource or habitat as is necessary to fulfill the mandate of the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans.

In 1998, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans announced Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as one of four pilot Marine Protected Area (MPA) initiatives on Canada’s Pacific Coast. Race Rocks (XwaYeN) meets the criteria set out in paragraphs 35(1) (a), (b) and (d) above. Establishing a MPA within the Race Rocks (XwaYeN) area will provide for a more comprehensive level of conservation and protection for the ecosystem than can be achieved by an Ecological Reserve on its own. Designating a MPA within the area encompassing the Ecological Reserve will facilitate the integration of conservation, protection and management initiatives under the respective authorities of the two governments.

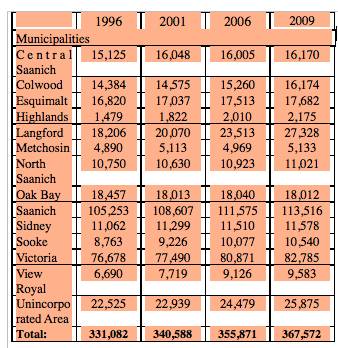

The Race Rocks (XwaYeN) proposed Marine Protected Area (MPA) is 268.5 hectares in size and encompasses the majority of seamounts surrounding Great Race, the largest of the islets (Figure 1). It is important to note that the selection of Race Rocks (XwaYeN) as a proposed MPA preceded the current framework for selecting Areas of Interest (AOI), which requires areas to be identifed as either ecologically and biologically significant areas (EBSA), or areas that contain ecologically significant species (ESS). Though Race Rocks (XwaYeN) was not identified through an EBSA or ESS process, the area does provide habitat to ecologically significant species (e.g. Northern abalone, Stellar sea lions) and would likely qualify as an EBSA due to the oceanographic and bathymetric (Figure 2) features and conditions. In future, proposed Marine Protected Areas, now referred to as Areas of Interest (AOI), will be selected through Integrated Management initiatives that employ EBSA and ESS identification methods.