the Pilot Project at

Graduate Research Project submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Management

at Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

~ September 1999 ~

© Copyright 1999

by Louise V. Murgatroyd

Marine Affairs Program

The undersigned hereby certify that they have read and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate Studies for acceptance a graduate research project entitled Managing Tourism and Recreational Activities in Canada’s Marine Protected Areas: the Pilot Project at Race Rocks, British Columbia, by Louise V. Murgatroyd in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Management.

Supervised by:

Dr. Martin Willison

School for Resource and Environmental Studies

Dalhousie University

Signature

Date Dalhousie University

Date: ??3 September 1999

Author:?Louise V. Murgatroyd

Degree: Master of Marine Management Convocation:October

Year:1999

Permission is herewith granted to Dalhousie University to circulate and to have copied for non-commercial purposes, at its discretion, the above title upon the request of individuals or institutions.

Signature of Author

The author reserves other publication rights, and neither the graduate project nor extensive extracts from it may be printed or otherwise reproduced without the author’s written permission.

The author attests that permission has been obtained for the use of any copyrighted material appearing in this graduate project (other than brief excerpts requiring only proper acknowledgement in scholarly writing), and that all such use is clearly acknowledged.

List of Abbreviations?*

Acknowledgements?*

1. Introduction?*

2. Tourism, Recreation and Marine Protected Areas?*

2.3 Economics, Conservation and Education?*

2.4 Coastal Tourism and Marine Protected Areas in British Columbia?*

2.4.1 Tourism?*

2.4.2 Marine Protected Areas?*

3. The Pilot Marine Protected Area Project at Race Rocks?*

3.3 Tourism and Recreation at Race Rocks?*

3.3.1 Whale Watching/Wildlife Viewing?*

3.3.2 Scuba diving?*

3.3.3 Recreational Fishing?*

3.3.4 Kayaking/Boating?*

3.3.5 Research and Education?*

3.4 Impacts from Recreational Activities?*

3.4.1 Threats to Ecosystem and Wildlife?*

3.4.2 Conflicts?*

3.5 Current Management Regime?*

3.5.1 BC Parks and Pearson College?*

3.5.2 The Light-keepers?*

3.6 Management Issues for Tourism and Recreation at Race Rocks?*

4. Selected Examples of Current MPA Management Practice for Tourism and Recreation?*

4.3 The Fathom Five Marine Park?*

4.4 The Bonaire Marine Park?*

5. Managing Tourism and Recreation: Recommendations for Race Rocks?*

5.3 User Fees?*

5.4 Codes of Conduct/Wildlife Viewing Guidelines?*

5.5 Education and Interpretation?*

5.6 Tour Operator and Staff Training?*

5.7 Permits?*

5.8 Partnerships for Stewardship/Stakeholder and Community Participation?*

5.9 Custodians?*

5.10 Monitoring and Research?*

6. Conclusion?*

7. Appendices?*

7.3 Appendix III: Example of Incident Report Form?*

7.4 Appendix IV: Whale watching guidelines?*

8. References?*

Marine tourism is a major component of a massive global tourism industry. Extensive visitation to coastal and marine areas has lead to marine environmental degradation, compromising the very values that make these environments attractive to tourists. Marine protected areas (MPAs) strive to conserve biodiversity and ecological processes, many of which coincide with the above-mentioned values. Tourism and MPAs can have a mutually beneficial relationship: MPAs provide venues for tourism and tourism, through education and awareness-raising, can create support for marine conservation, MPAs and other integrated coastal management strategies.

Race Rocks, a group of tiny islands near Victoria, British Columbia, is one of five national pilot MPA project sites currently being examined by Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The site hosts abundant and diverse wildlife and is heavily visited tourists and recreational users from the greater Victoria area. These include whale watching operators, scuba divers and recreational fishers. While already protected as a provincial ecological reserve, the pilot MPA project will pursue additional strategies involving government, industry and other stakeholders to ensure that negative impacts from mounting visitor use are minimised.

Examples of effective management strategies for tourism and recreation in existing MPAs around the world are provided, such as the Great Barrier Reef and Bonaire Marine Parks. Recommendations are made for the pilot MPA at Race Rocks and include a combination of government and industry regulation, comprehensive education and interpretation programs, and extensive consultation with relevant stakeholders to ensure effective management strategies which encourage compliance among users and require minimal enforcement.

DFO??(Department of) Fisheries and Oceans Canada

EMC??environmental management charge

EPGC??The Economic Planning Group of Canada

ER??ecological reserve

FFNMP?Fathom Five National Marine Park

GBRMP?Great Barrier Reef Marine Park

GBRMPA?Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

LUCO??Land Use Co-ordination Office

MEF??Ministère de l’Environnement et de la Faune (Québec)

MMRG?Marine Mammal Research Group

MPA??marine protected area

OUC??Ontario Underwater Council

SFAB??Sport Fishing Advisory Board

SSLMP?Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park

Further thanks go to the staff and students of Pearson College, and the lightkeepers Carol and Mike Slater, who showed me what an extraordinary place of wonder and learning is located at Race Rocks and who continue to care for it. Garry Fletcher and Angus Matthews were extremely helpful in providing unlimited access to an extensive database of information and contacts. Special thanks go to Chris Blondeau who, in addition to becoming a friend, took a shivering tropical diver and immersed her in the chilly waters of the Pacific Ocean in a scuba tank, thus providing an introduction to the phenomenal wealth of marine life at Race Rocks. Without this experience, my understanding and appreciation of the Rocks would have indeed been deficient. Thanks also to Dr. Joe MacInnis, a source of inspiration to all who are concerned about the world’s oceans, for his continued interest and enthusiasm for my progress in the master’s program, and whose deep appreciation for Race Rocks will help to secure its future for the benefit of all Canadians.

Finally, to my family and friends, for whom there are not words sufficient to express . . .

for a glimpse into the nature of that mysterious realm than the delivery, in 1998, of the first-ever tourists to the grave of the Titanic, buried deep beneath the surface of the sea.

Despite this apparent fascination, the extent of our knowledge and understanding of the seas remains but a drop in the oceanic bucket. And much to our discredit as a species, we pollute, deplete, plunder and generally degrade the marine environment with an ignorance that borders on wilful. Long utilised as a receptacle for waste and considered to be an endless bounty of resources, the health of the oceans is failing due to human abuse. As a result, efforts world-wide now concentrate on more integrated approaches towards managing the marine environment to stem a tide of degradation that could spell ecological disaster for the planet.

To this end, marine protected areas (MPAs) have emerged as an important tool in ocean conservation, and the management of tourism and recreation activities within MPAs has become an important issue for the protection of marine and coastal resources. The reasons for this are two-fold: tourism has great potential as an activity that can have a minimal impact on the marine environment while generating income for the communities at its borders; and, as greater numbers of tourists seek more educational experiences in natural environments, MPAs provide invaluable settings for the dissemination of marine ecological information, creating corps of aware and concerned citizens to support ocean and coastal conservation.

As increasing human demands are placed upon ocean resources by tourism, in addition to other marine sectors, ensuring the compatibility of tourist activities with the protection of an MPA’s resources and environmental quality is critical. Poor planning and management in the past, coupled with tremendous growth in the industry world-wide, has compromised the health of marine environments everywhere. Furthermore, emerging evidence of negative impacts associated with tourism development, often labelled nature-tourism or eco-tourism, has called into question their status as relatively ‘benign’.

In keeping with growing efforts to establish MPAs around the world, Canada has recently embarked on a national initiative to establish MPAs in the in- and off-shore environments along its extensive coastlines. To test strategies that deal with a variety of management issues for the establishment of MPAs, several pilot projects are underway. It is hoped that these pilot MPAs will ultimately receive formal designation under the Oceans Act, setting the example for successive efforts. One such project is the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area located just outside Victoria, British Columbia. Announced in September of 1998, the Race Rocks pilot site provides a venue for the consideration of a number of management issues particularly with respect to tourism and recreation. Of significant cultural, historical and ecological value to the local tourism industry, the site has experienced considerable growth in visitation over the past decade, raising concerns regarding the impacts of this activity on its distinctive marine ecosystem.

The management plan for the Race Rocks Marine Protected Area Pilot Project is in its iterative stages of development and public consultation by relevant government agencies. This research project is intended to provide an overview of the main issues involved with respect to the tourism and recreation portion of this plan, and to highlight some further areas for research. It also brings together some of the tourism management literature as it pertains to MPAs, and offers some recommendations for consideration at Race Rocks. It is hoped that the research project may serve as a starting point for more detailed analysis and further discussion.

2.1 Coastal and Marine Tourism

Tourism is one of the largest economic sectors world-wide with marine and coastal tourism comprising a major component of the industry (Anonymous 1995). World Tourism Organization statistics for 1997 record 612 million international tourist arrivals, with expenditures of US $443 billion, and the industry continues to grow (World Tourism Organisation 1998). Coastal and marine tourism includes “any activities, attractions or facilities/services which take place on the ocean or along the coastline or which involve a marine-based theme . . . such as sailing, sea kayaking and whale watching, coastal sightseeing and touring and attractions, parks accommodations, festivals and special events with a marine theme or location” (EPGC 1997, p. i). The popularity of coastal tourism stems from its ability “to provide both terrestrial and aquatic recreational opportunities to tourists during a single trip” (Bailey 1998, p. 31).

Coastal areas are often an important factor in the selection of a tourist destination as evidenced by the mass tourism market that has evolved around the “sun, sea and sand” destinations of coastal tropical nations. However, the popularity of the sea-side vacation is not limited to the tropics: a 1997 study on marine tourism in Nova Scotia found that 88% of tourists surveyed indicated that the seacoast was either critical or important to the selection of Nova Scotia as their holiday destination (EPGC 1997). Unfortunately, intensive visitation to coastal environments has resulted in a host of negative impacts to the environment. Habitat such as mangroves and grasslands has been lost as areas are cleared for development. The construction of resorts and hotels coupled with beach

management efforts has lead to coastal erosion. Inadequate or non-existent sewage treatment facilities in many areas means that human wastes are often discharged directly into the sea both from land and from ships, while anchors from small recreational craft and giant cruise liners damage coral reefs and other benthic organisms. Finally, fishery and invertebrate resources are harvested to depletion to supply the tourist trade in both restaurants and souvenir shops.

2.2 Tourism and Marine Protected Areas

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature provides a widely accepted definition of MPAs as follows: “any area of intertidal or subtidal terrain, together with its overlying waters and associated flora, fauna, and historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by legislation to manage and protect part or all of the enclosed environment” (Kelleher & Kenchington 1992). In addition to the protection of marine biodiversity, often from the very threat of damage due to visitation, providing tourism and recreational opportunities has been a major impetus for the of MPAs around the world. Overall objectives for marine parks include the provision of “protection, wise use, understanding and enjoyment” (GBRMPA 1999a) of ecosystems “for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations” (Parks Canada and MEF 1995, p. 5). Implicit in these statements is the fact that people will, and indeed should, visit these areas in such a way that the ecosystem remains intact and unharmed for future appreciation. In order to achieve this end, “[a]ctive environmental planning and resource protection programs are essential for effective management to balance park uses with the capabilities of the resource to sustain such use indefinitely” (Marion and Rogers 1994, p. 154).

The values that MPAs are established to protect are coincident with those sought after by tourists. For example, in the case of scuba dive tourism, “[t]he special features and values of [MPAs] – the reasons they were declared in the first place – are also the reasons that such areas attract divers” (Davis and Tisdell 1996, p. 230). For most marine tourism and recreation activities, such values are associated with those aesthetic and amenity qualities which rely on healthy marine ecosystems. These include flora and fauna that are unique, diverse or abundant, good water quality and visibility, unspoiled or pristine landscapes and the absence of over-crowding (Davis and Tisdell 1995).

2.3 Economics, Conservation and Education

Tourism is emerging as a major economic sector of marine industries against a backdrop of dwindling fishery resources in our seas. Its potential to provide a means of supplemental, if not alternative, livelihood for coastal communities is being tapped around the world. Bailey (1998) writes that “communities that rely on tourism as their economic base are in many ways quite similar to communities that are dependent upon logging, fishing, agriculture or any other natural resources system” (p. 31). MPAs, like their terrestrial counterparts, have become venues for various forms of tourism which utilise natural environments and provide economic development opportunities for local communities. Davis and Tisdell (1996) write that “[t]he granting of protected area status may also make these areas better known and easier to promote, again leading to heavier recreational use by groups” (p. 230). In addition to economic benefits to local communities, revenue generated from protected areas can be channelled into maintenance costs and funding for research.

Controlled marine tourism has been characterised as non-extractive and non-degrading and has therefore not been associated with the negative impacts of such extractive industries as commercial fishing or minerals exploitation (Agardy 1993). However, heavy or poorly managed visitation to protected areas, no matter how well-intentioned, can result in loving an area ‘to death’. As Post (1994) writes, “economic benefits have little significance in the context of the aim of national parks and protected areas (the preservation of ecosystems) if these benefits are generated in a way which destroys the ecosystem” (p. 336). Furthermore, “[p]ermitting unlimited and unregulated tourism development and use of protected environments will ultimately erode the very values which contributed to their designation as parks and reserves (Marion and Rogers 1994, p. 154). Therefore, tourism activities in protected areas, and indeed all natural environments, must be conducted in such a way as to uphold conservation principles.

Public education and awareness-building effected through interpretation programs in protected areas are one of the most important aspects of protected area management whenever visitation is permitted. The benefits of education, such as generating support for biodiversity protection and conservation, are accrued not only to the visitor population, but to local communities, tour and associated industry operators, and all other relevant stakeholders.

Since the tourism and recreational activities permitted within MPAs utilise the natural resources protected therein, these activities are generally considered to fall under the category of eco-tourism. Recent eco-tourism literature defines the term largely in keeping with the definition provided by the Ecotourism Society which states that eco-tourism is “responsible travel to natural areas which conserves the environment and sustains the well-being of local people” (1997). The eco-tourism debate rages in the literature with respect to proper definitions and the types of activities which fall into this category, and it is not the intention of this author to enter in to such a debate. However, it must be acknowledged that the eco-tourism label has become subject to over-use in the tourism industry and today connotes almost any activity that involves the natural environment. Taking responsibility for conservation and regard for local communities are central to eco-tourism in addition to active education programs which increase awareness.

Modern tourists have greater experience in international travel than the tourists of the past and are “more likely to seek educational components in their tourism experiences” (Aiello 1998, p. 52). MPAs are well-suited to accommodate this demand and visitation has its benefits, as Ballantine (1995) writes:

2.4 Coastal Tourism and Marine Protected Areas in British Columbia

Tourism is a growing sector of the BC economy and the second largest export industry after forestry in the province (Tourism British Columbia). In 1998, 21.3 million tourist visits generated $8.7 billion in revenue (Ministry of Small Business Tourism and Culture 1999). The province markets itself as “Super, Natural British Columbia” and promotes tourism products and services which consist primarily of activities involving the outdoors.

In addition to its exceptional value in terms of biological productivity, fishery resources and cultural heritage, the Pacific coast contains “a vast array of recreational opportunities” (DFO and LUCO 1998, p. 9) and is popular for cruising, sailing, kayaking, wildlife viewing, scuba diving and sport fishing. Activity-specific and up-to-date information regarding marine and coastal tourism in BC is difficult to obtain. In 1989, revenues from marine-related tourism were estimated at $222 million with nearly 800 marine-based tour operators in existence (ARA Group 1991). And one recent estimate reports that “one in every three dollars spent on tourism in B.C. goes toward marine or marine-related activities” (DFO and LUCO 1998, p. 8).

Sport fishing is the most popular activity, generating the greatest amount of revenue with the largest number of operators (Price Waterhouse and ARA Consulting Group Inc. 1991). British Columbia is also well recognised internationally as an excellent dive destination offering a variety of diving on historic wrecks, artificial reefs and natural rocky reefs, all of which host diverse and colourful marine life. “In a recent divers survey, British Columbia’s coast was rated as the best overall destination in North America, even when compared to such tropical destinations as the Florida Keys, the Gulf of Mexico and southern California” (DFO and LUCO 1998, p. 9) and the industry was valued at $4 million dollars in 1993 (Eggen 1997). Clearly coastal and marine activities are a significant component of tourism in British Columbia and will be an important consideration within the context of MPAs.

There are currently 104 marine areas on BC’s coasts that have been afforded some degree of protection (DFO and LUCO 1998). These exist in the form of marine parks, ecological reserves, wildlife management areas and fisheries closures, each with specific conservation and recreation objectives, and are managed by various government agencies (DFO and LUCO 1998). The designation of MPAs in BC has occurred on a sporadic, ad hoc basis, through a variety of federal and provincial legislative instruments (DFO and LUCO 1998). However, since 1994 the provincial and federal governments have been developing a joint strategy for marine protected areas in BC resulting in the 1998 release of a discussion paper entitled Marine Protected Areas: A Strategy for Canada’s Pacific Coast (Barr et al. 1999).

The strategy identifies primary objectives for the establishment of MPAs which include the protection of biodiversity and representative ecosystems, the conservation of fishery resources and habitats, the protection of cultural heritage resources, the provision of opportunities for scientific research and the sharing of traditional knowledge, and the enhancement of education and awareness (DFO and LUCO 1998). Also included is the provision of opportunities for recreation and tourism:

(DFO and LUCO 1998, p. 13)

Providing opportunities for tourism and recreation will be an important element of the MPA strategy, in view of the province’s growing outdoor tourism industry and indeed considerable evidence of the strong links between tourism and MPAs from around the world.

As the initial phase of this program, DFO has selected five pilot MPA projects which represent a ‘learn-by-doing’ approach to MPA selection and designation (DFO and LUCO 1998). Four of the projects are located off the Pacific coast with Race Rocks and Gabriola Passage representing the nearshore environment, while two projects have been established offshore at the Bowie Sea Mount and Endeavour Hydrothermal Sea Vent. The fifth project is located at the Gully off the coast of Nova Scotia. These projects have been designed to test various aspects of MPA implementation including the determination of objectives, opportunities for stakeholder partnerships and co-management arrangements, the establishment of criteria for the evaluation of MPA proposals, and co-ordination between various levels of government and non-government agencies (DFO and LUCO 1998).

The pilot project at Race Rocks, a group of small islets located 17 km from Victoria, off

the southern tip of Vancouver Island (Figure 1), was designated in 1998. Specific elements to be tested there focus on federal-provincial partnership and complementary management plans and strategies, and the application of joint federal and provincial legislation as the area is already protected by the province (DFOa). Stakeholders in the area include DFO, BC Parks, First Nations, tourism operators, research and education interests, recreational fishers and boaters, and the Department of National Defence which owns much of the adjacent coastal land and conducts underwater explosives testing in the area.

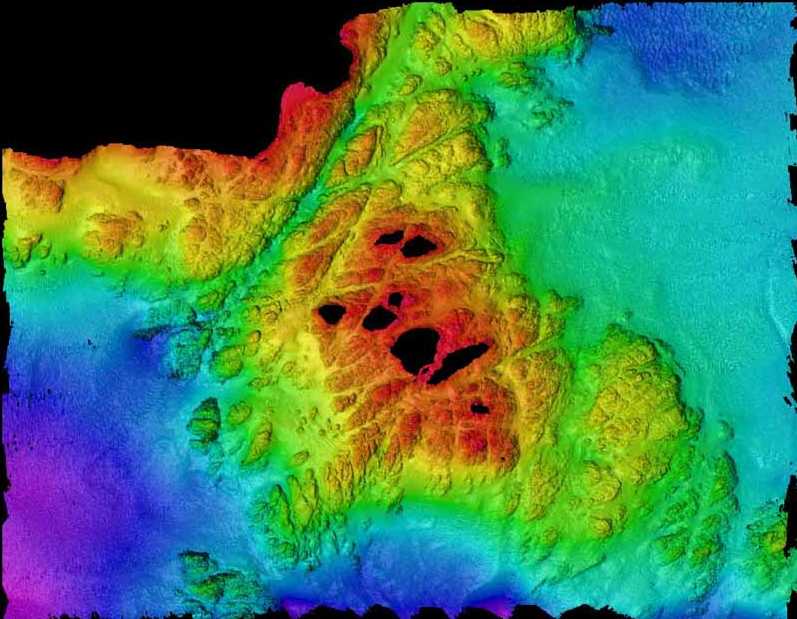

3.1 Geography, Ecosystem and Heritage

The nine islets which comprise Race Rocks have a total area above sea-level of less than one hectare. Strong tidal currents “racing” past the rocks at up to seven knots give the site its name. The islets form the peak of a submarine mountain and the substrate is characterised as continuous rock consisting of cliffs, chasms, benches and surge channels (Figure 2) (BC Parks 1998). The area is nestled between the straits of Juan de Fuca and Georgia, in the transition zone between open ocean and coastal waters, and currents supply nutrient-rich waters from Pacific upwellings, the estuarine-fed waters of the Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound.

Race Rocks is distinguished for the wide variety and number of marine mammals found there including Northern and California sea lions, harbour, northern fur and elephant seals, river otters, Dall’s and harbour porpoises, orcas and gray whales. Many sea birds also nest on the rocks including pelagic and Brandt’s cormorants, pigeon guillemots, black oystercatchers and glaucous-winged gulls (DFOa). Invertebrate species present include octopi, sea stars, a variety of sponges, corals, sea anemones, giant barnacles, sea grasses, giant kelp and other algae, and hydroids (DFOa; BC Parks 1998). Numerous examples of fish species can also be found including salmon, halibut, Ling cod and wolf eel (DFOa; BC Parks 1998).

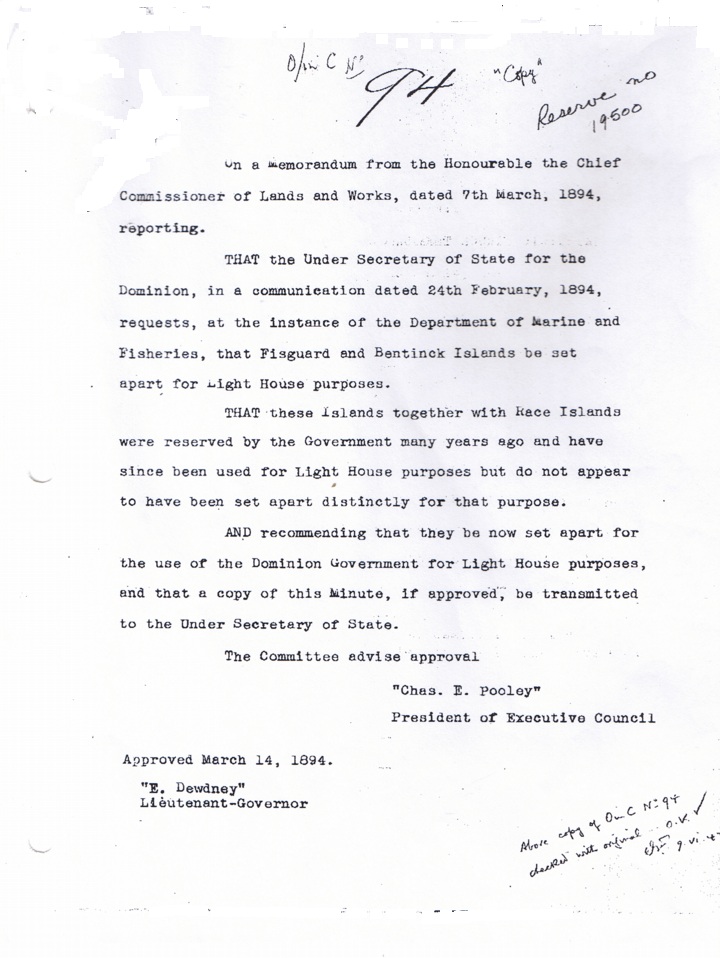

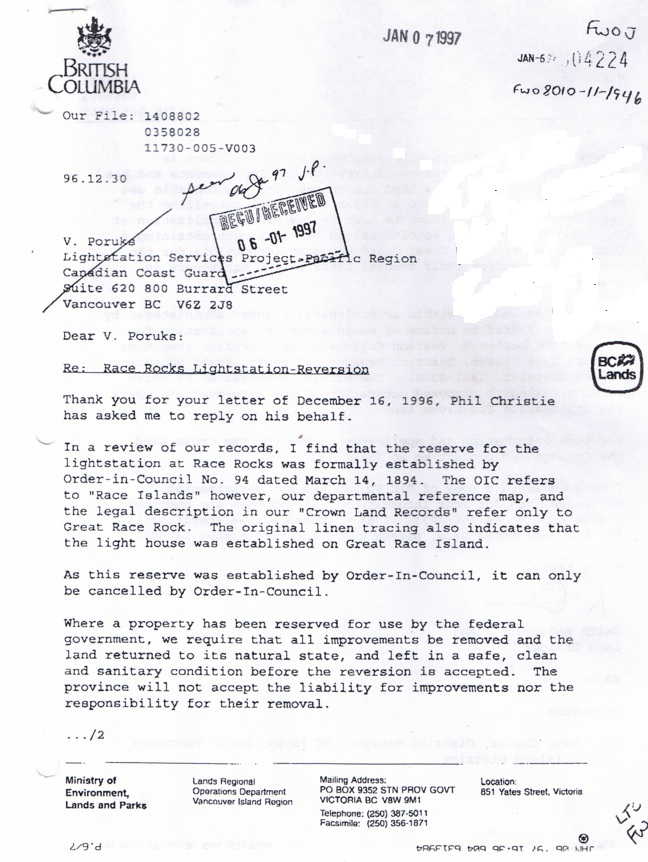

Great Race Rock is the largest of the islands and is not included in the Ecological Reserve. It houses the second oldest lighthouse tower on Canada’a Pacific coast. The tower was built in 1860 from granite shipped from England as ballast. An important aid to navigation which warns mariners off the dangerous rocks, the station became fully automated in 1997. Two houses remain on the island which accommodate the former lightkeepers, who now act as custodians, and researchers. Since automation, the federal government has been working to restore the land around the lighthouse, previously under lease, to the province. Historically , local First Nations have harvested a number of species at the site though these uses are not well-documented at present (Fletcher 1999). Consultation with these groups with respect to the pilot MPA and the incorporation of traditional knowledge into educational programs has begun, and MPA designation will be further subject to the treaty negotiation process (DFOa; Lavoie 1998; Fletcher 1999; Matthews 1999, pers. comm.).

3.2 Race Rocks Ecological Reserve

One of the unique features of Race Rocks in terms of the pilot project is its status, since 1980, as a provincial ecological reserve (ER). ERs are established in terrestrial and marine environments throughout British Columbia for the protection of areas representative of the province’s ecology, unique habitats and rare or endangered species (BC Parks). They are further intended to provide scientific and educational opportunities and therefore tourism and recreation are not actively promoted within these sites.

The establishment of the ER at Race Rocks was initiated by a proposal put forth to the province by students and staff at the Lester B. Pearson College of the Pacific (Pearson College) who use the site extensively as part of their science curriculum. Chosen for “its unique richness and diversity of marine life,” (BC Parks) the boundaries of the reserve follow the 20 fathom/36.6 metre depth contour (Figure 3) and contain a total area of 220 hectares (BC Parks). Race Rocks has received considerable attention in local and regional print media with respect to the natural features of the area, its status as an ecological reserve and the automation of the light station.

3.3 Tourism and Recreation at Race Rocks

Race Rocks is a popular area for whale watching operators, scuba divers, recreational fishers, boaters and kayakers. Data indicating current levels of these uses at the site are largely unavailable. Rather, general information exists in the form of overall trends for visitation to the province and southern Vancouver Island, and certain water-based tourism activities in which visitors engage. In 1998, over 5.5 million visitors travelled to Victoria generating roughly $7.5 billion in revenue (Tourism British Columbia 1998). Of those who visited from outside the province, 16% participated in marine-based activities such as whale watching and boating (Tourism British Columbia 1998).

Tourism Victoria has recently begun breaking down its exit surveys of participant activities into segments and includes a “Water Based Recreation” Category. In its visitor reporting for 1998, 19.7% of parties visiting Victoria had at least one member who participated in either boating fishing or whale watching (Tourism Victoria 1999). Furthermore, whale watching and water-based recreation (i.e. boating, sailing, canoeing, kayaking and swimming) placed high in the top ten list of activities which respondents would like do on a return trip (Tourism Victoria 1999). Data such as this help to provide an overall indication of the popularity and potential for growth of certain activities but is insufficient for the needs of planning and management for the pilot MPA.

Data describing numbers of vessels operating in and around Race Rocks is also difficult to obtain. The municipality of Victoria grants licenses to tour companies operating vessels which use dock facilities in its harbour. However, vessels are classified as ‘sightseeing’ and consist of whale watching, dinner cruises, sailing charters and other activities such that whale watching/wildlife viewing is not specifically indicated. Furthermore, tour companies operate from a number of local harbours which lie in other municipalities, therefore this is not a reliable source of information. Private and commercial vessel registry is administered by either Transport Canada or Canada Customs, depending on the tonnage of the vessel, and no central database exists with respect to the commercial activities of these vessels.

The following sections will outline general use and industry profiles and levels and, for the reasons stated above, is not intended to serve as a comprehensive investigation.

3.3.1 Whale Watching/Wildlife Viewing

Wildlife viewing is by far the most prevalent tourism activity at Race Rocks. Trip sales in Victoria’s whale watching industry grew from 1400 in 1987 to 8000 in 1997 with the number of vessels increasing from five boats in 1993 to 40 in 1998 (Obee 1998). The 1998 Victoria Visitor Report recorded that 9% of non-resident visitors participated in whale watching during that year. Upon entering the visitor information centre in Victoria, the visitor is confronted with a large wall display of pamphlets promoting the activity in the greater Victoria area. The author collected 21 pamphlets advertising both dedicated whale watching operators and those offering a number of marine tourism activities of which whale watching was one.

While whales are indeed sited in the area, the majority of whale watching activities do not take place at Race Rocks itself and very few companies offer dedicated wildlife viewing tours of Race Rocks. Rather, the site is used frequently as a stop-over en route to or from whale sightings further west in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, or as an alternative, “Plan B”, site in the absence of whales (Figure 4) (Fletcher 1999). Bruce Obee, a popular BC travel writer, writes that while killer whales provide a primary attraction in the industry, “an evolving fraternity of marine-mammal aficionados is arriving, like birders, with lifelong species lists. They’re looking specifically for grey whales and humpbacks, Dall’s and harbour porpoises, Pacific and white-sided dolphins, harbour seals, California and Steller’s sea lions” (1998, p. 8). The majority of vessels are rigid-hull inflatables with a capacity of twelve passengers and two crew and are capable of high speeds in order to reach the whales. These are generally crewed by a captain and an on-board naturalist who provides whale and wildlife interpretation. Some companies combine these roles in one crew member.

The majority of Victoria’s whale watching operators are members of the Whale Watching Operators Association Northwest (WWOANW), an industry-generated organisation consisting of approximately 30 operators from Canada and the US. It was created in response to the growth of the industry in the Puget sound area and the need for communication and co-operation between operators, in addition to concerns over the welfare of the whales (Bennett 1999). In keeping with a growing trend among whale watching operators around the world, and the absence of formal regulation, the organisation has developed its own guidelines for the operation of vessels around marine mammals and birds. The WWOANW also contributes funds to various whale research organisations such as The Whale Museum at Friday Harbour in Washington’s San Juan Islands.

WWOANW members assist in the Museum’s Soundwatch program which seeks to foster stewardship and public awareness and to minimise the impacts of recreational and commercial vessels in the region (Kukat 1999, pers. comm.; Rhodes 1999, pers. comm.; The Whale Museum 1999). Curiously, very few of the Victoria-based operators advertise their membership with WWOANW, their adherence to the whale watching guidelines or contributions to whale research. Whatever the reason for this, heightening awareness of this type of participation would serve to better educate the consumer in the selection of subsequent operators in the future.

Data for diver usage at Race Rocks are also vague. In 1995, roughly 1300 divers were recorded in the guest book kept on the dock at Great Race Rock (Grant 1996). However, as many divers do not land on the island, this is not an accurate

measure. The site is offered as a regular weekend destination by one Victoria dive shop, the Ogden Point Dive Centre, which takes an estimated 500 divers per year (Bradley 1999, pers.comm.). Other dive operators in the Victoria and Sydney areas run dive charters to the site on demand by groups throughout the year A number of provincial dive societies also make use of the site, in addition to private users.

International collision regulations require that vessels engaged in diving fly a recognised dive flag (Figure 5) when divers are present in the water (CCGOBS 1999). Other vessels are advised to move at slow speeds and to remain “well clear” (CCGOBS 1999, p. 66) of these vessels. Furthermore, there is no national regulatory body for recreational scuba diving or the commercial operators that provide it.

Recreational diver training in Canada is relatively standardised throughout a number of private certification agencies. Divers are taught proper buoyancy skills to avoid injuring aquatic life and are generally encouraged by agencies and operators not to harass nor take organisms while underwater. The Race Rocks ER brochure makes further recommendations to divers in the reserve to minimise impacts to the environment:

Individuals diving with commercial operators are generally given briefings in which appropriate behaviour is encouraged and monitored (Bradley 1999, pers. comm.). However, for other individuals, compliance is purely voluntary.

Sport fishing is a very popular activity throughout the province with revenues estimated at over $7 billion for 1999 (Price Waterhouse and The ARA Consulting Group Inc. 1996). The Victoria Visitor Report to the British Columbia Visitor Study reports that 6% of non-resident visitors to Victoria engaged in salt water fishing (Tourism British Columbia). In a 1995 national sport fishery survey, approximately 200 000 angler days per year were recorded for the Victoria area, generating between $30 and $50 million dollars in associated expenditures (Gjernes 1999, pers. comm.).

Race Rocks has been characterised as an extremely popular fishing ground for local residents due both to its accessibility from Victoria and local marinas, and the natural features which make it conducive to catching fish (Gjernes 1999, pers. comm.; Kukat 1999, pers. comm.). Sport fishers take an active role in the conservation and allocation of resources, consulting on a regular basis with government through local branches of the province-wide Sport Fishing Advisory Board (SFAB). While recreational fishing of salmon and halibut remains open at Race Rocks, there are concerns over the issue of accidental, or by-catch, of other species within the reserve, particularly of rockfish which are the target of federal conservation efforts in the region. Anchoring by fishing boats is also a concern (Hawkes 1994; Slater 1999, pers. comm.).

The closest marina to Race Rocks, located at Pedder Bay, rents small charter boats which are mainly used for recreational fishing, and sells sport fishing licenses on site. Renters are given charts with the Race Rocks ecological reserve clearly outlined by a bold red line and are instructed to remain out of the reserve altogether. This is in order to avoid damage to boats from tides and currents around the rocks (Dickinson 1999, pers.comm.). Nonetheless these vessels are often observed in the reserve (Slater 1999).

Sea kayaking is becoming a popular activity in British Columbia and there are several outfitters in Victoria and southern Vancouver Island. Kayakers do make use of Race Rocks though the strong currents make it a site for experienced paddlers. One local kayaking tour operator describes kayak use in the area as minimal (Party 1999). A 1996 consultant’s report on alternative uses of automated lightstations identified Race Rocks as being particularly accessible and having good potential for sea kayaking tours and suggested that the facilities had potential for use as a bed and breakfast (Cornerstone Planning Group 1996).

Determining use levels by private boaters in MPAs is a particularly difficult, as has been found in other MPAs around the world (see Valentine et al. 1997). The lightkeepers have been recording observations of boats within the reserve since 1997 (see Appendix II) and these logs may begin to provide an indication of the level of use by this group.

Research and education are a primary objective for the establishment of ERs under the Ecological Reserve Act and were a key factor in the designation of Race Rocks. With its high concentration and diversity of wildlife and easy access, Race Rocks has been the subject of extensive research on hydroids, transient whales, abalone and nesting sea birds, in addition to a host of projects by students at Pearson College including tidepool monitoring and the installation of permanent transect pegs (Fletcher 1999). Much of this information is presented and updated on the Race Rocks website which is maintained by Pearson College.

As already mentioned, Pearson College students make use of the site extensively for field research in the Biology and Environmental Systems courses offered at the college. However, Pearson also runs a public outreach program aimed at local schoolchildren who are given a tour of the facilities at the site and an introduction to its intertidal and subtidal marine life (Fletcher 1999). Two salt water tanks are maintained on Great Race Rock containing a sampling of underwater life to be found in the reserve.

In 1992, a series of interactive educational television programs called the “Canadian Underwater Safari” was broadcast live via satellite from Race Rocks. During the programs, students from around the world were able to communicate with divers while watching live underwater video of the reserve. The College hopes to make further use of internet technology in the creation of a virtual education centre by setting up permanent cameras, both above and below water, which would offer live video feeds of Race Rocks. Partnerships are being developed with BC Tel and the BC Museum in addition to industries wishing to showcase environmentally-friendly technology such as alternative energy production by wind (Fletcher 1999, pers. comm.).

3.4 Impacts from Recreational Activities

3.4.1 Threats to Ecosystem and Wildlife

The location of Race Rocks makes it susceptible to a number of potentially harmful impacts including the danger of oil spills from high volumes of international shipping traffic in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and disturbances from explosives testing at the nearby DND facility. Visitor numbers are high for such a small area and with the wide range and increase in activity of tourism and recreational activities concerns are mounting over the impact of these activities on the wildlife. With respect to whale watching, there is a considerable body of literature on the impact of this activity on whales and research in the Pacific and elsewhere is on-going. In a study presented to the whale watching workshop at the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park (SSLMP) in May of 1998, it was shown that

However, while whales are indeed sited at Race Rocks, the primary activity of commercial whale-watching vessels in the ecological reserve is the viewing of wildlife and it is the impact of this activity that will be examined here.

Discussions with the former lighthouse keepers Mike and Carol Slater indicate that a decrease in whale sightings and changes in the behaviour of other marine mammals within the reserve has occurred in the area over the past ten years. While, the couple attribute these changes largely to the increased presence of commercial vessels in the reserve, this is an area of some debate among other users. The couple have observed numerous occasions where both commercial and recreational boaters have accidentally and intentionally harassed wildlife having, upon occasion, forced seals and sea lions to “stampede” from the rocks (Slater 1999, pers. comm.).

Managing the behaviour of recreational boaters is also an issue as highlighted by a recent article describing a whale watching encounter aboard a commercial vessel. The whale watching operators present were

(Obee 1998, p. 8)

The education of recreational boaters presents a particular challenge in the management of the reserve as there is no centralised means of providing appropriate information to these users. The presence and activities of the lightkeepers, who disseminate ER brochures and provide information to these boaters remains the most effective means of informing this group.

Sea kayaks, while generally considered to be benign due to the absence of loud engines, may also disturb wildlife. Kayakers may approach wildlife more closely than motorised vessels and their movements may be mistaken for those of predators (Obee 1998). At certain times of the year the rocks provide important breeding and nesting sites which adds a seasonal element to the susceptibility of wildlife to human activities. For instance, young seal pups are not accustomed to the presence of boats which can result in injury. Vessels have been observed to pass through the ER at high speeds and Pearson college reported the deaths of three baby seals during the summer of 1998 which were attributed to collisions with vessel propellers (Pearson College 1999).

The destruction of coral reefs from tourism and other activities has received considerable attention around the world. For instance, anchor use by dive boats provides the greatest source of damage to coral reefs associated with scuba diving (Harriott et al. 1997; and see van Breda and Gjerde 1992). Damage is caused by dragging anchors and the scraping of heavy anchor chains along the bottom as boats swing back and forth. In temperate waters however, awareness of the marine life that may be compromised is not as prevalent. At Race Rocks, anchor use also poses a threat to the “lush variety of invertebrate life including plumose anemones, starfish, nudibranchs, bryozoans, and sponges, for which the waters of British Columbia are known” and thus anchoring is prohibited in the reserve (Battley 1998).

With increasing levels of visitation to Race Rocks there exists greater potential for conflict between users of the site. In the past two years, two incidents have occurred involving scuba divers and whale watching operators. In each case, scuba divers were unable to surface due to the presence of whale watching vessels. The most recent incident sparked a legal case which is presently before the provincial courts (Bradley 1999, pers. comm.). If divers are prevented from surfacing, serious injury may result from running out of air or being run over by a boat’s propeller. And while dive vessels are required to fly a special dive flag the adequacy of the size of such flags to warn off approaching boats from a sufficient distance may also be an issue.

In the absence of a national body to regulate either of these industries, both rely heavily on the safe practice and awareness of operators, and on good communication. This is an area requiring significant attention as the safety of individuals visiting a federally protected area must be of paramount importance. Furthermore, while operators of vessels in these industries are generally prepared for the presence of each other, the question remains as to the level of awareness of the private boater or renter who may not be familiar with other users of the area.

At present, recreational boaters are not required to meet competency standards for the operation of their vessels. New standards are currently being implemented by the Canadian Coast Guard which require mandatory certification of private vessel operators through an accredited boating safety course, and that proof of such competency be carried on board. However, the completion of all phases of implementation will not occur until 2009 (CCCOBS 1999).

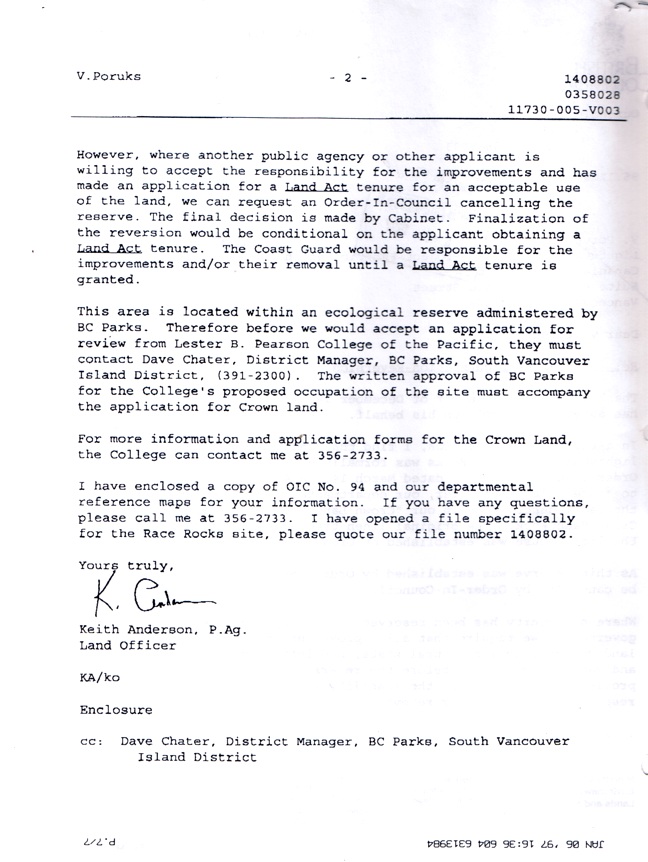

3.5.1 BC Parks and Pearson College

As an ER, the management responsibility for Race Rocks lies with the province and is administered through a program of voluntary wardens. Since the establishment of Race Rocks, this role has been performed by the staff and students of Pearson College. Commercial activities are subject to permits administered by Pearson College on behalf of BC Parks. Permit applications are available on the Pearson College website and are issued for research and filming activities (Pearson 1999b). Commercial tourism activities have thus far not been subject to the permitting process. Therefore these activities are almost purely self-regulated within the reserve.

Despite its designation in 1980, the management plan for the reserve has not been forthcoming. In 1998, a draft management plan was produced by Pearson College and BC Parks, and forms the basis for the management plan for the pilot MPA project currently under review. While tourism and recreation are not actively promoted in ERs, it is obvious that changing use patterns since the designation of the ER must be reflected in the management of the pilot MPA, such that protective measures are aimed against the impacts of such uses (Willison 1999, pers. comm.).

Robert Louis Stevenson, from The Light-Keeper

Since the automation of the Race Rocks light station in 1997, the lighthouse keepers Mike and Carol Slater, have been employed as custodians of Race Rocks by Pearson College. The couple serves an important role both in terms of observing and documenting reserve use, reporting infractions of reserve regulations, guarding against poachers of abalone and other benthic species, and educating visitors (Slater 1999, pers. comm.; Hewett 1996). In addition, the keepers provide weather reports to local marinas, take daily temperature and salinity measurements which have been collected since the early half of the century, and assist in local rescue operations (Hewett 1996; Slater 1999, pers. comm.). Whenever possible, the couple greets boaters who violate reserve regulations with the Race Rocks brochure and provide information about the reserve. Whether the Slaters will continue to serve this important function at Race Rocks remains uncertain as Pearson College relies on private fund-raising for their salaries.

3.6 Management Issues for Tourism and Recreation at Race Rocks

The primary issue for the management of tourism and recreation at Race Rocks is the lack of data on visitor use and its impacts on the ecosystem. With respect to use, information is unspecific and scattered throughout a variety of sources, consisting largely in the form of general trends for the larger Victoria area. The importance of such research needs has been well recognised in MPAs around the world for which such data is also lacking and is a growing area of research (see Valentine et al. 1997 and Crossland and Alock 1999). For Race Rocks, the situation presents a major research need for the future of the MPA to ensure informed decision-making with respect to management and planning and this has been recognised in the draft management plan. Furthermore, consideration will need to be given to determining possible use thresholds or carrying capacity (see Dixon et al 1993).

While the gaps in research are substantial, the precautionary principle currently being applied to much of ocean resource management dictates that decisions must be made based on the best available data. Its absence should not be used as rationale to delay decision-making or the implementation of precautionary measures. This principle further places the onus on the resource user to provide sufficient proof that a particular activity will have a minimal impact on the environment.

A second crucial issue for consideration at Race Rocks is that of partnerships and stakeholder participation. Federal and provincial co-operation are a significant element of the pilot project and as tourism and recreation interests play such a major role in the use of the reserve, the participation and support of these groups will be essential to controlling activities and minimising impacts, in addition to ensuring that other objectives for the site, i.e. conservation and education, are upheld. While it is unrealistic to think that all stakeholders will be completely satisfied if an MPA and its associated regulations are implemented at Race Rocks, their meaningful input into the management and planning stages will be important in securing a viable management regime for Race Rocks. Furthermore, as a pilot project, the success of partnerships displayed here will provide valuable lessons for future MPA establishment.

A third important issue for tourism at Race Rocks is ensuring that education and interpretation programs are effective and are reaching their intended audience. As stated earlier, private recreational boaters are the most challenging targets and those most in need of information. Commercial activities at Race must continue to promote environmental education first and foremost as part of the services they provide and should include information specific to the Race Rocks ecosystem and its status as an Ecological Reserve and potential MPA. Additional issues for consideration are contained in the draft management plan, stating the overarching objective with respect to visitor use and potential actions to be taken to achieve it. These are presented in Figure 4.

Ecological reserves are established to support research and educational activities. Visitation to the waters surrounding Race Rocks Ecological Reserve has been increasing, particularly those engaged in wild life viewing and diving. Uncontrolled, uninformed and excessive use could result in: behavioral changes or injury to marine mammals and seabirds; poaching of sealife; or physical injury or mortality from handling or improper dive techniques. Given the proximity of the ecological reserve to Victoria and the interest in these types of activities, commercial and recreation use will continue to grow.

Given the role of ecological reserves, uses that occur at Race Rocks should contribute to education or research objectives without negatively impacting the natural values. This may include commercial tours.

Objective:

To permit educational opportunities that have minimal impact to the ecological reserve and increase public awareness, understanding and appreciation for Race Rocks Ecological Reserve and its values.

Actions:

- Subject to an impact assessment, only issue permits for commercial activities that are educational or research oriented

- Work with the volunteer warden, Lester B. Pearson College, to provide annual orientation session for commercial operators and tour guides.

- Continue to provide public information to increase awareness of the ecological reserve, the potential of ecological impact of various activities, and the need for caution in the ecological reserve. This would include: brochure; accurate information in BC Sports Fishing Regulations; information at points of entry; mapping on marine charts and navigational guides; internet/web site.

- Work with commercial operators and researchers to develop a code of conduct within the ecological reserve to ensure protection of the natural values and to maintain a high quality educational experience. Develop a monitoring system with Lester B. Pearson College, site guardian, researchers and commercial tour operators to ensure appropriate behavior of diving and wild life viewing companies and other visitors.

- Develop an outreach program and stewards program to assist with the management, and to develop respect for the ecological reserve and its values.

- Discourage anchoring in the ecological reserve.

- As per the Ecological Reserve Regulations ensure that commercial operators in the ecological reserve have permits for their activities.

Figure 4: Management objectives and actions with respect to visitor use in the current draft management plan for the Race Rocks Ecological Reserve.

The following section provides a brief description of various MPA management plans and regimes which may offer some guidance for the pilot MPA at Race Rocks.

4.1 The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park

As one of the earliest, and indeed the largest MPAs in the world, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP) provides useful insight all aspects of MPA management, particularly with respect to multiple use, and is frequently described in MPA literature. The growth of tourism provided much of the impetus for the creation of the MPA and tourism remains the main commercial use of the park (Kenchington 1991; Alcock and Crossland 1999; GBRMPA). The GBRMP is managed by a distinct legal entity, the GBRMP Authority (GBRMPA), in addition to the Queensland Department of Environment. The primary objective of the GBRMPA is “to provide for the protection, wise use, understanding and enjoyment of the Great Barrier Reef in perpetuity through the care and development of Great Barrier Reef Marine Park” (GBRMPA 1999a). Zoning in the park affords various levels of protection from ‘general use’, in which all reasonable activities consistent with conservation are permitted, to ‘strict preservation’ in which areas are left in their natural state and free from human activity (Kenchington 1991).

Environmental issues are the key consideration for tourism development and a permit system allows new proposals to be reviewed on an individual basis, the imposition of

conditions of practice and environmental monitoring, and the collection of data on commercial tourism use (Kenchington 1991; Craik 1994; Valentine et al. 1997).

This information is compiled into a central database which includes the following fields: company name, location of activity, nature and frequency of activity, maximum number of people, permit type, type of transport, vessel name, passenger capacity, size and registration (Valentine et al. 1997).

In 1993, the GBRMPA implemented an environmental management charge (EMC) to offset rising costs of park management and reef research. Originallly set at $1 per person participating in tourism activities in the park, the EMC has been raised to $4 and is applied to commercial operators only. 25% of the revenue contributes to management activities and the remaining 75% funds research through the CRC Reef Research Centre (Alcock and Crossland 1999). The centre is a joint venture between the tourism industry and the relevant management and research agencies and conducts research on all aspects of the Great Barrier Reef, including tourism (Alcock and Crossland 1999).

Management approaches to tourism include strategic policy and planning, direct management, industry self-regulation, active partnerships and adaptive management (GBRMPA; Alcock and Crossland 1999). As Alcock and Crossland (1999) write,

Formal consultation with the industry is effected through the Association of Marine Park Tourism Operators. The GBRMPA and the marine tourism industry have developed the Great Barrier Reef Staff Certificate course to train industry staff members in reef interpretation, in addition to an “Eye on the Reef” program in which tour operators assist in ecological monitoring by recording marine life observations at the sites they frequent (Aiello 1998; GBRMPA 1999b).

4.2 The Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park

Established in 1997, the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park (SSLMP) encompasses estuarine ecosystems of the Saguenay and St. Lawrence Rivers and is the result of a joint federal-provincial partnership in the establishment of an MPA. The park experiences a variety of extractive and non-extractive uses and receives large numbers of visitors. Second only to conservation, the main objective of the park is, “[i]n co-operation with community partners, [to] teach visitors to recognize, understand and appreciate the many aspects of the Marine Park, so that they can comprehend the reason for the park, the intrinsic value of its components and the need for conserving them” (Parks Canada and MEF 1995, p. 28).

The management plan for the park identifies activities that it does not consider to involve resource harvesting including boat excursions to observe marine mammals, pleasure boating and scuba diving. The plan recognises that

(Parks Canada and MEF 1995, p. 35)

Priority actions for the park include developing appropriate management procedures and a regulatory framework for these activities, particularly for boat tours and scuba diving, in addition to further study of the impacts of recreational activities on the marine environment (Parks Canada and MEF 1995).

As at Race Rocks, whale watching and wildlife viewing are significant activities within the park. At a regional workshop on whale watching held in 1998, the issue of permits for whale watching operators was examined in light of the desire from the Marine park to develop a policy of mandatory permits for commercial tours. The policy would seek to implement a moratorium on the number of authorised wildlife-viewing vessels, ensure resource protection and passenger safety, and apply violator sanctions (Gilbert and SSLMP 1998). Proposed conditions for permits include limiting the number of vessels authorised for individual companies, the requirement of additional navigation equipment to that already required by Transport Canada, and the zoning of whale watching activities (Gilbert and SSLMP 1998). Additional conditions could include the meeting of competency standards for boat captains including certifications in Transport Canada accredited navigation, marine emergencies, use of navigation equipment, first aid and training in industry codes of conduct (Gilbert and SSLMP 1998).

4.3 The Fathom Five Marine Park

While the Fathom Five National Marine Park (FFNMP) exists in the freshwater environment of Ontario’s Georgian Bay, its management plan focuses largely on the tourism and recreation activities which comprise the major use of the park. These include scuba diving, cruising, sailing, wreck touring and recreational fishing (Parks Canada 1998). Parks Canada is the government agency charged with the management of Fathom Five. With extensive experience in the protection and conservation of biodiversity and the management of visitors in terrestrial areas, the agency is currently embarking on the establishment a system of National Marine Conservation Areas (NMCAs). This system would complement the national MPA strategy and associated legislation currently awaits parliamentary approval.

At FFNMP,

(Parks Canada 1998, p. 29)

Interpretation and education are central to public appreciation at the park and information is presented in the format of relevant themes which encompass the ecosystem, history and culture, environmental awareness and departmental messages (Parks Canada 1998). Appropriate and inappropriate activities for the park have been identified with the latter being prohibited within its boundaries.

To take the example of management strategies for one activity, scuba diving, a mandatory diver registration program has been established with the assistance of the Ontario Underwater Council (OUC) and is carried out by OUC volunteers. The program, geared towards ensuring the safety of divers at Fathom Five, highlights the importance of co-operation and participation from stakeholder groups. Furthermore, policies have been implemented to address conflicts between divers and other user groups (Parks Canada 1998). The 1998 management plan provides guidelines for the implementation of user fees to be collected in exchange for certain Park services that are in the private rather than the public interest, for example the use of campsites versus resource protection; the consideration of capacity for key visitor sites; and the use of business licenses to manage commercial operations (Parks Canada 1998).

The island of Bonaire forms part of the Dutch Caribbean in the lesser Antilles. The island’s waters, extending to the 60 metre depth contour, have been legally protected as a Marine Park since 1979. Divers provide the majority of visitation to the island (Dixon et al. 1993; De Meyer 1997). The management of the MPA clearly demonstrates the potential for the successful employment of a number of management tools and it is one of the first MPAs in the world to become entirely self-financing (De Meyer 1997). Procedures are relatively simple, but effective:

The user fees contribute further to the maintenance of the park’s mooring system, the provision of shore markers, and the maintenance of park facilities and equipment, in addition to funding a children’s outreach program, law enforcement activities and several research and monitoring projects (De Meyer 1997). While scuba diving is the main form of tourism, the strategies used to manage it should be considered for other marine activities.

Zoning is a popular tool in protected area management and is particularly effective in large areas such as the GBRMP in which multiple-uses are. In view of the small size of the area proposed for MPA designation at Race Rocks, and the similarity between the nature of activities engaged in by its users, zoning to separate activities for the area may not be practical or necessary. While some potential for conflict between tour operators has been demonstrated, the activities at Race Rocks generally require similar management approaches which would be more easily administered within a single zone.

The potential for conflict does exist between tourism and recreation and the research and educational uses of the site. Furthermore, there is considerable support for the establishment of ‘no-take’ zone in which all harvesting would be prohibited. This would be particularly appropriate in light of suggestions to expand the current boundary of the reserve to form the MPA. In this way, an outer or buffer zone could be created in which multiple-uses could take place, including current sport fishing activities (Kukat 1999, pers.comm; Fletcher 1999). Furthermore, Great Race Rock could be zoned to permit landing only at certain times of the year, to ensure maximum protection during critical seabird nesting times.

Currently, a feasibility study is underway by Parks Canada for the establishment of a much larger NMCA in the Georgia Basin region. An MPA of such size would be more on a par with the GBRMP in which zoning would be necessary for various uses, and it is thus conceivable that Race Rocks might then become a zone of higher protection within this larger area.

The installation of mooring buoys has had considerable success in tropical reef environments where damage from anchoring is widespread. In British Columbia’s coastal waters, the Underwater Council of British Columbia has established a program of mooring ball installation to mitigate similar impacts (Battley 1998). The majority of diving at Race Rocks however is drift diving which, as mentioned previously, requires mobile surface support from vessels. Furthermore, the dock at Great Race offers limited moorage. Boats anchoring in the reserve appear to be private recreational vessels whose operators are either unaware of, or deliberately contravene, no-anchoring regulations. This group should be targeted for further efforts at education and awareness-raising.

Craik (1994) writes that user pays policies are “based on the philosophy that people who benefit from the use of a public good or property, especially for commercial purposes, should contribute to the cost of managing or protecting that property” (p. 344). The implementation of a user fee at Race Rocks has been suggested for commercial operations at Race Rocks:

(Fletcher 1999)

The EMC discussed in the section on Australia’s GBRMP is indicative of how this fee can be utilised further to assist in the collection of important data on visitor use and commercial activities. As in the Australian example, the problem remains as to how to implement such a fee for private recreational users. While interviews with tour operators indicated support for nominal fees, concerns were raised regarding the dedication of funds for use at Race Rocks and not ‘general revenue.’ Guarantees would have to be put in place and the use of a non-government entity such as Pearson College, to administer the funds, should be considered.

5.4 Codes of Conduct/Wildlife Viewing Guidelines

General guidelines for the conduct of all commercial tourism activities will need to be incorporated into the management of the pilot MPA. This should include wildlife interaction protocols, in addition to interactions between operators from different sectors, e.g. whale watchers and divers, in order to avoid potential conflict. As previously indicated, the WWOANW has developed a comprehensive set of guidelines for its members. The guidelines cover behaviour around whales, pinnipeds, birds, porpoises and other whale watching vessels. Of further significance is the final section of the guidelines which deals with research and education. Members are advised to “support local whale research by providing written records of sighting information to bona fide research groups and through association approved financial support of selected research activity” (WWOANW 1999).

These guidelines have not been widely available until recently and are now available on the internet. Industry adherence to the guidelines should be better promoted by individual operators and a modified version created for distribution to clientele considered. Furthermore, companies should promote their participation in local research and conservation efforts. Increasing awareness of these activities will promote further support for research and conservation and will allow for more informed decision-making on the part of the public in the selection of responsible tour operators.

Concomitant with industry guidelines should be the development of government guidelines, particularly for dissemination to the recreational boating public. In its Laurentian region, the DFO has already published such information in its leaflet, There are limits TO OBSERVE! The leaflet contains information on federal marine mammal regulations, a code of ethics, rules of conduct, information on how to approach whales and how to report disturbance incidents in the region (DFOb). This type of information would be highly appropriate and useful for recreational boaters in the Pacific region.

While individual dive and kayak operators generally brief clients on ecological considerations in their respective activities, codes of conduct could also be developed for these users to ensure proper standards for behaviour. For instance, Victoria kayak operator Ocean River Sports provides training in conservation ethics for its staff and promotes environmentally-friendly practices among its clientele (Party 1999, pers. comm.). Dive operators provide briefings on appropriate behaviour but again this could be standardised for the industry through more formal codes of conduct for behaviour within an MPA.

5.5 Education and Interpretation

The provision of opportunities for education is a central function of MPAs and is a desirable and highly effective strategy against negative impacts from tourism. Education programs also reduce the need for, and cost of, formal means of enforcement (Causey 1995). Commercial tourism activities at Race Rocks are, on the whole, oriented at providing an educational experience and this must remain their primary objective. Tour operators must be encouraged to include information specific to the natural history of Race Rocks and its ecosystem when taking clients there (Willison 1999, pers. comm.). Furthermore, information regarding its protected status as an ecological reserve and pilot MPA should be provided to generate recognition and support for such initiatives. There is a need for consistency in this respect and it would be appropriate for industry, in partnership with other agencies such as local universities and museums, to develop a minimum standard of information to be included in interpretation, to ensure that correct and relevant information is being provided.

Education and interpretation are particularly important for private recreational users who are considerably more difficult to target. Broader efforts aimed at educating the recreational boating public on general conduct and appropriate behaviour in coastal waters, including ERs and MPAs would seem to be a realistic approach. To this end, the distribution of the booklet Protecting BC’s Aquatic Environment: A Boater’s Guide, a joint publication by DFO, Environment Canada and BC’s Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks should continue. The booklet covers a number of aspects of environmentally responsible boating, including respect for marine wildlife. The British Columbia Tidal Waters Sport Fishing Guide contains information on the location and regulations of MPAs, species conservation efforts and whale watching guidelines and is also an important contribution to awareness-raising.

Despite new Coast Guard regulations requiring private boaters to enrol in an accredited operator proficiency course, the curriculum for this course contains no elements of marine environmental education or respect for wildlife (Hadlley 1999, pers. comm.). However, individual institutions offering this course are free to provide additional material and opportunities for this could be explored for local course providers. Excluding the lightkeepers, there is little at Race Rocks to indicate its status as a protected area, other than a sign at the dock on Great Race Rock, nor the type of behaviour that should be observed while there. The posting of more signs should be considered in addition to the continued distribution of information pamphlets at nearby marinas and access points.

Considerable infrastructure for public information and outreach already exists for Race Rocks. Pearson College maintains a comprehensive website and hosts a number of local school children at Race Rocks for education programs each year. Opportunities for expanding this program should be considered to include a wider range of students and other community groups with additional support from DFO and BC Parks. As mentioned previously, Pearson College is also seeking partnerships for the creation of a virtual Race Rocks education centre using internet and satellite technologies. While this initiative has considerable educational potential, it may also serve to heighten interest for visitation to the site, thus increasing the need for the firm establishment of measures to control such visitation.

5.6 Tour Operator and Staff Training

Aiello (1998) writes that “[w]ell informed staff with good communication skills are an essential component of successful tour operations in any setting” (p. 60). Furthermore, quality interpretation provides a competitive advantage and therefore economic incentive to operators in a high volume market such as the one at Victoria (Aiello 1998). In a study of an Australian reef tour company conducted by Aiello, customer feedback with respect to staff interpretation found that clients “enjoyed being able to ask any staff member questions about the environment, not just the few designated Naturalists” and that this indicated a “high level of professionalism” (Aiello 1998, p. 58). Furthermore, the study found that the teaching of interpretation skills was equally as important as biological and ecological content (Aiello 1998). Aiello concluded that while not all tour operator staff need to be experts in marine biology, highly professional marine tourist operations are maintained through all boat staff receiving “enough biological and interpretive training to be confident in sharing a sense of wonder, beauty and knowledge of the GBR with all customers, giving them a memorable ‘take home message’ (Aiello 1998, p. 60).

The present author had occasion to provide impromptu interpretation at Race Rocks aboard a whale watching vessel on a private charter (i.e. the vessel was not actively engaged in a commercial whale watching/wildlife viewing tour at the time). I was asked to provide information about the site as the naturalist present was new and unfamiliar with the area. Unfortunately, as I have no training in natural history, I was only able to impart details concerning the protected status of the ecological reserve and the pilot project. However, it was encouraging to find that passengers were extremely curious and enthusiastic for information regarding the local wildlife, particularly when they believed there to be someone present in possession of such knowledge. The experience reinforced the demand for, and importance of, the provision of quality interpretation, in addition to the need for naturalist training in local ecology and wildlife.

Currently there is one course available to tour operation staff in the whale watching industry in Victoria. This is run by the Marine Mammal Research Group (MMRG) in Victoria and consists of an eight week basic naturalist course supplemented by a lecture series which is updated every year. The course is run each spring and the material focuses on whales but also includes local ecology and conservation of marine species, in addition to techniques for interpretation and the fostering of a stewardship ethic among public audiences (Bates 1999, pers. comm.; The Whale Museum 1999). Topics in the lecture series change each year and present up-to-date information and research on various species. These are often attended by naturalists who have already taken the basic course.

The course is virtually mandatory among whale watching staff and companies will often pay for the training for new employees. Similarly, those with the training are more likely to find employment in the industry (Bates 1999, pers. comm.). The MMRG receives some funding from the WWOANW but relies entirely on the dedication and continued interest of the MMRG’s sole co-ordinator, Ron Bates. Means should be explored to secure the future availability of the program in addition to the possibility of licensing of the course to other groups, such as the WWOANW, in partnership with government and other relevant agencies. Staff from other tourist operations could also be encouraged to take the course.

While the requirement for permits for commercial activities in ecological reserves is already legislated in the BC Parks Act, its administration is all but non-existent for the commercial tourism industry. The rigorous application of a permit system could serve a number of important functions including the control of entry into an already highly competitive tourism market, the collection of data on visitor use, the collection of a nominal fee to assist in its administration, the assurance of industry-wide acknowledgement of regulations, and the application of requirements for minimum standards of operation in terms of behaviour and educational content. Such a system could also require environmental impact assessments for new activities and allow new proposals to be considered on a case by case basis.

5.8 Partnerships for Stewardship/Stakeholder and Community Participation

Wells and White (1995) write that “[w]here people are dependent on their adjacent marine resources for their livelihoods, the establishment of an MPA is likely to have a significant impact on their lives and, inevitably, results in a reaction from the community. The challenge to managers of MPAs is to channel this response into support for the project” (p. 63). One of the most important features of the pilot MPA project at Race Rocks, and indeed of MPAs around the world, is the cultivation of partnerships and the provision of opportunities for stakeholder consultation and input, in order to achieve this support. Indeed, the success of the proposed MPA at Race Rocks will hinge upon how effectively partnerships are established and upon open channels of communication between management and stakeholders.

Partnerships and stakeholder input generate support for MPAs, opportunities for research and education and go a long way towards ensuring that mutually-agreed upon regulations will be adhered to. This reduces the need for formal enforcement which is a major issue for MPA management. Marion and Rogers (1994) write that managers