Sunny Ashcroft

September 22, 2000

Laboratory: A Sealion Ethology

Aim:

To become familiar with the process of preparing an ethology, including observation over a period of time, proper techniques of observation, and analysis of data collected. Natural animal behavior of sealions will be studied using field observations, and patterns of behavior will try to be identified and quantified using an ethogram and time budget. An ethogram lists behaviors observed by the subject, while the time budget gives the percentage of time that the subject engaged in the behavior.1

Introduction

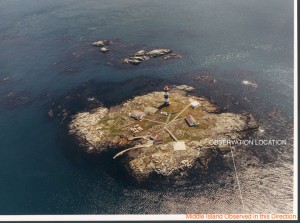

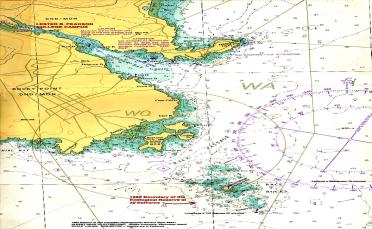

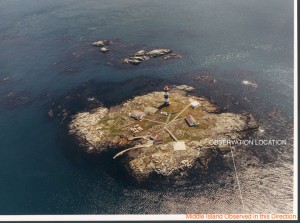

Data for this ethology was collected on Race Rocks, a rocky outcrop housing a lighthouse and several buildings, and now an ecological reserve, located in the Juan de Fuca Strait. Figure 1 shows the location at which the subjects were observed, with field binoculars, and the site of observation.

Figure 1: Photo of Race Rocks showing observation location and site of observation

The group of sea lions observed consisted of both species of sealion found at Race Rocks, California and Steller’s. The observations were taken over the period of one hour, with 6 minutes being allotted to each of the 10 sealions observed, 5 of the subjects being the darker and smaller Steller’s sealions, Eumetopias jubatus, and 5 of the subjects being the pale and larger California sealions, Zalophus californianus. Due to the distance that the observations were taking place, I was unable to identify the morphology of the sealions observed. This particular group of sealions was observed from 12:00pm to 1:00pm on September 15, 2000. The weather was fair, with sun and only sparse cloud cover, and a breeze.

Data Analysis

Part A: Sealion Ethogram

Grooming behavior

– scratching

intermediately looking around, observing

grooming (i.e. licking, smoothing self with tongue)

stretching

|

Observation

sitting up on fins

looking up at sky

looking around

|

Making noises

Sitting up and random noise making (i.e. non aggressive barking)

Socially aggressive

no extensive movement of body (excluding sitting up or posturing)

opened mouth aggression, may or not be making noise

aggressive posturing

|

Movement:aggressive, or because of antagonism

involves making noise (i.e. barking)

aggressive charging or chasing

movement away or towards an aggressor

being aggressive towards others

|

Movement:not aggressive

moving for better position on rock, or sleeping position |

Resting

laying down with intermediate head raising or barking

yawning

|

|

|

|

Part B: Sealion Time Budget

Number of 6 min. observation periods

|

10 |

%E. Movement:aggressive |

8% |

| Number of individuals observed |

10 |

% F. Movement:non aggressive |

24% |

Total minutes of observation

|

60 |

% G. Resting |

13% |

% A. Grooming behavior

|

29 |

|

|

| % B. Observation |

16 |

|

|

| % C. Making noises |

8% |

|

|

% D. Socially aggressive

|

2% |

|

|

|

Evaluation

According to Figure 2 it appears that most of a sealion’s time, in comparison with other behavioral categories identified, is spent grooming (29%). This is followed by non-aggressive movement (24%), and then by observation (16%) and resting (13%). Both at 8% of the observed hour are aggressive movement and making noises. The least part of the sealion’s hour, 2%, was spent in socially aggressive behavior. This data would suggest that at this particular hour of observation, from 12:00pm to 1:00pm, sealions perched on rocks can be said to spend their time at various activities, but that the majority of time is spent grooming, moving non-aggressively (for better resting position), and resting. This behavior can be attributed to the fair weather and amount of sunlight available at this time of the day.This data does not really relate to the energy requirements of the species as the sealions were not observed to be feeding or hunting on or for their food.2 In fact from the data gathered, it might be possible to postulate that the sealions, during that one hour period, did not require much energy at all since they were mostly at rest, and at activities related to their own well being that were not related to hunting or eating. Similarily the data collected also does not shed that much light on the adaptive strategy of the sealion.3 The data collected can be interpreted to say that sealions are adapted to lying and resting on the land, with such motor capabilities and lung capabilities as needed, away from possible predatory sources in the sea.

According to Figure 2 it appears that most of a sealion’s time, in comparison with other behavioral categories identified, is spent grooming (29%). This is followed by non-aggressive movement (24%), and then by observation (16%) and resting (13%). Both at 8% of the observed hour are aggressive movement and making noises. The least part of the sealion’s hour, 2%, was spent in socially aggressive behavior. This data would suggest that at this particular hour of observation, from 12:00pm to 1:00pm, sealions perched on rocks can be said to spend their time at various activities, but that the majority of time is spent grooming, moving non-aggressively (for better resting position), and resting. This behavior can be attributed to the fair weather and amount of sunlight available at this time of the day.This data does not really relate to the energy requirements of the species as the sealions were not observed to be feeding or hunting on or for their food.2 In fact from the data gathered, it might be possible to postulate that the sealions, during that one hour period, did not require much energy at all since they were mostly at rest, and at activities related to their own well being that were not related to hunting or eating. Similarily the data collected also does not shed that much light on the adaptive strategy of the sealion.3 The data collected can be interpreted to say that sealions are adapted to lying and resting on the land, with such motor capabilities and lung capabilities as needed, away from possible predatory sources in the sea.

Several sources of error can be identified in this particular experiment. The first and perhaps most important is the failure of the group to return to Race Rocks at a similar time of day, during the same part of the year, to do another hour of observation of the sealions. This data would have been very beneficial in the compilation of both the time budget and the ethogram and would have made our observations more accurate. The observations, had they been taken during two different intervals, should be made at relatively the same time of day and year to keep the results as accurate as possible, as to relate what that species is doing at that particular point in time, during that time of day.

The sealions observed by the group were of different species. This fact is very interesting. Our observations can then be said to represent the behavior of “sealions” in general, but is not very species specific. To be entirely accurate and precise only one of the species should have been observed for the hour. In that manner our observations could be said to accurately depict the behavior of such and such species at such and such time in the day.

The groups method of recording data is judged to have been fairly good. In a group of two, the 6 min periods of time were alternated between us, and the one partner who was not looking through the field glasses at the subject was recording and timing the observations of the other. This proved to be a fairly efficient and effective manner of recording data. A source of error could be attributed to the amount of time taken for the next observer to pick up the field glasses and locate the new subject of observation. To improve upon this it is suggested that only one person take the observations the entire hour, and the other partner record everything observed. This would eliminate the time gap, but it wouldn’t be very much fun .

The distance at which our observations were taken did not allow the group to identify between the males and females of both species. This is unfortunate and would have added to our data. If we were able to the group should have pre-determined that half of the hour would be given to females of the species, and half of the hour to males. This would have allowed for more accurate and impartial data. The fact that the group was unable to determine the sex of the sealions also gives rise to the question, what other details did we miss out on because of the distance of our observations? If possible, the observations should have been made at a distance where important details could be observed, but the observers would have to keep in mind that they should disturb the natural environment as little as possible. As it was, our distance did not allow for disturbance of the sealions or their environment.

The temperature, wind direction, water temperature, and other related physical statistics about the area of observation were not noted down at the time of observation. The absence of this data is of particular importance when analyzing the reason for the behavior of the sealions being what it is, and why so much time was spent on a particular activity. For instance, I have postulated above that the sealions spent so much time grooming, resting, and moving to get into a better resting position, because the weather was so fair and sunlight in abundance. More accurate observations of temperature and the weather would have assisted in this analysis.

Our group’s method of observing a group of sealions at a particular physical location, with 6 min on each individual, is judged to have been a fairly good one. Our group moved from the individuals in the left of the group to the individuals to the right of the group, one sealion after another, spending 6 min of observation time on each individual. This resulted in impartiality and our data being a representation of the entire group of sealions at that particular hour. The data collected can only be said to represent the behavior at that particular location though:what about those sealions in the water, what are they doing? As this data was not gathered, our observations cannot be said to truly depict an hour in the life of a sealion, only an hour in the life of those sealions that were resting on that rock at that time.

As for the compilation of the data collected, the most objective descriptions can be said to be the sub-points in the categories A through G. The categories themselves, the category titles, and the grouping of the sub-points into their respective categories, can be said to be more subjective. My ability to judge what behavior belongs in which category, for example in the grooming category, which includes both elements of observation and the subject licking itself, I established that grooming behavior appeared to include periods of looking up from one’s grooming and observing one’s surroundings. This is my own personal interpretation, and while it may not be correct, is what I correlate with what I have observed. This makes such categories subjective in manner. Others may not necessarily categorize what I may categorize as a certain behavior the same way. As well my personal method of making an ethogram is quite interesting. I have clearly identified seven behavioral categories that include specific behavioral actions. These are my interpretations of what my group observed. In this way the ethogram itself can be said to be subjective.

Overall the laboratory, and results obtained, are judged to have been adequate for the aim proposed.

Resources“Race Rocks Website https://www.racerocks.ca accessed September 21, 2000

Appendix A,

“Ethology Laboratory“, prepared by Matt Rise

“Sealion Field guide”, http://www.lifestories.com/Spring99/field-guide/seal-field-guide.htm, accessed September 21, 2000

1. sentence adapted from Introduction in “Ethology Laboratory” handout

2. referring to question 7 in “Ethology Laboratory” handout

3. referring to question 8 in “Ethology Laboratory” handout

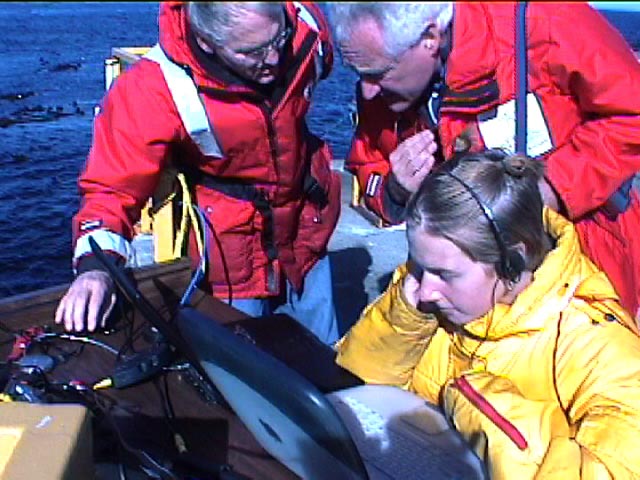

September 11, 2001 We met this afternoon for the first session of the racerocks.com activity at Lester Pearson College. A tragic day for all of us as events unfold in the US. After a discussion of how the racerocks.com program has developed over the past few years, and projections as to where we may take it from here, we ran a short sample webcast from the biology lab. We were able to show the eight new first year students in the activity the process involved in a webcast.

September 11, 2001 We met this afternoon for the first session of the racerocks.com activity at Lester Pearson College. A tragic day for all of us as events unfold in the US. After a discussion of how the racerocks.com program has developed over the past few years, and projections as to where we may take it from here, we ran a short sample webcast from the biology lab. We were able to show the eight new first year students in the activity the process involved in a webcast.

s including Pearson College and The Canadian Coastguard. The environmental integrity of the site is often jeopardised to bring diesel fuel to the site and the noise pollution on the site due to the diesel generators is significant. IESVic has stepped forward to evaluate the potential of renewable energy sources on-site to power a sustainable energy system. A preliminary study was performed as an innovative graduate course at the University of Victoria that exposed students to sustainable energy system design. Our conclusion is that with Tidal currents of up to 3.7 m/s, average winds of 21.6 km/h and large amounts of solar insolation, there are ample renewable resources available on the site to develop a sustainable integrated energy system capable of providing reliable power for the site. Race Rocks is therefore ideally

s including Pearson College and The Canadian Coastguard. The environmental integrity of the site is often jeopardised to bring diesel fuel to the site and the noise pollution on the site due to the diesel generators is significant. IESVic has stepped forward to evaluate the potential of renewable energy sources on-site to power a sustainable energy system. A preliminary study was performed as an innovative graduate course at the University of Victoria that exposed students to sustainable energy system design. Our conclusion is that with Tidal currents of up to 3.7 m/s, average winds of 21.6 km/h and large amounts of solar insolation, there are ample renewable resources available on the site to develop a sustainable integrated energy system capable of providing reliable power for the site. Race Rocks is therefore ideally

According to Figure 2 it appears that most of a sealion’s time, in comparison with other behavioral categories identified, is spent grooming (29%). This is followed by non-aggressive movement (24%), and then by observation (16%) and resting (13%). Both at 8% of the observed hour are aggressive movement and making noises. The least part of the sealion’s hour, 2%, was spent in socially aggressive behavior. This data would suggest that at this particular hour of observation, from 12:00pm to 1:00pm, sealions perched on rocks can be said to spend their time at various activities, but that the majority of time is spent grooming, moving non-aggressively (for better resting position), and resting. This behavior can be attributed to the fair weather and amount of sunlight available at this time of the day.This data does not really relate to the energy requirements of the species as the sealions were not observed to be feeding or hunting on or for their food.2 In fact from the data gathered, it might be possible to postulate that the sealions, during that one hour period, did not require much energy at all since they were mostly at rest, and at activities related to their own well being that were not related to hunting or eating. Similarily the data collected also does not shed that much light on the adaptive strategy of the sealion.3 The data collected can be interpreted to say that sealions are adapted to lying and resting on the land, with such motor capabilities and lung capabilities as needed, away from possible predatory sources in the sea.

According to Figure 2 it appears that most of a sealion’s time, in comparison with other behavioral categories identified, is spent grooming (29%). This is followed by non-aggressive movement (24%), and then by observation (16%) and resting (13%). Both at 8% of the observed hour are aggressive movement and making noises. The least part of the sealion’s hour, 2%, was spent in socially aggressive behavior. This data would suggest that at this particular hour of observation, from 12:00pm to 1:00pm, sealions perched on rocks can be said to spend their time at various activities, but that the majority of time is spent grooming, moving non-aggressively (for better resting position), and resting. This behavior can be attributed to the fair weather and amount of sunlight available at this time of the day.This data does not really relate to the energy requirements of the species as the sealions were not observed to be feeding or hunting on or for their food.2 In fact from the data gathered, it might be possible to postulate that the sealions, during that one hour period, did not require much energy at all since they were mostly at rest, and at activities related to their own well being that were not related to hunting or eating. Similarily the data collected also does not shed that much light on the adaptive strategy of the sealion.3 The data collected can be interpreted to say that sealions are adapted to lying and resting on the land, with such motor capabilities and lung capabilities as needed, away from possible predatory sources in the sea.