Trevor aAnderson, Air Force Veteran, lighthouse keeper, offshore sailor. an article in Pacific Yachting magazine of December.

See the pdf here: Anderson

COASTAL CHARACTERS BY MARIANNE SCOTT

TREVOR ANDERSON

Air Force veteran, lighthouse keeper, offshore sailor

Only a few Second World War veterans remain with us today—Trevor Anderson is one of them. At age 99, he vividly recalls his war experiences, serving as a Morse code radio operator and doubling as gunner. “When the war broke out in 1939, I tried to enlist and finally made it in 1941,” he told me. He received his radio operator and gunner training in Calgary and Saskatchewan and eventually made it to England. “I was required to signal 16 words a minute in Morse code,” he recalls,“but it bumped up to 20 words in the UK. I’ve built a life-sized model Morse communication setup in the basement.”

After time in Scotland, he and 700 others boarded the SS Pasteur and spent two months sailing to the Cape of Good Hope, then to Aden.“Somebody goofed, ”Trevor says.“We were supposed to go to Burma but were dumped in Cairo.We had no notion we were going to North Africa.” He was attached to the British Royal Air Force with about 100 other Canadians, a few Australians and New Zealanders, but was scuttled all around the fighting between the Allies under Bernard Montgomery and the Germans under Erwin Rommel. “We moved continually,” he says.“It was a shemozzle.Tents, dust, sand, fleas and crickets. They assigned me to the American forces, who didn’t use Morse code. No keys in the planes to start with.Very insecure.” “The Americans wanted to fly at night,” he continued.“But their exhaust trails lit up like Vegas. So they changed their tactics.”

He spent 18 months in the desert, variously stationed in Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and later, Sicily. Crouched in a small gun turret attached to the belly of American B-25 bombers, he handled two 50-calibre machine guns and the Morse code key.

On his fourth mission, January 2, 1943, his plane was hit and ditched in the Mediterranean while he signaled their location. Somehow, he escaped from the belly turret through a dinner plate-sized window and survived with six others in a dinghy for 30 hours.

Altogether, Trevor flew 55 missions— while the usual limit for gunners was 25-30 missions. During his 55th bombing run, an inexperienced colonel wanting flight pay missed the Italian target twice and then got lost. Trevor’s Morse code requests for help got them back to Sicily. The next morning, he visited the colonel. “Sir,” he said, “I’ve had enough.” (He tells me this story in his modest, understated way. Today, he’d be called a hero.) After flying to Cairo, he found the Canadians were clueless about what to do with him, but they released him from the combat area; Trevor went home to Victoria via West Africa, Brazil, Curacao, Miami and Ottawa.

WHILE IN NORTH Africa, Trevor, like all military men, thirsted for mail from home. Among the letter writers was Florence, aka Flo. “Our fathers were part of a small lending circle in Victoria and she wrote me regularly,” says Trevor, “mind you, it wasn’t romantic. But sometime during my desert sojourn, I asked her to marry me. She said yes.”

They married in 1944 after Flo finished her Victoria College studies; the marriage lasted 73 years. “When Hitler was defeated, we were released and every soldier was looking for work,” he recalled. “So after a few months, I went back into the Air Force and was posted in the Queen Charlotte Islands and Ottawa, teaching flight simulation for pilots.” Later, he and his growing family of two boys and two girls were stationed around Canada while Trevor flew all over the world in Dakotas and North Stars operating the radio while supplying the bases along the Alaska Highway and transporting dignitaries. He also served as radar fighter controller on several bases, retiring from the Air Force in 1960.

THE NEXT PHASES of Trevor’s life revolved around the sea. In 1961, he took the job of assistant lighthouse keeper and he, Flo and their four kids relocated to Lennard Island, near Tofino. Their government-issued home was on the verge of dereliction, cold and without running water. Electricity came on at night when the lighthouse operated and the Andersons turned night into day, with the children studying and Flo doing her household chores. In her autobiography Lighthouse Chronicles, Flo explained the senior keeper was a vicious drunk. Perhaps because Trevor had trained for lighthouse keeper duties, he’d become a threat to those without formal training; suddenly, the Department of Transport informed him he was fired. The noxious senior keeper had written a batch of letters reporting Trevor performed his duties badly.

Trevor journeyed to Victoria to protest his dismissal. After a lengthy investigation, he was reinstated, then promoted and appointed senior keeper at Barrett Rock. The family became rock hoppers, relocating to McInnes Island in Milbanke Sound, then to stormy Green Island, the northernmost-staffed lighthouse in Canada. They called it an “igloo” as the incessant tempests created rotund— and treacherous—ice pillows on the beaches. The Andersons lived through two ice-sprayed winters until July 1966, when they transferred to Race Rocks, which became a true home. They stayed 16 years.

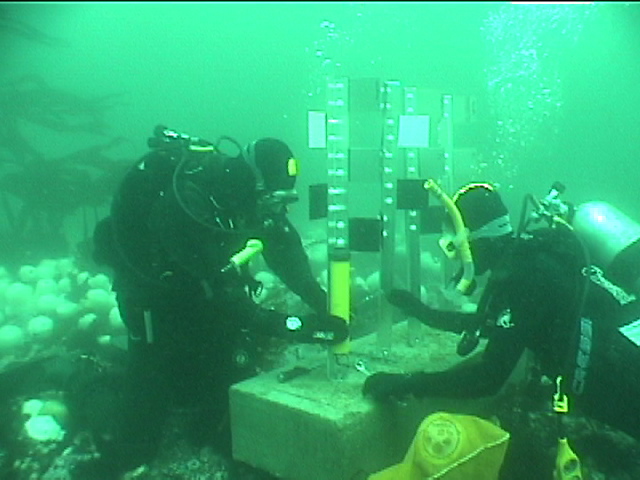

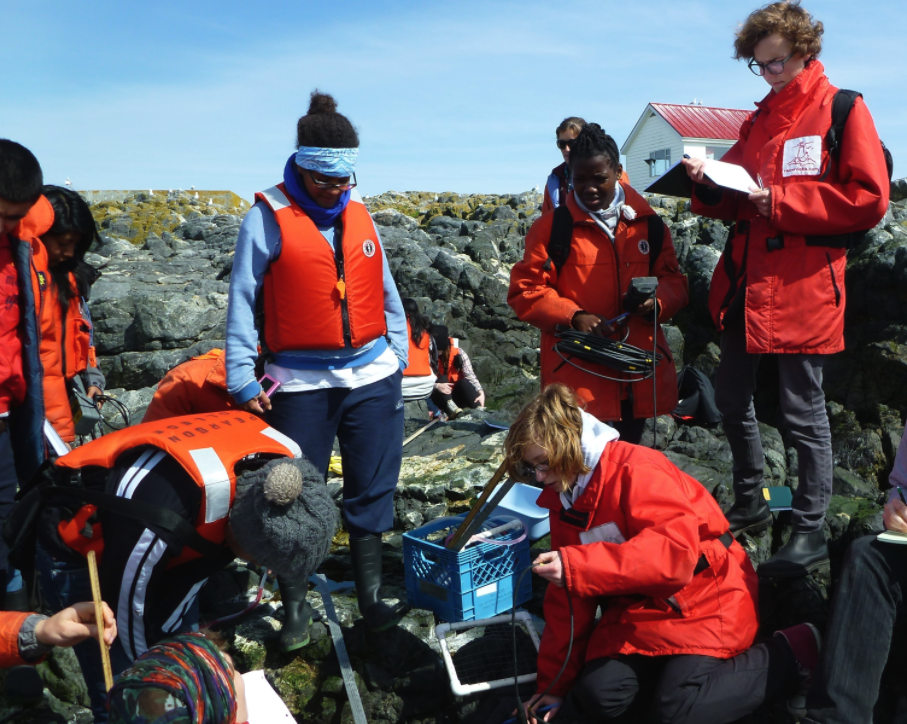

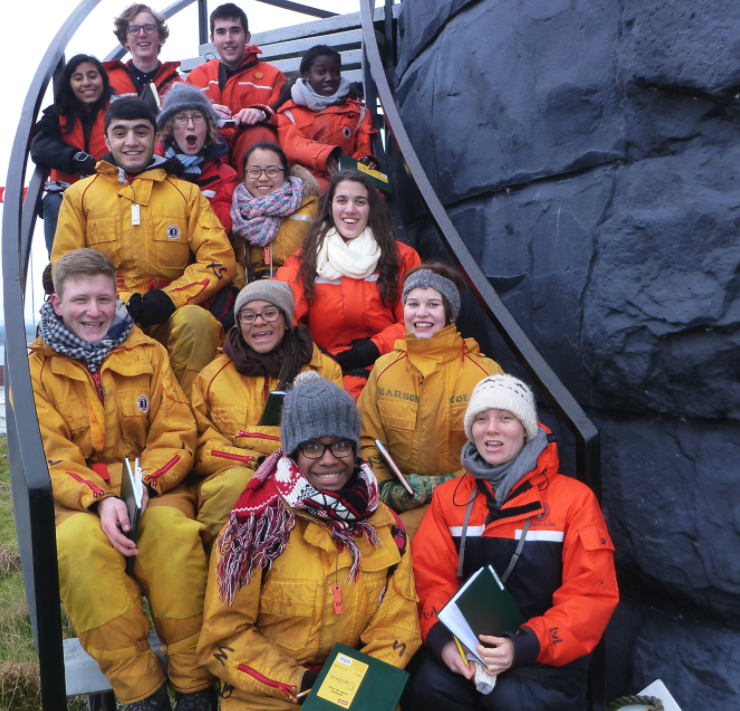

Besides staffing the lights, the Andersons worked with Pearson College students and their marine biology teacher Garry Fletcher (featured in PY October 2019) to investigate the nine Race Rocks isles, their unique ecology, the surrounding high-current waters and various forms of alternative electricity production. They helped Garry to establish Race Rocks as an Ecological Reserve—areas set aside to preserve exceptional natural features. At some time, Trev and Flo decided they needed a sailboat and vowed to build one themselves, despite their lack of boatbuilding knowledge and skills. They spent much time pouring over Chappelle’s Boatbuilding and reading books penned by such sailors as the Hiscocks. They also met renowned boat designer Bill Garden. Over seven years, they built their 56-foot ketch (42 feet without bowsprit and davits), Wawa the Wayward Goose, launching her in 1982. “I knew I’d figure out all the intricacies eventually,” Trev says. “Bill Garden was enthralled.” They learned sailing by doing, first cruising the Gulf Islands, and then circumnavigating Vancouver Island. In July 1985, they headed offshore to Hawaii, New Zealand, Tonga, Samoa, Fanning Island and Pago Pago. After returning to Victoria in 1987, they continued to live on Wawa for another eight years before returning to life on solid land.

Flo died in 2017, at 93 years of age. Having had her companionship for nearly three-quarters of a century, Trevor misses her enormously. “Being alone is hard,” he says. He continues to live in the 100-plus year-old house in Victoria’s James Bay (Flo’s parents once owned it). Although he spent more than 20 years in military service, Canada denied him a pension, as “the service wasn’t continuous.” Consequently, he doesn’t have much use for Remembrance Days or other veteran recognitions.

How does one live until 99 and still be upright? “My philosophy of life is to take things as they come,” Trevor says. “Don’t do what you can’t do. I don’t think much about it, I’m just here. I’ve survived an airplane crash, a car crash and a mangled foot. I don’t drink, quit smoking more than 50 years ago. I just continue to live, day after day.” �